Defining the Mesozoic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dinosaur Wars Program Transcript

Page 1 Dinosaur Wars Program Transcript Narrator: For more than a century, Americans have had a love affair with dinosaurs. Extinct for millions of years, they were barely known until giant, fossil bones were discovered in the mid-nineteenth century. Two American scientists, Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh, led the way to many of these discoveries, at the forefront of the young field of paleontology. Jacques Gauthier, Paleontologist: Every iconic dinosaur every kid grows up with, apatosaurus, triceratops, stegosaurus, allosaurus, these guys went out into the American West and they found that stuff. Narrator: Cope and Marsh shed light on the deep past in a way no one had ever been able to do before. They unearthed more than 130 dinosaur species and some of the first fossil evidence supporting Darwin’s new theory of evolution. Mark Jaffe, Writer: Unfortunately there was a more sordid element, too, which was their insatiable hatred for each other, which often just baffled and exasperated everyone around them. Peter Dodson, Paleontologist: They began life as friends. Then things unraveled… and unraveled in quite a spectacular way. Narrator: Cope and Marsh locked horns for decades, in one of the most bitter scientific rivalries in American history. Constantly vying for leadership in their young field, they competed ruthlessly to secure gigantic bones in the American West. They put American science on the world stage and nearly destroyed one another in the process. Page 2 In the summer of 1868, a small group of scientists boarded a Union Pacific train for a sightseeing excursion through the heart of the newly-opened American West. -

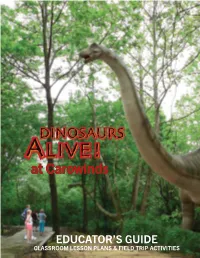

At Carowinds

at Carowinds EDUCATOR’S GUIDE CLASSROOM LESSON PLANS & FIELD TRIP ACTIVITIES Table of Contents at Carowinds Introduction The Field Trip ................................... 2 The Educator’s Guide ....................... 3 Field Trip Activity .................................. 4 Lesson Plans Lesson 1: Form and Function ........... 6 Lesson 2: Dinosaur Detectives ....... 10 Lesson 3: Mesozoic Math .............. 14 Lesson 4: Fossil Stories.................. 22 Games & Puzzles Crossword Puzzles ......................... 29 Logic Puzzles ................................. 32 Word Searches ............................... 37 Answer Keys ...................................... 39 Additional Resources © 2012 Dinosaurs Unearthed Recommended Reading ................. 44 All rights reserved. Except for educational fair use, no portion of this guide may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any Dinosaur Data ................................ 45 means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other without Discovering Dinosaurs .................... 52 explicit prior permission from Dinosaurs Unearthed. Multiple copies may only be made by or for the teacher for class use. Glossary .............................................. 54 Content co-created by TurnKey Education, Inc. and Dinosaurs Unearthed, 2012 Standards www.turnkeyeducation.net www.dinosaursunearthed.com Curriculum Standards .................... 59 Introduction The Field Trip From the time of the first exhibition unveiled in 1854 at the Crystal -

A Phylogenetic Analysis of the Basal Ornithischia (Reptilia, Dinosauria)

A PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE BASAL ORNITHISCHIA (REPTILIA, DINOSAURIA) Marc Richard Spencer A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December 2007 Committee: Margaret M. Yacobucci, Advisor Don C. Steinker Daniel M. Pavuk © 2007 Marc Richard Spencer All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Margaret M. Yacobucci, Advisor The placement of Lesothosaurus diagnosticus and the Heterodontosauridae within the Ornithischia has been problematic. Historically, Lesothosaurus has been regarded as a basal ornithischian dinosaur, the sister taxon to the Genasauria. Recent phylogenetic analyses, however, have placed Lesothosaurus as a more derived ornithischian within the Genasauria. The Fabrosauridae, of which Lesothosaurus was considered a member, has never been phylogenetically corroborated and has been considered a paraphyletic assemblage. Prior to recent phylogenetic analyses, the problematic Heterodontosauridae was placed within the Ornithopoda as the sister taxon to the Euornithopoda. The heterodontosaurids have also been considered as the basal member of the Cerapoda (Ornithopoda + Marginocephalia), the sister taxon to the Marginocephalia, and as the sister taxon to the Genasauria. To reevaluate the placement of these taxa, along with other basal ornithischians and more derived subclades, a phylogenetic analysis of 19 taxonomic units, including two outgroup taxa, was performed. Analysis of 97 characters and their associated character states culled, modified, and/or rescored from published literature based on published descriptions, produced four most parsimonious trees. Consistency and retention indices were calculated and a bootstrap analysis was performed to determine the relative support for the resultant phylogeny. The Ornithischia was recovered with Pisanosaurus as its basalmost member. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2017 Fossil Excavation, Museums, and Wyoming: American Paleontology, 1870-1915 Marlena Briane Cameron Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES FOSSIL EXCAVATION, MUSEUMS, AND WYOMING: AMERICAN PALEONTOLOGY, 1870-1915 By MARLENA BRIANE CAMERON A Thesis submitted to the Program in the History and Philosophy of Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2017 Marlena Cameron defended this thesis on July 17, 2017. The members of the supervisory committee were: Ronald E. Doel Professor Directing Thesis Michael Ruse Committee Member Kristina Buhrman Committee Member Sandra Varry Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ iv Abstract ............................................................................................................................................v 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................1 2. THE BONE WARS ....................................................................................................................9 -

