World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chad: the Victims of Hissène Habré Still Awaiting Justice

Human Rights Watch July 2005 Vol. 17, No. 10(A) Chad: The Victims of Hissène Habré Still Awaiting Justice Summary......................................................................................................................................... 1 Principal Recommendations to the Chadian Government..................................................... 2 Historical Background.................................................................................................................. 3 The War against Libya and Internal Conflicts in Chad....................................................... 3 The Regime of Hissène Habré................................................................................................ 4 The Documentation and Security Directorate (DDS) ........................................................ 5 The Crimes of Hissène Habré’s Regime ............................................................................... 8 The Fall of Hissène Habré and the Truth Commission’s Report ................................... 14 The Chadian Association of Victims of Political Repression and Crime....................... 16 Victim Rehabilitation.............................................................................................................. 17 The Prosecution of Hissène Habré...................................................................................... 18 The Victims of Hissène Habré Still Awaiting Justice in Chad .............................................22 Hissène Habré’s Accomplices Still in Positions -

2.3 Chad Road Network

2.3 Chad Road Network National Road Network Rural network Distance Matrix Time Travel Matrix Road Security Weighbridges Axle Load Limits Bridges Road Class Statistics of the existing roads in Chad Surface Conditions Rain Barriers Ouadis (drifts) Page 1 Page 2 For information on Chad Road Network contact details, please see the following link: 4.1 Chad Government Contact List Located in Central Africa at an average altitude of 200 meters, Chad is a large Sahelian country stretching over 2,000 km from north to south and 1,000 km from east to west, covering an area of 1,284 .000 km². Totally landlocked, it shares 5,676 km of borders with 6 bordering countries, including: • 1,055 km to the north with Libya along an almost straight line • 1,360 km to the east with Sudan. • 1,197 km to the south with the Central African Republic. • 889 km to the southwest with Nigeria (89 km of common territorial waterscon Lake Chad) and Cameroon (800 km). • 1,175 km to the west with Niger Chad's road network, both paved and unpaved, is very poorly rarely maintained. According to official road authorities 6000 km of asphalted roads are planned of which a total of 2,086 km are paved and open to the traffic at end of 2014. A 380-km construction project is underway. 4 large asphalting projects planned since 2010 are ongoing and constructions are realized by one Chinese enterprise and Arab Contractor an Egyptian enterprise. Moundou Doba – Koumra (190 km); Massaget – Massakory (72 km) Bokoro – Arboutchatak (65 km); Abeche – Am Himede – Oul Hadjer – Mongo. -

Chapter 1 Present Situation of Chad's Water Development and Management

1 CONTEXT AND DEMOGRAPHY 2 With 7.8 million inhabitants in 2002, spread over an area of 1 284 000 km , Chad is the 25th largest 1 ECOSI survey, 95-96. country in Africa in terms of population and the 5th in terms of total surface area. Chad is one of “Human poverty index”: the poorest countries in the world, with a GNP/inh/year of USD 2200 and 54% of the population proportion of households 1 that cannot financially living below the world poverty threshold . Chad was ranked 155th out of 162 countries in 2001 meet their own needs in according to the UNDP human development index. terms of essential food and other commodities. The mean life expectancy at birth is 45.2 years. For 1000 live births, the infant mortality rate is 118 This is in fact rather a and that for children under 5, 198. In spite of a difficult situation, the trend in these three health “monetary poverty index” as in reality basic indicators appears to have been improving slightly over the past 30 years (in 1970-1975, they were hydraulic infrastructure respectively 39 years, 149/1000 and 252/1000)2. for drinking water (an unquestionably essential In contrast, with an annual population growth rate of nearly 2.5% and insufficient growth in agricultural requirement) is still production, the trend in terms of nutrition (both quantitatively and qualitatively) has been a constant insufficient for 77% of concern. It was believed that 38% of the population suffered from malnutrition in 1996. Only 13 the population of Chad. -

