State Violence in Guatemala, 1960-1996: a Quantitative Reflection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guatemala Timeline

Guatemala Timeline 1954: The U.S. backs a coup led by Carlos Castillo Armas against Guatemala's president, Jacobo Arbenz, which halts land reforms. Castillo Armas becomes President and takes away voting rights for illiterate Guatemalans. 1957: On July 26, President Armas is killed. 1960: The violent Guatemalan Civil War begins between the government's army and left-wing groups. Thousands of murders, rapes, tortures, and forced disappearances were executed by the Government toward the indigenous peoples. 1971: 12,000 students of the Universidad de San Carlos protest the soaring rate of violent crime. 1980: Maya leaders go to the Spanish Embassy in Guatemala to protest the numerous disappearances and assassinations by the State and to ask that the army be removed from their department, El Quiché. Security forces respond by burning the Embassy, which results in 37 deaths. 1982: Under President/Dictator Ríos Mont, the Scorched Earth policy targeting indigenous groups goes into effect. Over 626 indigenous villages are attacked. The massacre of the Ixil people and the Dos Erres Massacre are two of the most severe genocides during this time. 1985: Guatemala's Constitution includes three articles protecting the indigenous. Article 66 promotes their daily life, including their dress, language, and traditions. Article 67 protects indigenous land, and Article 68 declares that the State will give land to indigenous communities who need it for their development. 1985: The Academy of Mayan Languages of Guatemala (ALMG), which promotes and advocates for the use of the twenty-two Mayan languages in the public and private spheres, is recognized as an autonomous institution funded by the government. -

International Service Learning in IS Programs: the Next Phase

Information Systems Education Journal (ISEDJ) 16 (4) ISSN: 1545-679X August 2018 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ International Service Learning in IS Programs: The Next Phase – An Implementation Experience Kiku Jones [email protected] Wendy Ceccucci [email protected] Computer Information Systems Quinnipiac University Hamden, CT 06401, USA Abstract Information systems programs have offered students opportunities for service learning in their curriculum through elective courses and through capstone courses. However, even though there have been numerous research studies showing the benefits of international service learning experiences, information systems programs have not yet developed these in their curriculum on a large scale. This paper provides an account of an implementation of an international service learning experience through an information systems project management course. Students worked with a middle school in Guatemala to successfully deliver a sustainable website. The course is described using a modified service learning framework. The framework consists of preparation, action, reflection, evaluation, and share. The paper also provides challenges and lessons learned. This modified framework and challenges and lessons learned can be used by other programs to structure their own international service learning experience. Keywords: Service learning, international experience, project management, Information Systems Curriculum 1. INTRODUCTION -

Relación Comercial Guatemala – Panamá

Viceministerio de Integración y Comercio Exterior Dirección de Análisis Económico 03 de julio de 2018 Relación Comercial Guatemala – Panamá Indicadores Macroeconómicos de Panamá y Guatemala Año 2017* PANAMÁ GUATEMALA Descripción Población 4,034,119 16,924,190 PIB TOTAL (US$ US$55,187.7 millones US$75,589.6 millones PIB per Cápita (US$) US$13,680.2 US$4,466.4 Tasa de crecimiento PIB 5.5% 2.8% agricultura: 2.7% agricultura: 13.2% Composición PIB por sector industria: 28.1% industria: 23.6% servicios: 69.2% servicios: 63.2% Remesas US$502.2 millones US$8,192.2 millones Deuda pública 38.8% 23.9% del PIB Inflación 1.6% 5.6% Inversiones (Formación de 42.8% 12.5% capital) *cifras preliminares sujetas a cambios, excepto los datos económicos de Panamá que se encuentran al 2016 Fuente: Banco de Guatemala, Banco Mundial, Cia Factbook, Trademap 1 Viceministerio de Integración y Comercio Exterior Dirección de Análisis Económico 03 de julio de 2018 Indicadores Macroeconómicos de Panamá y Guatemala Año 2017* PANAMÁ GUATEMALA Descripción Exportaciones (US$) US$5,087.1 millones US$11,001.5 millones Participación n/a 15.9% exportaciones/PIB Ecuador (17.5%), Estados Unidos de América Japón (16.2%), (33.9%), Guatemala (10.9%), El Salvador (11.1%), Socios comerciales (EXP) Estados Unidos de Honduras (8.8%), América (9.0%), Nicaragua (5.1%), Países Bajos (6.5%) México (4.6%) Importaciones (US$) US$32,233.5 US$18,388.8 millones Participación n/a 26.5% importaciones/PIB China (17.8%), Estados Unidos de América Estados Unidos de (39.8%), América (17.3%), China -

