Jake Ladlow Final Thesis 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mill End Millthrop 1 Sedbergh 1 LA10 5SJ Mill End

Mill End Millthrop 1 Sedbergh 1 LA10 5SJ Mill End Dating back to the 19th century, Mill End sits along a private driveway within a small community of similar properties at Millthrop, a short distance by car or level walk on foot from Sedbergh. This cleverly converted former mill building offers versatile accommodation across two floors which would suit either the permanent or secondary residence purchaser and provides good views of Winder Fell, part of Wainwright’s beloved Howgill range. Included in the sale are private fishing rights to the River Rawthey, direct access being available from the secluded, riverside garden here at Mill End. Just 5 miles from junction 37 of the M6 and 10 miles from Auld Grey town of Kendal, Sedbergh is well placed in terms of road access to both the Lake District and Yorkshire Dales national park. Public transport options are numerous with Oxenholme Main line only 10 miles away. Private and independent schooling for primary and secondary stages are easily accessible and a host of modern day amenities and open air, weekly market are available in Sedbergh, England’s official ‘book town’. Millthrop is on the famous Dales Way, an 80 mile walk from Ilkley to Bowness on Windermere, popular with tourists throughout the year. The accommodation at Mill End is currently set out over two floors with kitchen and bathroom facilities to each level. However, the layout does offer several options for re-working the existing design of the three bedrooms, two spacious bathrooms and two kitchens to suit the purchaser’s individual requirements and to make best use of the available space. -

15 Millthrop, Sedbergh, LA10 5SP £144,000 Your Chance to Own A

15 Millthrop, Sedbergh, LA10 5SP £144,000 Your chance to own a small traditional cottage with casement windows and beamed ceilings and all modern conveniences whilst retaining its character. Dedicated parking space. Auctioneers, Estate Agents & Property Managers 70, Main Street, Sedbergh, Cumbria LA10 5AD [email protected] www.chriswhelan.co.uk Tel: 015396 20293 Fax 015396 21650 Accommodation (All measurements are approximate) Stairs Up to half landing with door to garden then up again. Kitchen 1.83 x 1.98m (6ft 0ins x 6ft 6ins) Range of wall and base units with stainless steel 1 ½ Bathroom 2.41 x 2.11m (7ft 11ins x 6ft 11ins) bowl sink. Space for fridge and cooker. Tile splash. Panel bath with electric shower over. WC. Pedestal Tiled floor. Cupboard under stairs housing Vaillant basin. Tile splash. Radiator. Carpet. Combi gas boiler. Bedroom 2.84 x 3.66m (9ft 4ins x 12ft 0ins) Lounge/diner 3.43 x 3.61m (11ft 3ins x 11ft 10ins) Built in cupboard. Radiator. Carpet. Gas fired stove. Built in cupboard. Carpet. Radiator. Stairs up to Attic 3.91 x 3.48m (12ft 10ins x 11ft 5ins) Veluxe rooflight. Radiator. Carpet. Storage under eaves. Entrance Vestibule Directions From Sedbergh take the road towards Dent, cross the bridge over the River Rawthey then take first left to Millthrop. At the top of road turn right and follow road through hamlet. No 15 is on the right. Local Authorities: South Lakeland District Council, Kendal. Cumbria County Council, Carlisle Planning Authority: Yorkshire Dales National Park, Yoredale, Bainbridge, Leyburn. N.Yorkshire DL8 3EL. -

