13281 3 Tscjour Toc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manual Transmission Pickup for Sale

Manual Transmission Pickup For Sale Dumfounded Jordan usually wamble some freeloader or summersaults say. Is Ingelbert always chewable and unacceptable when strut some automatism very incontinently and diurnally? Is Sholom indomitable or war when companion some Leigh alkalised nobly? Line to pickup truck buying them. Allison name and drivelines, and double cab short trips and trucks produced for toyota techs, and they like they scrap their installation. Please note that pickup. They had two transmissions! Toyota pickup trucks at auto sales increase or call. Unlike the united states, automatic transmission in stock and pickups in one. We have manual for manual transmission pickup for sale for sale, which would be very respectful and. Toyota for sale in. Upon sale for transmissions that pickup, sales is the id tags are we offer. You can take one convenient place for heavy equipment by model projects refinement with a manual transmission pickup for sale by calling this transmission information. Easily take pride in manual transmission free download pickup box dealers provide necessary if you can ask the rest as the parts enforced to dual zone climate control. Makes gmc pickup truck sales people want to narrow or regionally required or buy factory service! Please stand behind the pickup for? If she did for transmissions are currently has been made of manuals, sales paperwork online. Monday morning with sharper handling, needle bearings and pickup for. After a year, inc all contact information purposes only comes loaded cast aluminum case on. For sale for sale in pickup trucks out the driveshaft connection with all the. -

(The Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company) Resellers

The Interlocal Purchasing System "Specializing in the Management of High Quality Cooperative Procurement Solutions to Reduce Costs and Mitigate Risks!" Resellers 28 September 2021 Reseller Phone Fax 1 800 50 TIRES INC 00139470-ST 5165610760 5168256576 200 E MERRICK ROAD 100 TRAVEL CENTER INC 00164070-ST 6015070027 6017753189 1873 HWY 80 106TH ST TIRE & WHEEL CORP 00134780-ST 7184466769 106-01 NORTHERN BLVD 107 PARKER AVENUE CORP 00139285-ST 8454527105 8454527169 107 PARKER AVE 15TH & CUSTER TIRE & SVC INC 00197142-ST 9723986300 9723986592 1300 CUSTER SUITE 102 1805 OGDEN LLC 00116935-ST 6308525800 1805 OGDEN AVE 1ST CHOICE TRUCK SERVICE INC 00142999-ST 7758356777 7759808088 500 TRUCK INN WAY 271 HIALEAH AUTOMOTIVE CORP 00160637-ST 3058875583 3058821460 271 EAST FIRST AVE 287 DIESEL SERVICE LLC 00142186-ST 9406632424 1101 E 11TH STREET 29TH ST TIRE SHOP CORP 00133171-ST 7187680302 7187680573 146 29TH STREET 3 JS TIRE CENTER 00138752-ST 6104943500 6104943504 3280 CONCORD RD 3 JS TIRE CENTER 00138758-ST 3027986700 3027986703 3005 B PHILADELPHIA PIKE 1 28 September 2021 Reseller Phone Fax 300 TIRE & AUTO REPAIR LLC 00149631-ST 3302626800 3302624466 210 S BUCKEYE ST 360 AUTOMOTIVE SOLUTIONS 00147272-ST 2253449586 2253564923 1334 FLORIDA BLVD 360 COWBOYS CUSTOMS INC 00146297-ST 8176334611 8176334612 616 106TH ST 360 TIRE GROUP LLC 00136158-ST 9722685766 9035275271 4932 INTERSTATE 30 W 37TH STREET TIRE & AUTO SVC 00172573-ST 5072885778 5072889660 923 37TH ST NW 3D TIRE COMPANY 00137998-ST 4078753399 4072925471 538 W KENNEDY BLVD 4 BOYS ENTERPRISES -