Central America (Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua): Patterns of Human Rights Violations

writenet is a network of researchers and writers on human rights, forced migration, ethnic and political conflict WRITENET writenet is the resource base of practical management (uk) independent analysis e-mail: [email protected] CENTRAL AMERICA (GUATEMALA, EL SALVADOR, HONDURAS, NICARAGUA): PATTERNS OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS A Writenet Report by Beatriz Manz (University of California, Berkeley) commissioned by United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Status Determination and Protection Information Section (DIPS) August 2008 Caveat: Writenet papers are prepared mainly on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment. All sources are cited. The papers are not, and do not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. The views expressed in the paper are those of the author and are not necessarily those of Writenet or UNHCR. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms ................................................................................................... i Executive Summary ................................................................................ iii 1 Introduction........................................................................................1 1.1 Regional Historical Background ................................................................1 1.2 Regional Contemporary Background........................................................2 1.3 Contextualized Regional Gang Violence....................................................4 -

Faqs: Health, Safety and Travel During COVID-19 Response in Guatemala Table of Contents

FAQs: Health, Safety and Travel during COVID-19 Response in Guatemala Table of Contents General Information about the situation in Guatemala during the COVID-19 crisis .......................2 Are all borders and airports closed in Guatemala? ............................................................................................ 2 Should I try to cross into Mexico and fly to U.S. from there? .......................................................................... 2 Is a Curfew in effect in Guatemala? If so, what are the rules? ......................................................................... 3 Can I travel by land within Guatemala? ............................................................................................................ 3 Can I travel by Air within Guatemala? .............................................................................................................. 3 Where can I find all alerts published by the U.S. Embassy in Guatemala related to the COVID-19 crisis? . 3 Where can I find health information about COVID-19?.................................................................................. 4 If I go back to the U.S. will I be quarantined? ................................................................................................... 4 Information about air travel options not coordinated by the Department of State ...........................4 Information about Charter Flights organized by the Department of State .......................................4 Is the U.S. Embassy organizing -

Best Practices for Working with Interpreters

VERA NETWORK RESOURCE BEST PRACTICES FOR WORKING WITH INTERPRETERS Vera Institute of Justice ● Unaccompanied Children Program ● October 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ......................................................................................................................................1 Guidance for Working with Interpreters .............................................................................................2 What is Interpreting? ................................................................................................................................ 2 Assessing the Child’s Language Proficiency .............................................................................................. 2 The Benefits of Having Bilingual Staff ....................................................................................................... 2 Deciding on the Mode of Interpretation: Telephonic or In-Person? ........................................................ 3 Before the Session .................................................................................................................................... 3 During the Session .................................................................................................................................... 4 After the Session ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Appendix A: Indigenous Languages Spoken in Central America ............................................................6 -

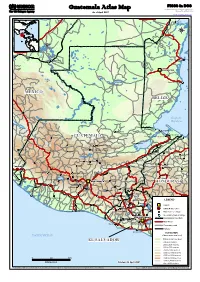

Guatemala Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services As of April 2007 Email : [email protected]

FICSS in DOS Guatemala Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services As of April 2007 Email : [email protected] ((( Corozal Guatemala_Atlas_A3PC.WOR Balancan !! !! !! !! Tenosique Belize City !! BELMOPANBELMOPAN Stann Creek Town !! MEXICOMEXICO BELIZEBELIZE !! Golfo de Honduras San Juan ((( !! Lívingston !! El Achiotal !! Puerto Barrios GUATEMALAGUATEMALA Puerto Santo Tomás de Castilla ((( ((( ((( Soloma ((( Cuyamel Cobán ((( El Estor ((( ((( Chajul ((( !! ((( San Pedro Carchá ((( Morales !! Motozintla Huehuetenango !! San Cristóbal Verapaz ((( Cunen ((( ((( !! Macuelizo ((( ((( Los Amates((( Petoa ((( Cubulco Salamá Trinidad ((( ((( !! Gualán ((( !! !! ((( !! ((( San Sebastián ((( San Jerónimo ((( Jesus Maria La Agua ((( !! Rabinal ((( Protección ((( Joyabaj TapachulaTapachula Totonicapán ((( Zacapa !! Naranjito ((( ((( !! Tapachula ((( ((( Santa Bárbara ((( Quezaltenango !! Dulce Nombre ((( !! San José Poaquil !! Chiquimula !! !! Sololá !! Santa Rosa !! Comalapa ((( Patzún !! Santiago Atitlán !! Tecun Uman !! Chimaltenango GUATEMALAGUATEMALA !! Jalapa HONDURASHONDURAS Mazatenango HONDURASHONDURAS Antigua ((( !! Esquipulas !! !! Retalhuleu ((( !! ((( Ciudad Vieja ((( Monjas Alotenango ((( Nueva Ocotepeque !! ((( Santa Catarina Mita Amatitlán ((( ((( Patulul ((( Ayarza Río Bravo ((( ((( Metapán !! !! Escuintla ((( !! ((( !! Jutiapa((( ((( !! Champerico ((( !! Cuilapa !! Asunción Mita ((( Yamarang Pueblo Nuevo Tiquisate ((( Erandique Yupiltepeque ((( ((( Atescatempa Nueva Concepción LEGEND -

