Street Medic Handbook for Occupy Chicago

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Free Land Attracted Many Colonists to Texas in 1840S 3-29-92 “No Quitting Sense” We Claim Is Typically Texas

“Between the Creeks” Gwen Pettit This is a compilation of weekly newspaper columns on local history written by Gwen Pettit during 1986-1992 for the Allen Leader and the Allen American in Allen, Texas. Most of these articles were initially written and published, then run again later with changes and additions made. I compiled these articles from the Allen American on microfilm at the Allen Public Library and from the Allen Leader newspapers provided by Mike Williams. Then, I typed them into the computer and indexed them in 2006-07. Lois Curtis and then Rick Mann, Managing Editor of the Allen American gave permission for them to be reprinted on April 30, 2007, [email protected]. Please, contact me to obtain a free copy on a CD. I have given a copy of this to the Allen Public Library, the Harrington Library in Plano, the McKinney Library, the Allen Independent School District and the Lovejoy School District. Tom Keener of the Allen Heritage Guild has better copies of all these photographs and is currently working on an Allen history book. Keener offices at the Allen Public Library. Gwen was a longtime Allen resident with an avid interest in this area’s history. Some of her sources were: Pioneering in North Texas by Capt. Roy and Helen Hall, The History of Collin County by Stambaugh & Stambaugh, The Brown Papers by George Pearis Brown, The Peters Colony of Texas by Seymour V. Conner, Collin County census & tax records and verbal history from local long-time residents of the county. She does not document all of her sources. -

Copyright by Judith A. Thomas 2012

Copyright by Judith A. Thomas 2012 The Thesis Committee for Judith A. Thomas Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Live Stream Micro-Media Activism in the Occupy Movement Mediatized Co-presence, Autonomy, and the Ambivalent Face APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Karin Gwinn Wilkins Joseph D. Straubhaar Live Stream Micro-Media Activism in the Occupy Movement Mediatized Co-presence, Autonomy, and the Ambivalent Face by Judith A. Thomas, BFA Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Dedication For my husband, inspiration and co-conspirator, Rob Donald. (Photo: The First Adbusters’ Poster for Occupy Wall Street, September 2011. Acknowledgements The work of Manuel Castells on autonomous networks and communication power has had a profound impact on this scholarship. The breadth of his vision and theoretical analysis is inspiring and insightful. I hope this work contributes to the continuing critical cultural discussion of the potential of citizen micro-media in all contexts but especially the international uprisings of 2010-2012. Most especially, my sincere thanks to the following University of Texas at Austin professors whose knowledge and curiosity inspired me most: Joe Straubhaar, Paul Resta, Shanti Kumar, Sandy Stone, and especially my generous, gifted and patient supervisor, Karin Gwinn Wilkins. I will miss the depth and breadth of debate we shared, and I look forward to following your challenging work in the future. v Abstract Live Stream Micro-Media Activism in the Occupy Movement Mediatized Co-presence, Autonomy, and the Ambivalent Face Judith A. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

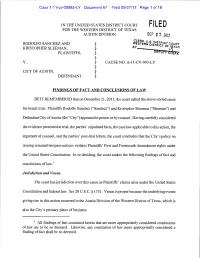

Sanchez and Western District Court § District 0 Kristopher Sleeman, § Plaintiffs, § § V

Case 1:11-cv-00993-LY Document 67 Filed 09/27/12 Page 1 of 18 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FILED FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS AUSTIN DIVISION SEP 2 7 2012 CLERK U.S. RODOLFO SANCHEZ AND WESTERN DISTRICT COURT § DISTRICT 0 KRISTOPHER SLEEMAN, § PLAINTIFFS, § § V. § CAUSE NO. A-1 1-CV-993-LY § CITY OF AUSTIN, § DEFENDANT. § FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW BE IT REMEMBERED that on December 21, 2011, the court called the above-styled cause for bench trial. Plaintiffs Rodolfo Sanchez ("Sanchez") and Kristopher Sleeman ("Sleeman") and Defendant City of Austin (the "City") appeared in person or by counsel. Having carefully considered the evidence presented at trial, the parties' stipulated facts, the case law applicable to this action, the argument of counsel, and the parties' post-trial letters, the court concludes that the City's policy on issuing criminal-trespass notices violates Plaintiffs' First and Fourteenth Amendment rights under the United States Constitution. In so deciding, the court makes the following findings of fact and conclusions of law.1 Jurisdiction and Venue The court has jurisdiction over this cause as Plaintiffs' claims arise under the United States Constitution and federal law. See 28 U.S.C. § 1331. Venue is proper because the underlying events giving rise to this action occurred in the Austin Division of the Western District of Texas, which is also the City's primary place of business. All findings of fact contained herein that are more appropriately considered conclusions of law are to be so deemed. Likewise, any conclusion of law more appropriately considered a finding of fact shall be so deemed. -

