Groundstone Tool Technology That Relate to the However, Indirect Lines of Evidence That Lie in Manufacture of Nephrite Implements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tula Adze Download

Australian Artefact Fact Sheet Tula adze Tula adzed dish Tula adze slug Tula adze slug Where? Across most of Australia with a focus on Central and Western Australia. The name tula or tuhla comes from the Wangkangurru people of the Simpson Desert. What? The tula adze is a hafted flaked stone tool mostly used for wood working (scraping, adzing and hardwood such as Acacias and Eucalypts. They were also used to butcher animals and to chop plants. When they are used to adze hard wood they blunt quickly and were then resharpened repeatedly by knocking off small flakes along the working edge. In archaeological sites they are usually found as exhausted slugs that have been removed from their hafting, discarded and then replaced. When? Tools such as tulas are rare in archaeological sites and especially places that can be dated. This has meant that there are small numbers that have been securely dated. The oldest dated tula adzes come from rockshelters in the Hamersley Ranges near Newman and Packsaddle dated to between 3,700 and 3,500 years ago. How? Tula adzes are made by flaking a core. They have a wide flat top (platform) that allows easy hafting and they have a curved shaped back (convex). The adzes were usually hafted into the ends of a wooden stick or spear thrower encasing the end of the stick/spear thrower in a resin glue made from spinifex or grevillea resin, kangaroo poo and sand. It took about two tulas to make a boomerang and an undecordated spear thrower would take about eight hours to make with a tula adze. -

The Bow and Arrow in the Book of Mormon

The Bow and Arrow in the Book of Mormon William J. Hamblin The distinctive characteristic of missile weapons used in combat is that a warrior throws or propels them to injure enemies at a distance.1 The great variety of missiles invented during the thousands of years of recorded warfare can be divided into four major technological categories, according to the means of propulsion. The simplest, including javelins and stones, is propelled by unaided human muscles. The second technological category — which uses mechanical devices to multiply, store, and transfer limited human energy, giving missiles greater range and power — includes bows and slings. Beginning in China in the late twelfth century and reaching Western Europe by the fourteenth century, the development of gunpowder as a missile propellant created the third category. In the twentieth century, liquid fuels and engines have led to the development of aircraft and modern ballistic missiles, the fourth category. Before gunpowder weapons, all missiles had fundamental limitations on range and effectiveness due to the lack of energy sources other than human muscles and simple mechanical power. The Book of Mormon mentions only early forms of pregunpowder missile weapons. The major military advantage of missile weapons is that they allow a soldier to injure his enemy from a distance, thereby leaving the soldier relatively safe from counterattacks with melee weapons. But missile weapons also have some signicant disadvantages. First, a missile weapon can be used only once: when a javelin or arrow has been cast, it generally cannot be used again. (Of course, a soldier may carry more than one javelin or arrow.) Second, control over a missile weapon tends to be limited; once a soldier casts a missile, he has no further control over the direction it will take. -

Parsons Site Ground Stone Artifacts

84 _______________________________ ONTARIOARCHAEOLOGY _____________________ No. 65/66, 1998 PARSONS SITE GROUND STONE ARTIFACTS Martin S. Cooper INTRODUCTION Two poll end fragments were recovered, both exhibiting battering at the distal end. One of the poll fragments, which is longitudinally A total of 30 ground stone artifacts was split, is polished on its exterior surface. The recovered, including the bit portions of nine other poll portion is trianguloid in cross section celts, eight additional celt fragments, one and has remnant polishing on all three sur- charmstone or pendant preform, a fragment of faces. The remaining probable celt fragments a stone pipe bowl, one whetstone, a portion of include four pieces that have at least one a large metate, four possible abraders, five polished surface and a spall flake that was hammerstones, and one anvilstone. removed from the bit end of a tool, probably due to impact. DESCRIPTION Charm/Possible Pendant Preform Celts An artifact manufactured from fossiliferous The celt fragments consist of nine bit por- red shale was recovered from a post in the tions (Table 43),'two poll (butt) ends, and five east wall of House 8. This possible charmstone generalized fragments. All of these fragmentary or pendant preform is a flat, ovoid pebble, tools are made from hornblende/chlorite measuring 33 mm in length, 21 mm in width schist. The size of these tools is quite variable and 5 mm in thickness. While the lateral edges ranging from 8 g for the smallest to 351 g for of the pebble have been carefully rounded, the largest. On all nine of the bit portions, and both flat surfaces are highly polished, it is crushing and flaking at the bit end together neither notched nor drilled for suspension. -