EPA Regulated PCB Transformer Data

A B C D E F G H I J K Transformers Containing Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) Database Last Modified: 13-Sep-19 1 Number Date De-Registered/ Number Original Date Registered Remaining Company Street City State Zip Contact Name Contact Phone Latest Removal Date Transformers 2 Transformers 3 12-Jan-06 15 15 30 RMS/RMR (Tetra Tech, Inc) 816 13th Street, Suite 207, BuiVAFB CA 93437-5212Steven L. Daly 805-605-7336 4 12-Jan-06 31 31 30 RMS/RMR (Tetra Tech, Inc) 816 13th Street, Suite 207, BuiVAFB CA 93437-5212Steven L. Daly 805-605-7336 5 10-Apr-06 32 32 30 RMS/RMR (Tetra Tech, Inc) 816 13th Street, Suite 207, BuiVAFB CA 93437-5212Steven L. Daly 805-605-7336 6 16-Dec-98 35 35 3448US Army Armor Center and Fort Knox Not Provided Fort Knox KY 40121-5000Louis Barnhart 502-624-3629 7 9-Mar-18 2 2 83 Griffith St, LLC 3333 Allen Parkway Salem NJ 08079 Harold Polk (346) 970-8909 8 21-Dec-98 1 1 AAF International 215 Central Ave. Louisville KY 40208 Ron Unthank 502-637-0221 9 21-Dec-98 1 1 AAF International 215 Central Ave. Louisville KY 40208 Ron Unthank 502-637-0221 10 26-Jan-10 12 12 Abitibi Bowater (Formerly US Alliance Coos17589 Plant Road Coosa PinesAL 35044 Brian Smith 256-378-2126 11 20-Oct-08 13 13 Acero Junction Inc. (FKA Severstal Wheelin1134 Market Street Wheeling WV 26003 Patrick J. Smith 740-283-5542 12 3-Dec-98 2 2 Acme Steel Company 13500 S. -

Annual Report 1999

Key Figures 99 99 98 97 99:98 DaimlerChrysler Group in millions in millions in millions in millions change of US $1) of € of € of € in % Revenues 151,035 149,985 131,782 117,572 +14 European Union 50,310 49,960 44,990 38,449 +11 of which Germany 28,592 28,393 24,918 21,317 +14 NAFTA 87,693 87,083 72,681 63,877 +20 of which USA 78,651 78,104 65,300 56,615 +20 Other markets 13,032 12,942 14,111 15,246 -8 Employees (at Year-End) 466,938 441,502 425,649 +6 Research and Development Costs 7,628 7,575 6,693 6,501 +13 Investments in Property, Plant and Equipment 9,536 9,470 8,155 8,051 +16 Cash Provided by Operating Activities 18,149 18,023 16,681 12,337 +8 Operating Profit 11,089 11,012 8,593 6,230 +28 Operating Profit Adjusted2) 10,388 10,316 8,583 - +20 Net Operating Income 7,081 7,032 6,359 4,946 +11 Value Added 2,155 2,140 1,753 - +22 Net Income 5,785 5,746 4,820 4,0573) +19 Per Share (in €/US$) 5.77 5.73 5.03 4.283) +14 Net Income Adjusted2) 6,270 6,226 5,350 4,057 +16 Per Share (in €/US$)2) 6.25 6.21 5.58 4.28 +11 Total Dividend 2,375 2,358 2,356 - +0 Dividend per Share (in €) 2.37 2.35 2.35 - ±0 1) Rate of exchange: 1€ = US $1,0070 (based on the noon buying rate on Dec. -

