Solving Special Operational Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Free Land Attracted Many Colonists to Texas in 1840S 3-29-92 “No Quitting Sense” We Claim Is Typically Texas

“Between the Creeks” Gwen Pettit This is a compilation of weekly newspaper columns on local history written by Gwen Pettit during 1986-1992 for the Allen Leader and the Allen American in Allen, Texas. Most of these articles were initially written and published, then run again later with changes and additions made. I compiled these articles from the Allen American on microfilm at the Allen Public Library and from the Allen Leader newspapers provided by Mike Williams. Then, I typed them into the computer and indexed them in 2006-07. Lois Curtis and then Rick Mann, Managing Editor of the Allen American gave permission for them to be reprinted on April 30, 2007, [email protected]. Please, contact me to obtain a free copy on a CD. I have given a copy of this to the Allen Public Library, the Harrington Library in Plano, the McKinney Library, the Allen Independent School District and the Lovejoy School District. Tom Keener of the Allen Heritage Guild has better copies of all these photographs and is currently working on an Allen history book. Keener offices at the Allen Public Library. Gwen was a longtime Allen resident with an avid interest in this area’s history. Some of her sources were: Pioneering in North Texas by Capt. Roy and Helen Hall, The History of Collin County by Stambaugh & Stambaugh, The Brown Papers by George Pearis Brown, The Peters Colony of Texas by Seymour V. Conner, Collin County census & tax records and verbal history from local long-time residents of the county. She does not document all of her sources. -

Copyright by Judith A. Thomas 2012

Copyright by Judith A. Thomas 2012 The Thesis Committee for Judith A. Thomas Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Live Stream Micro-Media Activism in the Occupy Movement Mediatized Co-presence, Autonomy, and the Ambivalent Face APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Karin Gwinn Wilkins Joseph D. Straubhaar Live Stream Micro-Media Activism in the Occupy Movement Mediatized Co-presence, Autonomy, and the Ambivalent Face by Judith A. Thomas, BFA Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Dedication For my husband, inspiration and co-conspirator, Rob Donald. (Photo: The First Adbusters’ Poster for Occupy Wall Street, September 2011. Acknowledgements The work of Manuel Castells on autonomous networks and communication power has had a profound impact on this scholarship. The breadth of his vision and theoretical analysis is inspiring and insightful. I hope this work contributes to the continuing critical cultural discussion of the potential of citizen micro-media in all contexts but especially the international uprisings of 2010-2012. Most especially, my sincere thanks to the following University of Texas at Austin professors whose knowledge and curiosity inspired me most: Joe Straubhaar, Paul Resta, Shanti Kumar, Sandy Stone, and especially my generous, gifted and patient supervisor, Karin Gwinn Wilkins. I will miss the depth and breadth of debate we shared, and I look forward to following your challenging work in the future. v Abstract Live Stream Micro-Media Activism in the Occupy Movement Mediatized Co-presence, Autonomy, and the Ambivalent Face Judith A. -

Street Medic Handbook for Occupy Chicago

Street Medic Handbook for Occupy Chicago and the mobilization against the 2012 NATO summit March 7, 2012 CURATED & DISTRIBUTED BY YOUR COMRADES AT THE PAPER REVOLUTION COLLECTIVE www.PaperRevolution.org FOR ADDITIONAL FREE STREET MEDIC RESOURCES VISIT US AT & DISTRIBUTE THIS LINK: www.PaperRevolution.org/Street-Medic-Guide i Foreward This is the first draft of a new approach to the street medic handbook. It is very much an experiment, adapting a variety of streetmedic and non-streetmedic material for use in the new wave of protest and rebellion sweeping the United States. Some of this material was originally intended to be used in Oaxaca, Tunisia, or Egypt, and needs further adaptation to the easily available foods, herbs, and medical realities of the urban United States. Future drafts will source all material that wasn’t written by the author, but this draft is being compiled and edited in a hurry, so that got left out. Please email any suggestions or comments on this manual to [email protected] creative commons attribution | non-commercial / non-corporate | share alike international – without copyright THIS STREET MEDIC GUIDE IS LICENSED UNDER CREATIVE COMMONS THIS GUIDE MAY BE SHARED, COPIED, ADAPTED, AND DISTRIBUTED FREELY FOR NON-COMMERCIAL PURPOSES WITH ADEQUATE ATTRIBUTION PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENT / DISCLAIMER NOTICE: THIS GUIDE IS NOT A REPLACEMENT FOR FIRST AID OR STREET MEDIC TRAINING. The information we provide within our street medic guide is intended to be used as reference material for educational purposes only. This resource in no way substitutes or qualifies an individual to act as a street medic without first obtaining proper training led by a qualified instructor. -

