Where Is My Tribe Queer Activism in the Occupy Movements.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Real Democracy in the Occupy Movement

NO STABLE GROUND: REAL DEMOCRACY IN THE OCCUPY MOVEMENT ANNA SZOLUCHA PhD Thesis Department of Sociology, Maynooth University November 2014 Head of Department: Prof. Mary Corcoran Supervisor: Dr Laurence Cox Rodzicom To my Parents ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis is an outcome of many joyous and creative (sometimes also puzzling) encounters that I shared with the participants of Occupy in Ireland and the San Francisco Bay Area. I am truly indebted to you for your unending generosity, ingenuity and determination; for taking the risks (for many of us, yet again) and continuing to fight and create. It is your voices and experiences that are central to me in these pages and I hope that you will find here something that touches a part of you, not in a nostalgic way, but as an impulse to act. First and foremost, I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to my supervisor, Dr Laurence Cox, whose unfaltering encouragement, assistance, advice and expert knowledge were invaluable for the successful completion of this research. He was always an enormously responsive and generous mentor and his critique helped sharpen this thesis in many ways. Thank you for being supportive also in so many other areas and for ushering me in to the complex world of activist research. I am also grateful to Eddie Yuen who helped me find my way around Oakland and introduced me to many Occupy participants – your help was priceless and I really enjoyed meeting you. I wanted to thank Prof. Szymon Wróbel for debates about philosophy and conversations about life as well as for his continuing support. -

Free Land Attracted Many Colonists to Texas in 1840S 3-29-92 “No Quitting Sense” We Claim Is Typically Texas

“Between the Creeks” Gwen Pettit This is a compilation of weekly newspaper columns on local history written by Gwen Pettit during 1986-1992 for the Allen Leader and the Allen American in Allen, Texas. Most of these articles were initially written and published, then run again later with changes and additions made. I compiled these articles from the Allen American on microfilm at the Allen Public Library and from the Allen Leader newspapers provided by Mike Williams. Then, I typed them into the computer and indexed them in 2006-07. Lois Curtis and then Rick Mann, Managing Editor of the Allen American gave permission for them to be reprinted on April 30, 2007, [email protected]. Please, contact me to obtain a free copy on a CD. I have given a copy of this to the Allen Public Library, the Harrington Library in Plano, the McKinney Library, the Allen Independent School District and the Lovejoy School District. Tom Keener of the Allen Heritage Guild has better copies of all these photographs and is currently working on an Allen history book. Keener offices at the Allen Public Library. Gwen was a longtime Allen resident with an avid interest in this area’s history. Some of her sources were: Pioneering in North Texas by Capt. Roy and Helen Hall, The History of Collin County by Stambaugh & Stambaugh, The Brown Papers by George Pearis Brown, The Peters Colony of Texas by Seymour V. Conner, Collin County census & tax records and verbal history from local long-time residents of the county. She does not document all of her sources. -