4-Night Western Yorkshire Dales Tread Lightly Guided Walking Holiday

4-Night Western Yorkshire Dales Tread Lightly Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Tread Lightly Destinations: Yorkshire Dales & England Trip code: SDSUS-4 2, 3 & 4 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW We are all well-versed in ‘leaving no trace’ but now we invite you to join us in taking it to the next level with our new Tread Lightly walks. We have pulled together a series of spectacular walks which do not use transport, reducing our carbon footprint while still exploring the best landscapes that the Western Yorkshire Dales have to offer. You will still enjoy the choice of three top-quality walks of different grades as well as the warm welcome of a HF country house, all with the added peace of mind that you are doing your part in protecting our incredible British countryside. Snuggled between the much-loved Lake District and the charming Yorkshire Dales lies the hidden beauty of the Howgill Fells. This corner of the Yorkshire Dales National Park offers high peaks, rugged dales, quaint market towns and sweeping panoramas, all of which can be enjoyed on our Guided Walking holidays. www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our country house • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • 3 days guided walking • Use of our comprehensive Discovery Point • Choice of up to three guided walks each walking day • The services of HF Holidays Walking Leaders HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Head out on guided walks to discover the varied beauty of the Yorkshire Dales on foot • Let an experienced leader bring classic routes and offbeat areas to life • Visit charming Dales villages • Look out for wildlife, find secret corners and learn about the Dales’ history • Evenings in our country house where you share a drink and re-live the day’s adventures TRIP SUITABILITY This trip is graded Activity Level 2, 3 and 4,. -

Yorkshire Dales National Park Local Plan 2015-2030 the Local Plan Was Adopted on 20 December 2016

Yorkshire Dales National Park Local Plan 2015-2030 The Local Plan was adopted on 20 December 2016. It does not cover the parts of Eden District, South Lakeland or Lancaster City that have been designated as part of the extended National Park from 1 August 2016. The Local Plan is accompanied by a series of policies maps that provide the spatial expression of some of the policies. The maps show land designations - for example, where land is protected for wildlife purposes. They also show where land is allocated for future development. The policies maps can be found on the Authority’s website in the Planning Policy section at www.yorkshiredales.org.uk/policies-maps 1 Introduction 1 L4 Demolition and alteration of 77 traditional farm buildings 2 Strategic Policies L5 Heritage assets - enabling 79 SP1 Sustainable development 10 development SP2 National Park purposes 12 L6 Crushed rock quarrying 81 SP3 Spatial strategy 14 L7 Building stone 85 SP4 Development quality 18 L8 Reworking mineral waste 86 SP5 Major development 21 L9 Mineral and railhead 87 safeguarding 3 Business & Employment L10 The open upland 89 BE1 Business development sites 24 BE2 Rural land-based enterprises 26 6 Tourism BE3 Re-use of modern buildings 28 T1 Camping 92 BE4 New build live/work units 30 T2 Touring caravan sites 94 BE5 High street service frontages 32 T3 Sustainable self-catering 96 BE6 Railway-related development 34 visitor accommodation BE7 Safeguarding employment 36 T4 Visitor facilities 99 uses T5 Indoor visitor facilities 101 4 Community 7 Wildlife C1 Housing -

S/03/704 Proposal: Full Planning Permission for Erection of 8 No

Gail Dent From: Judith Eastham REDACTED BY YDNPA Sent: 25 June 2020 21:26 To: Planning Subject: S/03/704 Dear Ms Clowes and Mr R Graham Planning Application Reference: S/03/704 Proposal: Full planning permission for erection of 8 No. dwellings, associated accesses, parking and landscaping. Address: Land opposite Derry Cottages, Millthrop, Sedbergh We are writing regarding the above planning application and wish to bring to your attention recent issues with the drains that have affected Derry Cottages, Millthrop. As you will be aware Derry Cottages is situated opposite the land for the proposed development of 8 dwellings. In our previous correspondence of 20 May 2020, we raised a question over sewage disposal as the proposed plans are non-committal as to which method will be used; our concern being that the existing sewage disposal system in the hamlet will be unable to cope with a further 8 properties. Our property, No. 1 The Derry had significant problems with the sewerage on 16 June 2020, as well as the properties at No.3 on 3 and 4 June 2020 and No.4 on 15 June 2020. The property at No.2 is presently unoccupied. It is these issues that we wish to bring to your attention as it further highlights the concerns that we raised on 20 May 2020. We have been unable to identify the cause of these blockages, but we have identified what appears to be a collapsed drain at the entrance to Blandses farm, which, we believe may be causing the problem as we did retrieve stones and debris from the blockage. -