Major Work by British Artist William Turnbull Joins the Wadsworth’S Sculptures on Main Street

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Kim Hugo, (860) 838-4082 [email protected] Image files to accompany publicity of this announcement will be available for download at http://press. thewadsworth.org. Email to request login credentials. Major Work by British Artist William Turnbull Joins the Wadsworth’s Sculptures on Main Street Hartford, Conn. (Sept. 19, 2019)— Earlier this week the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art installed Large Horse (1990) one of the largest and most archetypal works by acclaimed twentieth century artist William Turnbull (1922–2012). Also on view is a selection of eight drawings he made between 1950 and 1957. “Art has the power to humanize the urban environment with sculpture having a distinguishing public art role throughout history,” says Thomas J. Loughman, Director and CEO of the Wadsworth. “We are delighted to work with the Turnbull Studio in creating this major addition to the cityscape, particularly as the world is rediscovering Turnbull’s work.” The Wadsworth has been placing sculpture on Main Street for a century beginning with Enoch Woods’ sculpture honoring Nathan Hale which was installed in 1894 and has been on view ever since. Large Horse (1990) by Turnbull joins Tony Smith’s Amaryllis (1965), Conrad Shawcross’ monumental steel Monolith (Optic) (2016), and Woods’ Nathan Hale (1889) on the museum’s front lawn. Turnbull’s casting repertoire began in the early 1950s when his most frequent subjects included bronze masks, heads, and horses. Large Horse (1990) is the product of a late- career return to these three dominant themes. On loan to the Wadsworth from the artist’s estate, the nine-and-a-half-foot bronze is the largest cast metal sculpture Turnbull made. -

Klopsteg, Turkish Archery & the Composite

FfootJiptecc: Sketch of a Turkish archcr at full draw, ready to loose a flight arrow. [Based on a photoK'aph by Dr. Stocklcin published in llalıl I.them “U Palai* Dc Topkapou (Vicux Scrail)”. Mitnm. <k U Ltbratic Kanaat 1931 page 17. Information supplied by Society of Archcr-Antiquaries member Jamcr. H. Wiggins. | TURKISH ARCHERY AND THE COMPOSITE BOW by Paul E. Klopsteg F ormer D irector of R esearch N orthwestern T echnological I nstitute A Review of an old Chapter in the Chronicles of Archery and a Modern Interpretation Enlarged Third Edition Simon Archery Foundation The Manchester Museum, The University Manchester M139PL, Kngland Also published by the Simon Archcry Foundation: A Bibliography of Arthtry by Fred Lake and HaJ W right 1974 ISBN 0 9503199 0 2 Brazilian India» Arcbeiy bv E. G. Heath and Vilma Chiara 1977 ISBN 0 9503199 1 0 Toxopbilns by Roger Ascham 1985 ISBN 0 9503199 0 9 @ Paul E. Klopsteg, 1934, 1947 and 1987 First published by rhe author in the U.S.A. in 1934 Second edition, Revised published by the author in the U.S.A. in 1947 This enlarged edition published in 1987 JSBN 0 9503199 3 7 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Butler & Tanner Ltd, Frome and London c^ pur TABLE 0F CONTENTS Pa& In troduction ....................... ............................... ................................. Y|J Dr. Paul E. Klopsteg. Excerpts about him from articles written by him ...................................... ; .............................................................. IX Preface to the Second E d itio a ............................................................... xiii Preface to the First E dition........................................................ I The Background of Turkish Archery..................................... 1 II The Distance Records of the Turkish Bow......................... -