How Local Institutions Emerge from Civil War Regina Bateson Assistant Professor

How Local Institutions Emerge from Civil War Regina Bateson Assistant Professor Department of Political Science MIT Oct. 2, 2015 The field research for this paper was supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, Yale University, and the Tinker Foundation. I gratefully acknowledge research support from tHe Universidad del Valle de Guatemala wHile in tHe field. At MIT, Meghan O’Dell provided superb research assistance. Please send comments and questions to [email protected] . ABSTRACT: Civil wars are typically understood as destructive, leaving poor economic performance, damaged pHysical infrastructure, and reduced Human capital in their wake. But civil wars are also constructive, producing new local institutions that can persist into the postwar period. In this paper, I use qualitative evidence from Guatemala to demonstrate tHat even tHe most devastating conflicts can spawn durable local institutions. Specifically, I focus on the civil patrols, which were government-sponsored local militias during tHe Guatemalan civil war. AltHougH tHe Peace Accords of 1996 required tHe civil patrols to demobilize, I sHow tHat more nearly 20 years later, tHey are still patrolling, functioning as security patrols in tHeir communities today. After considering alternative explanations, I use Historical documents and ricH, etHnograpHic evidence to draw causal links between tHe wartime civil patrols and tHe present-day security patrols. These findings begin to fill a gaping hole in the literature on the civil wars, whicH—until now—has largely ignored the local institutional consequences of conflict. _________________________________________________________________________________________________ The study of civil wars is riven with intractable debates. When, where, and why are civil wars most likely (e.g. -

Cooperative Agreement on Human Settlements and Natural Resource Systems Analysis

COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT ON HUMAN SETTLEMENTS AND NATURAL RESOURCE SYSTEMS ANALYSIS CENTRAL PLACE SYSTEMS IN GUATEMALA: THE FINDINGS OF THE INSTITUTO DE FOMENTO MUNICIPAL (A PRECIS AND TRANSLATION) RICHARD W. WILKIE ARMIN K. LUDWIG University of Massachusetts-Amherst Rural Marketing Centers Working Gro'p Clark University/Institute for Development Anthropology Cooperative Agreemeat (USAID) Clark University Institute for Development Anthropology International Development Program Suite 302, P.O. Box 818 950 Main Street 99 Collier Street Worcester, MA 01610 Binghamton, NY 13902 CENTRAL PLACE SYSTEMS IN GUATEMALA: THE FINDINGS OF THE INSTITUTO DE FOMENTO MUNICIPAL (A PRECIS AND TRANSLATION) RICHARD W. WILKIE ARMIN K. LUDWIG Univer ity of Massachusetts-Amherst Rural Marketing Centers Working Group Clark University/Institute for Development Anthropology Cooperative Agreement (USAID) August 1983 THE ORGANIZATION OF SPACE IN THE CENTRAL BELT OF GUATEMALA (ORGANIZACION DEL ESPACIO EN LA FRANJA CENTRAL DE LA REPUBLICA DE GUATEMALA) Juan Francisco Leal R., Coordinator of the Study Secretaria General del Consejo Nacional de Planificacion Economica (SGCNPE) and Agencia Para el Desarrollo Internacional (AID) Instituto de Fomento Municipal (INFOM) Programa: Estudios Integrados de las Areas Rurales (EIAR) Guatemala, Octubre 1981 Introduction In 1981 the Guatemalan Institute for Municipal Development (Instituto de Fomento Municipal-INFOM) under its program of Integrated Studies of Rural Areas (Est6dios Integrados de las Areas Rurales-EIAR) completed the work entitled Organizacion del Espcio en la Franja Centrol de la Republica de Guatemala (The Organization of Space in the Central Belt of Guatemala). This work had its origins in an agreement between the government of Guatemala, represented by the General Secretariat of the National Council for Economic Planning, and the government of the United States through its Agency for International Development. -

