Galileo's Compass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

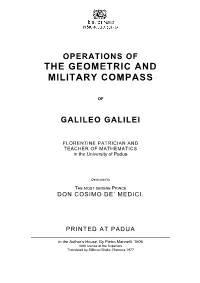

Operations of the Geometric and Military Compass

OPERATIONS OF THE GEOMETRIC AND MILITARY COMPASS OF GALILEO GALILEI FLORENTINE PATRICIAN AND TEACHER OF MATHEMATICS in the University of Padua Dedicated to THE MOST SERENE PRINCE DON COSIMO DE’ MEDICI. PRINTED AT PADUA in the Author’s House, By Pietro Marinelli. 1606 With license of the Superiors Translated by Stillman Drake, Florence 1977 CONTENTS Dedication............................................................................................................................ 5 Prologue .............................................................................................................................. 6 Operation I Division of a line .................................................................................................................. 7 Operation II How in any given line we can take as many parts as may be required .............................. 8 Operation III How these same lines give us two, and even infinitely many, scales for altering one map into another larger or smaller ............................................................................... 8 Operation IV The rule-of-three solved by means of a compass and these same Arithmetic Lines .................................................................................................................................... 9 Operation V The inverse rule-of-three resolved by means of the same lines ......................................... 10 Operation VI Rule for monetary exchange .............................................................................................. -

Sources: Galileo's Correspondence

Sources: Galileo’s Correspondence Notes on the Translations The following collection of letters is the result of a selection made by the author from the correspondence of Galileo published by Antonio Favaro in his Le opere di Galileo Galilei,theEdizione Nazionale (EN), the second edition of which was published in 1968. These letters have been selected for their relevance to the inves- tigation of Galileo’s practical activities.1 The information they contain, moreover, often refers to subjects that are completely absent in Galileo’s publications. All of the letters selected are quoted in the work. The passages of the letters, which are quoted in the work, are set in italics here. Given the particular relevance of these letters, they have been translated into English for the first time by the author. This will provide the international reader with the opportunity to achieve a deeper comprehension of the work on the basis of the sources. The translation in itself, however, does not aim to produce a text that is easily read by a modern reader. The aim is to present an understandable English text that remains as close as possible to the original. The hope is that the evident disadvantage of having, for example, long and involute sentences using obsolete words is compensated by the fact that this sort of translation reduces to a minimum the integration of the interpretation of the translator into the English text. 1Another series of letters selected from Galileo’s correspondence and relevant to Galileo’s practical activities and, in particular, as a bell caster is published appended to Valleriani (2008). -

Here from the Main Rings to Enceladus M.K

Block Schedule Wednesday 7/27 Thursday 7/28 Friday 7/29 8:30 Introduction 8:40 Ring Objects 9:00 Dense Ring Ring 9:20 Structure Composition 9:40 10:00 10:20 10:40 Dense Ring Ring F ring 11:00 Structure Particle 11:20 (continued) Properties 11:40 12:00 12:20 12:40 Lunch Lunch 13:00 Lunch 13:20 13:40 14:00 Ring Particle Ring Origins 14:20 Sizes 14:40 Dusty Rings 15:00 OPUS 15:20 15:40 Intro to Posters Ring 16:00 Dusty Rings Evolution 16:20 and 16:40 Ring Environments Poster 17:00 Session 17:20 Discussion Discussion 17:40 18:00 18:30 19:00 Dinner on Campus BBQ at Treman Park Open 19:30 2 Wedsneday Morning, July 27 8:30-8:40 Welcome, Introduction 8:40-9:00 Revisiting the Self-Gravity Wakes Granola Bar Model: More Data, More Parameters J. E. Colwell, R. G. Jerousek, J. H. Cooney 9:00-9:20 Self-Gravity Wakes and the Viscosity of Dense Planetary Rings G. R. Stewart 9:20-9:40 B Ring Gray Ghosts in Cassini UVIS Occultations M. Sremˇcevi´c L.W. Esposito, J.E. Colwell, N. Albers 9:40-10:00 Simulating the B ring M. Lewis 10:00-10:20 Break 10:20-10:40 Noncircular Features in Saturn's Rings: I. The Cassini Division R. G. French, P. D. Nicholson, J. Colwell, E. A. Marouf, N. J. Rappaport, M. Hedman, K. Lonergan, C. McGhee-French, and T. Sepersky 10:40-11:00 Noncircular Features in Saturn's Rings: II. -