Sanchez and Western District Court § District 0 Kristopher Sleeman, § Plaintiffs, § § V

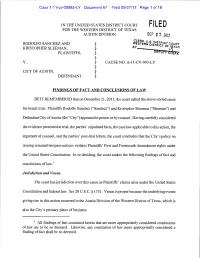

Case 1:11-cv-00993-LY Document 67 Filed 09/27/12 Page 1 of 18 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FILED FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS AUSTIN DIVISION SEP 2 7 2012 CLERK U.S. RODOLFO SANCHEZ AND WESTERN DISTRICT COURT § DISTRICT 0 KRISTOPHER SLEEMAN, § PLAINTIFFS, § § V. § CAUSE NO. A-1 1-CV-993-LY § CITY OF AUSTIN, § DEFENDANT. § FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW BE IT REMEMBERED that on December 21, 2011, the court called the above-styled cause for bench trial. Plaintiffs Rodolfo Sanchez ("Sanchez") and Kristopher Sleeman ("Sleeman") and Defendant City of Austin (the "City") appeared in person or by counsel. Having carefully considered the evidence presented at trial, the parties' stipulated facts, the case law applicable to this action, the argument of counsel, and the parties' post-trial letters, the court concludes that the City's policy on issuing criminal-trespass notices violates Plaintiffs' First and Fourteenth Amendment rights under the United States Constitution. In so deciding, the court makes the following findings of fact and conclusions of law.1 Jurisdiction and Venue The court has jurisdiction over this cause as Plaintiffs' claims arise under the United States Constitution and federal law. See 28 U.S.C. § 1331. Venue is proper because the underlying events giving rise to this action occurred in the Austin Division of the Western District of Texas, which is also the City's primary place of business. All findings of fact contained herein that are more appropriately considered conclusions of law are to be so deemed. Likewise, any conclusion of law more appropriately considered a finding of fact shall be so deemed. -

Austin Chronicle Page 1 of 3

Review: Patience - The Austin Chronicle Page 1 of 3 keyword SEARCH E-EDITION | LOG IN | REGISTER HOME NEWS FOOD MUSIC SCREENS ARTS BOOKS BLOGS CALENDAR SPECIAL PROMOTIONS ADS CLASSIFIEDS PERSONALS FOURTH OF JULY | HOT SAUCE FESTIVAL | PHOTO GALLERIES | RESTAURANT POLL | SUMMER CAMPS | CONTESTS | JOB OPENINGS FEATURED CONTENT news food music screens arts Occupy Austin Cool Off on The Grownup Lynn Shelton The Founding Occupies 7/4 – Lake Travis, Version of on the Process Fathers' First and Considers Enjoy Some Hill Fiddle Phenom Behind 'Your Declaration: Its Future Country Ruby Jane Sister's Sister' 'Let’s ’Roque!' Cuisine the arts Exhibitionism This Gilbert & Sullivan Society production has something for every connoisseur of READMORE comedy KEYWORDS FOR THIS STORY BY ADAM ROBERTS, FRI., JUNE 15, 2012 Patience, Gilbert & Sullivan Society of Austin, Ralph MacPhail Jr., Jeffrey Jones-Ragona, Meredith Ruduski, Holton Johnson, Arthur DiBianca, Janette Jones Patience Brentwood Christian School Performing Arts Center, 11908 MORE PATIENCE N. Lamar, 474-5664 Exhibitionism www.gilbertsullivan.org FRI., JUNE 18, 1999 Through June 17 Running time: 2 hr., 30 min. MORE ARTS REVIEWS Big Range Austin Dance Festival 2012, Program For some, patience is exactly what the doctor ordered when it A comes to an evening at the opera. But fear not, ye who run for the BRADF 2012's opener embraced the experimental but hills at the mere utterance of "Richard Wagner" – the Gilbert & showed deep thinking and skilled execution Sullivan Society of Austin possesses just the antidote for JONELLE SEITZ, FRI., JUNE 29, 2012 Walkürian gravitas. Theirs is a Patience of a frolicking sort, ALL ARTS REVIEWS » allegorized in the riotous operetta's title character. -