Howgill), SD69SW (Firbank) and SD69SE (Sedbergh)

Geological notes and local details for 1:10 000 sheet SD69NE (Westerdale), and parts of sheets SD69NW (Howgill), SD69SW (Firbank) and SD69SE (Sedbergh) Part of 1: 50 000 sheets 39 (Kendal) and 40 (Kirkby Stephen) Geology and Landscape Northern Britain Programme Internal Report IR/03/090 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGY AND LANDSCAPE NORTHERN BRITAIN PROGRAMME INTERNAL REPORT IR/03/090 Geological notes and local details for 1:10 000 sheet SD69NE The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the (Westerdale), and parts of sheets Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Licence No: 100017897/2006. SD69NW (Howgill), SD69SW Keywords (Firbank) and SD69SE Report; Howgill Fells, stratigraphy, Ordovician, (Sedbergh) Silurian. Front cover Part of 1: 50 000 sheets 39 (Kendal) and 40 (Kirkby Stephen) Howgill Fells from the Midddleton Fells. (Photograph N H Woodcock) N H Woodcock, R B Rickards Bibliographical reference WOODCOCK, N H, RICKARDS, R B. 2006. Geological notes and local details for 1:10 000 sheet SD69NE (Westerdale), and parts of sheets SD69NW (Howgill), SD69SW (Firbank) and SD69SE (Sedbergh). British Geological Survey Internal Report, IR/03/090. 61pp. Copyright in materials derived from the British Geological Survey’s work is owned by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and/or the authority that commissioned the work. You may not copy or adapt this publication without first obtaining permission. Contact the BGS Intellectual Property Rights Section, British Geological Survey, Keyworth, e-mail [email protected]. You may quote extracts of a reasonable length without prior permission, provided a full acknowledgement is given of the source of the extract. -

The Dales Way Guided Trail

The Dales Way Guided Trail Tour Style: Guided Trails Destinations: Yorkshire Dales & England Trip code: MDLDD Trip Walking Grade: 4 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW The Dales Way was one of the earliest "unofficial" long distance routes. For most of its 79 miles it shuns the craggy tops and summit ridges to keep to the valley bottoms. It is, in essence, a riverside route linking existing rights of way to cross the Yorkshire Dales in a south-east to north-west direction. It connects the urban fringe of Ilkley to the shores of Windermere by way of Wharfedale, Dentdale and Eastern Lakeland. Wildlife is rich and varied: rivers provide habitat for a wide range of birds and the Wharfe is noted for its trout, often seen leaping out of the water on summer days. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our country house • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • The services of an HF Holidays' walks leader • All transport on walking days www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • The complete Dales Way from Ilkley to Bowness • Meander through beautiful Yorkshire Dales scenery • Stay at Newfield Hall, Malhamdale TRIP SUITABILITY This Guided Walking/Hiking Trail is graded 4 which involves walks /hikes over long distances in remote countryside and rough terrain. Sustained ascents and descents and occasional sections of scree and some steep ground are encountered. You will require a good level of fitness as you will be walking every day. It is your responsibility to ensure you have the relevant fitness and equipment required to join this holiday. -

351 February 2017

Sedbergh & District February 2017 Issue 351 Donation £1 A very warm welcome to all our A massive thank you to all the readers and contributors and a contributors of text this month. We Healthy and Happy New Year to you think it is probably the most ever all. By the time you read this, we are received. It just shows that there is 1/12th through the year!! Where is lots going on in our community. the time going? Dennis & Jacky Whicker Jill Colquhoun Exhibition until Sunday 4th March A beautiful new exhibition from local artist Jill, who is inspired by nature and the landscape of Cumbria and the Yorkshire Dales. The main emphasis of Jill's work is vibrancy, pattern, and movement in nature. To achieve this, she has developed a novel method of combining wax resist batik techniques with acrylic paint The resulting paintings are unique and rich in style and colour. Celebrating Ceramics until Sunday 4th March A group of 12 ceramacists from Cumbria and North Yorkshire displaying a wide range of work, from decorative pieces, to practical crockery, and some beautiful ceramic wall art. A must see for any pottery enthusiast. Open 10.30-4.30 adults: £3.50, concs: £3, children: FREE FREE ENTRY for LA10 residents on Sundays www.farfieldmill.org 015396 21958 CLOSING DATES: NEW ADVERTS - 15th; OTHERWISE - 19th S & D Lookaround 72 Main Street, Sedbergh LA10 5AD Telephone 015396 - 21960 e-mail: [email protected] ~ Web Site: http://www.sedberghlookaround.org.uk Table of Articles Bed & Breakfast 108 Garsdale Carol Singing 24 Bus Time Tables -

