Interpretation of Mission 66 Resources in the National

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Park Service Mission 66 Era Resources B

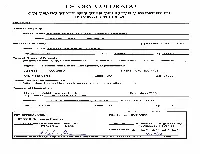

NPS Form 10-900-b (Rev. 01/2009) 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form Is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructil'.r!§ ~ ~ tloDpl lj~~r Bulletin How to Complete the Mulliple Property Doc11mentatlon Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the req lBtEa\oJcttti~ll/~ a@i~8CPace, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items X New Submission Amended Submission AUG 1 4 2015 ---- ----- Nat Register of Historie Places A. Name of Multiple Property Listing NatioAal Park Service National Park Service Mission 66 Era Resources B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Pre-Mission 66 era, 1945-1955; Mission 66 program, 1956-1966; Parkscape USA program, 1967-1972, National Park Service, nation-wide C. Form Prepared by name/title Ethan Carr (Historical Landscape Architect); Elaine Jackson-Retondo, Ph.D., (Historian, Architectural); Len Warner (Historian). The Collaborative Inc.'s 2012-2013 team comprised Rodd L. Wheaton (Architectural Historian and Supportive Research), Editor and Contributing Author; John D. Feinberg, Editor and Contributing Author; and Carly M. Piccarello, Editor. organization the Collaborative, inc. date March 2015 street & number ---------------------2080 Pearl Street telephone 303-442-3601 city or town _B_o_ul_d_er___________ __________st_a_te __ C_O _____ zi~p_c_o_d_e_8_0_30_2 __ _ e-mail [email protected] organization National Park Service Intermountain Regional Office date August 2015 street & number 1100 Old Santa Fe Trail telephone 505-988-6847 city or town Santa Fe state NM zip code 87505 e-mail sam [email protected] D. -

Overview History of the National Park Service, 2019

Description of document: Overview History of the National Park Service, 2019 Requested date: 04-June-2020 Release date: 24-June-2020 Posted date: 13-July-2020 Source of document: NPS FOIA Officer 12795 W. Alameda Parkway P.O. Box 25287 Denver, CO 80225 Fax: Call for options - 1-855-NPS-FOIA Email: [email protected] FOIA.gov The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site, and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. From: FOIA, NPS <[email protected]> Sent: Wed, Jun 24, 2020 8:30 am Subject: 20-927 NPS history presentation FOIA Response Your request is granted in full. -

Far View Visitor Center State Register Nomination, 5MT.22338 (PDF)

COLORADO STATE REGISTER OF HISTORIC PROPERTIES Property Name Far View Visitor Center, Mesa Verde National Park SECTION II Local Historic Designation Has the property received local historic designation? [ x ] no [ ] yes --- [ ]individually designated [ ] designated as part of a historic district Date designated Designated by (Name of municipality or county) Use of Property Historic Visitor Center Current vacant Original Owner National Park Service Source of Information National Park Service, Western Office of Design and Construction Year of Construction ca. 1965-1967 Source of Information National Park Service, Western Office of Design and Construction Architect, Builder, Engineer, Artist or Designer Joseph and Louise Marlow with interior work by Alder Rosenthal Architects and oversight provided by the National Park Service Western Office of Design; H.R. McBride, contractor Source of Information National Park Service (Technical Information Center); Mesa Verde National Park Archives Locational Status [ x ] Original location of structure(s) [ ] Structure(s) moved to current location Date of move SECTION III Description and Alterations (describe the current and original appearance of the property and any alterations on one or more continuation sheets) COLORADO STATE REGISTER OF HISTORIC PROPERTIES Property Name Far View Visitor Center, Mesa Verde National Park SECTION IV Significance of Property Nomination Criteria [ x ] A - property is associated with events that have made a significant contribution to history [ ] B - property is connected -

