Volledige Tekst FINAL Paredis Juni 2013 85

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compte Rendu Analytique Beknopt Verslag

CRABV 53 PLEN 003 CRABV 53 PLEN 003 CHAMBRE DES REPRESENTANTS BELGISCHE KAMER VAN DE BELGIQUE VOLKSVERTEGENWOORDIGERS COMPTE RENDU ANALYTIQUE BEKNOPT VERSLAG SÉANCE PLÉNIÈRE PLENUMVERGADERING Mardi Dinsdag 12-10-2010 12-10-2010 Après-midi Namiddag CHAMBRE-2E SESSION DE LA 53E LEGISLATURE 2010 2011 KAMER-2E ZITTING VAN DE 53E ZITTINGSPERIODE CRABV 53 PLEN 003 12/10/2010 i SOMMAIRE INHOUD EXCUSÉS 1 BERICHTEN VAN VERHINDERING 1 Ouverture de la session ordinaire 2010-2011 1 Opening van de gewone zitting 2010-2011 1 Nomination du Bureau définitif 1 Benoeming van het Vast Bureau 1 Nomination du président 2 Benoeming van de voorzitter 2 Orateurs: Thierry Giet, président du groupe Sprekers: Thierry Giet, voorzitter van de PS- PS fractie Nomination des vice-présidents et des secrétaires 2 Benoeming van de ondervoorzitters en van de 2 secretarissen Orateurs: Thierry Giet, président du groupe Sprekers: Thierry Giet, voorzitter van de PS- PS fractie Allocution de M. le Président 2 Toespraak van de voorzitter 2 Éloge funèbre de M. Daniel Ducarme, ministre 4 Rouwhulde – de heer Daniel Ducarme, minister 4 d'État van staat Orateurs: Yves Leterme, premier ministre Sprekers: Yves Leterme, eerste minister Éloge funèbre de M. Albert Claes 7 Rouwhulde voor de heer Albert Claes 7 Orateurs: Yves Leterme, premier ministre Sprekers: Yves Leterme, eerste minister Éloge funèbre de M. André Lagasse 8 Rouwhulde – de heer André Lagasse 8 Orateurs: Yves Leterme, premier ministre Sprekers: Yves Leterme, eerste minister Application de l'article 147 du Règlement de la -

Ihf Report 2006 Human Rights in the Osce Region 76 Belgium

74 BELGIUM* IHF FOCUS: anti-terrorism measures; freedom of expression, free media and infor- mation; freedom of religion and religious tolerance; national minorities; racism, in- tolerance and xenophobia; migrants, asylum seekers and refugees. The main human rights concerns in New anti-terrorism legislation adopted Belgium in 2005 were racial discrimination during the year broadened the powers of and intolerance and violations of the rights police and public prosecutors to engage in of asylum seekers and immigrants. surveillance and control, which gave rise to In May, Belgium signed Protocol No. 7 concern about violations of privacy rights to the Council of Europe Convention for and freedom of expression. the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR), which ex- Anti-Terrorism Measures1 tends the list of protected rights to include On 28 October, the Council of Minis- the right of aliens to procedural guarantees ters submitted to the Chamber of Repre- in the event of expulsion from the territory sentatives a draft law that envisaged chan- of a state; the right of a person convicted ges to the criminal code and judicial code of a criminal offence to have the sentence concerning special forms of investigation reviewed by a higher tribunal; the right to in the fight against terrorism and organized compensation in the event of a miscar- crime.2 New legislation on this topic was riage of justice; the right not to be tried or necessary because the Court of Arbitration punished for an offence for which one has partially revoked existing legislation in a already been acquitted or convicted; as decision of 21 December 2004. -