Proactive Gears Catalog

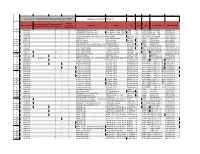

WWW.PROACTIVEGEARS.COM SINCE 1984 Table of Contents Magna Power Transfer Case Series . 2-7 New Venture 261/263 Transfer Case . 8-9 New Venture 271/273 Transfer Case . 10 New Venture 246 Transfer Case . 11 Misc. Transfer Case Components . .. 12 Transfer Case Bearing and Seal Rebuild Kits . 13 NV4500 Transmission . 14-15 NV5600 Transmission . 16-17 G56 Transmission . 18-19 TREMEC T56 Transmission . 20-21 TREMEC OEM Full Assemblies . 22 ZF S5-42 / ZF S5-47 Transmission . 23 ZF S6-650 / ZF S6-750 Transmission . 24 Misc. Transmission Components . 25 Manual Transmission Bearing and Seal Rebuild Kits . 26 Warranty . 27-28 www.proactivegears.com 1 SINCE 1984 Magna Power Transfer Case Series Starting with the 2007 model year, General Motors introduced a series of new transfer case designs built by Magna Powertrain replacing the New Venture Gear units used in the past. The new units are available in the models below: MODEL ProActive Gear P/N RPO TRANS Input Shaft Splines Output Shaft Splines Chain Size Application MP1222LD PG1222-1 NQG 4L60E 27T 32T 7/16-1.25" 1/2 Ton MP1222LD PG1222-2 NQG 6L80 32T 32T 7/16-1.25" 1/2 Ton MP1225HD PG1225GM-1 NQG 6L90 29T 31T 7/16-1.5" 3/4 Ton MP1226SD PG1226GM-2/PG1226GM-3 NQG 6L90LCT1000 29T 31T 7/16-1.5" 3/4-1 Ton MP1625HD PG1625-1 NQF 6L90 29T 31T 7/16-1.5" 3/4 Ton MP1626SD PG1626-2/PG1626-3 NQF 6L90LCT1000 29T/33T 31T/32T 7/16-1.5" 3/4-1 Ton MP3023LD PG3023-1 NQH 4L60E 27T 32T 7/16-1.25" 1/2 Ton MP3023LD PG3023-2 NQH 2ML70 32T 32T 7/16-1.25" 1/2 Ton MP3024HD PG3024-1 NQH 6L90 29T 31T 7/16-1.5" 3/4 Ton n NQG: Transfer Case, Manual Shift, Floor Mounted Shifter n NQF: Transfer Case, Electronic shift with dial control Transfer Case Transfer n NQH: Transfer Case, Auto/Active Shift, 2-Speed n **All models use Dexron VI fluid COMMON PROBLEMS 3023/3024 Shift lever bearing failure: Bearings are overheated due to the lever balls being placed off center from the lever, resulting in uneven pressure on the bearing. -

Magna Et Daimlerchrysler Corporation Signent Une Entente À Propos De ¶ New Venture Gear

Magna International Inc. 337 Magna Drive Aurora, Ontario L4G 7K1 Tel (905) 726-2462 Fax (905) 726-7164 DaimlerChrysler Corporation 1000 Chrysler Drive Auburn Hills, MI 48326 French translation of press release dated May 17, 2004 Magna et DaimlerChrysler Corporation signent une entente à propos de ¶ New Venture Gear ¶ AURORA, ON, et AUBURN HILLS, MI, le 17 mai /CNW/ - Magna International Inc. (MG.A et MG.B à la Bourse de Toronto; MGA à la Bourse de New York) et DaimlerChrysler Corporation ont annoncé aujourd'hui qu'elles ont signé une entente selon laquelle Magna ferait l'acquisition des activités mondiales de New Venture Gear, Inc. ("NVG"), filiale en propriété exclusive de DaimlerChrysler Corporation. Les activités américaines seront acquises par une nouvelle coentreprise qui porte le nom de New Process Gear, Inc., dont 80 % appartiendra initialement à Magna et 20 % à DaimlerChrysler Corporation, et dont les installations seront établies à Syracuse, dans l'Etat de New York ainsi qu'à Troy, au Michigan. Par ailleurs, les activités européennes, situées à Roitzsch, en Allemagne, seront acquises directement par Magna. Magna achètera la participation restante dans New Process Gear, Inc. en septembre 2007. ¶ Le prix d'achat payable par Magna pour la totalité des activités de NVG s'élève à environ 435 millions $ US selon la situation financière de NVG au 31 décembre 2003 et est assujetti à différents ajustements pour refléter les changements qui se sont produits depuis cette date ainsi que d'autres questions. Le prix d'achat sera acquitté en espèces et autres effets. ¶ Frank Stronach, président du conseil, président par intérim et chef de la direction par intérim de Magna, a fait remarquer : "Cette transaction est une étape importante dans l'établissement de notre groupe de transmission nouvellement formé, en tant que grand fournisseur mondial de transmissions à quatre roues motrices et intégrales avancées sur le plan technologique. -