George P. Merrill Collection, Circa 1800-1930 and Undated

George P. Merrill Collection, circa 1800-1930 and undated Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 1 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: PHOTOGRAPHS, CORRESPONDENCE AND RELATED MATERIAL CONCERNING INDIVIDUAL GEOLOGISTS AND SCIENTISTS, CIRCA 1800-1920................................................................................................................. 4 Series 2: PHOTOGRAPHS OF GROUPS OF GEOLOGISTS, SCIENTISTS AND SMITHSONIAN STAFF, CIRCA 1860-1930........................................................... 30 Series 3: PHOTOGRAPHS OF THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL SURVEY OF THE TERRITORIES (HAYDEN SURVEYS), CIRCA 1871-1877.............................................................................................................. -

The Fighting Pair

THE FIGHTING PAIR ALLOSAURUS VS STEGOSAURUS — Allosaurus “jimmadsoni” and Hesperosaurus (Stegosaurus) mjosi Upper Jurassic Period, Kimmeridgian Stage, 155 million years old Morrison Formation Dana Quarry, Ten Sleep, Washakie County, Wyoming, USA. THE ALLOSAURUS The Official State Fossil of Utah, the Allosaurus was a large theropod carnosaur of the “bird-hipped” Saurischia order that flourished primarily in North America during the Upper Jurassic Period, 155-145 million years In the spring of 2007, at the newly-investigated Dana Quarry in the Morrison Formation of Wyoming, the team from ago. Long recognized in popular culture, it bears the distinction of being Dinosauria International LLC made an exciting discovery: the beautifully preserved femur of the giant carnivorous one of the first dinosaurs to be depicted on the silver screen, the apex Allosaur. As they kept digging, their excitement grew greater; next came toe bones, leg bones, ribs, vertebrae and predator of the 1912 novel and 1925 cinema adaptation of Conan Doyle’s finally a skull: complete, undistorted and, remarkably, with full dentition. It was an incredible find; one of the most The Lost World. classic dinosaurs, virtually complete, articulated and in beautiful condition. But that was not all. When the team got The Allosaurus possessed a large head on a short neck, a broad rib-cage the field jackets back to the preparation lab, they discovered another leg bone beneath the Allosaurus skull… There creating a barrel chest, small three-fingered forelimbs, large powerful hind limbs with hoof-like feet, and a long heavy tail to act as a counter-balance. was another dinosaur in the 150 million year-old rock. -

