Modern Painting, Its Tendency and Meaning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heather Buckner Vitaglione Mlitt Thesis

P. SIGNAC'S “D'EUGÈNE DELACROIX AU NÉO-IMPRESSIONISME” : A TRANSLATION AND COMMENTARY Heather Buckner Vitaglione A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of MLitt at the University of St Andrews 1985 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/13241 This item is protected by original copyright P.Signac's "D'Bugtne Delacroix au n6o-impressionnisme ": a translation and commentary. M.Litt Dissertation University or St Andrews Department or Art History 1985 Heather Buckner Vitaglione I, Heather Buckner Vitaglione, hereby declare that this dissertation has been composed solely by myself and that it has not been accepted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a candidate for the degree of M.Litt. as of October 1983. Access to this dissertation in the University Library shall be governed by a~y regulations approved by that body. It t certify that the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations have been fulfilled. TABLE---.---- OF CONTENTS._-- PREFACE. • • i GLOSSARY • • 1 COLOUR CHART. • • 3 INTRODUCTION • • • • 5 Footnotes to Introduction • • 57 TRANSLATION of Paul Signac's D'Eug~ne Delac roix au n~o-impressionnisme • T1 Chapter 1 DOCUMENTS • • • • • T4 Chapter 2 THE INFLUBNCB OF----- DELACROIX • • • • • T26 Chapter 3 CONTRIBUTION OF THE IMPRESSIONISTS • T45 Chapter 4 CONTRIBUTION OF THB NEO-IMPRBSSIONISTS • T55 Chapter 5 THB DIVIDED TOUCH • • T68 Chapter 6 SUMMARY OF THE THRBE CONTRIBUTIONS • T80 Chapter 7 EVIDENCE • . • • • • • T82 Chapter 8 THE EDUCATION OF THB BYE • • • • • 'I94 FOOTNOTES TO TRANSLATION • • • • T108 BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • • • T151 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Plate 1. -

TEL AVIV PANTONE 425U Gris PANTONE 653C Bleu Bleu PANTONE 653 C

ART MODERNE ET CONTEMPORAIN TRIPLEX PARIS - NEW YORK TEL AVIV Bleu PANTONE 653 C Gris PANTONE 425 U Bleu PANTONE 653 C Gris PANTONE 425 U ART MODERNE et CONTEMPORAIN Ecole de Paris Tableaux, dessins et sculptures Le Mardi 19 Juin 2012 à 19h. 5, Avenue d’Eylau 75116 Paris Expositions privées: Lundi 18 juin de 10 h. à 18h. Mardi 19 juin de 10h. à 15h. 5, Avenue d’ Eylau 75116 Paris Expert pour les tableaux: Cécile RITZENTHALER Tel: +33 (0) 6 85 07 00 36 [email protected] Assistée d’Alix PIGNON-HERIARD Tel: +33 (0) 1 47 27 76 72 Fax: 33 (0) 1 47 27 70 89 [email protected] EXPERTISES SUR RDV ESTIMATIONS CONDITIONS REPORTS ORDRES D’ACHAt RESERVATION DE PLACES Catalogue en ligne sur notre site www.millon-associes.com בס’’ד MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY FINE ART NEW YORK : Tuesday, June 19, 2012 1 pm TEL AV IV : Tuesday, 19 June 2012 20:00 PARIS : Mardi, 19 Juin 2012 19h AUCTION MATSART USA 444 W. 55th St. New York, NY 10019 PREVIEW IN NEW YORK 444 W. 55th St. New York, NY. 10019 tel. +1-347-705-9820 Thursday June 14 6-8 pm opening reception Friday June 15 11 am – 5 pm Saturday June 16 closed Sunday June 17 11 am – 5 pm Monday June 18 11 am – 5 pm Other times by appointment: 1 347 705 9820 PREVIEW AND SALES ROOM IN TEL AVIV 15 Frishman St., Tel Aviv +972-2-6251049 Thursday June 14 6-10 pm opening reception Friday June 15 11 am – 3 pm Saturday June 16 closed Sunday June 17 11 am – 6 pm Monday June 18 11 am – 6 pm tuesday June 19 (auction day) 11 am – 2 pm Bleu PREVIEW ANDPANTONE 653 C SALES ROOM IN PARIS Gris 5, avenuePANTONE d’Eylau, 425 U 75016 Paris Monday 18 June 10 am – 6 pm tuesday 19 June 10 am – 3 pm live Auction 123 will be held simultaneously bid worldwide and selected items will be exhibited www.artonline.com at each of three locations as noted in the catalog. -