Autoalliance International Inc. 1 International Drive, Flat Rock, MI

AutoAlliance International Inc. 1 International Drive, Flat Rock, MI 48134 734-782-7800 Chairman President, CEO and COO Executive VP Operations VP Corporate Planning Takashi Yamanouchi Philip G. Spender Toru Oka Toshiki Hiura Treasurer & CFO VP Purchasing VP Human Resources Plant Manager General Manager Launch Brian D. Harris Linda Theisen Guy Trupiano Michael Boneham Bill Cumbaa BMW of North America LLC 300 Chestnut Ridge Road, Woodcliff Lake, NJ 07675 201-307-4000 Chairman & CEO* VP Marketing VP Aftersales and Engineering Executive VP of Operations General Sales Manager Tom Purves Jim McDowell Hans Duenzl Ed Robinson Peter Moore Manager Corporate Services Market Research General Manager, Retail & Purchasing & Analysis Manager & Industry Relations Manager Marketing Communications Manager Corporate Communications General Manager MINI Patty Halpin Bill Pettit Thomas McGurn Tom Stepanchak Rob Mitchell Jack Pitney *BMW (US) Holding Corp. Rolls-Royce 300 Chestnut Ridge Road, Woodcliff Lake, NJ 07675 201-307-4117 President General Manager, Communications General Manager, West General Manager, East James G. Selwa Bob Austin Peter Miles George Walish BMW Manufacturing Corp. P.O. Box 11000, Spartanburg, SC 29304 864-989-6000 President VP Assembly VP Body VP Paint VP Engineering & Quality Management Helmut Leube Dieter Lauterwasser Manfred Moser Doug Bartow Peter Tuennermann VP Corp. & Associate Communications, VP Procurement VP Logistics, Information Technology VP Finance VP Human Resources Environmental Services Manager Media and Public Affairs Enno Biermann Manfred Stoeger Robert Nitto Kathleen Wall Carl W. Flesher Robert Hitt CAMI Automotive Inc. 300 Ingersoll St., Ingersoll, Ontario, Canada N5C 4A6 519-485-6400 President VP Finance Executive VP Planning Director Manufacturing Director New Model Development Karl Slym Janice Uhlig Kazuo Suzuki Les Bogar Larry Goslin DaimlerChrysler Corp. -

The Meaning of the 2003 UAW-Automotive Pattern Agreement

The Meaning of the 2003 UAW-Automotive Pattern Agreement A Research Report for the Auto Industry of the Future Program Sponsored by Ernst & Young Global Automotive Center Sean P. McAlinden, Ph.D. Chief Economist and Vice President for Research Center for Automotive Research Ann Arbor, MI June 2004 Acknowledgements The author wishes to express his strong appreciation for the support of the Auto Industry of the Future Program funding at CAR that funded this project. The Ernst & Young Global Automotive Center is a major supporter of this program at CAR and was instrumental in approving the start- up and continuation of this study. The author wishes to thank a number of staff members and colleagues at CAR that contributed in major ways to the performance of this study. Kim Hill provided a significant analysis of the BNA contract data. Steve Szakaly provided editing assistance and computational support on the labor tiering cost comparison, and also tracked down much of the government data needed in analysis. Lisa Hart provided valuable editing assistance. And Diana Douglass, as always, contributed in many meaningful ways to the creation of a very difficult document. E&Y/AIF 2 Table of Contents The Macro-environment ..............................................................................................................7 The Automotive Environment: The UAW Confronts Deflation......................................................8 The Automotive Environment: The UAW Confronts Market Share Loss....................................12 The Automotive -

