Eggsercizer — “The World’S Smallest Exercise Machine” 243 Case 12: Decision Support for Stage–Gate Processes 273

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Repair Manual

Repair Manual Showing Short Cuts and Methods for Repairing and Upkeep Durant and Star Cars FOUR CYLINDER MODELS JANUARY, 1929 DURANT MOTORS, Inc. BROADWAY AT 57th STREET NEW YORK CITY DURANT MOTOR CO. of NEW JERSEY DURANT MOTOR CO. of MICHIGAN Elizabeth, N. J. Lansing, Michigan DURANT MOTOR CO. of CALIFORNIA DURANT MOTOR CO. of CANADA, LTD. Oakland, Cal. Toronto (Leaside), Ontario 1 Blank page 2 WARRANTY E warrant each new DURANT and STAR motor vehicle so by us to be free from defects in material W under normal use and service, our obligation under this warranty being limited to making good at our factory any part or parts thereof which shall with ninety (90) days after delivery of such vehicle to the original purchaser be returned to us, transportation charges prepaid, and which our examination shall disclose to our satisfaction to have been thus defective, this warranty being expressly in lieu of all other warranties expressed or implied and of all other obliga- tions or liabilities on our part. This warranty shall not apply to any vehicle which shall have been repaired or altered outside of our factory in any way, so as in our judgment, to affect its stability or reliability, nor which has been subject to misuse, negligence or accident. We make no warranty whatever in respect to tires, rims, ignition apparatus, horns or other signaling devices, starting devices, generators, batteries, speedometers or other trade accessories, inasmuch as they are usually warranted separately by their respective manufacturers. We do not make any guarantee against, and we assume no responsibility for, any defect in metal or other material, or in any part, device, or trade accessory that cannot be dis- covered by ordinary factory inspection. -

Cloud-Based Visual Discovery in Astronomy: Big Data Exploration Using Game Engines and VR on EOSC

Novel EOSC services for Emerging Atmosphere, Underwater and Space Challenges 2020 October Cloud-Based Visual Discovery in Astronomy: Big Data Exploration using Game Engines and VR on EOSC Game engines are continuously evolving toolkits that assist in communicating with underlying frameworks and APIs for rendering, audio and interfacing. A game engine core functionality is its collection of libraries and user interface used to assist a developer in creating an artifact that can render and play sounds seamlessly, while handling collisions, updating physics, and processing AI and player inputs in a live and continuous looping mechanism. Game engines support scripting functionality through, e.g. C# in Unity [1] and Blueprints in Unreal, making them accessible to wide audiences of non-specialists. Some game companies modify engines for a game until they become bespoke, e.g. the creation of star citizen [3] which was being created using Amazon’s Lumebryard [4] until the game engine was modified enough for them to claim it as the bespoke “Star Engine”. On the opposite side of the spectrum, a game engine such as Frostbite [5] which specialised in dynamic destruction, bipedal first person animation and online multiplayer, was refactored into a versatile engine used for many different types of games [6]. Currently, there are over 100 game engines (see examples in Figure 1a). Game engines can be classified in a variety of ways, e.g. [7] outlines criteria based on requirements for knowledge of programming, reliance on popular web technologies, accessibility in terms of open source software and user customisation and deployment in professional settings. -

