JAN 0 3 2001 Sites Structures by the Secrntaly of the Interior Objects 1 Total

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Park Service Mission 66 Era Resources B

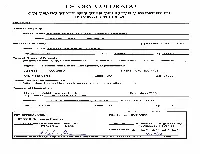

NPS Form 10-900-b (Rev. 01/2009) 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form Is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructil'.r!§ ~ ~ tloDpl lj~~r Bulletin How to Complete the Mulliple Property Doc11mentatlon Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the req lBtEa\oJcttti~ll/~ a@i~8CPace, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items X New Submission Amended Submission AUG 1 4 2015 ---- ----- Nat Register of Historie Places A. Name of Multiple Property Listing NatioAal Park Service National Park Service Mission 66 Era Resources B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Pre-Mission 66 era, 1945-1955; Mission 66 program, 1956-1966; Parkscape USA program, 1967-1972, National Park Service, nation-wide C. Form Prepared by name/title Ethan Carr (Historical Landscape Architect); Elaine Jackson-Retondo, Ph.D., (Historian, Architectural); Len Warner (Historian). The Collaborative Inc.'s 2012-2013 team comprised Rodd L. Wheaton (Architectural Historian and Supportive Research), Editor and Contributing Author; John D. Feinberg, Editor and Contributing Author; and Carly M. Piccarello, Editor. organization the Collaborative, inc. date March 2015 street & number ---------------------2080 Pearl Street telephone 303-442-3601 city or town _B_o_ul_d_er___________ __________st_a_te __ C_O _____ zi~p_c_o_d_e_8_0_30_2 __ _ e-mail [email protected] organization National Park Service Intermountain Regional Office date August 2015 street & number 1100 Old Santa Fe Trail telephone 505-988-6847 city or town Santa Fe state NM zip code 87505 e-mail sam [email protected] D. -

Overview History of the National Park Service, 2019

Description of document: Overview History of the National Park Service, 2019 Requested date: 04-June-2020 Release date: 24-June-2020 Posted date: 13-July-2020 Source of document: NPS FOIA Officer 12795 W. Alameda Parkway P.O. Box 25287 Denver, CO 80225 Fax: Call for options - 1-855-NPS-FOIA Email: [email protected] FOIA.gov The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site, and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. From: FOIA, NPS <[email protected]> Sent: Wed, Jun 24, 2020 8:30 am Subject: 20-927 NPS history presentation FOIA Response Your request is granted in full. -

Far View Visitor Center State Register Nomination, 5MT.22338 (PDF)

COLORADO STATE REGISTER OF HISTORIC PROPERTIES Property Name Far View Visitor Center, Mesa Verde National Park SECTION II Local Historic Designation Has the property received local historic designation? [ x ] no [ ] yes --- [ ]individually designated [ ] designated as part of a historic district Date designated Designated by (Name of municipality or county) Use of Property Historic Visitor Center Current vacant Original Owner National Park Service Source of Information National Park Service, Western Office of Design and Construction Year of Construction ca. 1965-1967 Source of Information National Park Service, Western Office of Design and Construction Architect, Builder, Engineer, Artist or Designer Joseph and Louise Marlow with interior work by Alder Rosenthal Architects and oversight provided by the National Park Service Western Office of Design; H.R. McBride, contractor Source of Information National Park Service (Technical Information Center); Mesa Verde National Park Archives Locational Status [ x ] Original location of structure(s) [ ] Structure(s) moved to current location Date of move SECTION III Description and Alterations (describe the current and original appearance of the property and any alterations on one or more continuation sheets) COLORADO STATE REGISTER OF HISTORIC PROPERTIES Property Name Far View Visitor Center, Mesa Verde National Park SECTION IV Significance of Property Nomination Criteria [ x ] A - property is associated with events that have made a significant contribution to history [ ] B - property is connected -

