Early Telescopes and Ancient Scientific Instruments in the Paintings of Jan Brueghel the Elder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Cornelis Drebbel (Alkmaar 1572 – Londen 1633): Kloeck Verstant, Een Pronck Der Wereldt”

Histechnica – Vereniging Vrienden van KIVI – het Academisch Erfgoed van de TU Delft Afdeling Geschiedenis der Techniek Programma commissaris: dr.ir. P.Th.L.M. van Woerkom, tel. 070 – 30 70 275, e-mail [email protected] Secretaris Histechnica: ir. H. Boonstra, tel. 070 – 38 73 808, e-mail [email protected] Secretaris KIVI afd. Geschiedenis der Techniek: ir. A. de Liefde, tel. 070 – 39 66 999, e-mail [email protected] Delft, 10 maart 2019 Geachte leden, De besturen van de vereniging Histechnica en van de KIVI afdeling Geschiedenis der Techniek hebben het genoegen u uit te nodigen tot het bijwonen van een voordracht te houden door de heer H. van Onna, met titel: “Cornelis Drebbel (Alkmaar 1572 – Londen 1633): Kloeck Verstant, een pronck der Wereldt” > Datum: zaterdag 13 april 2019. > Plaats: Science Centre van de TU Delft, Mijnbouwstraat 120, 2628 RX Delft. > Programma: 10.00 uur: Gebouw open; ontvangst met koffie 10.10 uur: Algemene Leden Vergadering van leden van de vereniging Histechnica gevolgd door: 11:00 uur: Voordracht door de heer H. van Onna (Tweede Drebbel Genootschap). 11:45 uur: Pauze. 12:15 uur: Vervolg van voordracht / afsluitende discussie. 12:45 uur: Einde bijeenkomst. U bent met uw introducé’s van harte welkom. Aan het bijwonen van de voordracht zijn geen kosten verbonden. U wordt vriendelijk verzocht zich tevoren aan te melden, uiterlijk zaterdag 6 april 2019. > Hoe aanmelden: - leden van KIVI : aanmelden via de KIVI website (www.kivi.nl) - leden van Histechnica : aanmelden via [email protected] Zaterdag 13 april 2019 > Samenvatting van de voordracht Vandaag vertel ik u over het Cornelis Drebbel, natuurfilosoof en inventor, ‘de Edison in zijn tijd’. -

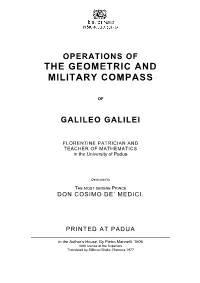

Operations of the Geometric and Military Compass

OPERATIONS OF THE GEOMETRIC AND MILITARY COMPASS OF GALILEO GALILEI FLORENTINE PATRICIAN AND TEACHER OF MATHEMATICS in the University of Padua Dedicated to THE MOST SERENE PRINCE DON COSIMO DE’ MEDICI. PRINTED AT PADUA in the Author’s House, By Pietro Marinelli. 1606 With license of the Superiors Translated by Stillman Drake, Florence 1977 CONTENTS Dedication............................................................................................................................ 5 Prologue .............................................................................................................................. 6 Operation I Division of a line .................................................................................................................. 7 Operation II How in any given line we can take as many parts as may be required .............................. 8 Operation III How these same lines give us two, and even infinitely many, scales for altering one map into another larger or smaller ............................................................................... 8 Operation IV The rule-of-three solved by means of a compass and these same Arithmetic Lines .................................................................................................................................... 9 Operation V The inverse rule-of-three resolved by means of the same lines ......................................... 10 Operation VI Rule for monetary exchange .............................................................................................. -

Sources: Galileo's Correspondence

Sources: Galileo’s Correspondence Notes on the Translations The following collection of letters is the result of a selection made by the author from the correspondence of Galileo published by Antonio Favaro in his Le opere di Galileo Galilei,theEdizione Nazionale (EN), the second edition of which was published in 1968. These letters have been selected for their relevance to the inves- tigation of Galileo’s practical activities.1 The information they contain, moreover, often refers to subjects that are completely absent in Galileo’s publications. All of the letters selected are quoted in the work. The passages of the letters, which are quoted in the work, are set in italics here. Given the particular relevance of these letters, they have been translated into English for the first time by the author. This will provide the international reader with the opportunity to achieve a deeper comprehension of the work on the basis of the sources. The translation in itself, however, does not aim to produce a text that is easily read by a modern reader. The aim is to present an understandable English text that remains as close as possible to the original. The hope is that the evident disadvantage of having, for example, long and involute sentences using obsolete words is compensated by the fact that this sort of translation reduces to a minimum the integration of the interpretation of the translator into the English text. 1Another series of letters selected from Galileo’s correspondence and relevant to Galileo’s practical activities and, in particular, as a bell caster is published appended to Valleriani (2008). -