United Fund Building, 1709 Benjamin Franklin Parkway

NOMINATION OF HISTORIC BUILDING, STRUCTURE, SITE, OR OBJECT PHILADELPHIA REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES PHILADELPHIA HISTORICAL COMMISSION SUBMIT ALL ATTACHED MATERIALS ON PAPER AND IN ELECTRONIC FORM ON CD (MS WORD FORMAT) 1. ADDRESS OF HISTORIC RESOURCE (must comply with a Board of Revision of Taxes address) Street address: 1709 Benjamin Franklin Parkway Postal code: 19103-1205 Councilmanic District: 5th District 2. NAME OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Historic Name: United Fund Building Common Name: United Way Building 3. TYPE OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Building Structure Site Object 4. PROPERTY INFORMATION Condition: excellent good fair poor ruins Occupancy: occupied vacant under construction unknown Current use: Office Building 5. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION SEE ATTACHED 6. DESCRIPTION SEE ATTECHED 7. SIGNIFICANCE Period of Significance (from year to year): 1969-1971 Date(s) of construction and/or alteration: 1969-1971; concrete painted c.1995 Architect, engineer, and/or designer: Mitchell/Giurgola Associates Builder, contractor, and/or artisan: Hughes-Foulkrod Construction Co. Original owner: United Fund Other significant persons: CRITERIA FOR DESIGNATION: The historic resource satisfies the following criteria for designation (check all that apply): (a) Has significant character, interest or value as part of the development, heritage or cultural characteristics of the City, Commonwealth or Nation or is associated with the life of a person significant in the past; or, (b) Is associated with an event of importance to the history of the City, Commonwealth or -

Currents and Undercurrents: an Administrative History of Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 476 001 SO 034 781 AUTHOR McKay, Kathryn L.; Renk, Nancy F. TITLE Currents and Undercurrents: An Administrative History of Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area. INSTITUTION National Park Service (Dept. of Interior), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2002-01-00 NOTE 589p. AVAILABLE FROM Lake Roosevelt Recreation Area, 1008 Crest Drive, Coulee Dam, WA 99116. Tel: 509-633-9441; Fax: 509-633-9332; Web site: http://www.nps.gov/ laro/adhi/adhi.htm. PUB TYPE Books (010) Historical Materials (060) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF03/PC24 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS --- *Government Role; Higher Education; *Land Use; *Parks; Physical Geography; *Recreational Facilities; Rivers; Social Studies; United States History IDENTIFIERS Cultural Resources; Management Practices; National Park Service; Reservoirs ABSTRACT The 1,259-mile Columbia River flows out of Canada andacross eastern Washington state, forming the border between Washington andOregon. In 1941 the federal government dammed the Columbia River at the north endof Grand Coulee, creating a man-made reservoir named Lake Roosevelt that inundated homes, farms, and businesses, and disrupted the lives ofmany. Although Congress never enacted specific authorization to createa park, it passed generic legislation that gave the Park Service authorityat the National Recreation Area (NRA). Lake Roosevelt's shoreline totalsmore than 500 miles of cliffs and gentle slopes. The Lake Roosevelt NationalRecreation Area (LARO) was officially created in 1946. This historical study documents -

Mitchell/Giurgola's Liberty Bell Pavilion

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2001 Creation and Destruction: Mitchell/Giurgola's Liberty Bell Pavilion Bradley David Roeder University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Roeder, Bradley David, "Creation and Destruction: Mitchell/Giurgola's Liberty Bell Pavilion" (2001). Theses (Historic Preservation). 322. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/322 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Roeder, Bradley David (2002). Creation and Destruction: Mitchell/Giurgola's Liberty Bell Pavilion. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/322 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Creation and Destruction: Mitchell/Giurgola's Liberty Bell Pavilion Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Roeder, Bradley David (2002). Creation and Destruction: Mitchell/Giurgola's Liberty Bell Pavilion. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/322 uNivERsmy PENNSYLVANIA. UBKARIES CREATION AND DESTRUCTION: MITCHELL/GIURGOLA'S LIBERTY BELL PAVILION Bradley David Roeder A THESIS In Historic Preservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE 2002 Advisor Reader David G. DeLong Samuel Y. Harris Professor of Architecture Adjunct Professor of Architecture I^UOAjA/t? Graduate Group Chair i Erank G. -

Preserving the Work of Mitchell/Giurgola Associates

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1-1-2006 Preserving the Work of Mitchell/Giurgola Associates Brendan R. Beier University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Beier, Brendan R., "Preserving the Work of Mitchell/Giurgola Associates" (2006). Theses (Historic Preservation). 3. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/3 Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of Science in Historic Preservation 2006. Advisor: David G. De Long This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/3 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Preserving the Work of Mitchell/Giurgola Associates Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of Science in Historic Preservation 2006. Advisor: David G. De Long This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/3 PRESERVING THE WORK OF MITCHELL/GIURGOLA ASSOCIATES Brendan Reid Beier A THESIS in Historic Preservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN HISTORIC PRESERVATION 2006 __________________________ -