The Dinosaurs of North America

FEOM THE SIXTEENTH ANNUAL KEPOKT OF THE U. S, GEOLOGICAL SURVEY THE DINOSAURS OF NORTH AMERICA OTHNIEL CHARLES MARSH TALE UNIVERSITY WASHINGTON 1896 ^33/^, I/BRAKt 4 ,\ . THE DINOSAURS OF NORTH AMERICA. BY OTHNIEL CHARLES MARSH. 133 CONTENTS. Pajje. Introduction 143 Part I. —Triassic dinosaurs 146 Theropoda 146 Anchisaurida? 147 Anchisaurus 147 The skull 148 The fore limbs 149 The hind limbs 149 Anchisaurus solus 149 Amniosaurus rTT 150 Eestoration of Anchisaurus 150 Dinosaurian footprints 151 Distribution of Triassic dinosaurs 152 Part II. —Jurassic dinosaurs 152 Theropoda : 153 Hallopus 153 Fore and hind limbs 154 Coelurus _ 155 The vertebra:- 155 The hind limbs 156 Ceratosaurus 156 The skull 157 The brain 159 The lower iaws 159 The vertebra: 159 The scapular arch 160 The pelvic arch 160 The metatarsals 162 Eestoration of Ceratosaurus 163 Allosaurus 163 European Theropoda 163 Sauropoda 164 Atlantosaurus beds 164 Families of Sauropoda 165 Atlantosauridie 166 Atlantosaurus 166 Apatosaurus 166 The sacral cavity 166 The vertebra- 167 Brontosaurus 168 The scapular arch 168 The cervical vertebra.- 169 The dorsal vertebree 169 The sacrum 170 The caudal vertebra- 171 The pelric arch 172 The fore limbs 173 The hind limbs 173 135 136 CONTENTS. Part II. —Jurassic dinosaurs—Continued. Page. Sauropoda—Continued. Atlantosaurida? —Continued. Restoration of Brontosaurus 173 Barnsaurus 174 Diplodoeida? 175 Diplodocus 175 The skull 175 The brain 178 The lower jaws 178 The teeth 179 The vertebra; 180 The sternal bones 180 The pelvic girdle 180 Size and habits 180 Morosaurida? 181 Morosaurus 181 The skull 181 The vertebra? 181 The fore limbs 182 The pelvis 182 The hind limbs 183 Pleuroccelida? : 183 Pleurocoelus 183 The skull 183 The vertebras 183 Distribution of the Sauropoda 185 Comparison with European forms 185 Predentata ». -

Lyons SCIENCE 2021 the Influence of Juvenile Dinosaurs SUPPL.Pdf

science.sciencemag.org/content/371/6532/941/suppl/DC1 Supplementary Materials for The influence of juvenile dinosaurs on community structure and diversity Katlin Schroeder*, S. Kathleen Lyons, Felisa A. Smith *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Published 26 February 2021, Science 371, 941 (2021) DOI: 10.1126/science.abd9220 This PDF file includes: Materials and Methods Supplementary Text Figs. S1 and S2 Tables S1 to S7 References Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following: (available at science.sciencemag.org/content/371/6532/941/suppl/DC1) MDAR Reproducibility Checklist (PDF) Materials and Methods Data Dinosaur assemblages were identified by downloading all vertebrate occurrences known to species or genus level between 200Ma and 65MA from the Paleobiology Database (PaleoDB 30 https://paleobiodb.org/#/ download 6 August, 2018). Using associated depositional environment and taxonomic information, the vertebrate database was limited to only terrestrial organisms, excluding amphibians, pseudosuchians, champsosaurs and ichnotaxa. Taxa present in formations were confirmed against the most recent available literature, as of November, 2020. Synonymous taxa or otherwise duplicated taxa were removed. Taxa that could not be identified to genus level 35 were included as “Taxon X”. GPS locality data for all formations between 200MA and 65MA was downloaded from PaleoDB to create a minimally convex polygon for each possible formation. Any attempt to recreate local assemblages must include all potentially interacting species, while excluding those that would have been separated by either space or time. We argue it is 40 acceptable to substitute formation for home range in the case of non-avian dinosaurs, as range increases with body size. -

Lakamie Basin, Wyoming

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, DIRECTOR BULLETIN 364 GEOLOGY AND MINERAL RESOURCES OF THE LAKAMIE BASIN, WYOMING A PRELIMINARY REPORT BY N. H. DARTON AND C. E. SIEBENTHAL WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1909 CONTENTS. Page. Introduction............................................................. 7 Geography ............................................................... 8 Configuration........................................................ 8 Drainage ............................................................ 9 Climate ............................................................. 9 Temperature...................................................... 9 Precipitation..................................................... 10 Geology ................................................................. 11 Stratigraphy.......................................................... 11 General relations........................../....................... .11 Carboniferous system............................................. 13 Casper formation......................... .................... 13. General character........................................ 13 Thickness ............................................... 13 Local features............................................ 14 Erosion and weathering of limestone slopes ................ 18 Paleontology and age..................................... 19 Correlation .............................................. 20 Forelle limestone............................................ -