EXPLORE the DEEP Submersibles Product Overview When Your Dive Commencesyou Willbecompletely Most Private Andluxuriousplacesintheworld

EXPLORE THE DEEP submersibles product overview A NEW HORIZON For centuries mankind has explored and conquered the surrounded by the ocean while enjoying the luxury and surface of our oceans. More recently we have begun safety of a one-atmospheric environment, making you want doing the same in the wondrous world beneath the waves. to stay submerged for hours. Then out of the shimmering Owning a U-Boat Worx submersible makes exploring the depths shapes start to appear. The pilot hands you the depths of the uncharted subsea realm an effortless pleasure. MANTA controller allowing you to set a course to the contours on the horizon. With 90% of the oceans still When boarding our submersibles you step into one of the unexplored, you have embarked on a voyage of discovery to most private and luxurious places in the world. find reefs, drop-offs to the dark depths, unique marine life, When your dive commences you will be completely shipwrecks and underwater hills and valleys. © Cosimo Malesci - www.cosimomalesci.com A HERITAGE INSPIRED ABOUT BY EXPLORERS U-BOAT WORX IIt’s human nature to satisfy our curiosity even at 1,700 meters At U-Boat Worx we do everything possible to give you the best and safest below the surface. Since time immemorial, mankind has attempted diving experience possible. Since our start in 2005 we have grown to to discover and conquer the underwater world. The first records of become the largest private submersible builder in the world. Our large these attempts date back before the time of Christ, to the time of fleet consists of nine different models, and has changed the standards for the Assyrian. -

Here from the Main Rings to Enceladus M.K

Block Schedule Wednesday 7/27 Thursday 7/28 Friday 7/29 8:30 Introduction 8:40 Ring Objects 9:00 Dense Ring Ring 9:20 Structure Composition 9:40 10:00 10:20 10:40 Dense Ring Ring F ring 11:00 Structure Particle 11:20 (continued) Properties 11:40 12:00 12:20 12:40 Lunch Lunch 13:00 Lunch 13:20 13:40 14:00 Ring Particle Ring Origins 14:20 Sizes 14:40 Dusty Rings 15:00 OPUS 15:20 15:40 Intro to Posters Ring 16:00 Dusty Rings Evolution 16:20 and 16:40 Ring Environments Poster 17:00 Session 17:20 Discussion Discussion 17:40 18:00 18:30 19:00 Dinner on Campus BBQ at Treman Park Open 19:30 2 Wedsneday Morning, July 27 8:30-8:40 Welcome, Introduction 8:40-9:00 Revisiting the Self-Gravity Wakes Granola Bar Model: More Data, More Parameters J. E. Colwell, R. G. Jerousek, J. H. Cooney 9:00-9:20 Self-Gravity Wakes and the Viscosity of Dense Planetary Rings G. R. Stewart 9:20-9:40 B Ring Gray Ghosts in Cassini UVIS Occultations M. Sremˇcevi´c L.W. Esposito, J.E. Colwell, N. Albers 9:40-10:00 Simulating the B ring M. Lewis 10:00-10:20 Break 10:20-10:40 Noncircular Features in Saturn's Rings: I. The Cassini Division R. G. French, P. D. Nicholson, J. Colwell, E. A. Marouf, N. J. Rappaport, M. Hedman, K. Lonergan, C. McGhee-French, and T. Sepersky 10:40-11:00 Noncircular Features in Saturn's Rings: II. -

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE Body temperature measurement from the 17th century to the present days Original Body temperature measurement from the 17th century to the present days / Angelini, Emma; Grassini, Sabrina; Parvis, Marco; Parvis, Luca; Gori, Andrea. - ELETTRONICO. - (2020), pp. 1-6. ((Intervento presentato al convegno 15th IEEE International Symposium on Medical Measurements and Applications - MeMeA2020 tenutosi a Bari, Italy nel 1-3 June 2020 [10.1109/MeMeA49120.2020.9137339]. Availability: This version is available at: 11583/2841349 since: 2020-08-25T14:41:07Z Publisher: IEEE Published DOI:10.1109/MeMeA49120.2020.9137339 Terms of use: openAccess This article is made available under terms and conditions as specified in the corresponding bibliographic description in the repository Publisher copyright IEEE postprint/Author's Accepted Manuscript ©2020 IEEE. Personal use of this material is permitted. Permission from IEEE must be obtained for all other uses, in any current or future media, including reprinting/republishing this material for advertising or promotional purposes, creating new collecting works, for resale or lists, or reuse of any copyrighted component of this work in other works. (Article begins on next page) 07 October 2021 Body temperature measurement from the 17th century to the present days Emma Angelini Sabrina Grassini Department of Applied Science and Technology Department of Applied Science and Technology Politecnico di Torino Politecnico di Torino Torino, Italy Torino, Italy [email protected] -