Notes on the Political Sociology of Chad

The Dynamics of National Integration: Ladiba Gondeu Working Paper No. 006 (English Version) THE DYNAMICS OF NATIONAL INTEGRATION: MOVING BEYOND ETHNIC CONFLICT IN A STATE-IN-WAITING LADIBA GONDEU October 2013 The Sahel Research Group, of the University of Florida’s Center for African Studies, is a collaborative effort to understand the political, social, economic, and cultural dynamics of the countries which comprise the West African Sahel. It focuses primarily on the six Francophone countries of the region—Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad—but also on in developments in neighboring countries, to the north and south, whose dy- namics frequently intersect with those of the Sahel. The Sahel Research Group brings together faculty and gradu- ate students from various disciplines at the University of Florida, in collaboration with colleagues from the region. Acknowledgements: This work is the fruit of a four month academic stay at the University of Florida Center for African Studies as a Visiting Scholar thanks to the kind invitation of the Profesor Leonardo A. Villalón, Coordinator of the Sahel Research Group. I would like to express my deep appreciation and gratitude to him and to his team. The ideas put forth in this document are mine and I take full responsibility for them. About the Author: Ladiba Gondeu, Faculty Member in the Department of Anthropology at the University of N’Djamena, and Doctoral Candidate, Paris School of Graduate Studies in Social Science for Social Anthropology and Ethnology. Ladiba Gondeu is a Chadian social anthropologist specializing in civil society, religious dynamics, and project planning and analysis. -

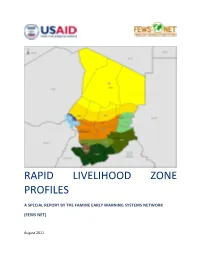

Rapid Livelihood Zone Profiles for Chad

RAPID LIVELIHOOD ZONE PROFILES A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Contents Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 The Uses of the Profiles ............................................................................................................................ 4 Key Concepts ............................................................................................................................................. 5 What is in a Livelihood Profile .................................................................................................................. 7 Methodology ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Rapid Livelihood Zone Profiles for Chad ....................................................................................................... 9 National Overview .................................................................................................................................... 9 Zone 1: South cereals and cash crops ..................................................................................................... 13 Zone 2: Southwest Rice Dominant ......................................................................................................... -

Liste De Contact Humanitaire OCHA Tchad Liste De Contact Humanitaire

Liste de Contact Humanitaire ListeOCHA de Contact Tchad Humanitaire OCHA Tchad Envoyez vos révisions SVP à [email protected]; [email protected] et [email protected] nvoyez vos révisions SVP à [email protected]; [email protected] et [email protected] ©Information Management Unit - OCHA Tchad Juin 2013 Information Management Unit - OCHA Tchad Juillet 2012 ONUSIDA ..................................................................................................... 10 Index UN HABITAT ................................................................................................ 10 UNDSS ......................................................................................................... 10 UNFPA ......................................................................................................... 10 UNHCR ......................................................................................................... 11 1. Autorités de l'Administration Publique .................................................................... 1 PAM ............................................................................................................. 16 CNAR .............................................................................................................. 1 UNHAS (WFP).............................................................................................. 30 CNAR .............................................................................................................. 1 UNECA ........................................................................................................ -

Lutte Contre Le VIH Sida À Moundou Par Le Renforcement De La Réponse Du Centre Djenandoum Naasson

LUTTE CONTRE LE SIDA Lutte contre le VIH sida à Moundou par le renforcement de la réponse du Centre Djenandoum Naasson Prix de la Solidarité Internationale 2007 et Prix Energy Globe Award 2010 et 2011 D'ici à 2015, avoir enrayé la propagation du VIH/ sida et avoir commencé à inverser la tendanceTapez pour saisir le texte actuelle. Assurer à tous ceux qui en ont besoin l'accès aux traitements contre le VIH/sida. Objecf n°6 des "Objecfs du Millénaire pour le Développement" des Naons-Unies. Liste des sigles et abréviaons : ADN Associaon Djénandoum Naasson ARV Anrétroviraux CDN Centre Djénandoum Naasson HRM Hôpital Régional de Moundou IEC Informaon, Éducaon, Communicaon IO Infecon Opportuniste PEC Prise En Charge PVVIH Personne Vivant avec le VIH RTME Réducon de la Transmission de la Mère à l'Enfant VIH Virus de l'Immunodéficience Humaine Prévenon sida, Moundou, Tchad. VIH sida contexte "L'épidémie de sida recule dans le monde. Au Tchad, elle progresse !" Le VIH sida dans le monde Indicateurs du VIH sida dans Nombre de personnes vivant avec le VIH Moins 20% de nouvelles infecons dues le monde Source UNAIDS Nombre de nouvelles infecons au VIH au VIH depuis 10 ans, c'est un signe Nombre de décès dus au sida encourageant ! 33 millions de personnes 4 40 vivant, avec le VIH (PVVIH) en 2009. 2 millions de personnes décèdent du sida 3,5 33,4 chaque année soit 28 millions depuis 32,432,8 31,431,9 30,8 1981, date du premier cas recensé. 70% 30 3 29 30 des personnes infectées vivent en Afrique. -