The Rio Chama: a River Guide to the Geology and Landscapes

ALLOSAURUS — FOOTPRINTS IN DEEP TIME Because New Mexico contains a well-exposed, nearly complete record of the geologic formations through time (stretching back over 500 million years of the a roadrunner, and considerably faster than an Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic Eras), the state average human. Allosaurus was capable of kill- has a phenomenally rich fossil record. The many ing healthy, medium-sized sauropods (long- local discoveries of dinosaurs, prehistoric reptiles, necked herbivores), and they may have and extinct mammals include one of the earliest hunted in packs. dinosaurs, many of the planet’s fiercest preda- Allosaurus was among the earli- tors, some of the largest animals to ever walk, est dinosaur discoveries, and its fossils and bizarre giant reptiles and birds. Due to its are abundant. It was first unearthed in outstanding exposures of Mesozoic rocks that Colorado in 1877, and named by Yale paleontolo- represent ancient river systems where creatures gist Othniel Charles Marsh. The name Allosaurus would congregate for food and water, the Rio Chama is derived from the Greek “allos" (different) and watershed is a hub of dinosaur discovery. “sauros” (lizard), so-named because its vertebrae At the top of the Jurassic food chain was the differed from other known dinosaurs. Although theropod dinosaur Allosaurus, the largest land-based Marsh’s specimen consisted of only a few fragments of predator of the time. Allosaurus reigned supreme for the dinosaur, many more were later collected, and in 5 million years, from 155.7 to 150.8 million years ago. 1991, a Wyoming team unearthed "Big Al” which was Although smaller than T. -

Body-Size Evolution in the Dinosauria

8 Body-Size Evolution in the Dinosauria Matthew T. Carrano Introduction The evolution of body size and its influence on organismal biology have received scientific attention since the earliest decades of evolutionary study (e.g., Cope, 1887, 1896; Thompson, 1917). Both paleontologists and neontologists have attempted to determine correlations between body size and numerous aspects of life history, with the ultimate goal of docu- menting both the predictive and causal connections involved (LaBarbera, 1986, 1989). These studies have generated an appreciation for the thor- oughgoing interrelationships between body size and nearly every sig- nificant facet of organismal biology, including metabolism (Lindstedt & Calder, 1981; Schmidt-Nielsen, 1984; McNab, 1989), population ecology (Damuth, 1981; Juanes, 1986; Gittleman & Purvis, 1998), locomotion (Mc- Mahon, 1975; Biewener, 1989; Alexander, 1996), and reproduction (Alex- ander, 1996). An enduring focus of these studies has been Cope’s Rule, the notion that body size tends to increase over time within lineages (Kurtén, 1953; Stanley, 1973; Polly, 1998). Such an observation has been made regarding many different clades but has been examined specifically in only a few (MacFadden, 1986; Arnold et al., 1995; Jablonski, 1996, 1997; Trammer & Kaim, 1997, 1999; Alroy, 1998). The discordant results of such analyses have underscored two points: (1) Cope’s Rule does not apply universally to all groups; and (2) even when present, size increases in different clades may reflect very different underlying processes. Thus, the question, “does Cope’s Rule exist?” is better parsed into two questions: “to which groups does Cope’s Rule apply?” and “what process is responsible for it in each?” Several recent works (McShea, 1994, 2000; Jablonski, 1997; Alroy, 1998, 2000a, 2000b) have begun to address these more specific questions, attempting to quantify patterns of body-size evolution in a phylogenetic (rather than strictly temporal) context, as well as developing methods for interpreting the resultant patterns. -

Lesothosaurus, "Fabrosaurids," and the Early Evolution of Ornithischia Author(S): Paul C

Lesothosaurus, "Fabrosaurids," and the Early Evolution of Ornithischia Author(s): Paul C. Sereno Source: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Vol. 11, No. 2 (Jun. 20, 1991), pp. 168-197 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. on behalf of The Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4523370 Accessed: 28-01-2019 13:42 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, Taylor & Francis, Ltd. are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology This content downloaded from 69.80.65.67 on Mon, 28 Jan 2019 13:42:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 11(2): 168-197, June 1991 © 1991 by the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology LESOTHOSAURUS, "FABROSAURIDS," AND THE EARLY EVOLUTION OF ORNITHISCHIA PAUL C. SERENO Department of Organismal Biology and Anatomy, University of Chicago, 1025 E. 57th Street, Chicago, Illinois 60637 ABSTRACT -New materials of Lesothosaurus diagnosticus permit a detailed understanding of one of the earliest and most primitive ornithischians. Skull proportions and sutural relations can be discerned from several articulated and disarticulated skulls. The snout is proportionately long with a vascularized, horn-covered tip.