Marquesan Adzes in Hawai'i: Collections, Provenance

University of Hawai‘i at Hilo HOHONU 2015 Vol. 13 outside the Marquesas have never been found in the Marquesan Adzes in Hawai‘i: island group (Allen 2014:11), but this groundbreaking Collections, Provenance, and discovery was spoiled by the revelation that a yachtsman who had visited both places had donated the artifacts, Sourcing and apparently mixed them up before doing so (202). Hattie Le‘a Wheeler Gerrish Researchers with access to other sources of information Anthropology 484 can avoid possible pitfalls. Garanger (1967) laments, Fall 2014 “What amount of dispersed artifacts were illegally exported by the numerous voyagers drawn by the Abstract mirage of the “South Seas” and now irrevocably lost to In 1953, Jack and Leah Wheeler returned to science?” (390). It is my intent to honor the wishes of Hawai'i with 13 adze heads and one stone pounder my maternal grandparents, Jack and Leah Wheeler, that they had obtained during their travels in the Marquesas, the artifacts they (legally) brought home to Hawai'i from Tuamotus, and Society Islands. The rather general the East Pacific not be “irrevocably lost to science.” I provenance of these artifacts presents a challenge will attempt to source their stone artifacts, and discover that illustrates the benefits of combining XRF with what geochemistry can tell us of these tools of uncertain other sources of information, and the limits of current provenance. My experience strengthens my belief that knowledge of Pacific geochemistry. EDXRF reveals that combining non-destructive EDXRF with other sources five of the artifacts are likely made of stone from the of information such as oral history, written accounts, Eiao quarry, and the rest may represent five additional and morphological comparison, enhances the value of sources. -

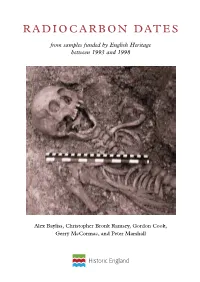

Radiocarbon Dates 1993-1998

RADIOCARBONDATES RADIOCARBONDATES RADIOCARBON DATES This volume holds a datelist of 1063 radiocarbon determinations carried out between 1993 and 1998 on behalf of the Ancient Monuments Laboratory of English Heritage. It contains supporting information about the samples and the sites producing them, a comprehensive bibliography, and two indexes for reference from samples funded by English Heritage and analysis. An introduction provides discussion of the character and taphonomy between 1993 and 1998 of the dated samples and information about the methods used for the analyses reported and their calibration. The datelist has been collated from information provided by the submitters of the samples and the dating laboratories. Many of the sites and projects from which dates have been obtained are now published, although developments in statistical methodologies for the interpretation of radiocarbon dates since these measurements were made may allow revised chronological models to be constructed on the basis of these dates. The purpose of this volume is to provide easy access to the raw scientific and contextual data which may be used in further research. Alex Bayliss, Christopher Bronk Ramsey, Gordon Cook, Gerry McCormac, and Peter Marshall Front cover:Wharram Percy cemetery excavations. (©Wharram Research Project) Back cover:The Scientific Dating Research Team visiting Stonehenge as part of Science, Engineering, and Technology Week,March 1996. Left to right: Stephen Hoper (The Queen’s University, Belfast), Christopher Bronk Ramsey (Oxford -