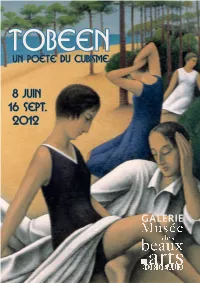

TOBEEN Un Poète Du Cubisme

TOBEEN Un poète du cubisme 8 juin 16 sept. 2012 GALERIE TOBEEN Un poète du cubisme Galerie des Beaux-Arts qui, sous l’impulsion de Picabia, déferle 8 juin – 16 septembre 2012 rue de La Boétie, Metzinger, Juan Gris, Gleizes, Marcel Duchamp, Marcoussis, L’œuvre de Félix-Elie Bonnet dit Tobeen Picabia, Fernand Léger, André Lhote ou (Bordeaux 1880 – Saint-Valery-sur- encore Jacques Villon et Alexandra Exter. Somme, 1938) est celle d’un peintre Son œuvre la plus en vue est Les pétri de régionalisme qui enfourche les Pelotaris, déjà présentée au Salon des préceptes des avant-gardes. Indépendants de 1912 et acquise par le D’origine bordelaise, né en 1880, critique d’art Théodore Duret. Quant au il fait partie du cercle du collectionneur critique du Mercure de France, Gustave et mécène Gabriel Frizeau. Il gardera Kahn, il juge le peintre « compréhensif, des liens d’amitié avec certains de ces robuste, sculptural, dans ses Pelotaris ». intellectuels et artistes entourant l’esthète Autre œuvre remarquable, Le bassin bordelais, comme le critique, tôt disparu, dans le parc de 1913, acquise par Olivier Hourcade et surtout André Lhote Gabriel Frizeau et donnée au musée par avec qui il partage très vite un grand intérêt pour le cubisme. Il s’établit à Paris en 1907 et fréquente les artistes regroupés à Montparnasse, à la Ruche, où il trouve un premier atelier. Cette même année, Picasso devait peindre Les demoiselles d’Avignon et sonner le coup d’envoi du cubisme. Il est aussi un proche du cercle de Puteaux, côtoyant Jacques Villon, Metzinger, Gleizes et prêche, comme eux, pour un art dont le « sujet devenait le métier » (Jacques Villon). -

Impressionist & Modern

Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I 10 October 2019 Lot 8 Lot 2 Lot 26 (detail) Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I Thursday 10 October 2019, 5pm BONHAMS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION IMPORTANT INFORMATION 101 New Bond Street London OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION The United States Government London W1S 1SR India Phillips PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO has banned the import of ivory bonhams.com Global Head of Department REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE into the USA. Lots containing +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF ivory are indicated by the VIEWING [email protected] ANY LOT. INTENDING BIDDERS symbol Ф printed beside the Friday 4 October 10am – 5pm MUST SATISFY THEMSELVES AS lot number in this catalogue. Saturday 5 October 11am - 4pm Hannah Foster TO THE CONDITION OF ANY LOT Sunday 6 October 11am - 4pm Head of Department AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 14 PRESS ENQUIRIES Monday 7 October 10am - 5pm +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 OF THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS [email protected] Tuesday 8 October 10am - 5pm [email protected] CONTAINED AT THE END OF THIS Wednesday 9 October 10am - 5pm CATALOGUE. CUSTOMER SERVICES Thursday 10 October 10am - 3pm Ruth Woodbridge Monday to Friday Specialist As a courtesy to intending bidders, 8.30am to 6pm SALE NUMBER +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 Bonhams will provide a written +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 25445 [email protected] Indication of the physical condition of +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 Fax lots in this sale if a request is received CATALOGUE Julia Ryff up to 24 hours before the auction Please see back of catalogue £22.00 Specialist starts. -