'À Peu Près Chaque Fonds Privé Constitue Un Problème Nouveau' 1

80 / Sofie Vrielynck, Archief, Amsab-ISG ‘À peu près chaque fonds privé constitue un problème nouveau’ 1 Archieven van personen zijn niet de meest evidente om te verwerken. Geen enkel persoonlijk archief lijkt op een ander, keer op keer is de verwerking en het con- textueel toegankelijk maken van het archief een nieuwe uitdaging. In eerste instantie wordt informatie ingewonnen over de archiefvormer, hoe zijn leven en loopbaan er tot op het afgeven van zijn archief uitzag. Die informa- tie kan je vinden bij de archiefvormer zelf of bij nabestaanden, let wel op voor enige subjectiviteit. Daarom is het ook aangeraden om literatuur te raadplegen en het internet af te schuimen. Voor de latere inventarisatie – in het bijzonder voor het opmaken van het archiefschema en de ordening – is het onderzoek naar de levensloop van een persoon van cruciaal belang. Het resultaat van het biografisch onderzoek wordt neergeschreven in een concept voor een archiefschema waarin per fase of functie een systematische opsomming wordt gegeven van alle hande- lingen en activiteiten.2 Ook moet een archiefschema zo opgebouwd zijn dat het archief transparant is voor de archiefvormer, zijn of haar nabestaanden, de on- derzoeker, de belangstellende … Het spreekt vanzelf dat het voorlopige archiefschema nog moet getoetst worden aan het concrete archiefmateriaal. Voor de aanvang van de verwerking dient men na te gaan hoe het archief tot stand is gekomen en hoe het werd beheerd. Idealiter staat een geordend archief voorop en komt het erop neer de ‘oude’ orde te hand- haven bij de verwerking van het archief. Voor persoonlijke archieven klinkt dit utopisch, want ze vertonen zelden een efficiënte en systematische ordening. -

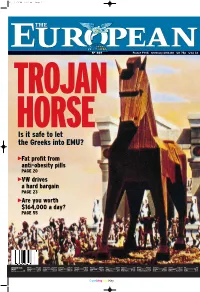

Is It Safe to Let the Greeks Into EMU?

01 21/3/98 3:13 pm Page 1 No 409 France Ffr15 Germany DM3.80 UK 75p USA $3 TROJAN HORSE Is it safe to let the Greeks into EMU? ▼ Fat profit from anti-obesity pills PAGE 20 VW drives a hard bargain PAGE 23 ▼▼ Are you worth $164,000 a day? PAGE 55 INTERNATIONAL Bahrain...........Din1.650 Canary Isles ....Ptas400 Denmark ..........Kr18.00 Germany ..........DM3.80 Hungary ..........HUF340 Italy..................L4,000 Malaysia.................S$7 Norway............Kr20.00 Singapore...............S$7 Sweden............Kr20.00 UK .........................75p PRICES Belgium ................Bf75 Croatia ...........KN22.00 Finland............Mk15.00 Gibraltar..............£1.40 Ireland (Rep).......IR£1.00 Japan ..................Y700 Malta ................Ml0.80 Poland.................Zl 7.9 Slovenia ............Sit450 Switzerland.........F4.00 USA ....................$3.00 Austria...................S35 Canada .............C$3.50 Cyprus...............C£1.20 France.............Ffr15.00 Greece................Dr500 Israel...................NS 12 Luxembourg ..........Lf75 Netherlands ......Fl 4.00 Portugal(Cont.)Esc 430 Spain...............Ptas375 Turkey.........TL350,000 USAFE .................$1.95 CyanMagYelloKey CONTENTS EPA COVER STORY Greece on the tracks 8 Shuttle diplomacy and a timely devaluation have put the drachma on course for the euro, but can even radical reform rescue the Greek economy? INSIDER EMU’s interest rate fault lines 6 Europe’s economies are not clocks, all ticking to the same interest rates NEWS Dining with the enemy 14 France’s -

Een Onderzoek Naar Vlaamse Schijnverkozenen (1994-2007)