2000 Vol.22 No2

JFJLAJNINfJIN G HTI§ TO JR ~y BULLETIN OF THE INTERNATIONAL PLANNING HISTORY SOCIETY VOL. 22 NO. 2 * 2000 ISSN 0959-5805 JFI~AJNNJI)NjG IHITI§1r0~Y BULLETIN OF THE INTERNATIONAL PLANNING HISTORY SOCIETY BULLETIN OF THE INT ERNATIONAL PLANNING HISTORY SOCIETY EDITOR Dr Kiki Kafkoula Department of Urban and Regional Planning Dr Mark Clapson School of Architecture Dept. of History Aristotle University ofThessalonika University of Luton Thessalonika 54006 75 Castle Street Greece Luton Tel: 303 1 995495 I Fax: 3031 995576 LU I 3AJ UK Dr. Peter Larkham Birmingham School of Planning page 2 Tel: 01582 489034 I Fax: 01582 489014 University of Central England EDITORIAL E-mail: [email protected] Perry Barr Birmingham NOTICES 4 B42 2SU EDITORIAL BOARD UK Tcl: 0121 331 5145 ARTICLES Or Arturo Almandoz Email: [email protected] Departamento de Planificacion Urbana Political symbolism in the Canberra Landscape Universidad Simon Bolivar Professor John Muller 8 Aptdo. 89000 Department ofTown and Regional Planning Peter R. Proudfoot Caracas I086 University of Witwatersrand Venezuela Johannesburg Transatlantic dialogue: Raymond Unwin and the American planning scene Tel: (58 2) 906 4037 I 38 PO Wits2050 Mervyn Miller 17 E-mail: [email protected] South Africa Tel:Oll 7162654 / Fax: 011 403 2519 Or Halina Dunin-Woyseth E-mail: 041 [email protected] .ac.za P RACTICE Oslo School of Architecture Department of Urban Planning Professor Georgio Piccinato The Tony Garnier Urban Museum, Lyon PO Box 271 300 I Drammen Facolta di Architettura 29 Norway Universita -

An Endangered American Building

An Endangered American Building Drawing courtesy Jason Hart, CUBE design + research, LLC, Boston, MA. The National Park Service plans to remove the historically significant Cyclorama Building at Gettysburg, designed by world-renowned architect Richard Neutra. Preservationists are working world-wide to save the structure. • The Cyclorama Center at Gettysburg National Military Park was designed by the firm of Neutra & Alexander as part of the Park Service’s landmark Mission 66 program, a billion- dollar postwar government initiative aimed at improving America's national parks with the construction of new facilities. • As part of Mission 66, five parks were selected to host flagship projects designed by prominent private architects: o Wright Brothers National Monument, NC o Dinosaur National Monument, UT o Rocky Mountain National Park, CO o Petrified Forest National Park, AZ o Gettysburg National Military Park, PA • The building is among the finest public examples of modern architecture nationwide, retains high integrity, and is eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. It is a rare example of architect Richard Neutra’s institutional designs and is significant within the range of federal buildings commissioned during America’s prosperous mid- twentieth century boom years. • Citing a desire for new facilities, the Park Service recently opened a new visitor’s center at Gettysburg. The Park Service has stopped maintaining the Cyclorama Center, and plans to remove the building. • U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, Report and Recommendation in Civil Action, Recent Past Preservation Network, et al., Plaintiffs, v. John Latschar, et al., Defendants (abridged, dated 2009), found that “Defendants failed to meet the procedural obligations required of federal agencies under NEPA. -