RELATIONSHIP THERAPY RELATIONSHIP THERAPY Making Arab Police Reform Work

CHAILLOT PAPER / PAPER CHAILLOT 160 RELATIONSHIP THERAPY RELATIONSHIP THERAPY RELATIONSHIP Making Arab police reform work | MAKING ARAB POLICE REFORM WORK REFORM POLICE ARAB MAKING By Florence Gaub and Alex Walsh CHAILLOT PAPER / 160 November 2020 RELATIONSHIP THERAPY Making Arab police reform work By Florence Gaub and Alex Walsh CHAILLOT PAPER / 160 November 2020 European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS) 100, avenue de Suffren 75015 Paris http://www.iss.europa.eu Director: Gustav Lindstrom © EU Institute for Security Studies, 2020. Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union. print ISBN 978-92-9198-970-6 online ISBN 978-92-9198-969-0 CATALOGUE NUMBER QN-AA-20-004-EN-C CATALOGUE NUMBER QN-AA-20-004-EN-N ISSN 1017-7566 ISSN 1683-4917 DOI 10.2815/645771 DOI 10.2815/791794 Published by the EU Institute for Security Studies and printed in Belgium by Bietlot. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2020. Cover image credit: Hussein Malla/AP/SIPA The authors Florence Gaub is the Deputy Director of the EUISS. She specialises in strategic foresight, as well as security and conflict in the Middle East and North Africa. Alex Walsh has worked on police reform and stabilisation programming in Lebanon, Jordan, Tunisia and Syria. He currently works with the International Security Sector Advisory Team (ISSAF) in Geneva. Acknowledgements This publication was informed by two events co-organised with the Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung, the first in Tunis in December 2018, and the second in Amman in March 2019 The EUISS Chaillot Paper series The Chaillot Paper series, launched in 1991, takes its name from the Chaillot hill in the Trocadéro area of Paris, where the Institute’s first premises were located in the building oc- cupied by the Western European Union (WEU). -

The Arab Spring: an Empirical Investigation

Protests and the Arab Spring: An Empirical Investigation Tansa George Massoud, Bucknell University John A. Doces, Bucknell University Christopher Magee, Bucknell University Keywords: Arab Spring, protests, events data, political grievances, diffusion Acknowledgements: We would like to thank Polity’s editor-in-chief and anonymous reviewers for their comments. We also thank Emily Brandes for her valuable assistance. All errors remain our own. 1 Abstract This article discusses a variety of major explanations for the intensity of recent protests in Arab states and investigates whether there is empirical support for them. We survey various political, economic, and social factors and develop a comprehensive empirical model to estimate the structural determinants of protests in 19 Arab League states between 1990 and 2011, measured using events data. The results show that protests were stronger in countries with higher inflation, higher levels of corruption, lower levels of freedom, and more use of the internet and cell phones. Protests were also more frequent in countries with partial democracies and factional politics. We find no evidence for the common argument that the surge in protests in 2011 was linked to a bulge in the youth population. Overall, we conclude that these economic, political, and social variables help to explain which countries had stronger protest movements, but that they cannot explain the timing of those revolts. We suggest that a contagion model can help explain the quick spread of protests across the region in 2011, and we conduct a preliminary test of that possibility. 2 I. Introduction The Arab revolts started in Tunisia in December 2010 and spread across the Middle East and North Africa with great speed in early 2011.1 In Tunisia and Egypt, loosely organized groups using mostly nonviolent techniques managed to topple regimes that had been in power for decades. -

Copyright by Judith A. Thomas 2012

Copyright by Judith A. Thomas 2012 The Thesis Committee for Judith A. Thomas Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Live Stream Micro-Media Activism in the Occupy Movement Mediatized Co-presence, Autonomy, and the Ambivalent Face APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Karin Gwinn Wilkins Joseph D. Straubhaar Live Stream Micro-Media Activism in the Occupy Movement Mediatized Co-presence, Autonomy, and the Ambivalent Face by Judith A. Thomas, BFA Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Dedication For my husband, inspiration and co-conspirator, Rob Donald. (Photo: The First Adbusters’ Poster for Occupy Wall Street, September 2011. Acknowledgements The work of Manuel Castells on autonomous networks and communication power has had a profound impact on this scholarship. The breadth of his vision and theoretical analysis is inspiring and insightful. I hope this work contributes to the continuing critical cultural discussion of the potential of citizen micro-media in all contexts but especially the international uprisings of 2010-2012. Most especially, my sincere thanks to the following University of Texas at Austin professors whose knowledge and curiosity inspired me most: Joe Straubhaar, Paul Resta, Shanti Kumar, Sandy Stone, and especially my generous, gifted and patient supervisor, Karin Gwinn Wilkins. I will miss the depth and breadth of debate we shared, and I look forward to following your challenging work in the future. v Abstract Live Stream Micro-Media Activism in the Occupy Movement Mediatized Co-presence, Autonomy, and the Ambivalent Face Judith A. -

Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances

SWP Research Paper Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber (Eds.) Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances RP 5 June 2015 Berlin All rights reserved. © Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2015 SWP Research Papers are peer reviewed by senior researchers and the execu- tive board of the Institute. They express exclusively the personal views of the authors. SWP Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Ludwigkirchplatz 34 10719 Berlin Germany Phone +49 30 880 07-0 Fax +49 30 880 07-100 www.swp-berlin.org [email protected] ISSN 1863-1053 Translation by Meredith Dale (Updated English version of SWP-Studie 7/2015) Table of Contents 5 Problems and Recommendations 7 Jihadism in Africa: An Introduction Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 13 Al-Shabaab: Youth without God Annette Weber 31 Libya: A Jihadist Growth Market Wolfram Lacher 51 Going “Glocal”: Jihadism in Algeria and Tunisia Isabelle Werenfels 69 Spreading Local Roots: AQIM and Its Offshoots in the Sahara Wolfram Lacher and Guido Steinberg 85 Boko Haram: Threat to Nigeria and Its Northern Neighbours Moritz Hütte, Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 99 Conclusions and Recommendations Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 103 Appendix 103 Abbreviations 104 The Authors Problems and Recommendations Jihadism in Africa: Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances The transnational terrorism of the twenty-first century feeds on local and regional conflicts, without which most terrorist groups would never have appeared in the first place. That is the case in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Syria and Iraq, as well as in North and West Africa and the Horn of Africa. -

Islamism After the Arab Spring: Between the Islamic State and the Nation-State the Brookings Project on U.S

Islamism after the Arab Spring: Between the Islamic State and the nation-state The Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World U.S.-Islamic World Forum Papers 2015 January 2017 Shadi Hamid, William McCants, and Rashid Dar The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide in- novative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institu- tion, its management, or its other scholars. Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World Center for Middle East Policy at Brookings Brookings recognizes that the value it provides to any supporter is in its absolute commitment to quality, 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW independence and impact. Activities supported by its Washington, DC 20036 donors reflect this commitment and the analysis and recommendations are not determined by any donation. www.brookings.edu/islamic-world STEERING n 2015, we returned to Doha for the views of the participants of the work- COMMITTEE the 12th annual U.S.-Islamic World ing groups or the Brookings Institution. MArtiN INDYK Forum. Co-convened annually by Select working group papers will be avail- Executive Ithe Brookings Project on U.S. Relations able on our website. Vice President with the Islamic World and the State of Brookings Qatar, the Forum is the premier inter- We would like to take this opportunity BRUCE JONES national gathering of leaders in govern- to thank the State of Qatar for its sup- Vice President ment, civil society, academia, business, port in convening the Forum with us. -

Street Medic Handbook for Occupy Chicago

Street Medic Handbook for Occupy Chicago and the mobilization against the 2012 NATO summit March 7, 2012 CURATED & DISTRIBUTED BY YOUR COMRADES AT THE PAPER REVOLUTION COLLECTIVE www.PaperRevolution.org FOR ADDITIONAL FREE STREET MEDIC RESOURCES VISIT US AT & DISTRIBUTE THIS LINK: www.PaperRevolution.org/Street-Medic-Guide i Foreward This is the first draft of a new approach to the street medic handbook. It is very much an experiment, adapting a variety of streetmedic and non-streetmedic material for use in the new wave of protest and rebellion sweeping the United States. Some of this material was originally intended to be used in Oaxaca, Tunisia, or Egypt, and needs further adaptation to the easily available foods, herbs, and medical realities of the urban United States. Future drafts will source all material that wasn’t written by the author, but this draft is being compiled and edited in a hurry, so that got left out. Please email any suggestions or comments on this manual to [email protected] creative commons attribution | non-commercial / non-corporate | share alike international – without copyright THIS STREET MEDIC GUIDE IS LICENSED UNDER CREATIVE COMMONS THIS GUIDE MAY BE SHARED, COPIED, ADAPTED, AND DISTRIBUTED FREELY FOR NON-COMMERCIAL PURPOSES WITH ADEQUATE ATTRIBUTION PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENT / DISCLAIMER NOTICE: THIS GUIDE IS NOT A REPLACEMENT FOR FIRST AID OR STREET MEDIC TRAINING. The information we provide within our street medic guide is intended to be used as reference material for educational purposes only. This resource in no way substitutes or qualifies an individual to act as a street medic without first obtaining proper training led by a qualified instructor. -