Austin Chronicle Page 1 of 3

Review: Patience - The Austin Chronicle Page 1 of 3 keyword SEARCH E-EDITION | LOG IN | REGISTER HOME NEWS FOOD MUSIC SCREENS ARTS BOOKS BLOGS CALENDAR SPECIAL PROMOTIONS ADS CLASSIFIEDS PERSONALS FOURTH OF JULY | HOT SAUCE FESTIVAL | PHOTO GALLERIES | RESTAURANT POLL | SUMMER CAMPS | CONTESTS | JOB OPENINGS FEATURED CONTENT news food music screens arts Occupy Austin Cool Off on The Grownup Lynn Shelton The Founding Occupies 7/4 – Lake Travis, Version of on the Process Fathers' First and Considers Enjoy Some Hill Fiddle Phenom Behind 'Your Declaration: Its Future Country Ruby Jane Sister's Sister' 'Let’s ’Roque!' Cuisine the arts Exhibitionism This Gilbert & Sullivan Society production has something for every connoisseur of READMORE comedy KEYWORDS FOR THIS STORY BY ADAM ROBERTS, FRI., JUNE 15, 2012 Patience, Gilbert & Sullivan Society of Austin, Ralph MacPhail Jr., Jeffrey Jones-Ragona, Meredith Ruduski, Holton Johnson, Arthur DiBianca, Janette Jones Patience Brentwood Christian School Performing Arts Center, 11908 MORE PATIENCE N. Lamar, 474-5664 Exhibitionism www.gilbertsullivan.org FRI., JUNE 18, 1999 Through June 17 Running time: 2 hr., 30 min. MORE ARTS REVIEWS Big Range Austin Dance Festival 2012, Program For some, patience is exactly what the doctor ordered when it A comes to an evening at the opera. But fear not, ye who run for the BRADF 2012's opener embraced the experimental but hills at the mere utterance of "Richard Wagner" – the Gilbert & showed deep thinking and skilled execution Sullivan Society of Austin possesses just the antidote for JONELLE SEITZ, FRI., JUNE 29, 2012 Walkürian gravitas. Theirs is a Patience of a frolicking sort, ALL ARTS REVIEWS » allegorized in the riotous operetta's title character. -

Spartan Daily (November 8, 2011)

AACCESSCCESS MMAGAZINEAGAZINE iiss ccomingoming iinn tthishis TThursday’shursday’s issue!issue! Oaxaca's tasty treasures Tuesday SPARTAN DAILY A&E p. 3 Shoot to thrill! November 8, 2011 Volume 137, Issue 39 SpartanDaily.com Sports p. 2 Education costs prompt student jobs program by Margaret Baum through as many channels as possible, Staff Writer he said. Th e Career Center will off er a new "We need to provide another means way to help students fi nd jobs with of employment other than Sparta Jobs a trial drop-in interview program on and job fairs on campus," Newell said. Tuesday. He said because of construction Th e program, which runs tomorrow work, employers are no longer able to from 12 to 3 p.m., will off er students do informal interviews at tables. a professional, but less formal way of Th e drop-in interviews will be for connecting with employers, accord- two diff erent companies: Extreme Attendees joined members of the San Jose Spokes Expo in the Spartan Complex on Monday. The event pro- ing to Daniel Newell, job development Learning Inc. and Crowne Plaza Inn, wheelchair basketball team for a few games of half-court vided opportunities to practice rugby, volleyball, soccer and marketing specialist for the Career according to a fl ier handed out by the four-on-four basketball during the SJSU Disability Sport and goal ball. Photo by Jasper Rubenstein / Spartan Daily Center. Career Center on Monday. "Th is is just a pilot," he said. "We are Extreme Learning is looking for an trying to provide as many channels of online academic coach for their Mor- employment as possible." gan Hill location and Crowne Plaza is Adapting to adversity Newell said his position was created looking for a full-time house person, a this year to help fi nd more jobs for stu- part-time room att endant and a part- dents in a time when they need it most time bellhop. -