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE Body temperature measurement from the 17th century to the present days Original Body temperature measurement from the 17th century to the present days / Angelini, Emma; Grassini, Sabrina; Parvis, Marco; Parvis, Luca; Gori, Andrea. - ELETTRONICO. - (2020), pp. 1-6. ((Intervento presentato al convegno 15th IEEE International Symposium on Medical Measurements and Applications - MeMeA2020 tenutosi a Bari, Italy nel 1-3 June 2020 [10.1109/MeMeA49120.2020.9137339]. Availability: This version is available at: 11583/2841349 since: 2020-08-25T14:41:07Z Publisher: IEEE Published DOI:10.1109/MeMeA49120.2020.9137339 Terms of use: openAccess This article is made available under terms and conditions as specified in the corresponding bibliographic description in the repository Publisher copyright IEEE postprint/Author's Accepted Manuscript ©2020 IEEE. Personal use of this material is permitted. Permission from IEEE must be obtained for all other uses, in any current or future media, including reprinting/republishing this material for advertising or promotional purposes, creating new collecting works, for resale or lists, or reuse of any copyrighted component of this work in other works. (Article begins on next page) 07 October 2021 Body temperature measurement from the 17th century to the present days Emma Angelini Sabrina Grassini Department of Applied Science and Technology Department of Applied Science and Technology Politecnico di Torino Politecnico di Torino Torino, Italy Torino, Italy [email protected] -

Bibliography Explains Galileo’S Scientific Contributions II, Grand Duke of Tuscany

Ga li l eo’s Battle for the He aven s AIRING OCTOBER 29, 2002 Galileo White, Michael. Galilei,Galileo. Galileo Galilei:Inventor, Astronomer, Starry Messenger and Rebel. In 1609, Galileo became the first Books Woodbridge, CT: Blackbirch Press, 1999. astronomer to systematically observe Brighton, Catherine. Covers the life and accomplishments of the heavens with a telescope.The Galileo’s Treasure Box. Galileo, including an examination of the following year he published a book of New York: Walker and Company, 2001. conflict between the scientists of the time his findings, which included drawings and the Catholic Church. ya of the Moon’s Introduces the reader to Galileo through phases and the the eyes of his daughter Virginia as she discovery of examines the tools in his study. c ya Videos four moons Drake,Stillman. Galileo’s Battle for the Heavens. orbiting Jupiter. Galileo: AVery Short Introduction. WGBH Boston Video, 2002. a New York : Oxf o r d Univer s i t y Pres s , 20 0 1 . Examines Galileo’s astronomical discov- Presents a short introduction to Galileo’s eries, shares correspondence with his life and achievements focusing on his daughter, and chronicles his clash with conflicts with theologians but supporting the Catholic Church. ya a the hypothesis that he was an advocate for the Catholic Church. ya a Galileo:On the Shoulders of Giants. Steeplechase Entertainment, 1999. Fisher,Leonardo. Introduces children to Galileo’s discover- Galileo. ies, his conflict with the Catholic Church, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992. and his mentorship of Cosimo de Medici Bibliography Explains Galileo’s scientific contributions II, Grand Duke of Tuscany. -

The Legend of Galileo, Icon of Modernity

Carrol, William E. The legend of Galileo, icon of modernity Sapientia Vol. LXIV, Fasc. 224, 2008 Este documento está disponible en la Biblioteca Digital de la Universidad Católica Argentina, repositorio institucional desarrollado por la Biblioteca Central “San Benito Abad”. Su objetivo es difundir y preservar la producción intelectual de la institución. La Biblioteca posee la autorización del autor para su divulgación en línea. Cómo citar el documento: Carrol, William E. “The legend of Galileo, icon of modernity”[en línea]. Sapientia. 64.224 (2008). Disponible en: http://bibliotecadigital.uca.edu.ar/repositorio/revistas/legend-of-galileo-icon-modernity.pdf [Fecha de consulta:..........] (Se recomienda indicar fecha de consulta al final de la cita. Ej: [Fecha de consulta: 19 de agosto de 2010]). WILLIAM E. CARROL University of Oxford The Legend of Galileo, Icon of Modernity Writing in Le Monde in February 2007, Serge Galam, a physicist of CNRS (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique) and member of the Center for Research in Applied Epistemology of the École Polytechnique, discussed scientific arguments concerning the role of human beings in global warming. In what is all too frequent in contemporary analyses of science, ethics, and public policy, Galam invoked the image of Galileo and his opponents in the seventeenth century. He noted that, when Galileo concluded that “the Earth was round, the unanimous consensus against him was that the Earth was flat,” and this despite the fact that Galileo “had demonstrated his conclusion.” Galam then brought his point closer to our own day: “in a similar way,” the Nazis rejected the theory of relativity because it was put forth by Einstein and was, accordingly, a Jewish and, hence, “degenerate theory.” It is quite some- thing to think that it is was the sphericity of the Earth which Galileo was defending. -

Moonstruck: How Realistic Is the Moon Depicted in Classic Science Fiction Films?