A Light at the End of the Tunnel

WE’RE THERE WHEN YOU CAN’T BE TheFRIDAY | OCTOBER 7, 2011Baylor www.baylorlariat.comLariat SPORTS Page 6 NEWS Page 4 A&E Page 5 Redemption Baylor baker makes it big Spectator sport The Bears return home from a Baylor alumna and baker Megan Rountree ‘Kingdom Hearts’ proves tough loss to play the first home whipped up some tasty treats on “The Next one-player games can still conference game of the season Great Baker” and now at her own Dallas bakery be fun for large groups Vol. 112 No. 23 © 2011, Baylor University In Print A light at the end of >> Road less traveled the tunnel Uproar artist Trannie Stevens knew from the TCU looks to fill Big 12 void beginning she wanted to join the label, but that By Krista Pirtle The Big East recently lost doesn’t mean the journey Sports Writer Pittsburgh and Syracuse to the has been easy. Atlantic Coast Conference, but TCU in place of A&M? This commissioner John Marinatto Page 5 is not a bad idea, Big 12 officials has said previously the Big East agreed unanimously. would make Pitt and Syracuse Thursday morning, the con- honor the 27-month exit agree- >> Stepping forward ference officials sent an invitation ment, meaning they couldn’t join A 5K walk in Waco aims to TCU to join the Big 12, which the ACC until 2014. to put an end to world would bring the total number of Without TCU, Pittsburgh hunger. teams in the conference to 10. and Syracuse, the remaining Big “TCU is an excellent choice as East football members would be a new member of the conference,” Louisville, West Virginia, Cincin- Page 3 Oklahoma president David Bored nati, UConn, Rutgers and South said in a statement. -

Page 1 Oct. 21

Presorted Standard U.S. Postage Paid Austin, Texas Permit No. 01949 This paper can be recycled Vol. 39 No. 23 Website: theaustinvillager.com Email: [email protected] Phone: 512-476-0082 Blog: EastAustinCommunityInfoCenter.blogspot.com October 21, 2011 National Association of Social Worers Texas Names U.S. Rep. Lloyd Doggett Links’ donation boosts funds Public Elected Official of the Year Washington— This week- for meals from Kids Cafe end at their annual conference, the National Association of So- cial Workers Texas (NASWTX) named U.S. Rep. Lloyd Doggett Public Elected Official of the Year, the highest award given to a public official on the state level, RAPPIN’ recognizing his work to advance Tommy Wyatt the cause of social justice for working Texas families through his commitment to health care, Being President public and higher education, civil and human rights, and social vs practice. Rep. Doggett recorded Congressman Lloyd Doggett Campaigning a video thanking the audience seems to be a social worker at for their support and committing heart. He has long taken on the For President Barack Obama, to continuing to work together social justice issues that social he cannot win for losing. While for their shared values. You can workers struggle with daily in the country is crying about the watch this video by clicking assisting their clients to achieve massive unemployment problem here. their potential, and enjoy as in the country, the U. S. Con- “Even though we are un- high a quality of life as possible. gress is voting against his bill der assault on so many fronts, Congressman Doggett has not to solve the problem. -

Occupy Wall Street: Examining a Current Event As It Happens Elizabeth Bellows, Michele Bauml, Sherry Field, and Mary Ledbetter