Rulemaking: 1999-10 FSOR Emission Standards and Test Procedures

State of California Environmental Protection Agency AIR RESOURCES BOARD EMISSION STANDARDS AND TEST PROCEDURES FOR NEW 2001 AND LATER MODEL YEAR SPARK-IGNITION MARINE ENGINES FINAL STATEMENT OF REASONS October 1999 State of California AIR RESOURCES BOARD Final Statement of Reasons for Rulemaking, Including Summary of Comments and Agency Response PUBLIC HEARING TO CONSIDER THE ADOPTION OF EMISSION STANDARDS AND TEST PROCEDURES FOR NEW 2001 AND LATER MODEL YEAR SPARK-IGNITION MARINE ENGINES Public Hearing Date: December 10, 1998 Agenda Item No.: 98-14-2 I. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ........................................................................................ 3 II. SUMMARY OF PUBLIC COMMENTS AND AGENCY RESPONSES – COMMENTS PRIOR TO OR AT THE HEARING .................................................................................................................. 7 A. EMISSION STANDARDS ................................................................................................................... 7 1. Adequacy of National Standards............................................................................................. 7 2. Lead Time ................................................................................................................................. 8 3. Technological Feasibility ........................................................................................................ 13 a. Technological Feasibility of California-specific Standards ..............................................................13 -

The Video Game Industry an Industry Analysis, from a VC Perspective

The Video Game Industry An Industry Analysis, from a VC Perspective Nik Shah T’05 MBA Fellows Project March 11, 2005 Hanover, NH The Video Game Industry An Industry Analysis, from a VC Perspective Authors: Nik Shah • The video game industry is poised for significant growth, but [email protected] many sectors have already matured. Video games are a large and Tuck Class of 2005 growing market. However, within it, there are only selected portions that contain venture capital investment opportunities. Our analysis Charles Haigh [email protected] highlights these sectors, which are interesting for reasons including Tuck Class of 2005 significant technological change, high growth rates, new product development and lack of a clear market leader. • The opportunity lies in non-core products and services. We believe that the core hardware and game software markets are fairly mature and require intensive capital investment and strong technology knowledge for success. The best markets for investment are those that provide valuable new products and services to game developers, publishers and gamers themselves. These are the areas that will build out the industry as it undergoes significant growth. A Quick Snapshot of Our Identified Areas of Interest • Online Games and Platforms. Few online games have historically been venture funded and most are subject to the same “hit or miss” market adoption as console games, but as this segment grows, an opportunity for leading technology publishers and platforms will emerge. New developers will use these technologies to enable the faster and cheaper production of online games. The developers of new online games also present an opportunity as new methods of gameplay and game genres are explored. -

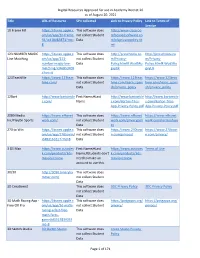

Digital Resources Approved for Use in Academy District 20 As Of

Digital Resources Approved for use in Academy District 20 as of August 20, 2021 Title URL of Resource SPII collected Link to Privacy Policy Link to Terms of Service 10 Frame Fill https://itunes.apple.c This software does http://www.classroo om/us/app/10-frame- not collect Student mfocusedsoftware.co fill/id418083871?mt= Data m/cfsprivacypolicy.ht 8 ml 123 NUMBER MAGIC https://itunes.apple.c This software does http://preschoolu.co http://preschoolu.co Line Matching om/us/app/123- not collect Student m/Privacy- m/Privacy- number-magic-line- Data Policy.html#.Wud5Ro Policy.html#.Wud5Ro matching/id46853409 gvyUk gvyUk 4?mt=8 123TeachMe https://www.123teac This software does https://www.123teac https://www.123teac hme.com/ not collect Student hme.com/learn_spani hme.com/learn_spani Data sh/privacy_policy sh/privacy_policy 12Bart http://www.bartontile First Name;#Last http://www.bartontile http://www.bartontile s.com/ Name s.com/Barton-Tiles- s.com/Barton-Tiles- App-Privacy-Policy.pdf App-Privacy-Policy.pdf 2080 Media https://www.nfhsnet This software does https://www.nfhsnet https://www.nfhsnet Inc/PlayOn Sports work.com/ not collect Student work.com/privacypoli work.com/termsofuse Data cy 270 to Win https://itunes.apple.c This software does https://www.270towi https://www.270towi om/us/app/270towin/ not collect Student n.com/privacy/ n.com/privacy/ id483161617?mt=8 Data 3 DS Max https://www.autodes First Name;#Last https://www.autodes Terms of Use k.com/products/3ds- Name;#Students don't k.com/products/3ds- max/overview need to make an max/overview account to use this. -