UNIVERSITEIT GENT FACULTEIT POLITIEKE EN SOCIALE WETENSCHAPPEN ’Alle hens aan dek’: een onderzoek naar Vlaamse schijnverkozenen (1994-2007) Wetenschappelijke verhandeling Aantal woorden: 24.999 FREDERIK SCHEERLINCK MASTERPROEF POLITIEKE WETENSCHAPPEN afstudeerrichting NATIONALE POLITIEK PROMOTOR: (PROF.) DR. HERWIG REYNAERT COMMISSARIS: (PROF.) DR. KRISTOF STEYVERS COMMISSARIS: LIC. HILDE VAN LIEFFERINGE ACADEMIEJAAR 2008 - 2009 Inzagerecht in de masterproef (*) Ondergetekende, ……………………………………………………. geeft hierbij toelating / geen toelating (**) aan derden, niet- behorend tot de examencommissie, om zijn/haar (**) proefschrift in te zien. Datum en handtekening ………………………….. …………………………. Deze toelating geeft aan derden tevens het recht om delen uit de scriptie/ masterproef te reproduceren of te citeren, uiteraard mits correcte bronvermelding. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- (*) Deze ondertekende toelating wordt in zoveel exemplaren opgemaakt als het aantal exemplaren van de scriptie/masterproef die moet worden ingediend. Het blad moet ingebonden worden samen met de scriptie onmiddellijk na de kaft. (**) schrappen wat niet past ________________________________________________________________________________________ Dankwoord Graag zou ik eerst nog enkele mensen willen bedanken. Laat me beginnen met mijn promotor, prof. dr. Herwig Reynaert. Op het moment dat ik niet meer goed wist wat ik in mijn onderzoek allemaal wou behandelen, was hij er om me in een bepaalde richting te sturen. Daarnaast -

Plenumvergadering Séance Plénière

CRABV 52 PLEN 020 14/02/2008 1 PLENUMVERGADERING SÉANCE PLÉNIÈRE van du DONDERDAG 14 FEBRUARI 2008 JEUDI 14 FÉVRIER 2008 Namiddag Après-midi ______ ______ De vergadering wordt geopend om 14.20 uur en voorgezeten door de heer Herman Van Rompuy. Aanwezig bij de opening van de vergadering zijn de ministers van de federale regering: mevrouw Sabine Laruelle en de heren Guy Verhofstadt, Patrick Dewael en Jo Vandeurzen Een reeks mededelingen en besluiten moeten ter kennis gebracht worden van de Kamer. Zij worden op de website van de Kamer en in de bijlage bij het integraal verslag van deze vergadering opgenomen. Berichten van verhindering Ambtsplicht: Juliette Boulet en Yvan Mayeur Gezondheidsredenen: Patrick Moriau Federale regering Yves Leterme, vice-eersteminister en minister van Begroting, Mobiliteit en Institutionele Hervormingen: gezondheidsredenen Karel De Gucht, minister van Buitenlandse Zaken: met zending buitenslands Josly Piette, minister van Werk: met zending Vragen 01 Vraag van de heer Peter Vanvelthoven aan de eerste minister over "de koopkracht van de Belgische bevolking". (nr. P0080) 01.01 Peter Vanvelthoven (sp.a-spirit): De uitspraken van diverse organisaties, zoals Unizo, Voka en VBO, en van de Nationale Bank met betrekking tot de koopkracht van de Belgische bevolking tarten werkelijk alle verbeelding: zij beweren namelijk dat er geen sprake is geweest van een koopkrachtprobleem in de afgelopen twee jaar. Zij verliezen daarbij natuurlijk de huidige levensduurte uit het oog, aangezien de energieprijzen net nu fors gestegen zijn en de inflatie zich op het hoogste peil in zestien jaar bevindt. Dit zijn dus toch wel vrij onbehoorlijke uitspraken die bovendien haaks staan op wat de premier verkondigde in zijn regeringsverklaring, waar hij het had over het intomen van prijsstijgingen die knagen aan het gezinsbudget en het verminderen van de facturen voor lage en gemiddelde inkomens. -