1 United States District Court for the District Of

Case 1:13-cv-00595-RMC Document 18 Filed 03/12/14 Page 1 of 31 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) RYAN NOAH SHAPIRO, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 13-595 (RMC) ) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, ) ) Defendant. ) ) OPINION Ryan Noah Shapiro sues the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), 5 U.S.C. § 552, and the Privacy Act (PA), 5 U.S.C. § 552a, to compel the release of records concerning “Occupy Houston,” an offshoot of the protest movement and New York City encampment known as “Occupy Wall Street.” Mr. Shapiro seeks FBI records regarding Occupy Houston generally and an alleged plot by unidentified actors to assassinate the leaders of Occupy Houston. FBI has moved to dismiss or for summary judgment.1 The Motion will be granted in part and denied in part. I. FACTS Ryan Noah Shapiro is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Science, Technology, and Society at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Compl. [Dkt. 1] ¶ 2. In early 2013, Mr. Shapiro sent three FOIA/PA requests to FBI for records concerning Occupy Houston, a group of protesters in Houston, Texas, affiliated with the Occupy Wall Street protest movement that began in New York City on September 17, 2011. Id. ¶¶ 8-13. Mr. Shapiro 1 FBI is a component of the Department of Justice (DOJ). While DOJ is the proper defendant in the instant litigation, the only records at issue here are FBI records. For ease of reference, this Opinion refers to FBI as Defendant. 1 Case 1:13-cv-00595-RMC Document 18 Filed 03/12/14 Page 2 of 31 explained that his “research and analytical expertise . -

A Light at the End of the Tunnel

WE’RE THERE WHEN YOU CAN’T BE TheFRIDAY | OCTOBER 7, 2011Baylor www.baylorlariat.comLariat SPORTS Page 6 NEWS Page 4 A&E Page 5 Redemption Baylor baker makes it big Spectator sport The Bears return home from a Baylor alumna and baker Megan Rountree ‘Kingdom Hearts’ proves tough loss to play the first home whipped up some tasty treats on “The Next one-player games can still conference game of the season Great Baker” and now at her own Dallas bakery be fun for large groups Vol. 112 No. 23 © 2011, Baylor University In Print A light at the end of >> Road less traveled the tunnel Uproar artist Trannie Stevens knew from the TCU looks to fill Big 12 void beginning she wanted to join the label, but that By Krista Pirtle The Big East recently lost doesn’t mean the journey Sports Writer Pittsburgh and Syracuse to the has been easy. Atlantic Coast Conference, but TCU in place of A&M? This commissioner John Marinatto Page 5 is not a bad idea, Big 12 officials has said previously the Big East agreed unanimously. would make Pitt and Syracuse Thursday morning, the con- honor the 27-month exit agree- >> Stepping forward ference officials sent an invitation ment, meaning they couldn’t join A 5K walk in Waco aims to TCU to join the Big 12, which the ACC until 2014. to put an end to world would bring the total number of Without TCU, Pittsburgh hunger. teams in the conference to 10. and Syracuse, the remaining Big “TCU is an excellent choice as East football members would be a new member of the conference,” Louisville, West Virginia, Cincin- Page 3 Oklahoma president David Bored nati, UConn, Rutgers and South said in a statement. -

Page 1 Oct. 21

Presorted Standard U.S. Postage Paid Austin, Texas Permit No. 01949 This paper can be recycled Vol. 39 No. 23 Website: theaustinvillager.com Email: [email protected] Phone: 512-476-0082 Blog: EastAustinCommunityInfoCenter.blogspot.com October 21, 2011 National Association of Social Worers Texas Names U.S. Rep. Lloyd Doggett Links’ donation boosts funds Public Elected Official of the Year Washington— This week- for meals from Kids Cafe end at their annual conference, the National Association of So- cial Workers Texas (NASWTX) named U.S. Rep. Lloyd Doggett Public Elected Official of the Year, the highest award given to a public official on the state level, RAPPIN’ recognizing his work to advance Tommy Wyatt the cause of social justice for working Texas families through his commitment to health care, Being President public and higher education, civil and human rights, and social vs practice. Rep. Doggett recorded Congressman Lloyd Doggett Campaigning a video thanking the audience seems to be a social worker at for their support and committing heart. He has long taken on the For President Barack Obama, to continuing to work together social justice issues that social he cannot win for losing. While for their shared values. You can workers struggle with daily in the country is crying about the watch this video by clicking assisting their clients to achieve massive unemployment problem here. their potential, and enjoy as in the country, the U. S. Con- “Even though we are un- high a quality of life as possible. gress is voting against his bill der assault on so many fronts, Congressman Doggett has not to solve the problem. -

Occupy Wall Street: Examining a Current Event As It Happens Elizabeth Bellows, Michele Bauml, Sherry Field, and Mary Ledbetter