Chapter 8: Fire Fighter Tools and Equipment 27

Chapter 8: Fire Fighter Tools and Equipment 27 Chapter 8: Fire Fighter Tools and Equipment Matching 1. E (page 273) 3. I (page 281) 5. C (page 284) 7. D (page 276) 9. F (page 276) 2. A (page 273) 4. B (page 284) 6. G (page 269) 8. H (page 274) 10. J (page 284) Multiple Choice 1. C (page 272) 6. B (page 274) 11. D (page 272) 16. C (page 275) 2. D (page 280) 7. A (page 272) 12. C (page287) 17. D (page 284) 3. D (page 268) 8. A (page 277) 13. A (page 284) 18. B (page 281) 4. B (page 284) 9. B (page 286) 14. A (page 277) 19. D (page 284) 5. C (page 268) 10. D (page 277) 15. D (page 277) 20. D (page 286) Vocabulary 1. Claw bar: A tool with a pointed claw-hook on one end and a forked- or f lat-chisel pry on the other end that can be used for forcible entry. (page 274) 2. Reciprocating saw: A saw powered by either an electric motor or a battery motor that rapidly pulls the saw blade back and forth. (page 278) 3. Overhaul: The phase in which you examine the fire scene carefully and ensure that all hidden fires are extinguished. (page 285) 4. Gripping pliers: A hand tool with a pincer-like working end that can also be used to bend wire or hold smaller objects. (page 269) 5. Crowbar: A straight bar made of steel or iron with a forked-like chisel on the working end. -

Provenance Studies of Polynesian Basalt Adze Material: a Review and Suggestions for Improving Regional Data Bases

Provenance Studies of Polynesian Basalt Adze Material: A Review and Suggestions for Improving Regional Data Bases MARSHALL 1. WEISLER PACIFIC ARCHAEOLOGISTS have long been interested in the settlement of Polyne sia, the origin of colonizing groups at distant archipelagoes, and subsequent social interaction between island societies (see, for example, Howard 1967; Irwin 1990; Kirch and Green 1987). Early material studies in Polynesia inferred migration routes and social interaction from the distribution of similar architecture, especially marae (Emory 1943; also R. Green 1970), adzes (Emory 1961), and fishhooks (Sinoto 1967). The identification of exotic raw materials and finished artifacts throughout Polynesia eliminates the ambiguity often presented by linking stylistic similarities across space and through time. In relation to the long history of identifying exotic lithic materials from archaeological sites (see, for example, Grimes 1979), the compositional analysis of oceanic obsidians was begun quite recently (Key 1968). The efficacy of chemical characterization of artifacts and quarry material in New Zealand provided the in centive to apply similar techniques to obsidian of the southwest Pacific, where several large sources were known and where the archaeological distribution of this material was tl)ought to be widespread (Ambrose 1976). Although it has been possible to define the spread and interaction of human groups in the southwest Pacific by determining the spatial and temporal distribution of obsidian and pot tery, these materials are restricted to a few areas in Polynesia. Consequently, the effort to document prehistoric interaction throughout Polynesia must proceed without using obsidian or pottery. This leaves only basalt (debitage, formed arti facts, and oven stones), pearlshell, and volcanic glass as material for distributional studies (Best et al. -

The Necklace As a Divine Symbol and As a Sign of Dignity in the Old Norse Conception

MARIANNE GÖRMAN The Necklace as a Divine Symbol and as a Sign of Dignity in the Old Norse Conception Introduction In the last century a wooden sculpture, 42 cm tall, was found in a small peat-bog at Rude-Eskildstrup in the parish of Munke Bjergby near Soro in Denmark. (Picture 1) The figure was found standing right up in the peat with its head ca. 30 cm below the surface. The sculpture represents a sit- ting man, dressed in a long garment with two crossed bands on its front. His forehead is low, his eyes are tight, his nose is large, and he wears a moustache and a pointed chin-beard. Part of his right arm is missing, while his left arm is undamaged. On his knee he holds an object resembling a bag. Around his neck he wears a robust trisected necklace.1 At the bottom the sculpture is finished with a peg, which indicates that it was once at- tached to a base, which is now missing (Mackeprang 1935: 248-249). It is regarded as an offering and is usually interpreted as depicting a Nordic god or perhaps a priest (Holmqvist 1980: 99-100; Ström 1967: 65). The wooden sculpture from Rude-Eskildstrup is unique of its kind. But his characteristic trisected necklace is of the same type as three famous golden collars from Västergötland and Öland. The sculpture as well as the golden necklaces belong to the Migration Period, ca. 400-550 A.D. From this period of our prehistory we have the most frequent finds of gold, and very many of the finds from this period are neck-ornaments. -