Rapid, Continuous Movement Between Nodes As an Accessible Virtual

Rapid, continuous movement between nodes as an accessible virtual reality locomotion technique HABGOOD, Jacob <http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4531-0507>, MOORE, David, WILSON, David and ALAPONT, Sergio Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/18594/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version HABGOOD, Jacob, MOORE, David, WILSON, David and ALAPONT, Sergio (2018). Rapid, continuous movement between nodes as an accessible virtual reality locomotion technique. In: IEEE VR 2018 Conference. IEEE, 371-378. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Rapid, Continuous Movement Between Nodes as an Accessible Virtual Reality Locomotion Technique M. P. Jacob Habgood* David Moore David Wilson Sergio Alapont Steel Minions Game Studio Steel Minions Game Studio Steel Minions Game Studio Steel Minions Game Studio Sheffield Hallam University Sheffield Hallam University Sheffield Hallam University Sheffield Hallam University ABSTRACT The confounding effect of player locomotion on the vestibulo- In this paper, we examine an approach to locomotion which ocular reflex is one of the principal causes of motion sickness in maintains users’ continuity of motion by making rapid, continuous immersive virtual reality. Continuous motion is particularly movements between nodal waypoints. The motion is made at a problematic for stationary user configurations, and teleportation fast, linear velocity with instant acceleration and deceleration. has become the prevailing approach for providing accessible Continuous movements made with ‘real-world’ speeds and locomotion. -

T I S ^ E ' Cottons CUSTOMIZED KITCHENS 0^

: : ' I '■ ;:'vV WEDKBBDAY, FEBRUARY 2,.lO li' JL ffba Wahtlkir tfnnrlrrBtpr Eurntog frrtJh Avenga Dnflr KsC Prsss Ron I at P. a WsaBSa rue tha fairth •« ill- •■t. iWk t \ ^ 9 , 6 8 0 lawet by aaow aarty FtMay; e of «ka AniH FYMay, mow amy ebaago «a i lul Town / I V. ManehtSner— A tity of Vittage Charm midbi t I m k Pwxda’t Vuflon nMOtben t» iDMt tUa ave* MANCHESTER, CONN„ THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 3,1949 PRKJE FOUR CENTS StatTjO at the 8^^" VOL. LX \T n„ NO. 105 (TWENTY PAGES) AtMy cltaC^l. where they wli) SMART YOUNO H O ifB M leave for a lobogfan party. 'I ( . ■ ■ The 0* Troop 16, Olrl President Congratulates Retiring Generals floouta, wm ba omitted thto week. ENTIRTAIN IN Sharp Partisan Rows The next meeting held World Gets Notice . Thuraday, Fhbniary 10, under the l c a ! 3 e ^ 0* Mia. Lealle Hoyt and SaT^tawrence MacQUpln, In T IA P A R T Y St. Jamaa’a adUwl hall. RedMove Will Not •In Senate and House An Important btialneae meeting a t the CoamopoHtan Club will b e , held Friday attemoon at two Be Let Hurt Unity o'clock In the Federation room of j center church houae, when the | mambera will vote on the revtaed i On Budget, Housing by-lawa. A talk on the “Ro- Real ^Significance Seen ^nen of Silver” wlU foUow the, Norway’s Own — Imalneaa aenlon, and a large at In Acheson’s Rejec tendance of merabera le hoped for. tion of Stalin’s' Lat Democratic Floor Lead Mra. -