Social Studies and the Young Learner 24 (4), pp. 18–22 ©2012 National Council for the Social Studies Occupy Wall Street: Examining a Current Event as It Happens Elizabeth Bellows, Michele Bauml, Sherry Field, and Mary Ledbetter On September 17, 2011 (Constitution Day), Occupy Wall and their Constitutional rights during Celebrate Freedom Street began as a protest movement when approximately 2,000 Week. The third week of September, the social studies cur- supporters assembled in lower Manhattan’s Zuccotti Park. riculum in Texas (grades 3-12) focuses on the Declaration of The group’s concerns focused on the corporate role in the Independence and the U.S. Constitution, including the Bill of current financial crisis and economic inequality. On October Rights. For fifth graders, the state curriculum indicates students 1, a large group of protesters marched across the Brooklyn must be able to “describe the fundamental rights guaranteed by Bridge, causing traffic problems and generating a great deal each amendment in the Bill of Rights … including … the right of publicity. As the protesting continued, U.S. Representative to assemble and petition the government.”3 Because Occupy Eric Cantor (R-Va.) expressed his view during an appearance Wall Street began during Celebrate Freedom Week, the event on CBS News: “I for one am increasingly concerned about served as a powerful contemporary example that helped her the growing mobs occupying Wall Street and the other cities ten-year-old students understand the meaning of citizens’ right across the country.”1 Rhetoric both in support of and against to assemble. the protest began to flood the media. -

DRAFT Curriculum Vitae Deana a Rohlinger

DRAFT Curriculum Vitae Deana A Rohlinger Last Revised: January 30, 2020 General Information University address: Sociology College of Social Sciences and Public Policy Bellamy Building 0526 Florida State University Tallahassee, Florida 32306-2270 E-mail address: [email protected] Web site: www.DeanaRohlinger.com Professional Preparation 2004 Doctor of Philosophy, University of California, Irvine. Major: Sociology. 2001 Master of Arts, University of California, Irvine. Major: Social Science. 1999 Master of Arts, California State University, San Bernardino. Major: Interdisciplinary Studies (Sociology and Communication Studies). 1995 Bachelor of Arts, University of Arizona. Major: Communication (Mass Communication Studies). Professional Experience 2017–present Associate Dean for Faculty Development and Community Engagement, College of Social Sciences and Public Policy, Florida State University. 2015–present Professor, Sociology, Florida State University. 2006–present Research Associate, Pepper Institute on Aging and Public Policy, Florida State University. 2010–2015 Associate Professor, Sociology, Florida State University. 2004–2010 Assistant Professor, Sociology, Florida State University. DRAFT Vita for Deana A Rohlinger Honors, Awards, and Prizes Graduate Mentoring Award, Sociology Graduate Student Union (2017). Graduate Teaching Award, Sociology Graduate Student Union, Florida State University (2016). University Graduate Teaching Award, Florida State University (2015). Honorable Mention for Excellence in Online Teaching, Office of Distance Learning, Florida State University (2013). Seminole Leadership Award, Division of Student Affairs, Florida State University (2013). Graduate Mentorship Award, Sociology Graduate Student Union, Florida State University (2010). University Teaching Award, Florida State University (2007). J. Michael "Best" Teacher Award, Florida State University (2006). Outstanding Graduate Scholarship Award, School of Social Science at the University of California-Irvine (2003). -

Chicago: a City on the Brink

Chicago: A City on the Brink Andrew J. DIAMOND Originally scheduled to host the next G8 summit, Chicago has been bypassed in favor of Camp David. No wonder: the “the city that works” works no more. With a terrible youth unemployment rate and municipal governance that has consistently denied its African American residents the services and jobs they deserve, Chicago has fostered despair like no other city its size. Spring will be hot. To behold the Chicago of today—a city mired in a draconian austerity program in the face of a nearly $700 million budget deficit, where the homicide rate more than doubles those of New York and Los Angeles, and where the school board recently voted to close ten failing schools and overhaul another seven—it is hard to imagine that people once commonly referred to it as “the city that works.” In fact, this nickname, which was first evoked in a 1971 Newsweek article lauding Mayor Richard J. Daley’s ability to create an efficient infrastructure for business and everyday urban life during a moment when other cities were floundering, conveyed a double-meaning—that Chicagoans worked hard and that their mayor made the city work efficiently for them. “[I]t is a demonstrable fact,” Newsweek reported, “that Chicago is that most wondrous of exceptions—a major American city that actually works.”1 The phrase began appearing in Chicago newspapers by 1972, and then in the Washington Post and New York Times in 1974 and 1975. Chicago defined this brand so effectively, that by the time its beloved 1 Frank Maier, “Chicago’s Daley: How to Run a City,” Newsweek, April 5, 1971.