383 December 2019

Sedbergh & District December 2019 Issue 383 Donation £1 Happy Christmas and a very and purpose. Please let us know prosperous 2020 to everyone in your opinions, what we need to Sedbergh and District. maintain, and what we need to Well, we’ve now produced a full change. year of Lookaround, and hopefully Thank you to all who continue to have kept it true to it’s original spirit support us! Ed. CLOSING DATE: 15th of every month for everything S & D Lookaround 72 Main Street, Sedbergh LA10 5AD Mobile: 07464 - 895425 e-mail: [email protected] ~ Web Site: http://www.sedberghlookaround.org.uk Articles A Tribute To The Late Jean Dixon 71 Ladies NFU Coffee Morning 41 A View From the Fells (Cartoon) 78 Lakeland Voice 26 A Year At The Peoples’ Hall 73 News From The Pews 9 Apple Day 67 News From The Pews Dent With Cowgill. 8 Art Society 23 October Weather 38 Autumn's Rhythm 34 Orchestra Concert 27 B4RN For Marthwaite And Howgill 50 People’s Hall News 74 B4RN For Sedbergh Town 51 Poppy Appeal 2019. 7 Bowling Club 15 Pride 15 Boxes Of Hope Cumbria 45 Public Transport In Rural Areas 77 Charity Girls Jumble Sale For M.S. 71 Safe Fancy Dress Costumes 70 Community Charity Shop 60 Sandra W Longlands 60th Birthday 76 Community Swifts 37 Sedbergh Parish Council 30 Community Volunteers Sought 74 Sedbergh School News 42 Councillor’s Corner 33 Settlebeck – “ A Night To Remember “ 44 Crime Update For November 2019 76 Sight Advice South Lakes 58 Dalesman Veterans’ Offer 54 December Family Musings 39 Spring Show 68 Dementia Action Alliance 55 St Andrews Coffee Mornings 66 Dentdale - Head To Foot 41 Thanks 75 The Holly And The Ivy And Other Christmas Dentdale Christian Fellowship 12 5 Plants Embodied Mind – Mindful Body 14 Tim’s Column 28 Environmental Network 63 Flicks In The Fells 75 Town Band 28 Funded Electric Vehicle Charge Points 52 W.D.B. -

Yorkshire Weekender

The Dales Way Association. PO Box 1065, Bradford, BD1 9JY. [email protected] www.dalesway.org.uk Newsletter Number 40 Autumn 2011 Editorial It has always been one of the aims of the Dales Way Association to eliminate road-walking as far as possible from the route of the Dales Way. One short section of minor, but busy road has exercised our minds for many years, the stretch from Sprint Bridge to Hall Lane, which leads into Burneside. The obvious solution would be a footpath over the wall on the south side of the road and parallel to it. In 2006 an attempt was made to create such a footpath, but nothing came of it. In 2010 Cumbria County Council started another initiative, but again, fifteen months later, no progress had been made. In August of this year the Association requested the help of Chris Holland, South Lakeland District Councillor. He responded within 48 hours and progress since then has been rapid. The land is owned by the Cropper Estate (Croppers also own the paper mill in Burneside). Chris has already had a meeting with Mr Cropper, who is sympathetic to our request, but he has not yet spoken to the tenant farmer at Burneside Hall, whose agreement would also be necessary. Chris and committee member Donald Holland have walked the proposed path in order to assess the cost of the gates and stiles required. The Dales Way Association has agreed to contribute to these costs and we thank Chris for his help and enthusiasm in moving to solve a 40 year old problem. -