A1.1 Strategy & Leadership

INSTITUTE OF CERTIFIED PUBLIC ACCOUNTANTS OF RWANDA CPA A1.1 STRATEGY & LEADERSHIP Study Manual 2nd edition February 2020, INSTITUTE OF CERTIFIED PUBLIC ACCOUNTANTS OF RWANDA Advanced Level A1.1 STRATEGY & LEADERSHIP 2nd Edition February 2020 This Manual has been fully revised and updated in accordance with the current syllabus/ curriculum. It has been developed in consultation with experienced tutors and lecturers. © ICPAR All copy right reserved All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of ICPAR. Acknowledgement We wish to officially recognize all parties who contributed to revising and updating this Manual, Our thanks are extended to all tutors and lecturers from various training institutions who actively provided their input toward completion of this exercise and especially the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning (MINECOFIN) through its PFM Basket Fund which supported financially the execution of this assignment Table Of Contents Units Title Page Introduction to the Course 6 1. Strategy process 9 Strategic Management and Operational Management 20 Perspectives on Strategy 22 The Marketing Dimension 22 The leadership and strategy leadership 48 2. The environment scanning and strategy position 53 Environmental Analysis 53 Assessing Strategic Capability 58 Measuring Stakeholder Expectations 63 3. Strategic choices 71 Corporate Level 71 Business Level 76 Strategy Development 83 4. Strategy implimentation and evaluation 87 Structure and Processes 87 Managing Key Enablers 95 Managing the Change Process 122 Understanding Groups and Teamwork 128 Organisational Communications 137 Project Management 143 Post stratgy evalution 150 5. -

Sustainability Report

Consolidated non-fi nancial 2019 statement pursuant to Legislative Decree No. 254 of 30th December 2016 Sustainability Report Dichiarazione consolidata di carattere non fi nanziario non fi consolidata di carattere Dichiarazione 2019 Unione di Banche Italiane Joint Stock Company in abbreviated form UBI Banca Spa Head Office and General Management: Piazza Vittorio Veneto 8, Bergamo (Italy) Operating offices: Bergamo, Brescia and Milan Member of the Interbank Deposit Protection Fund and the National Guarantee Fund Belonging to the IVA UBI Group with VAT No. 04334690163 Tax Code, VAT No. and Bergamo Company Registration No. 03053920165 ABI 3111.2 Register of Banks No. 5678 Register of Banking Groups No. 3111.2 Parent company of the Unione di Banche Italiane Banking Group Share capital as at 31st December 2019: EUR 2,843,177,160.24 fully paid up PEC address: [email protected] www.ubibanca.it This document has been written with no account taken of the public exchange offer on all the Bank’s shares launched by Intesa SanPaolo S.p.A. on 17th February 2020. The images reproduced in this document have been taken from the book entitled “Le nostre immagini, la nostra immagine” published by Mondadori in March 2020, which contains a collection of photos taken by Group employees in the photographic competition of the same name held in 2019. On the front cover: Oscar Babucci – Val di Chiana Consolidated non-financial statement pursuant to Legislative Decree No. 254 of 30th December 2016 Sustainability Report 2019 Letter to our Stakeholders Ever since its foundation, UBI has been very aware of and focused on sustainability issues. -

Technical Energy Audit New Mexico State University Professional Services Contract #201302796-A