MOONSTRUCK: HOW REALISTIC IS THE MOON DEPICTED IN CLASSIC SCIENCE FICTION FILMS? DONA A. JALUFKA and CHRISTIAN KOEBERL Institute of Geochemistry, University of Vienna. Althanstrasse 14, A-1090 Vienna, Austria (E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]) Abstract. Classical science fiction films have been depicting space voyages, aliens, trips to the moon, the sun, Mars, and other planets, known and unknown. While it is difficult to critique the depiction of fantastic places, or planets about which little was known at the time, the situation is different for the moon, about which a lot of facts were known from astronomical observations even at the turn of the century. Here we discuss the grade of realism with which the lunar surface has been depicted in a number of movies, beginning with George Méliès’ 1902 classic Le Voyage dans la lune and ending, just before the first manned landing on the moon, with Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Many of the movies present thoughtful details regarding the actual space travel (rockets), but none of the movies discussed here is entirely realistic in its portrayal of the lunar surface. The blunders range from obvious mistakes, such as the presence of a breathable atmosphere, or spiders and other lunar creatures, to the persistent vertical exaggeration of the height and roughness of lunar mountains. This is surprising, as the lunar topography was already well understood even early in the 20th century. 1. Introduction Since the early days of silent movies, the moon has often figured prominently in films, but mainly as a backdrop for a variety of more or (most often) less well thought-out plots. -

The Behavior of Spokes in Saturn's B Ring

The Behavior of Spokes in Saturn’s B Ring C.J. Mitchella,∗, C.C. Porcoa, H.L. Donesb, J.N. Spitalec aCassini Imaging Central Laboratory for Operations, 4750 Walnut Street Suite 205, Boulder, CO 80301, USA bSouthwest Research Institute, 1050 Walnut Street, Boulder, CO 80302, USA cPlanetary Science Institute, 1700 E. Ft. Lowell, Suite 106, Tucson, AZ 85719, USA Abstract We present the first results from Cassini ISS observations aimed at determin- ing both the short-term and long-term behavior of the spokes in Saturn’s B ring. We have observed multiple spokes which appear between images where there was not a spoke before. The radial termini of these new spokes expand radially at ∼ 0.5 km/s in both the inward and outward directions and both towards and away from corotation. Defining a spoke’s activity as the area-integrated op- tical depth over the region of the ring it covers, we find that the majority of spokes which are found in multiple images are either increasing or decreasing in activity. In addition, in analyzing the shapes and motions of spokes, we find the azimuthal profiles to be well-fitted by Gaussians for the majority of spokes. We have found that several of the imaged spokes were undergoing an “active” phase during which the spoke’s optical depth increases and the spoke grows both azimuthally and radially. We interpret these motions to be either due to the Lorentz force acting on dust grains charged by a very high temperature plasma or the group velocity of an advancing spoke-forming front. -

The British War Film, 1939-1980: Culture, History, and Genre

The British War Film, 1939-1980: Culture, History, and Genre by Kevin M. Flanagan B.A., College of William and Mary, 2006 M.A., North Carolina State University, 2009 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2015 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Kevin M. Flanagan It was defended on April 15, 2015 and approved by Colin MacCabe, Distinguished Professor, Department of English Adam Lowenstein, Associate Professor, Department of English David Pettersen, Assistant Professor, Department of French and Italian Dissertation Advisor: Lucy Fischer, Distinguished Professor, Department of English ii Copyright © by Kevin M. Flanagan 2015 iii THE BRITISH WAR FILM, 1939-1980: CULTURE, HISTORY, AND GENRE Kevin M. Flanagan, Ph.D. University of Pittsburgh, 2015 This dissertation argues that discussions of war representation that privilege the nationalistic, heroic, and redemptively sacrificial strand of storytelling that dominate popular memory in Britain ignore a whole counter-history of movies that view war as an occasion to critique through devices like humor, irony, and existential alienation. Instead of selling audiences on what Graham Dawson has called “the pleasure culture of war” (a nationally self-serving mode of talking about and profiting from war memory), many texts about war are motivated by other intellectual and ideological factors. Each chapter includes historical context and periodizing arguments about different moments in British cultural history, explores genre trends, and ends with a comparative analysis of representative examples. -

Educational Learning Theories: 2Nd Edition Molly Zhou Dalton State College, [email protected]