Locating an Antiquarian Initiative in a Late 19Th Century Colonial

th Basak, B. 2020. Locating an Antiquarian Initiative in a Late 19 Century Colonial Bofulletin the History of Archaeology Landscape: Rivett-Carnac and the Cultural Imagining of the Indian Sub-Continent. Bulletin of the History of Archaeology, 30(1): 1, pp. 1–9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/bha-610 RESEARCH PAPER: ASIA/PACIFIC Locating an Antiquarian Initiative in a Late 19th Century Colonial Landscape: Rivett-Carnac and the Cultural Imagining of the Indian Sub-Continent Bishnupriya Basak In this paper I seek to understand antiquarian practices in a colonial context in the Indian sub-continent with reference to J.H. Rivett-Carnac who was a member of the Bengal Civil Service. Covering varied subjects like ‘ancient cup marks on rocks,’ spindle whorls, votive seals or a solitary Buddha figure, Rivett- Carnac’s writings reflect an imagining of a native landscape with wide-ranging connections in myths, symbolisms and material cultures which cross-cut geographical borders. I show how an epistemology of comparative archaeology was formed through the ways in which he compared evidence recorded from different parts of India to those documented in Great Britain and northern Europe. This was held together by ideas of tribal/racial migrations. I am arguing that a distinctive form of antiquarianism was unfolding in an ambiguous, interstitial space which deconstructs any neat binaries between the colonizer and the colonized. Recent researches have argued for many antiquarianisms which this paper upholds. With his obsession of cup marks Rivett-Carnac built a new set of interconnections in late 19th century Britain where the Antiquity of man was the pivot around which debates and theories circulated. -

Estimating the Scale of Stone Axe Production: a Case Study from Onega Lake, Russian Karelia Alexey Tarasov 1 and Sergey Stafeev 2

Estimating the scale of stone axe production: A case study from Onega Lake, Russian Karelia Alexey Tarasov 1 and Sergey Stafeev 2 1. Institute of Linguistics, Literature and History, Pushkinskaya st.11, 185910 Petrozavodsk, Russia, Email: [email protected] 2. Institute of Applied Mathematical Research, Pushkinskaya st.11, 185910 Petrozavodsk, Russia, Email: [email protected] Abstract: The industry of metatuff axes and adzes on the western coast of Onega Lake (Eneolithic period, ca. 3500 – 1500 cal. BC) allows assuming some sort of craft specialization. Excavations of a workshop site Fofanovo XIII, conducted in 2010-2011, provided an extremely large assemblage of artefacts (over 350000 finds from just 30 m2, mostly production debitage). An attempt to estimate the output of production within the excavated area is based on experimental data from a series of replication experiments. Mass-analysis with the aid of image recognition software was used to obtain raw data from flakes from excavations and experiments. Statistical evaluation assures that the experimental results can be used as a basement for calculations. According to the proposed estimation, some 500 – 1000 tools could have been produced here, and this can be qualified as an evidence of “mass-production”. Keywords: Lithic technology; Neolithic; Eneolithic; Karelia; Fennoscandia; stone axe; adze; gouge; craft specialization; mass-analysis; image recognition 1. Introduction 1.1 Chopping tools of the Russian Karelian type; Cultural context and chronological framework This article is devoted to quite a small and narrow question, which belongs to a much wider set of problems associated with an industry of wood-chopping tools of the so-called Russian Karelian (Eastern Karelian) type from the territory of the present-day Republic of Karelia of the Russian Federation.