FEWS Country Report CHAD

Report Number 7 December 1986 FEWS Country Report CHAD Africa Bureau U.S. Agency for International Development MAP 1: CHAD Summary Map LIBYA Bardali N I GE R / (' U A / B.E..T. \ SSub-prefeeture / Fay-Lareau Fighting in contains towns o0 Oct. & Nov. at -risk .. sends civilians o Lto Bilti.ne - / Fadha for relief KAXEM /Sahelian Zone .,,.... harvest complete BII1 TINE AL 30.000 refuuees expected to ,,_f-- 4-by UNHCCH Chad N' DJhmena"- (-.1Sudanian Zone N I G E R I A CHARI- harvest continues Bthrough December N- N LOC2I T JJ OCC I A'ECr C A M E R 0 0 //" LCGONE ORIlElqrIL 70.000 1980 rvtIuree: 20,000 refugees expected A F R I C A IH E P U Li, I C. will require assistance to return in 1987 during 1987 accordine by UNHCR to UNHCR FEWS/PWA, December 1986 Famine Early Warning System Country Report CHAD Good Harvest! Will It Reach Deficit Areas? Prepared for the Africa *Bureau of the U.S. Agency for International Development Prepared by Price, Williams & Associates, Inc. December 1986 Contents Page i Introduction 1 Summary 1 Agriculture 2 Market Conditions 4 Population Movements 6 Food Flows/Needs 6 Populations At-Risk List of Figures 3 Map 2 Market Prices 4 Table I Market Price of Millet 5 Figure I Population Distribution 6 Table 2 Population Distribution 7 Map 3 Populations At-Risk 9 Appendix I Figure 2a Sahclian Zone NVDI Figure 2b Sudanian Zone NVDI Map 4 1986 NVDI vs Average of Good Years 13 Appendix II Table 3 1987 Cereals Back Cover Map 5 Sub-prefectures INTRODUCTION This is the seventh or a series of monthly reports issued by the Famine Early Warning System (FEWS) on Chad. -

47775 World Bank

47775 WORLD BANK Public Disclosure Authorized CHAD TRADE AND TRANSPORT FACILITATION AUDIT 2004 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized JEAN-FRANCOIS ARVIS WORLD BANK INTERNATIONAL TRADE DEPARTMENT Public Disclosure Authorized 1 This report was written following a mission conducted by Mr. Jean-François ARVIS of the World Bank's International Trade Department from May 17-28. The mission was conducted in conjunction with the main mission on the diagnostic study for an integrated trade framework in Chad, coordinated by Messrs. Salomon Samen and Olivier Cadot. Although this report was written as a stand-alone document, it is also a contribution to the chapter on facilitation in the integrated framework report. The mission chose to take an integrated approach to the issue of trade and transport facilitation. To this end, it used the facilitation audit method developed by the World Bank. This approach takes the point of view of international trade stakeholders (importers, exporters, transport operators, freight forwarders) in identifying and quantifying the costs of and obstacles to efficient trade logistics, and then proposes solutions. The study is based mainly on a series of interviews conducted among private sector participants. With regard to the key issue of Chad-bound transit, the mission conducted field surveys on the two main corridors serving Chad, i.e. through Cameroon (Douala corridor) and through Nigeria (Fotokol-Maiduguri corridor). The costs, procedures, and bottlenecks were examined in detail. The study focused primarily on the Douala corridor, which was traveled using various means of transportation through Garoua, Ngaoundere (railway terminal), Yaoundé and Douala in particular. Mr. Faustin Koyasse, senior economist at the World Bank's resident mission in Yaoundé, actively participated in the preparation and implementation of the Cameroon part of the mission. -