Programmi Svolti

Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca LICEO “P. NERVI – G. FERRARI” P.zza S. Antonio – 23017 Morbegno (So) Indirizzi: Artistico, Linguistico, Scientifico, Scientifico - opz. Scienze applicate, Scienze umane email certificata: [email protected] email Uffici: [email protected] – [email protected] Tel. 0342612541 - 0342610284 / Fax 0342600525 – 0342610284 C.F. 91016180142 https://www.nerviferrari.edu.it ANNO SCOLASTICO 2018/2019 ALLEGATO AL DOCUMENTO DEL CONSIGLIO DI CLASSE V AG LICEO ARTISTICO PROGRAMMI SVOLTI Morbegno, 3 giugno 2019 RELIGIONE ITALIANO INGLESE STORIA FILOSOFIA MATEMATICA FISICA LABORATORIO GRAFICA DISCIPLINE GRAFICHE_LABORATORIO GRAFICA STORIA DELL’ARTE SCIENZE MOTORIE E SPORTIVE ALLEGATO al Documento del Consiglio di classe – V AG Liceo Artistico – a.s. 2018/2019 1 PROGRAMMI SVOLTI LICEO “P. NERVI - G. FERRARI” - Morbegno (SO) MATERIA: RELIGIONE DOCENTE: don DIEGO FOGNINI PROGRAMMA SVOLTO - La responsabilità come impegna di persone autentiche e inserite nella vita quotidiana, non solo scolastica , ma anche sociale - L’etica applicata nelle relazioni, nel proprio lavoro scolastico e non e come deterrente all’illegalità - Fare dell’etica la propria professione - La solidarietà vista come impegno costante in tutte le fragilità sociali che ci circondano - La conoscenza di sé come forza per realizzare progetti di vita [torna all’elenco] ALLEGATO al Documento del Consiglio di classe – V AG Liceo Artistico – a.s. 2018/2019 2 PROGRAMMI SVOLTI LICEO “P. NERVI - G. FERRARI” - Morbegno (SO) MATERIA: ITALIANO DOCENTE: LUIGI NUZZOLI Libri di testo: Roncoroni, Dendi, Il rosso e il blu ed. blu vol. 3, Signorelli Dante, Paradiso, ed. a scelta PROGRAMMA SVOLTO Nota: i titoli delle letture antologiche si riferiscono a quelli del testo in adozione; alcuni testi sono stati forniti in fotocopia 1. -