Social Studies and the Young Learner 24 (4), pp. 18–22 ©2012 National Council for the Social Studies Occupy Wall Street: Examining a Current Event as It Happens Elizabeth Bellows, Michele Bauml, Sherry Field, and Mary Ledbetter On September 17, 2011 (Constitution Day), Occupy Wall and their Constitutional rights during Celebrate Freedom Street began as a protest movement when approximately 2,000 Week. The third week of September, the social studies cur- supporters assembled in lower Manhattan’s Zuccotti Park. riculum in Texas (grades 3-12) focuses on the Declaration of The group’s concerns focused on the corporate role in the Independence and the U.S. Constitution, including the Bill of current financial crisis and economic inequality. On October Rights. For fifth graders, the state curriculum indicates students 1, a large group of protesters marched across the Brooklyn must be able to “describe the fundamental rights guaranteed by Bridge, causing traffic problems and generating a great deal each amendment in the Bill of Rights … including … the right of publicity. As the protesting continued, U.S. Representative to assemble and petition the government.”3 Because Occupy Eric Cantor (R-Va.) expressed his view during an appearance Wall Street began during Celebrate Freedom Week, the event on CBS News: “I for one am increasingly concerned about served as a powerful contemporary example that helped her the growing mobs occupying Wall Street and the other cities ten-year-old students understand the meaning of citizens’ right across the country.”1 Rhetoric both in support of and against to assemble. the protest began to flood the media. -

Spooky Business: Corporate Espionage Against Nonprofit Organizations

Spooky Business: Corporate Espionage Against Nonprofit Organizations By Gary Ruskin Essential Information P.O Box 19405 Washington, DC 20036 (202) 387-8030 November 20, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 INTRODUCTION 5 The brave new world of corporate espionage 5 The rise of corporate espionage against nonprofit organizations 6 NARRATIVES OF CORPORATE ESPIONAGE 9 Beckett Brown International vs. many nonprofit groups 9 The Center for Food Safety, Friends of the Earth and GE Food Alert 13 U.S. Public Interest Research Group, Friends of the Earth, National Environmental Trust/GE Food Alert, Center for Food Safety, Environmental Media Services, Environmental Working Group, Institute for Global Communications, Pesticide Action Network. 15 Fenton Communications 15 Greenpeace, CLEAN and the Lake Charles Project 16 North Valley Coalition 17 Nursing home activists 17 Mary Lou Sapone and the Brady Campaign 17 US Chamber of Commerce/HBGary Federal/Hunton & Williams vs. U.S. Chamber Watch/Public Citizen/Public Campaign/MoveOn.org/Velvet Revolution/Center for American Progress/Tides Foundation/Justice Through Music/Move to Amend/Ruckus Society 18 HBGary Federal/Hunton & Williams/Bank of America vs. WikiLeaks 21 Chevron/Kroll in Ecuador 22 Walmart vs. Up Against the Wal 23 Électricité de France vs. Greenpeace 23 E.ON/Scottish Resources Group/Scottish Power/Vericola/Rebecca Todd vs. the Camp for Climate Action 25 Burger King and Diplomatic Tactical Services vs. the Coalition of Immokalee Workers 26 The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers Association and others vs. James Love/Knowledge Ecology International 26 Feld Entertainment vs. PETA, PAWS and other animal protection groups 27 BAE vs. -