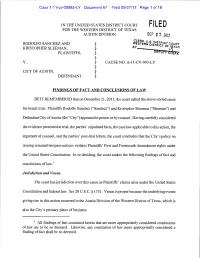

Sanchez and Western District Court § District 0 Kristopher Sleeman, § Plaintiffs, § § V

Case 1:11-cv-00993-LY Document 67 Filed 09/27/12 Page 1 of 18 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FILED FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS AUSTIN DIVISION SEP 2 7 2012 CLERK U.S. RODOLFO SANCHEZ AND WESTERN DISTRICT COURT § DISTRICT 0 KRISTOPHER SLEEMAN, § PLAINTIFFS, § § V. § CAUSE NO. A-1 1-CV-993-LY § CITY OF AUSTIN, § DEFENDANT. § FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW BE IT REMEMBERED that on December 21, 2011, the court called the above-styled cause for bench trial. Plaintiffs Rodolfo Sanchez ("Sanchez") and Kristopher Sleeman ("Sleeman") and Defendant City of Austin (the "City") appeared in person or by counsel. Having carefully considered the evidence presented at trial, the parties' stipulated facts, the case law applicable to this action, the argument of counsel, and the parties' post-trial letters, the court concludes that the City's policy on issuing criminal-trespass notices violates Plaintiffs' First and Fourteenth Amendment rights under the United States Constitution. In so deciding, the court makes the following findings of fact and conclusions of law.1 Jurisdiction and Venue The court has jurisdiction over this cause as Plaintiffs' claims arise under the United States Constitution and federal law. See 28 U.S.C. § 1331. Venue is proper because the underlying events giving rise to this action occurred in the Austin Division of the Western District of Texas, which is also the City's primary place of business. All findings of fact contained herein that are more appropriately considered conclusions of law are to be so deemed. Likewise, any conclusion of law more appropriately considered a finding of fact shall be so deemed. -

Mobilization Under Authoritarian Rule

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Cadmus, EUI Research Repository Bread, Freedom, Human Dignity The Political Economy of Protest Mobilization in Egypt and Tunisia Jana Warkotsch Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of Political and Social Sciences of the European University Institute Florence, August, 2014 submission European University Institute Department of Political and Social Sciences Bread, Freedom, Human Dignity The Political Economy of Protest Mobilization in Egypt and Tunisia Jana Warkotsch Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of Political and Social Sciences of the European University Institute Examining Board Professor Donatella della Porta, (EUI Supervisor) Professor Philippe Schmitter, European University Institute Professor Jeff Goodwin, New York University Professor Emma Murphy, Durham University © Jana Warkotsch, 2014 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people who accompanied me on the way to completing this thesis and who deserve my heartfelt gratitude. Institutionally, the EUI and my supervisor Donatella della Porta have provided me with the best environment in which to develop my research that I could have hoped for. Many of its scholars and students have provided valuable feedback along the way and its open academic culture allowed for exploring ideas across disciplinary boundaries. In addition, my jury consisting of Philippe Schmitter, Emma Murphy and Jeff Goodwin, provided insightful and thought provoking comments. Thanks also go to the many people that I have met and interviewed along the way, who have provided their time, insights, and personal stories. -