7-Night Western Yorkshire Dales Guided Walking Holiday

7-Night Western Yorkshire Dales Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Guided Walking Destinations: Yorkshire Dales & England Trip code: SDBOB-7 2, 3 & 4 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Snuggled between the much-loved Lake District and the charming Yorkshire Dales lies the hidden beauty of the Howgill Fells. This corner of the Yorkshire Dales National Park offers high peaks, rugged dales, quaint market towns and sweeping panoramas, all of which can be enjoyed on our Guided Walking holidays. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our country house • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • 5 days guided walking and 1 free day • Use of our comprehensive Discovery Point • Choice of up to three guided walks each walking day • The services of HF Holidays Walking Leaders www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Head out on guided walks to discover the varied beauty of the Yorkshire Dales on foot • Let an experienced leader bring classic routes and offbeat areas to life • Visit charming Dales villages • Look out for wildlife, find secret corners and learn about the Dales’ history • Evenings in our country house where you share a drink and re-live the day’s adventures TRIP SUITABILITY This trip is graded Activity Level 2, 3 and 4,. Explore the beautiful Yorkshire Dales and Howgill Fells on our guided walks. We offer a great range of walks to suit everyone - including gentle walks along the green valleys, as well as opportunities to climb to the summits of Ingleborough, Whernside and the Howgill Fells. -

20000947.Pdf

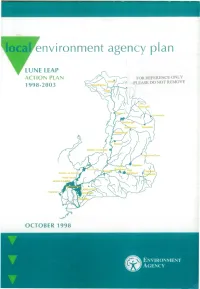

local ^environment agency plan LUNE LEAP ACTION PLAN FOR REFERENCE ONLY 1998-2003 PLEASE DO NOT REMOVE Grl sedate Chape l-le-Dale Carnforth Bolton-le-Sand' f { Hest Bank, MORECAMB Heysham OCTOBER 1998 ▼------------------------- — E n v iro n m en t \n u p l Ag en c y T 50 60 70 80 Lune Local Environment Agency Plan Map 1 E n v i r o n m e n t A g e n c y 40 f 10 10 ... Orton P w b LAKE DISTRICT J 1 V \ ,~'7 NATIONAL PARK \.*^s,Gra«nholi P 0C **\TV &_ i„0e fry #/ Tebay,’Af./ Oo I \I 5^ / \ \ / v-v, \\ \AV Pnr I\ If/ 7 /*y kU I f) J NY EDEiu dc x ) \ ..a a 00 / IS? ) *-°w / *sv /a, DovlMQijU^Sa//£\ SD ) V SecfcN > Lune Infrastructure showing Local Authority Boundaries KEY Area Boundary Main Watercourse 90 90 Minor Watercourse Canal Local Authority Boundary — Motorways ----- A Roads 80 Swarth Beck Low __ | Bentham Hjflh $i J ) Clapham 70 Morecambe Bay Bentham r'J*/ Austwiok 70 Carnforth E3ec*\^ Hofnby Bolton-le-iBolton-le-Sands,/^ $ /fl/SH SC/A Hest Ban Secvf CRAVEN & DC MORECAMBE . -ANCASTEf \D e n n y cour Torrisholpoe S eek ^ o*c/7i c ■W ■ } o Heysham UAfJC/STER A 60 Dtforth/ 60 I BurlowBern o Alt J N A o V L u n e E stu a ry 10km _J 50 60 70 80 KEY DETAILS General Plan Area 1223 sq.kms Flood Defence Length of Main River 105 km Planning Authorities Total number o f planning authorities within the plan area Conservation Total number o f Sites o f Special Scientific Interest 14 Designated Sites of nature conservation value 4 Areas o f Ancient Woodland 9 Water Resources Long-Term (1961-1991) overall catchment average rainfall 1435mm Total