Coutau-Bégarie & Associés

OLIVIER COUTAU-BÉGARIE ATLANTIQUE - EVENTAILS - MOBILIER & OBJETS D’ART MERCREDI 31 OCTOBRE 2018 - DROUOT - MOBILIER & OBJETS D’ART MERCREDI 31 OCTOBRE - EVENTAILS ATLANTIQUE OLIVIER COUTAU-BÉGARIE COUTAU-BÉGARIE & ASSOCIÉS L ’A TL A NTIQUE LES PEINTRES DU LITTORAL É V ENTA ILS M OBILIER & O BJETS D ’A RT Prochaine Vente Prochaine Vente Mobilier & Objets d’Art L’Atlantique, les peintres du Littoral MERCREDI 31 OCTOBRE 2018 28 novembre 2018 Avril 2019 HOTEL DROUOT - SALLE 6 COUTAU-BÉGARIE & ASSOCIÉS OVV COUTAU-BÉGARIE - AGRÉMENT 2002-113 OLIVIER COUTAU-BÉGARIE, ALEXANDRE DE LA FOREST DIvoNNE, coMMISSAIRES-PRISEURS ASSocIÉS. 60, AVENUE DE LA BOURDONNAIS - 75007 PARIS TEL. : 01 45 56 12 20 - FAX : 01 45 56 14 40 - WWW.coUTAUBEGARIE.coM L ’A TL A NTIQUE LES PEINTRES DU LITTORAL É VENTA ILS M OBILIER & O BJETS D ’A RT MERCREDI 31 OCTOBRE 2018 À 14H00 PARIS - HÔTEL DROUOT - SALLE 6 9, rue Drouot - 75009 Paris Tél. de la salle : +33 (0)1 48 00 20 06 EXPOSITIONS PUBLIQUES Lundi 29 et Mardi 30 octobre 2018 - de 11h00 à 18h00 Mercredi 31 octobre 2018 - de 11h00 à 12h00 VENTE PRÉPARÉE PAR Mathilde Fellmann, Christophe Fumeux (Expert CEDEA) et Pierre Miniussi +33 (0)1 45 56 12 20 EXPERT ÉVENTAILS Georgina Letourmy-Bordier (Expert SFEP) 06 14 67 60 35 - [email protected] RESPONSABLE DE LA VENTE ORDRES D’ACHAT Mathilde Fellmann [email protected] Tél. : +33 (0)1 45 56 12 20 Fax : +33 (0)1 45 56 14 40 24h avant la vente COUTAUBEGARIE.COM Toutes les illustrations de cette vente Suivez la vente en direct sont visibles sur notre site : www.coutaubegarie.com et enchérissez sur : www.drouotlive.com 1 LE P AYS B A SQUE L ’A TL A NTIQUE , DES P EINTRES DU LITTOR A L 3 5 1 1 C. -

Državni Izpit ZAKLJUČNI DOKUMENT RAZREDNEGA SVETA 5

ISTITUTO STATALE DI ISTRUZIONE SUPERIORE CON LINGUA D'INSEGNAMENTO SLOVENA Liceo delle scienze umane e liceo scientifico "S. Gregorčič" Liceo classico „P. Trubar“ DRŽAVNI IZOBRAŽEVALNI ZAVOD S SLOVENSKIM UČNIM JEZIKOM Humanistični in znanstveni licej „S. Gregorčič“ Klasični licej „P. Trubar“ 34170 GORIZIA GORICA via/Ul. Puccini 14 tel. 0481 82123 – Pres./Ravn. 0481 32387 C.F./D.Š. 91021440317 email [email protected] Državni izpit Šolsko leto 2015/16 ZAKLJUČNI DOKUMENT RAZREDNEGA SVETA 5. RAZREDA ZNANSTVENEGA LICEJA OPCIJA UPORABNE ZNANOSTI Z DNE 15. MAJA 2016 odobren na seji razrednega profesorskega zbora dne 13. maja 2016 po 2. odst. 5. čl. OPR št. 323 z dne 23.7.1998 Zaključni dokument razrednega sveta 5. razreda znanstvene smeri (5.čl. pravilnika) 1. Predstavitev razreda a) Sestava razreda a) Razred sestavlja osem dijakov, pet iz Gorice in okoliških vasi, dva dijaka z Laskega in eden iz tržaške pokrajine. Razred je v prvem letniku stel 16 dijakov; 5 jih je zapustilo razred in zamenjalo smer po prvem letniku, ena dijakinja po drugem letniku, druga dijakinja pa se je v tretjem razredu vrnila v Slovenijo; tretja dijakinja je v cetrtem letniku izbrala studij v tujini. Seznam dijakov 1. Daneluzzo Jaroš 2. Furlan Jan 3. Giacomazzi Cecilia 4. Marvin Elena 5. Muller Philip 6. Pahor Katja 7. Papais Franceso 8. Zio Leonardo b) Po prvem letniku, ko je bilo v razredu zaznati kar nekaj tezav s strani vec dijakov, ki jih gre v glavnem pripisati novemu solskemu okolju in bolj zahtevnemu pristopu do solskega dela, je razred zapustilo sest dijakov. V naslednjih letih je v razredu zavladalo pozitivno in konstruktivno vzdušje tako, da je razred postal homogen kolektiv, v katerem je šolsko delo potekalo tekoce in brez vecjih ovir in zastojev. -