Street Medic Handbook Spreading Calm, Not Dying

CHICAGO ACTION MEDICAL STREET MEDIC HANDBOOK CONTAINING A LARGE COLLECTION OF HIGHLY ESTEEMED FIRST AID TIPS AND TRICKS, NAMELY: SPREADING CALM, PATIENT ASSESSMENT, NOT DYING, BUDDY ROLES SELECTED BY EXPERIENCED STREET MEDICS FOR THE USE OF PUBLICANS AND PROTESTERS IN GENERAL, ADAPTED FROM ROSEHIP MEDIC COLLECTIVE AND OTHER SOURCES EDITED BY E. MACK. PRICE ONE SHILLING CHICAGO: TYPESET BY E. MACK, ROOSEVELT ROAD. About this Handbook December 2013 This is the second edition of our handbook. In future editions we hope to expand and clarify our teaching style’s emphasis of prevention-based care. This handbook is written using the pronouns he, him, his, she, her, and hers. While we recognize that this usage excludes other genders, we chose this approach in an effort to make the handbook accessible to people whose first language is not English. You can email us at [email protected]. We look forward to hearing your suggestions, questions, and criticisms about this handbook. Typeset by Esther Mack in LATEX- Memoir ii 1 Introduction 1 Fainting . 43 What are street medics? . 1 Abdominal illnesses . 43 Why medic? . 4 Diabetes . 44 2 Before You Hit The Streets 6 8 Environmental Health 46 Prevention by self-care . 6 Dehydration . 46 Medic fashions and kits . 8 Heat . 46 Buddies . 8 Not enough heat . 47 Ethical dilemmas . 9 9 Police 49 3 Streetside Manner 11 Rumor control . 49 Principles . 11 Police tactics . 49 Legal aspects . 13 Shit! We’re gonna get arrested! . 55 EMS and Police . 15 Handcuff injuries . 59 4 Scene Survey 18 10 Herbal First Aid and Aftercare 65 Triage . -

Challenger OCT 2016 NEWSPAPER 20

The $2.00 official OR MORE SUGGESTED DONATION ChallengerChallengerstreet newspaper October 2016 Vol 6, Issue 6 A newspaper that matters (63rd issue) www.challengernewspaper.org [email protected] A Free Press 95% H OMELESS WRITERS CONTENTS ARE COPYRIGHTED , INSIDE PO Box 151574 Austin, TX 78715 512-560-4735 Voice Of The People NO USE W/O PERMISSION ART By Rana Ghana 1 Join Our Gang 1 By Trinity Staff 2 Ads/Ad rates Announcements Safe Sleep 3 A Capitol Part 8 Final 4 By Scott Hoft R Gone Home Letter to 5 Christian By Dee Slavery By Any Other Name 6 T By Marcilas Reprinted from Dec 2015 BY RANA HANA Thought Experiments 7 G By Rambo KoolAid’s Drag Update 7 Jail Mail By CNP Homeless Soulmate 7 OIN J By Emmy Town Lake Angel Literary By John Curran 8 OUR ART By Sally Guevara 8 Distributors Wanted , Lap- 9 GANG tops, Tent City PHOTO BY 10-11 Resource Directory Cntr TRINITY Pull out, Subscriber Form, Challenger Code STAFF Critical Thinking 12 By The Gadfly My Personal Experience 12 By Kennilou Taylor PROFESSIONAL HOMELESS QUALIFICATIONS When Your Friends Live 12 Outside By Courtney Y IRATE OE EPRINTED FROM EB EDITED B P J R F 2016 13 Let’s Get More Started By Jenn Theone Aside from being judged by the shallow, ignorant and blind, think about this a bit: who ART By Zebra 13 would be scared to hire anyone who puts homeless on a job application as a unique and Distributer Locations 14 extreme educational experience? It is more real than school, any school. -

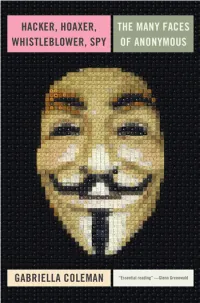

Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: the Story of Anonymous

hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy the many faces of anonymous Gabriella Coleman London • New York First published by Verso 2014 © Gabriella Coleman 2014 The partial or total reproduction of this publication, in electronic form or otherwise, is consented to for noncommercial purposes, provided that the original copyright notice and this notice are included and the publisher and the source are clearly acknowledged. Any reproduction or use of all or a portion of this publication in exchange for financial consideration of any kind is prohibited without permission in writing from the publisher. The moral rights of the author have been asserted 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201 www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-583-9 eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-584-6 (US) eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-689-8 (UK) British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the library of congress Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall Printed in the US by Maple Press Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY I dedicate this book to the legions behind Anonymous— those who have donned the mask in the past, those who still dare to take a stand today, and those who will surely rise again in the future.