Currents and Undercurrents: an Administrative History of Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 476 001 SO 034 781 AUTHOR McKay, Kathryn L.; Renk, Nancy F. TITLE Currents and Undercurrents: An Administrative History of Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area. INSTITUTION National Park Service (Dept. of Interior), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2002-01-00 NOTE 589p. AVAILABLE FROM Lake Roosevelt Recreation Area, 1008 Crest Drive, Coulee Dam, WA 99116. Tel: 509-633-9441; Fax: 509-633-9332; Web site: http://www.nps.gov/ laro/adhi/adhi.htm. PUB TYPE Books (010) Historical Materials (060) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF03/PC24 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS --- *Government Role; Higher Education; *Land Use; *Parks; Physical Geography; *Recreational Facilities; Rivers; Social Studies; United States History IDENTIFIERS Cultural Resources; Management Practices; National Park Service; Reservoirs ABSTRACT The 1,259-mile Columbia River flows out of Canada andacross eastern Washington state, forming the border between Washington andOregon. In 1941 the federal government dammed the Columbia River at the north endof Grand Coulee, creating a man-made reservoir named Lake Roosevelt that inundated homes, farms, and businesses, and disrupted the lives ofmany. Although Congress never enacted specific authorization to createa park, it passed generic legislation that gave the Park Service authorityat the National Recreation Area (NRA). Lake Roosevelt's shoreline totalsmore than 500 miles of cliffs and gentle slopes. The Lake Roosevelt NationalRecreation Area (LARO) was officially created in 1946. This historical study documents -

Mitchell/Giurgola's Liberty Bell Pavilion

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2001 Creation and Destruction: Mitchell/Giurgola's Liberty Bell Pavilion Bradley David Roeder University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Roeder, Bradley David, "Creation and Destruction: Mitchell/Giurgola's Liberty Bell Pavilion" (2001). Theses (Historic Preservation). 322. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/322 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Roeder, Bradley David (2002). Creation and Destruction: Mitchell/Giurgola's Liberty Bell Pavilion. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/322 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Creation and Destruction: Mitchell/Giurgola's Liberty Bell Pavilion Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Roeder, Bradley David (2002). Creation and Destruction: Mitchell/Giurgola's Liberty Bell Pavilion. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/322 uNivERsmy PENNSYLVANIA. UBKARIES CREATION AND DESTRUCTION: MITCHELL/GIURGOLA'S LIBERTY BELL PAVILION Bradley David Roeder A THESIS In Historic Preservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE 2002 Advisor Reader David G. DeLong Samuel Y. Harris Professor of Architecture Adjunct Professor of Architecture I^UOAjA/t? Graduate Group Chair i Erank G. -

An Endangered American Building

An Endangered American Building Drawing courtesy Jason Hart, CUBE design + research, LLC, Boston, MA. The National Park Service plans to remove the historically significant Cyclorama Building at Gettysburg, designed by world-renowned architect Richard Neutra. Preservationists are working world-wide to save the structure. • The Cyclorama Center at Gettysburg National Military Park was designed by the firm of Neutra & Alexander as part of the Park Service’s landmark Mission 66 program, a billion- dollar postwar government initiative aimed at improving America's national parks with the construction of new facilities. • As part of Mission 66, five parks were selected to host flagship projects designed by prominent private architects: o Wright Brothers National Monument, NC o Dinosaur National Monument, UT o Rocky Mountain National Park, CO o Petrified Forest National Park, AZ o Gettysburg National Military Park, PA • The building is among the finest public examples of modern architecture nationwide, retains high integrity, and is eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. It is a rare example of architect Richard Neutra’s institutional designs and is significant within the range of federal buildings commissioned during America’s prosperous mid- twentieth century boom years. • Citing a desire for new facilities, the Park Service recently opened a new visitor’s center at Gettysburg. The Park Service has stopped maintaining the Cyclorama Center, and plans to remove the building. • U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, Report and Recommendation in Civil Action, Recent Past Preservation Network, et al., Plaintiffs, v. John Latschar, et al., Defendants (abridged, dated 2009), found that “Defendants failed to meet the procedural obligations required of federal agencies under NEPA. -