Complex Networks Reveal Emergent Interdisciplinary Knowledge in Wikipedia ✉ Gustavo A

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00801-1 OPEN Complex networks reveal emergent interdisciplinary knowledge in Wikipedia ✉ Gustavo A. Schwartz 1,2 In the last 2 decades, a great amount of work has been done on data mining and knowledge discovery using complex networks. These works have provided insightful information about the structure and evolution of scientific activity, as well as important biomedical discoveries. 1234567890():,; However, interdisciplinary knowledge discovery, including disciplines other than science, is more complicated to implement because most of the available knowledge is not indexed. Here, a new method is presented for mining Wikipedia to unveil implicit interdisciplinary knowledge to map and understand how different disciplines (art, science, literature) are related to and interact with each other. Furthermore, the formalism of complex networks allows us to characterise both individual and collective behaviour of the different elements (people, ideas, works) within each discipline and among them. The results obtained agree with well-established interdisciplinary knowledge and show the ability of this method to boost quantitative studies. Note that relevant elements in different disciplines that rarely directly refer to each other may nonetheless have many implicit connections that impart them and their relationship with new meaning. Owing to the large number of available works and to the absence of cross-references among different disciplines, tracking these connections can be challenging. This approach aims to bridge this gap between the large amount of reported knowledge and the limited human capacity to find subtle connections and make sense of them. 1 Centro de Física de Materiales (CSIC-UPV/EHU)—Materials Physics Center (MPC), San Sebastian, Gipuzkoa, Spain. -

Saliency-Based Artistic Abstraction with Deep Learning and Regression Trees

Journal of Imaging Science and Technology R 61(6): 060402-1–060402-9, 2017. c Society for Imaging Science and Technology 2017 Saliency-Based Artistic Abstraction With Deep Learning and Regression Trees Hanieh Shakeri, Michael Nixon, and Steve DiPaola Simon Fraser University, 250—13450 102nd Avenue, Surrey, BC V3T 0A3 E-mail: [email protected] to three or four large masses, and secondly the smaller details Abstract. Abstraction in art often reflects human perception—areas within each mass are painted while keeping the large mass in of an artwork that hold the observer’s gaze longest will generally be 4 more detailed, while peripheral areas are abstracted, just as they mind. are mentally abstracted by humans’ physiological visual process. With the advent of the Artificial Intelligence subfield The authors’ artistic abstraction tool, Salience Stylize, uses Deep of Deep Learning Neural Networks (Deep Learning) and Learning to predict the areas in an image that the observer’s gaze the ability to predict human perception to some extent, this will be drawn to, which informs the system about which areas to keep the most detail in and which to abstract most. The planar process can be automated, modeling the process of abstract abstraction is done by a Random Forest Regressor, splitting the art creation. This article discusses a novel artistic abstraction image into large planes and adding more detailed planes as it tool that uses a Deep Learning visual salience prediction progresses, just as an artist starts with tonally limited masses and system, which is trained on human eye-tracking maps of iterates to add fine details, then completed with our stroke engine. -