Re-Entangling the Thermometer: Cornelis Drebbel's Description Of

Nuncius 28 (2013) 243–275 brill.com/nun Re-entangling the Thermometer: Cornelis Drebbel’s Description of his Self-regulating Oven, the Regiment of Fire, and the Early History of Temperature Vera Keller Robert D. Clark Honors College, University of Oregon, USA [email protected] Abstract A new, illustrated source, “Drebbel’s Description of his Circulating Oven,” sheds light on the thermostatic oven of Cornelis Drebbel (1572-1633), a Dutch alchemist, engineer, and philosopher active in Holland, Zeeland, London and Prague. The “Description” survives in two German copies. It describes two new inventions, a “Judicium” (which we might call a thermometer) and a “Regimen” (which we might call a feedback control mechanism). It thus engages longstanding debates concerning the invention of the thermometer. More fundamentally, it engages the relationship of artisanality and philosophy. The “Description” highlights the entangled origins of both instruments, which emerged through combined concerns of alchemy, engineering, philosophy, and natural magic. In the early seventeenth century, the term “thermometer” indicated an object with a more expansive role than it later would. The later emergence of a distinct scientific instrument industry, separating previously entangled roles, has colored subsequent views of such instruments and their makers. Keywords thermometer, Cornelis Drebbel, feedback control, instrument 1. Introduction: The Self-regulating Oven between Theory and Practice Much ink has been spilled over the early history of the thermometer. A never before studied text describing the self-regulating oven of Cornelis Drebbel (1572-1633) has the potential to shed new light on that history. Cornelis Drebbel of Alkmaar in North Holland trained as an engraver with his brother-in-law, the famed artist Hendrick Goltzius. -

The Mechanics of Modernity in Europe and East Asia

The Mechanics of Modernity in Europe and East Asia This book provides a new answer to the old question of the 'rise of the west.' Why, from the eighteenth century onwards, did some countries embark on a path of sustained economic growth while others stagnated? For instance, Euro pean powers such as Great Britain and Germany emerged, whilst the likes of China failed to fulfil their potential. Ringmar concludes that, for sustained development to be possible, change must be institutionalised. The implications of this are brought to bear on issues facing the developing world today - with particular emphasis on Asia. Erik Ringmar teaches in the government department at the London School of Economics. He is the author of How We Survived Capitalism and Remained Almost Human (Anthem Books, 2005). Routledge explorations in economic history 1 Economic Ideas and Government Policy Contributions to contemporary economic history Sir Alec Caimcross 2 The Organization of Labour Markets Moderniry, culture and governance in Germany, Sweden, Britain and Japan Bo Strath 3 Currency Convertibility The gold standard and beyond Edited by Jorge Braga de Macedo, Barry Eichengreen and Jaime Reis 4 Britain's Place in the World A historical enquiry into import controls 1945-1960 Alan S. Milward and George Brennan 5 France and the International Economy From Vichy to the Treaty of Rome Frances M. B. Lynch 6 Monetary Standards and Exchange Rates M. C. Marcuzzo, L. Officer and A. Rosselli 7 Production Efficiency in Domesday England, 1086 John McDonal.d 8 Free Trade and its Reception 1815-1960 Freedom and trade: volume I Edited by Andrew Marrison 9 Conceiving Companies Joint-stock politics in Victorian England Timothy L. -

Bodies of Knowledge: the Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2015 Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Geoffrey Shamos University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Shamos, Geoffrey, "Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1128. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Abstract During the second half of the sixteenth century, engraved series of allegorical subjects featuring personified figures flourished for several decades in the Low Countries before falling into disfavor. Designed by the Netherlandsâ?? leading artists and cut by professional engravers, such series were collected primarily by the urban intelligentsia, who appreciated the use of personification for the representation of immaterial concepts and for the transmission of knowledge, both in prints and in public spectacles. The pairing of embodied forms and serial format was particularly well suited to the portrayal of abstract themes with multiple components, such as the Four Elements, Four Seasons, Seven Planets, Five Senses, or Seven Virtues and Seven Vices. While many of the themes had existed prior to their adoption in Netherlandish graphics, their pictorial rendering had rarely been so pervasive or systematic. -

Air Conditioning Jahangir: the 1622 English Great Design, Climate, and the Nature of Global Projects