Focus on the DUTCH SPEAKING PART of BELGIUM Press Review Weekly, Does Not Appear in July • Number 28 • 3 July - 9 July

flandersfocus on THE DUTCH SPEAKING PART OF BELGIUM press review weekly, does not appear in July • number 28 • 3 July - 9 July INTRODUCTION la fland Is Louis Michel fleeing to ur re s • s f ne thing is certain: there u o c c o u will be no new Flemish Gov- f s O • o n ernment by the Flemish nation- n Europe? r f e l a d al holiday on 11 July. Yves n n d a l e f Leterme, who is leading the ne- r f s u a • f o s k u gotiations on the formation of a hings have not been going well re- Foreign Affairs Louis Michel, is in turn new government, is aiming for T cently for the Mouvement Réfor- considering moving to the European 20 July. On 7 July the sticking points that technical mateur (MR). Several weeks ago the Commission. PS Chairman Elio Di working groups had studied over the past week were listed. De Standaard (8 July) summarises the party learned that it was being dumped Rupo is apparently prepared to offer key ones: tax cuts, for which the VLD is pressing, by the PS in all regional governments. him the commissionership of PS mem- building land policy, healthcare premiums, the ex- And recently there was also little com- ber Philippe Busquin in exchange for pansion of (free) bus and tram travel, direct elec- tions for mayors and obviously the budget, and forting news for the party from the Fed- chairmanship of the Chamber or Senate more specifically the surplus that must be aimed for: eral Government. -

The Determinants of Balanced Coverage of Political News Sources in Television News

1 Faculteit Politieke en Sociale Wetenschappen Departement Politieke Wetenschappen Proefschrift voorgelegd tot het behalen van de graad van Doctor in de Sociale Wetenschappen: Politieke Wetenschappen aan de Universiteit Antwerpen te verdedigen door Knut De Swert Where is the balance in the news? The determinants of balanced coverage of political news sources in television news. Nederlandse titel: Waar is het evenwicht in het nieuws? Determinanten van balans tussen politieke actoren in het televisienieuws 2 3 Abstract The basic idea of this Ph.D. study is to use the concept of balance to make it possible to study media bias at news item level, offering the great advantage that news item specific characteristics can be brought into explanatory analyses on media bias. First, the study of the use of political actors in the news is situated in the wider field of media research. Then, some of the basic concepts of the debate on this subject are presented in the large framework of the media bias literature. At the end of this chapter, balance will be chosen as the specific concept to work with, since this can be measured at the news item level. After specifying the exact way this concept will be used in the framework of this Ph.D., and after validating of this concept, existing literature is discussed that can be helpful in the quest for determinants of balance on different levels of the news making process. These determinants will be evaluated on the country level, the broadcaster level, the journalist level and the item level. Two empirical chapters follow upon this, one based on Flemish ENA-data (2003-2007) and one based on a self-collected international sample of 24 newscasts of eleven countries. -

Optimization Issues in Machine Learning of Coreference Resolution

Universiteit Antwerpen Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte Optimization Issues in Machine Learning of Coreference Resolution Optimalisatie van Lerende Technieken voor Coreferentieresolutie Proefschrift voorgelegd tot het behalen van de graad van doctor in de Taal- en letterkunde aan de Universiteit Antwerpen te verdedigen door V´eronique HOSTE Promotor: Prof. Dr. W. Daelemans Antwerpen, 2005 c Copyright 2005 - V´eronique Hoste (University of Antwerp) No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means without written permission from the author. Cokverakbased on painting \T,JI" from Gun¨ ter Tuzina Scientific knowledge always remains sheer guesswork - although kak guesswork controlled by criticism and experiment. -Karl Popper -Realism and the Aim of Science, p. 13 kakIf you knew some of the experiments (if they may be so-called) which I am trying, you would have a good right to sneer, for they are so absurd even in my opinion that I dare not tell you. -Charles Darwin -Letter to J.D. Hooker, April 14th, 1855 Abstract This thesis presents a machine learning approach to the resolution of coreferen- tial relations between nominal constituents in Dutch. It is the first automatic resolution approach proposed for this language. The corpus-based strategy was enabled by the annotation of a substantial corpus (ca. 12,500 noun phrases) of Dutch news magazine text with coreferential links for pronominal, proper noun and common noun coreferences. Based on the hypothesis that different types of information sources contribute to a correct resolution of different types of coreferential links, we propose a modular approach in which a separate module is trained per NP type. -