Maize Genetic Resources of Highland Guatemala in Space and Time

Seeds, hands, and lands Maize genetic resources of highland Guatemala in space and time Promotoren Prof. dr. P. Richards Hoogleraar Technologie en Agrarische Ontwikkeling Wageningen Universiteit Prof. dr. ir. A.K. Bregt Hoogleraar Geo-informatiekunde Wageningen Universiteit Co-promotoren Dr. ir. S. de Bruin Universitair docent, Centrum voor Geo-Informatie Wageningen Universiteit Dr. ir. H. Maat Universitair docent, leerstoelgroep Technologie en Agrarische Ontwikkeling Wageningen Universiteit Promotiecommissie Dr. E.F. Fischer (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA) Dr. ir. Th.J.L. van Hintum (Centrum voor Genetische Bronnen Nederland, Wageningen) Prof. dr. L.E. Visser (Wageningen Universiteit) Prof. dr. K.S. Zimmerer (University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA) Dit onderzoek is uitgevoerd binnen CERES Research School for Resource Studies for Development en C.T. de Wit Graduate School for Production Ecology and Resource Conservation. Seeds, hands, and lands Maize genetic resources of highland Guatemala in space and time Jacob van Etten Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor op gezag van de rector magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit, prof. dr. M.J. Kropff, in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 11 oktober 2006 des namiddags te vier uur in de Aula © Jacob van Etten, except Chapter 2 Keywords: plant genetic resources, Guatemala, maize ISBN: 90-8504-485-5 Cover design: Marisa Rappard For Laura and Hanna Acknowledgments This work was financially supported by Wageningen University and Research Centre through the CERES Research School for Resource Studies for Human Development and through the C.T. de Wit Graduate School for Production Ecology and Resource Conservation. I am grateful for having such good supervisors, who advised me on crucial points but also allowed me much freedom. -

Recommended Reading: Latin America

Recommended Reading: Latin America In our busy lives, it is hard to carve out time to read. Yet, if you are able to invest the time to read about the region where you travel, it pays off by deepening the significance of your travel seminar experience. We have compiled the following selection of book titles for you to help you get started. Many titles are staff recommendations. Titles are organized by the topics listed below. Happy reading! Bolivia Latin American Current Affairs Cuba Latin American History El Salvador Globalization Guatemala Indigenous Americans Honduras Religion / Spirituality Mexico U.S.-Mexico Border Nicaragua U.S. Policy in Central & Latin America Women & Feminism Film Literature Testimonials Latin American Current Affairs Aid, Power and Privatization: The Politics of Telecommunication Reform in Central America by Benedicte Bull Northampton, MA.: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2005; ISBN: 1845421744. A comparative study of privatization and reform of telecommunications in Costa Rica, Guatemala and Honduras. The focus is on political and institutional capacity to conduct the reforms, and the role of the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) in supporting the processes at various stages. Gaviotas: A Village to Reinvent the World by Alan Weisman, Chelsea Green Publishing Company, 1998. Journalist Weisman tells the story of a remarkable and diverse group of individuals (engineers, biologists, botanists, agriculturists, sociologists, musicians, artists, doctors, teachers, and students) who helped a Colombian village evolve into a very real, socially viable, and self-sufficient community for the future. Latin American Popular Culture: An Introduction, edited by William Beezley and Linda Curcio-Nagy, Scholarly Resources, 2000. -

Chapter 6 Final

Table of Contents Chapter 6: Modifications to the Early Style Text After 1870 ................................................................ 2 6.1. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 2 6.2. Tecpán Lineage ............................................................................................................... 3 6.3. Cunén Lineage ................................................................................................................ 6 6.4. Cantel Lineage ................................................................................................................ 8 6.4.1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 8 6.4.2. Prologue (Bode’s Ajitz Variant) ................................................................................ 10 6.4.3. Azteca/Lacandón scene .......................................................................................... 11 6.4.4. PART I. .................................................................................................................... 11 6.4.5. Part II ...................................................................................................................... 18 6.4.6. Part III ..................................................................................................................... 23 6.4.7. Part IV ....................................................................................................................