VISITING a New Family of Visitor Centers

A_CG Fall 05Fn_cc 9/20/05 11:50 AM Page 29 BOUCHER/NPS E. JACK PHOTOS ALL VISITING kinPHOTOGRAPHS BY JACK E. BOUCHER A new family of visitor centers grew up in the national parks of the 1950s and ’60s. This recently discovered cache of images gives a glimpse of the brood fresh out of the box. Left: Its form inspired by Eero Saarinen’s Kresge Chapel at MIT, Georgia’s Fort Pulaski Visitor Center offered exhibits viewed as one reads a book—left to right—with traffic flowing smoothly clockwise. COMMON GROUND FALL 2005 29 A_CG Fall 05Fn_cc 9/20/05 11:52 AM Page 30 Lens legend Jack Boucher made a find in his basement not long ago, taking him back to his days as a young pup with the National Park Service. “I was poking around and up pops a trip to days gone by,” says Boucher. Now, owing to a box of faded color negatives— since digitally restored—you can go there, too. 30 COMMON GROUND FALL 2005 A_CG Fall 05Fn_cc 9/20/05 12:09 PM Page 31 Left, above: Hopewell Village Visitor Center, Pennsylvania. The new centers were born as the emerging interstates looked to deliver 80 million visitors by 1966, the 50th anniversary of the National Park Service. Dubbed “the city hall of the park,” the building type borrowed from its sibling, the shopping center, a place for people to park and sample a menu of attractions. Visitation had already jumped from 3 to almost 30 million between 1931 and 1948, with the floor of Yosemite Valley a parking lot littered with cars, tents, and refuse. -

Re-Inventing the National Park Visitor Center

Re-inventing the National Park Visitor Center A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture in the School of Architecture & Interior Design at the College of Design Architecture Art & Planning by Kyle Burns Spring 2011 Bachelor of Science in Architecture Committee Chair - Jeff Tilman Ph. D Abstract National parks and monuments are incredibly important elements of American culture. Preserved in their natural state, they must also be accessible for the enjoyment of society. Unfortunately accessibility usually implies built form, infrastructure, landscape alterations, and other human changes that considerably change the natural terrain of many parks. Although these human changes are essential for the traditional visitor experience, it is necessary for intelligent design, especially architecture, to integrate into the landscapes and natural elements of the park. Through personal submersion into multiple national parks across the country, visitor center analysis, and research about modernism’s effects on the park system, it has become apparent that casual design solutions are not enough to effectively allow nature to overtake people’s imprint. Parks that have begun to think about new design processes and ideas include Grand Teton and Yellowstone in Wyoming and Denali in Alaska. Thinking in a direction other than “National Park Rustic” has brought about new forms and unfamiliar volumes, creating a different kind of park experience. The parks have built significant structures on reused sites where former, ineffective buildings once stood and have introduced sustainable strategies to minimize ecological footprints. Considering the history and development of national park architecture, it is interesting to contemplate the individuality of each structure in regards to the character of a particular park. -

How Mission 66 Shaped the Visitor Experience at National Parks

~ National Trustfar ,~~ Historic Preservation® February 8, 2017 How Mission 66 Shaped the Visitor Experience at National Parks By: Lauren Walser 1 of7 The Flamingo Visitors Center at Everglades National Park. Visitation to national parks skyrocketed in the years following World War II. And with the onslaught of visitors came the need for better visitor services. So the National Park Service [Link: https://www.nps.gov/index.htm] devised an ambitious l 0-year plan to repair and modernize park infrastructure. They called the plan "Mission 66 [Link: http://www.mission66.com/] ."The efforts began in 1955 and were set to end in 1966-the National Park Service's 50th anniversary. Through this federally sponsored program, more than $1 billion was spent to rehabilitate hundreds of existing buildings; to build thousands of miles of new roads; to build hundreds of new restroom facilities, campgrounds, and picnic areas; and, perhaps most noticeably, to build more than l 00 new visitor centers. Many of those visitor centers still stand today, as emblems to the Park Service's signature Park Service Modern style. In the Winter 2017 issue [Link: /preservation-magazine/issues/winter-2017] of Preservation [Link: /preservation-magazine] magazine, we profiled one of these Mission 66 projects-the Painted Desert Community Complex [Link: /stories I pa inted-desert-commu nity-complex-retu rns-to-modern ist-roots] at Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona, a sprawling, 22-acre compound designed by Richard Neutra in the 1960s, complete with places for visitors to shop, eat, and learn about the park, as well as meeting spaces, staff housing, a maintenance facility, and a school for the children of park employees. -

THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE DIVISION of INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS: the CASE for INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES, 1916-2016 a Thesis Submitt

THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE DIVISION OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS: THE CASE FOR INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES, 1916-2016 A Thesis Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS by Joana Arruda May 2016 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Seth C. Bruggeman Advisory Chair, History Dr. Hilary Iris Lowe, History Dr. John Sprinkle, Bureau Historian, National Park Service ABSTRACT In 1916 the United States National Park Service (NPS) was founded to conserve the nation’s natural and cultural landscapes as well as “to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.” While much historical analysis has been done by historians and the NPS on the agency’s national history, these scholars have ignored how the NPS was shaped by and contributed to an international history of national parks. Thus, this thesis addresses this historiographical gap and institutional forgetfulness by examining the agency’s Division of International Affairs (DIA). The DIA was established in 1961 by the NPS to foster international cooperation by building national parks overseas, which often advanced foreign policy containment initiatives in the developing world during the Cold War. Following the end of the Cold War, a significant decline in activity and staffing made it more difficult for the DIA to return to the pull of its influence just a decade or two earlier. In 1987 the DIA was renamed the Office of International Affairs (OIA) and has since suffered from many of its parent agency’s larger issues including a decline in staffing, funding, and a host of other issues that have compromised the NPS’s ability to meet its mission. -

Chapter 8 CUL TURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT GUIDELINE Page

PART 2. TREATMENT AND USE Ultimate Treatment and Use The ultimate treatment and use of this structure, as defined in the National Park Service “Project Agreement” dated December, 2002, calls for stabilization and rehabilitation of the National Historic Landmark, Quarry Visitor Center at Dinosaur National Monument. Historically, President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed Dinosaur a National Monument in 1915. Earl Douglas discovered the deposit of dinosaur bones in 1909, and later envisioned a visitor center concept prefacing the structure as it exists today. The National Park Service Mission 66 program inception and funding resulted in a park service effort to find a suitable contract architect, Anshen and Allen, Architects, for a visitor center commission resulting in Quarry Visitor Center, Dinosaur National Monument. The ultimate treatment and use of this structure, as defined in the National Park Service “Project Management Information System (PMIS 21511), is found in the document title “Stabilize and Rehabilitate Historic Quarry Visitor Center”. The PMIS further states that the building will “provide for long term protection of fossils from the elements” and “maintain a work environment that informs the public of all park resources, including a visitor contact station and cooperating association sales outlet”. “Park goals, guiding documents and the building’s listing on the National Historic Landmark mandate the protection and accessibility of the Quarry Visitor Center to park visitors.” “Quarry building would continue as the focal point of visitors coming to the monument.” The ultimate historic and current use of this structure, as defined in the “National Historic Landmark Nomination”, is “Government Recreation and Culture (Government Museum and Office)”. -

Chapter 7: Developing the Park

Chapter 7: Developing the Park Many ideas for the development of the park floated around long before the park was established and the NPS began a formal planning process. In the 1930s and 1940s, some Florida proponents of the park foresaw resort hotels, parkway roads, and even golf courses as part of the program. In 1933, Marjory Stoneman Douglas confidently wrote that: “Hotels maintained by the park service will be situated on the loveliest of the outer beaches, along the Keys, or at Cape Sable.” Five years later, G. Orren Palmer, head of the ENPC, pointed to resort-type development to convince Florida citizens of the economic benefits of a park. In a radio talk, he referred to “roads, bridges, canals, five large hotels, tourist camps, fishing camps,” and more that would sprout up not long after a park was established. Development of recreational facilities within the park had long been a goal of many of the Florida businessmen who saw the park mainly as a source of tourist dollars. It was in large part this sort of boosterism, along with the proposal for a shoreline scenic highway persistently touted by the ENPA, that had motivated leadiFng conservationists to press for a wilderness guarantee in the park’s 1934 enabling act. As discussed below in chapter 10, wilderness in the 1930s was a nebulous concept, and the NPS had developed no policies for managing wilderness. In fact, the NPS published a map shortly after 1934 showing the a scenic road travers- ing the entire shoreline of the park—the same road that Ernest Coe and the ENPA had long supported (figure 7-1, NPS recreational map of Florida).