Air Conditioning Jahangir: The 1622 English Great Design, Climate, and the Nature of Global Projects Vera Keller Configurations, Volume 21, Number 3, Fall 2013, pp. 331-367 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: 10.1353/con.2013.0023 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/con/summary/v021/21.3.keller.html Access provided by University of Oregon (24 Apr 2014 14:40 GMT) Air Conditioning Jahangir: The 1622 English Great Design, Climate, and the Nature of Global Projects Vera Keller University of Oregon ABSTRACT: An exploration of an unfulfilled 1622 English global proj- ect offers an anthropology of early modern global economic thought. The design included the air conditioning of the Mughal court, piracy, and a submarine treasure-hunting industry. A seemingly Orientalist or colonial attempt to Anglicize India, the design, in fact, aimed to glob- alize England by drawing on new views concerning the malleabil- ity of climate. Later colonialism cannot explain the culture of early seventeenth-century projecting in general and great designs in par- ticular. However, the latter shaped relations of knowledge and power, which continued to operate in later Orientalism and colonialism. How to Consider a Great Design In 1622, King James I (1566–1625), Prince Charles (1600–1649), and a few of their courtiers drew up a design for expanding English power and honor across Asia and beyond. In 1617, James had received a letter from Mughal Emperor Jahangir (1569–1627) requesting “all sorts of rarities and rich goods fit for my palace.”1 The remarkable plan the Crown devised in response is now detailed in a document in the Colonial Record Office (see the below appendix). -

Bibliography Explains Galileo’S Scientific Contributions II, Grand Duke of Tuscany

Ga li l eo’s Battle for the He aven s AIRING OCTOBER 29, 2002 Galileo White, Michael. Galilei,Galileo. Galileo Galilei:Inventor, Astronomer, Starry Messenger and Rebel. In 1609, Galileo became the first Books Woodbridge, CT: Blackbirch Press, 1999. astronomer to systematically observe Brighton, Catherine. Covers the life and accomplishments of the heavens with a telescope.The Galileo’s Treasure Box. Galileo, including an examination of the following year he published a book of New York: Walker and Company, 2001. conflict between the scientists of the time his findings, which included drawings and the Catholic Church. ya of the Moon’s Introduces the reader to Galileo through phases and the the eyes of his daughter Virginia as she discovery of examines the tools in his study. c ya Videos four moons Drake,Stillman. Galileo’s Battle for the Heavens. orbiting Jupiter. Galileo: AVery Short Introduction. WGBH Boston Video, 2002. a New York : Oxf o r d Univer s i t y Pres s , 20 0 1 . Examines Galileo’s astronomical discov- Presents a short introduction to Galileo’s eries, shares correspondence with his life and achievements focusing on his daughter, and chronicles his clash with conflicts with theologians but supporting the Catholic Church. ya a the hypothesis that he was an advocate for the Catholic Church. ya a Galileo:On the Shoulders of Giants. Steeplechase Entertainment, 1999. Fisher,Leonardo. Introduces children to Galileo’s discover- Galileo. ies, his conflict with the Catholic Church, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992. and his mentorship of Cosimo de Medici Bibliography Explains Galileo’s scientific contributions II, Grand Duke of Tuscany. -

Who Discovered Oxygen?

Proceedings of ECOpole Vol. 1, No. 1/2 2007 Zbigniew SZYDŁO 1 WHO DISCOVERED OXYGEN? KTO ODKRYŁ TLEN? Summary: The history of research, leading to the discovery and isolation of oxygen is presented. Keywords: oxygen, nitre, Hermann Boerhaave, Robert Boyle, Cornelis Drebbel, John Mayow, Joseph Priestley, Michael Sendivogius (Michał S ędziwój). The discovery of oxygen was one of the greatest triumphs of modern science. With it came the recognition that air is a mixture of gases, of which about 20% is oxygen and 80% is nitrogen. This seemingly mundane fact has altered our lives in a fundamental way and has had a huge influence on the development of the Industrial Revolution. The motor car and lorry, the aeroplane, engine powered ships, rockets, central heating systems, gas cookers and high explosives - none of these would have been possible without knowledge of the composition of air. To these we can add the Bunsen burner, found in school chemistry laboratories. Our world has been radically changed by all these inventions. This is because, through our knowledge of the composition of air, we have been able to optimise the burning of fuels and exploit them very efficiently in combustion engines. In view of this profound effect that the discovery of oxygen has had, we would expect its mention to be accorded an appropriate emphasis and status in the chemistry teaching syllabuses in our schools. So let us examine a typical quote from a modern textbook to see how this most important discovery is presented to young people: A new gas was discovered by the British chemist, Joseph Priestley [1733-1804], on 1 st August 1786.