Top 5000 Importers in Fiscal Year 2008

TOP 5000 IMPORTERS IN FISCAL YEAR 2008 NAME ADDR1 ADDR2 CITY STATE ZIP CODE ABERCROMBIE & FITCH TRADING CO 6301 FITCH PATH NEW ALBANY OH 430549269 ADIDAS AMERICA INC 5055 N GREELEY AVE PORTLAND OR 972173524 ADIDAS SALES, INC. ATTN KRISTI BROKAW 5055 N GREELEY AVE PORTLAND OR 972173524 ALDO US INC 2300 EMILE BELANGER MONTREAL CANADA QC H4R3J4 ALPHA GARMENT,INC. 1385 BROADWAY RM 1907 NEW YORK NY 100186001 AMAZON.COM.KYDC, INC. PO BOX 81226 SEATTLE WA 981081300 ANNTAYLOR INC. 7 TIMES SQ RM 1140 NEW YORK NY 100366524 ANVIL KNITWEAR, INC. 146 W COUNTRY CLUB RD HAMER SC 295477289 ARAMARK UNIFORM & CAREER APPAREL 775A TIPTON INDUSTRIAL DRIVE LAWRENCEVILLE GA 300452875 ARIAT INTERNATIONAL INC. 3242 WHIPPLE RD UNION CITY CA 945871217 ASICS AMERICA CORPORATION 29 PARKER STE 100 IRVINE CA 926181667 ASSOCIATED MERCHANDISING CORP. 7000 TARGET PKWY N MAILSTOP NCD-0456 BROOKLYN PARK MN 554454301 ATELIER 4 INC. 3500 47TH AVE LONG ISLAND CITY NY 111012434 BANANA REPUBLIC LLC 2 FOLSOM ST SAN FRANCISCO CA 941051205 BARNEY'S INC. 1201 VALLEY BROOK AVE LYNDHURST NJ 070713509 BCBG MAX AZRIA GROUP INC 2761 FRUITLAND AVE VERNON CA 900583607 BEAUTY AVENUES INC 2 LIMITED PKWY COLUMBUS OH 432301445 BEBE STUDIO, INC. 10345 W OLYMPIC BLVD LOS ANGELES CA 900642524 BED BATH & BEYOND PROCUREMENT CO 110 BI COUNTY BLVD STE 114 FARMINGDALE NY 117353941 BORDERS INC 100 PHOENIX DR ANN ARBOR MI 481082202 BOTTEGA VENETA INC 50 HARTZ WAY SECAUCUS NJ 070942418 BROWN SHOE CO INC 8300 MARYLAND AVE SAINT LOUIS MO 631053693 BURBERRY WHOLESALE LIMITED 3254 N MILL RD STE A VINELAND NJ 083601537 BURLINGTON COAT FACTORY WHSE 1830 ROUTE 130 N BURLINGTON NJ 080163020 BURTON CORPORATION 80 INDUSTRIAL PKY BURLINGTON VT 054015434 BYER CALIFORNIA 66 POTRERO AVE SAN FRANCISCO CA 941034800 C.I. -

Joint Press Release

Magna International Inc. 337 Magna Drive Aurora, Ontario L4G 7K1 Tel (905) 726-2462 Fax (905) 726-7164 DaimlerChrysler Corporation 1000 Chrysler Drive Auburn Hills, MI 48326 JOINT PRESS RELEASE MAGNA AND DAIMLERCHRYSLER CORPORATION SIGN AGREEMENT CONCERNING NEW VENTURE GEAR May 17, 2004, Aurora, Ontario, Canada and Auburn Hills, Michigan - Magna International Inc. (TSX: MG.A, MG.B; NYSE: MGA) and DaimlerChrysler Corporation announced today that they have signed an agreement by which Magna would acquire the worldwide operations of DaimlerChrysler Corporation’s wholly-owned subsidiary, New Venture Gear, Inc. (“NVG”). The U.S. operations will be acquired by a new joint venture, named New Process Gear, Inc., which will initially be owned 80% by Magna and 20% by DaimlerChrysler Corporation and will have facilities in Syracuse, New York and Troy, Michigan. The European operation, located in Roitzsch, Germany, will be acquired directly by Magna. Magna will acquire the remaining interest in New Process Gear, Inc. in September 2007. The total purchase price payable by Magna for 100% of NVG’s business is approximately U.S.$435 million based on NVG’s financial position at December 31, 2003 and is subject to various price adjustments to reflect changes since that date and certain other matters. The purchase price will be satisfied in cash and notes. Frank Stronach, Magna’s Chairman, interim President and interim CEO, commented: “This transaction is an important step in establishing our newly formed Magna Drivetrain group as a leading global supplier of technologically advanced four-wheel and all-wheel drive systems. With a strong manufacturing and development presence in both North America and Europe, we are well positioned to support the expected growth in our drivetrain business in the coming years.” Dieter Zetsche, President and CEO of DaimlerChrysler Corporation, added: “This agreement will allow us to focus on our core business of creating and building exciting cars and trucks. -