Libya's Untold Story: Civil Society Amid Chaos

Judith and Sidney Swartz Director and Professor of Politics Libya’s Untold Story: Civil Society Amid Shai Feldman Associate Director Chaos Kristina Cherniahivsky Charles (Corky) Goodman Professor Jean-Louis Romanet Perroux of Middle East History and Associate Director for Research Naghmeh Sohrabi wo Parliaments and two governments1—neither of Senior Fellow Abdel Monem Said Aly, PhD Twhich is exercising any significant control over people Goldman Senior Fellow and territory; two coalitions of armed groups confronting Khalil Shikaki, PhD one another and conducting multiple overlapping localized Myra and Robert Kraft Professor conflicts; thriving organized crime, kidnappings, torture, of Arab Politics Eva Bellin targeted killings, and suicide bombings; and an increasing Henry J. Leir Professor of the number of armed groups claiming affiliation to ISIS (also Economics of the Middle East known as Da’esh): These are powerful reasons to portray Nader Habibi Libya as the epitome of the failure of the Arab Spring. The Sylvia K. Hassenfeld Professor of Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies country is sliding into a civil war, and a functional Libyan Kanan Makiya state is unlikely to emerge anytime soon. By all measures and Neubauer Junior Research Fellow standards, the Libyan democratic transition appears to have Sarah El-Kazaz, PhD been derailed. Junior Research Fellows Hikmet Kocamaner, PhD Asher Orkaby, PhD Yet notwithstanding these sorry aspects of Libya’s transition, there is a slow, David Siddhartha Patel, PhD less visible, but more positive change occurring in the midst of the country’s Jean-Louis Romanet Perroux chaos. It is not a change that is happening at the level of state institutions, and it is hard to see its fruits in the short term. -

Austin Chronicle Page 1 of 3

Review: Patience - The Austin Chronicle Page 1 of 3 keyword SEARCH E-EDITION | LOG IN | REGISTER HOME NEWS FOOD MUSIC SCREENS ARTS BOOKS BLOGS CALENDAR SPECIAL PROMOTIONS ADS CLASSIFIEDS PERSONALS FOURTH OF JULY | HOT SAUCE FESTIVAL | PHOTO GALLERIES | RESTAURANT POLL | SUMMER CAMPS | CONTESTS | JOB OPENINGS FEATURED CONTENT news food music screens arts Occupy Austin Cool Off on The Grownup Lynn Shelton The Founding Occupies 7/4 – Lake Travis, Version of on the Process Fathers' First and Considers Enjoy Some Hill Fiddle Phenom Behind 'Your Declaration: Its Future Country Ruby Jane Sister's Sister' 'Let’s ’Roque!' Cuisine the arts Exhibitionism This Gilbert & Sullivan Society production has something for every connoisseur of READMORE comedy KEYWORDS FOR THIS STORY BY ADAM ROBERTS, FRI., JUNE 15, 2012 Patience, Gilbert & Sullivan Society of Austin, Ralph MacPhail Jr., Jeffrey Jones-Ragona, Meredith Ruduski, Holton Johnson, Arthur DiBianca, Janette Jones Patience Brentwood Christian School Performing Arts Center, 11908 MORE PATIENCE N. Lamar, 474-5664 Exhibitionism www.gilbertsullivan.org FRI., JUNE 18, 1999 Through June 17 Running time: 2 hr., 30 min. MORE ARTS REVIEWS Big Range Austin Dance Festival 2012, Program For some, patience is exactly what the doctor ordered when it A comes to an evening at the opera. But fear not, ye who run for the BRADF 2012's opener embraced the experimental but hills at the mere utterance of "Richard Wagner" – the Gilbert & showed deep thinking and skilled execution Sullivan Society of Austin possesses just the antidote for JONELLE SEITZ, FRI., JUNE 29, 2012 Walkürian gravitas. Theirs is a Patience of a frolicking sort, ALL ARTS REVIEWS » allegorized in the riotous operetta's title character.