Belgian Polities in 2000

Belgian Polities in 2000 Stefaan Fiers Postdoctoral Fellow of the Fund for Scientific Research-Flanders at the Section of Politica/ Sociology of the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven Mark Deweerdt Politica! Journalist of De Financieel-Economische Tijd Summary In the course of the year 2000, the cabinet of Prime Minister Verhofstadt focused on some major projects that had been announced in the governmental agreement of July 1999: the reduction of income taxes, the establishment of a Silverfund to counter the casts of the ageing of the population, the modernisation of the civil service and the development of a National Security Plan. The coalition parties, backed by the Volksunie, also made their way with difficulty through yet another step in the reform of the State. Like in 1999, the aftermath of the dioxin-crisis and the policy on asylum were high on the agenda in 2000 toa. In particular the regularisation of the stay of 50.000 illegal residents, was problematic. In two dossiers on mobility, the ban on night flights to Zaventem airport and the reorganisation of the national railway company NMBS-SNCB, a conflict arose between the green and liberal parties, and between Prime Minister Verhofstadt and minister for Mobility Durant in particular. The /ocal and provincial elections of October 8th, 2000 did not have any effect on the functioning of the government. 1. The budgetary policy A. Budgetary Results for 1999 and contra/ of the 2000-budget On January 5th, the federal ministers for Budget, Johan Vande Lanotte, and for Finances, Didier Reynders, announced that the deficit of the government had been reduced to 0,9 % of GDP. -

Programme Governmental Days

Global Forum on Migration and Development First Meeting Belgium, 9-11 July 2007 Programme and Agenda Dear participants, On behalf of the Government of Belgium, we would like to welcome you in Brussels for the first meeting of the Global Forum on Migration and Development (GFMD). Since the High Level Dialogue on International Migration and Development held in New York last September, we have been meeting regularly with you, or your representatives, to build this new process and define the themes that will be addressed during this meeting. We are all aware that the close relation between migration and development needs to be addressed pro-actively in order to meet the challenges this complex relationship poses and to benefit from the opportunities it offers. Bilateral and regional initiatives, political statements and research have been stressing this need during the last decade. It is now time for governments to act together at the global level and to consider how migration can contribute to development, but also to analyse what development can do to prevent people from migrating by necessity. We hope that these two days will offer you the opportunity to meet with other delegates in an informal and interactive dialogue, enabling you to leave Brussels with innovative ideas, projects or partnerships related to the different issues that will be addressed during the roundtable sessions. At each roundtable session that will be held during these two days, we invite you to work together with other government delegates, and to reflect upon proposals for action-oriented outcomes that could be pursued voluntarily through concrete follow up to enhance the mutual benefits of migration and development. -

Migration and Development Conference Migration and Development Conference

Migration and Development Conference and Development Migration Migration and Development Conference March 2006,Brussels Prepared by: Final Report The International Organization for Migration (IOM) Regional Liaison and Coordination Office to the European Union Rue Montoyer 40, 1000 Brussels, Phone: 32 2 282 45 60, Fax: 32 2 230 07 63 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.belgium.iom.int/internationalconference A joint initiative: March 2006 March The Goverment of the Kingdom of Belgium The International Organization for Migration (IOM) The European Commission The World Bank Conference on migration and development 15/16 March 2006, Brussels CONFERENCE REPORT BELGIUM The World Bank Acknowledgements The Conference on Migration and Development, held on the 15 and 16 March 2006 in Brussels was an important and groundbreaking event organized by the Government of the Kingdom of Belgium and the International Organization for Migration with support from the World Bank, the European Commission and a great number of governments worldwide. A conference steering and advisory committee was set-up prior to the event, composed of representatives of the Belgian Ministries for Foreign Affairs, Development Cooperation and Interior, IOM, as well as the World Bank, the European Commission Directorate General for Development and the European Commission Directorate General for Justice, Liberty and Security. The steering and advisory committee was in charge of the main policy and organizational aspects for the preparation of the conference and