Prepared for New Mexico State University Las Cruces, New Mexico Technical Energy Audit Professional Services Contract #201302796-A January 31, 2014 Technical Energy Audit New Mexico State University Professional Services Contract #201302796-A January 31, 2014 Prepared for New Mexico State University Las Cruces, New Mexico Presented by: Michael Boyer Mailing Address: Account Executive 60 East Rio Salado Parkway, Suite 1001 Ameresco, Inc. Tempe, Arizona 85281 P: 801.425.3421 Local Office: E: [email protected] 6100 Foulois Road, Building 737 Hill Air Force Base, Utah 04856 Technical Energy Audit Executive Summary Ameresco, Inc. (Ameresco) is pleased to submit this Technical Energy Audit (TEA) to New Mexico State University (NMSU). Based on our site visits, work, and observations throughout the Las Cruces campus, this TEA provides recommended energy conservation measures (ECMs) that would reduce energy and operational costs at 45 campus buildings and campus wide facilities. Ameresco developed this TEA based on NMSU’s Professional Services Contract #201302796-A and Ameresco’s site visits, workshops, and utility analysis and energy calculations. This TEA is intended to provide an overall representation of the potential for energy and operational savings at NMSU. Based on the data collected from site surveys, facility interviews, and other means, Ameresco identified several ECMs that could help NMSU reduce overall operational costs. ES.1 Energy Conservation Measures ECMs found to have the best financial performance or are high priorities for NMSU include: • ECM 1: Interior Lighting • ECM 2: Exterior Lighting • ECM 3: Exterior Pole Mounted Lighting • ECM 6: Retrocommissioning • ECM 7: Variable Air Volume Retrofit • ECM 10: Economizer Upgrade or Repair • ECM 12: Chilled Water Pump Bypass • ECM 26: Satellite Plant Energy Savings • ECM 28: MyEnergyPro™-OpsPRO • ECM 29: MyEnergyPro™-DashPRO • ECM 30: MyEnergyPro™-Optimization Model ES.2 Savings Total projected savings from implementing these ECMs are $1,278,725. -

Participatory Gaming Culture

Master thesis Participatory gaming culture: Indie game design as dialogue between player & creator Martijn van Best student ID: 3175421 [email protected] New Media Studies Faculty of Humanities UTRECHT UNIVERSITY Course code: 200700088 THE-Scriptie / MA NMDC Supervisor: Erna Kotkamp Second reader: René Glas DATE: March 28th, 2011 1 To Mieke 2 Abstract In this thesis I argue that the current dichotomy between indie game design and mainstream design based on commercial appeal versus creative audacity is non-constructive. Instead, I wish to investigate to what extent indie game designers are able to establish a personal dialogue with their audience through their game. I frame independent game design as a participatory culture in which indies alter and modify existing game design conventions through a practice called abusive game design. This is a concept developed by Douglas Wilson and Miguel Sicart. Players who wish to master (partially) abusive games, need to learn about the designer's intentions rather than the game system. I argue that a designer's visibility in this way allows for a dialogue between creator and player. However, in a case study of indie title Super Crate Box (2010), it appears that in order to maintain a sense of fun, certain conventions of mainstream game design need to be adhered to. Indie designers, who often have the most visible and personal relationship with their audience, need to navigate between their wish for a personal connection with players and user friendly, but 'faceless' design. Scaling the tipping point too much to the abusive side instead of the conventional one, may be counter to designers' wishes to create an enjoyable game. -

Dissertation Pieces

Information-intensive innovation: the changing role of the private firm in the research ecosystem through the study of biosensed data By Elaine M Sedenberg A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Information Management and Systems in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Deirdre Mulligan, Co-Chair Professor John Chuang, Co-Chair Professor AnnaLee (Anno) Saxenian Professor Coye Cheshire Summer 2019 Information-intensive innovation: the changing role of the private firm in the research ecosystem through the study of biosensed data Copyright 2019 by Elaine M Sedenberg 1 Abstract Information-intensive innovation: the changing role of the private firm in the research ecosystem through the study of biosensed data by Elaine M Sedenberg Doctor of Philosophy in Information Management and Systems University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Deirdre Mulligan, Co-Chair Professor John Chuang, Co-Chair In a world instrumented with smart sensors and digital platforms, some of our most intimate and information-rich data are being collected and curated by private companies. The opportunities and risks derived from potential knowledge carried within these data streams are undeniable, and the clustering of data within the private sector is challenging traditional data infrastructures and sites of research. The role of private industry in research and development (R&D) has traditionally been limited— especially for earlier stage research—given the high risk, long time horizons, and uncertain returns on investment. However, the information economy has changed the way Silicon Valley and other technology firms operate their business models, which has vast implications for how they respectively innovate.