GALILEO, University System of Georgia GALILEO Open Learning Materials Education Open Textbooks Education Spring 2015 Educational Learning Theories: 2nd Edition Molly Zhou Dalton State College, [email protected] David Brown Dalton State College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/education-textbooks Part of the Educational Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Zhou, Molly and Brown, David, "Educational Learning Theories: 2nd Edition" (2015). Education Open Textbooks. 1. https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/education-textbooks/1 This Open Textbook is brought to you for free and open access by the Education at GALILEO Open Learning Materials. It has been accepted for inclusion in Education Open Textbooks by an authorized administrator of GALILEO Open Learning Materials. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Educational Learning Theories Molly Y. Zhou David Brown 2 Educational Learning Theories edited by Molly Y. Zhou Dalton State College David Brown Dalton State College December, 2017 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC-SA). Cite the book: Zhou, M., & Brown, D. (Eds.). (2017). Educational learning theories. Retrieved from [link] 3 Permission to Use Acknowledgements Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for Permission to Use by Creative Commons licenses or authors or proper copy right holders: Chapter 1 Behaviorism New World Encyclopedia. (2016, May 26). Behaviorism. Retrieved from http://web.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Behaviorism Standridge, M. (2002). Behaviorism. In M. Orey (Ed.), Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology. Retrieve from http://epltt.coe.uga.edu/index.php?title=Behaviorism Chapter 2 Stages of Cognitive Development Wood, K. -

Early Telescopes and Ancient Scientific Instruments in the Paintings of Jan Brueghel the Elder

Early Telescopes and Ancient Scientific Instruments in the Paintings of Jan Brueghel the Elder Pierluigi Selvelli and Paolo Molaro INAF, Osservatorio Astronomico di Trieste, Italy Abstract: Ancient instruments of high interest for research on the origin and diffusion of early scientific devices in the late XVI – early XVII centuries are reproduced in three paintings by Jan Brueghel the Elder. We investigated the nature and the origin of these instruments, in particular the spyglass depicted in a painting dated 1609-1612 that represents the most ancient reproduction of an early spyglass, and the two sophisticated spyglasses with draw tubes that are reproduced in two paintings, dated 1617-1618. We suggest that these two instruments may represent early examples of keplerian telescopes. Concerning the other scientific instruments, namely an astrolabe, an armillary sphere, a nocturnal, a proportional compass, surveying instruments, a Mordente's compass, a theodolite, etc., we point out that most of them may be associated with Michiel Coignet, cosmographer and instrument maker at the Court of the Archduke Albert VII of Hapsburg in Brussels. Published in ASTRONOMY AND ITS INSTRUMENTS BEFORE AND AFTER GALILEO, Edited by Luisa Pigatto and Valeria Zanini 2009, p193-208 1. The Historical and Cultural Context The reign of the Archdukes Albert VII of Hapsburg-Austria and Isabella Clara Eugenia of Hapsburg-Spain, (1596-1625), certainly represented a key period of the history of the Low Countries. The Archdukes ruled the (catholic) South, while the (calvinist) North Provinces were governed by the regents, the Princes Maurice and Henry of Nassau-Orange, who represented the wealthy merchant class. -

Discovery of Oxygen Kα X-Ray Emission from the Rings of Saturn

Discovery of Oxygen K X-ray Emission from the Rings of Saturn Anil Bhardwaj1,*, Ronald F. Elsner1, J. Hunter Waite, Jr.2, G. Randall Gladstone3, Thomas E. Cravens4, and Peter G. Ford5 1 NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, NSSTC/XD12, 320 Sparkman Drive, Huntsville, AL 35805, USA; [email protected], [email protected] 2 Department of Atmospheric, Oceanic and Space Sciences, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA; [email protected] 3 Southwest Research Institute, San Antonio, P.O. Drawer 28510, TX 78228, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS 66045, USA; [email protected] 5 Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, 70 Vassar Street, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA; [email protected] * on leave from: Space Physics Laboratory, Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre, Trivandrum 695022, India; [email protected] Running header: X-ray emission from Saturn’s rings Astrophysical Journal Letters In press, May 2005 Page 1 of 14 Abstract Using the Advanced CCD Imaging Spectrometer (ACIS), the Chandra X-ray Observatory (CXO) observed the Saturnian system for one rotation of the planet (~37 ks) on 20 January, 2004, and again on 26–27 January, 2004. In this letter we report the detection of X-ray emission from the rings of Saturn. The X-ray spectrum from the rings is dominated by emission in a narrow (~130 eV wide) energy band centered on the atomic oxygen K fluorescence line at 0.53 keV. The X-ray power emitted from the rings in the 0.49–0.62 keV band is 84 MW, which is about one-third of that emitted from Saturn disk in the photon energy range 0.24–2.0 keV.