Hors-Série Pendant 12 Mois Numéro 1 / Août1 20129

Votre abonnement annuel pour €/mois pendant 12 mois hors-série numéro 1 / août1 20129 - spécial expositions de l’été 2012 - * p.4 paris * p.23 île-de-france * p.26 régions * p.71 étranger www.lequotidiendelart.com 2 euros cliquez et retrouvez le calendrier des expositions du mois édito le quotidien de l’art / hors-série / numéro 1 / a oût 2012 PAGE 02 Expositions : un été radieux ! Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, s’est notamment focalisée sur les artistes s’intéressant à la question de l’histoire. De Gerhard Tout au long de l’année, nos critiques d’art et journalistes Richter au Centre Pompidou à Paris à Jeff Koons à la Fondation parcourent les musées, centres d’art, fondations, en France Beyeler à Bâle, l’art contemporain figure en bonne place dans et à l’étranger, et proposent des comptes rendus, analyses et notre sélection, jusqu’aux plus jeunes artistes, en France ou à critiques des expositions temporaires incontournables. Pour l’étranger, en passant par des rendez-vous comme la triennale ce premier hors-série du Quotidien de l’art, nous vous offrons l’Estuaire qui conduit les visiteurs de Nantes à Saint-Nazaire. une sélection de plus de quatre-vingts expositions à voir durant Cet été, la photographie tient aussi le haut du pavé, des ce mois d’août. Les événements majeurs sont en bonne place, rencontres d’Arles où se distingue la figure de Josef Koudelka comme la Documenta de Cassel, en Allemagne, événement au Guggenheim Museum de New York qui accueille une qui fait un point tous les cinq ans sur les grandes tendances grande rétrospective de la Néerlandaise Rineke Dijkstra. -

Kolokytha, Chara (2016) Formalism and Ideology in 20Th Century Art: Cahiers D’Art, Magazine, Gallery, and Publishing House (1926-1960)

Citation: Kolokytha, Chara (2016) Formalism and Ideology in 20th century Art: Cahiers d’Art, magazine, gallery, and publishing house (1926-1960). Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/32310/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html Formalism and Ideology in 20 th century Art: Cahiers d’Art, magazine, gallery, and publishing house (1926-1960) Chara Kolokytha Ph.D School of Arts and Social Sciences Northumbria University 2016 Declaration I declare that the work contained in this thesis has not been submitted for any other award and that it is all my own work. I also confirm that this work fully acknowledges opinions, ideas and contributions from the work of others. Ethical clearance for the research presented in this thesis is not required. -

I Dream of Painting, and Then I Paint My Dream: Post-Impressionism

ART HISTORY Journey Through a Thousand Years “I Dream of Painting, and Then I Paint My Dream” Week Thirteen: Post-Impressionism Introduction to Neo-Impressionisn – Vincent Van Goh – The Starry Night – A Letter from Vincent to Theo – Paul Gaugin - Gauguin and Laval in Martinique - Paul Cézanne, Turning Road at Montgeroult - Paul Cézanne, The Basket of Apples - Edvard Munch, The Scream – How to Identify Symbolist Art - Arnold Bocklin: Self Portrait With Death - Fernand Khnopff, I Lock my Door Upon Myself Der Blaue Reiter, Artist: Wassily Kandinsky Dr. Charles Cramer and Dr. Kim Grant: "Introduction to Neo-Impressionism” smARThistory (2020) Just a dozen years after the debut of Impressionism, the art critic Félix Fénéon christened Georges Seurat as the leader of a new group of “Neo-Impressionists.” He did not mean to suggest the revival of a defunct style — Impressionism was still going strong in the mid- 1880s — but rather a significant modification of Impressionist techniques that demanded a new label. Fénéon identified greater scientific rigor as the key difference between Neo-Impressionism and its predecessor. Where the Impressionists were “arbitrary” in their techniques, the Neo- Impressionists had developed a “conscious and scientific” method through a careful study of contemporary color theorists such as Michel Chevreul and Ogden Rood. [1] A scientific method Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Bal du Moulin de la Galette, 1876, oil on canvas, 131 x 175 cm (Musée d’Orsay) This greater scientific rigor is immediately visible if we compare Seurat’s Neo- Impressionist Grande Jatte with Renoir’s Impressionist Moulin de la Galette. The subject matter is similar: an outdoor scene of people at leisure, lounging in a park by a river or dancing and drinking on a café terrace.