VISITING a New Family of Visitor Centers

A_CG Fall 05Fn_cc 9/20/05 11:50 AM Page 29 BOUCHER/NPS E. JACK PHOTOS ALL VISITING kinPHOTOGRAPHS BY JACK E. BOUCHER A new family of visitor centers grew up in the national parks of the 1950s and ’60s. This recently discovered cache of images gives a glimpse of the brood fresh out of the box. Left: Its form inspired by Eero Saarinen’s Kresge Chapel at MIT, Georgia’s Fort Pulaski Visitor Center offered exhibits viewed as one reads a book—left to right—with traffic flowing smoothly clockwise. COMMON GROUND FALL 2005 29 A_CG Fall 05Fn_cc 9/20/05 11:52 AM Page 30 Lens legend Jack Boucher made a find in his basement not long ago, taking him back to his days as a young pup with the National Park Service. “I was poking around and up pops a trip to days gone by,” says Boucher. Now, owing to a box of faded color negatives— since digitally restored—you can go there, too. 30 COMMON GROUND FALL 2005 A_CG Fall 05Fn_cc 9/20/05 12:09 PM Page 31 Left, above: Hopewell Village Visitor Center, Pennsylvania. The new centers were born as the emerging interstates looked to deliver 80 million visitors by 1966, the 50th anniversary of the National Park Service. Dubbed “the city hall of the park,” the building type borrowed from its sibling, the shopping center, a place for people to park and sample a menu of attractions. Visitation had already jumped from 3 to almost 30 million between 1931 and 1948, with the floor of Yosemite Valley a parking lot littered with cars, tents, and refuse. -

Re-Inventing the National Park Visitor Center

Re-inventing the National Park Visitor Center A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture in the School of Architecture & Interior Design at the College of Design Architecture Art & Planning by Kyle Burns Spring 2011 Bachelor of Science in Architecture Committee Chair - Jeff Tilman Ph. D Abstract National parks and monuments are incredibly important elements of American culture. Preserved in their natural state, they must also be accessible for the enjoyment of society. Unfortunately accessibility usually implies built form, infrastructure, landscape alterations, and other human changes that considerably change the natural terrain of many parks. Although these human changes are essential for the traditional visitor experience, it is necessary for intelligent design, especially architecture, to integrate into the landscapes and natural elements of the park. Through personal submersion into multiple national parks across the country, visitor center analysis, and research about modernism’s effects on the park system, it has become apparent that casual design solutions are not enough to effectively allow nature to overtake people’s imprint. Parks that have begun to think about new design processes and ideas include Grand Teton and Yellowstone in Wyoming and Denali in Alaska. Thinking in a direction other than “National Park Rustic” has brought about new forms and unfamiliar volumes, creating a different kind of park experience. The parks have built significant structures on reused sites where former, ineffective buildings once stood and have introduced sustainable strategies to minimize ecological footprints. Considering the history and development of national park architecture, it is interesting to contemplate the individuality of each structure in regards to the character of a particular park. -

How Mission 66 Shaped the Visitor Experience at National Parks

~ National Trustfar ,~~ Historic Preservation® February 8, 2017 How Mission 66 Shaped the Visitor Experience at National Parks By: Lauren Walser 1 of7 The Flamingo Visitors Center at Everglades National Park. Visitation to national parks skyrocketed in the years following World War II. And with the onslaught of visitors came the need for better visitor services. So the National Park Service [Link: https://www.nps.gov/index.htm] devised an ambitious l 0-year plan to repair and modernize park infrastructure. They called the plan "Mission 66 [Link: http://www.mission66.com/] ."The efforts began in 1955 and were set to end in 1966-the National Park Service's 50th anniversary. Through this federally sponsored program, more than $1 billion was spent to rehabilitate hundreds of existing buildings; to build thousands of miles of new roads; to build hundreds of new restroom facilities, campgrounds, and picnic areas; and, perhaps most noticeably, to build more than l 00 new visitor centers. Many of those visitor centers still stand today, as emblems to the Park Service's signature Park Service Modern style. In the Winter 2017 issue [Link: /preservation-magazine/issues/winter-2017] of Preservation [Link: /preservation-magazine] magazine, we profiled one of these Mission 66 projects-the Painted Desert Community Complex [Link: /stories I pa inted-desert-commu nity-complex-retu rns-to-modern ist-roots] at Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona, a sprawling, 22-acre compound designed by Richard Neutra in the 1960s, complete with places for visitors to shop, eat, and learn about the park, as well as meeting spaces, staff housing, a maintenance facility, and a school for the children of park employees.