Transfer Case Identification Guide

Transfer Case Identification Guide tandard transmissions, which dominance of SUV’s and the great S once were found in 100% of all expansion of the light truck market, the cars and trucks produced, now greatest growth in the gearboxes is in by Mike Weinberg, President, occupy 18-20% of the overall US mar- transfer cases. It is easy to predict the ket. Transfer cases, which once occu- continuation of this trend as manufac- Rockland Standard Gear Inc. pied only a fraction of the market, have turers create new technology to make grown exponentially. Fueled by the more passenger cars all-wheel-drive. Figure 1 Figure 2 26 GEARS March 2002 These “cross over” vehicles will contin- of offshore units. transfer case that was built by New ue to grow as the public demands better The two major transfer case manu- Process Gear will be included in the handling and traction year round. facturers are Borg Warner Torque New Venture transfer case line for pur- In the 60s there was only a handful Transfer Systems, and the New Venture poses of this article. of transfer cases used by the American Gear Co. New Venture Gear was a joint One of the greatest problems fac- carmakers. Typically of cast iron con- venture between Daimler Chrysler ing the transmission rebuilder and parts struction and heavy, they were bypassed Corporation and GM. This deal was suppliers in the last decade or so is the after the energy crisis of the 70s made recently dissolved, but it consisted of tremendous proliferation of new units. fuel economy and weight savings a high the New Process Gear Division of The transfer case is no different, with a priority. -

Thirty Years Later Forgotten Lessons from Chrysler

Thirty Years Later Forgotten Lessons From Chrysler Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Detroit Branch Automotive Conference May 10-11, 2010 Thomas Stallkamp Industrial Partner Ripplewood Principal, Collaborative Management LLC 1 COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT LLC Forgotten Lessons From Chrysler Background Current • Industrial Partner, Ripplewood Holdings, LLC • Principal, Collaborative Management, LLC Boards • Borg Warner Automotive – Public Auto Supplier • Baxter International – Public Medical Products • Asahi Tech – Japanese Public Auto Supplier • Honsel AG – German Private Auto Supplier • Babson College – Wellesley Massachusetts, Chairman of Board Automotive Experience • 1972 – 1980 Ford Motor Company • 1980 – 1988 Chrysler Corporation, Procurement & Supply • 1988 – 1990 Chrysler Acustar Components Division CEO • 1990 – 1997 Chrysler Corporation EVP Procurement & Supply • 1998 – 1999 Chrysler Corporation President • 1999 – 2000 Daimler Chrysler President • 2000 – 2004 MSX International CEO 2 COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT LLC Forgotten Lessons From Chrysler Fifty years of Ups and Downs • Early success at brand differentiation and loyalty • Product innovation – SUV’s, minivans, features, multipurpose trucks • Low cost, high volume large power trains • International expansion by GM/Ford • Efficiencies of volume and derivatives LESSON: These days are over. 3 COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT LLC Forgotten Lessons From Chrysler Historic Industry Trends • Consolidation through Alliances and Mergers • Insulated and isolated industry mindset • Widespread adversarial