Download Report

Document of The World Bank Report No.: 31746 PROJECT PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT REPORT CHAD POPULATION AND AIDS CONTROL PROJECT (CREDIT NO. 2692) March 7, 2005 Sector, Thematic and Global Evaluation Group Operations Evaluation Department Currency Equivalents (annual averages) Currency Unit = FCFA Exchange Rate Effective August Exchange Rate Effective Exchange Rate Effective March 2004 December 31, 2001 1st, 1995 531 CFA Francs = US$1.00 744 CFA Francs = US$1.00 514 CFA Francs = US$1.00 US$0.1883 = 100 CFA Francs US$0.1344 = 100 CFA Francs US$0.1946 = 100 CFA Francs Abbreviations and Acronyms AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency IEC information, education, and Syndrome communication AMASOT Association pour le Marketing KAP knowledge, attitudes, and practices Social au Tchad (Social Marketing KfW Kreditanstalt Für Wiederaufbau Association of Chad M&E monitoring and evaluation ARV anti-retroviral MASACOT Project Social Marketing Unit ASTBEF Association Tchadienne pour le MCH Maternal and child health Bien-Etre Familiale (Chadian MoPC Ministry of Planning and Association for Family Well-being) Cooperation CERPOD Centre de Recherche sur la MoPH Ministry of Public Health Population pour le Développement MTR Mid-term review (Center for Research on Population NGO nongovernmental organization and Development) OED Operations Evaluation Department CNLS Comité National de Lutte contre le PAIP Programme d’Action et SIDA (National AIDS Committee) d’Investissement Prioritaire en CNPRH Commission Nationale de matière de Population (Program for Population et des -

Download File

CHAD COVID-19 Situation Report – #08 [Cumulative update including the period 22 October to 25 November 2020] Situation Overview and Humanitarian Needs As of 25 November 2020, out of the total of 1,661 confirmed COVID-19 cases registered in Chad (the majority being male aged 25-59 years), 26 are children. Of these 26 children, five cases have been confirmed in children under five (four girls and one boy), and 21 cases are children aged between 5 and 14 years (eleven girls and ten boys). Situation52 inCOVID Numbers-19 confirmed cases During this reporting period, COVID-19 reported cases continued to increase particularly in the Southern provinces of Mayo Kebbi-Est/Ouest, Moyen Chari, Logone Occidental and 0% children among the confirmed cases Oriental; overall, the number of reported cases increased at a slower pace than at the beginning of the pandemic. Cases have now been reported in a total of 17 provinces 1,661 COVID-19 2 deaths (representing over three quarters of the country): N’Djaména, Batha, Chari-Baguirmi, confirmed cases Ennedi Est, Guéra, Kanem, Lac, Logone Occidental, Logone Oriental, Mandoul, Mayo 26 children19 recovered among the Kebbi-Est, Mayo Kebbi-Ouest, Moyen-Chari, Ouaddaï, Sila, Tandjilé and Wadi-Fira. As of confirmed cases 25 November 2020, 64 cases are hospitalized and under treatment, 1,496 patients have recovered, and 101 deaths are attributable to COVID-19; a total of 233 out of 243 (97 per 101 deaths cent) contacts have been traced and are followed1. 1,496 recovered Following the reopening of the N’Djaména international airport on 1 August and the easing of travel restrictions in-country as well as the public transportation and markets, the number of reported COVID-19 cases has steadily increased since beginning of October. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 1 II. PERSISTENCE OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS BY THE CHADIAN GOVERNMENT AND THE SECURITY FORCES ........................................ 3 A. Arbitrary arrests ..................................................................................... 3 B. Torture and ill-treatment ....................................................................... 8 C. Deaths in detention as a result of torture ............................................ 13 D. Extrajudicial executions and "disappearances" ............................... 17 E. The death penalty .................................................................................. 22 III. THE VICTIMS .................................................................................................. 22 A. Violence against women ........................................................................ 22 B. Attacks on human rights defenders, journalists and others .............. 25 IV. CHADIAN AND INTERNATIONAL RESPONSIBILITY ........................... 27 A. The security forces ................................................................................ 27 B. International responsibility .................................................................. 31 1. France ........................................................................................ 32 2. China .......................................................................................... 37 3. The