Conference Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Logophoricity in Finnish

Open Linguistics 2018; 4: 630–656 Research Article Elsi Kaiser* Effects of perspective-taking on pronominal reference to humans and animals: Logophoricity in Finnish https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2018-0031 Received December 19, 2017; accepted August 28, 2018 Abstract: This paper investigates the logophoric pronoun system of Finnish, with a focus on reference to animals, to further our understanding of the linguistic representation of non-human animals, how perspective-taking is signaled linguistically, and how this relates to features such as [+/-HUMAN]. In contexts where animals are grammatically [-HUMAN] but conceptualized as the perspectival center (whose thoughts, speech or mental state is being reported), can they be referred to with logophoric pronouns? Colloquial Finnish is claimed to have a logophoric pronoun which has the same form as the human-referring pronoun of standard Finnish, hän (she/he). This allows us to test whether a pronoun that may at first blush seem featurally specified to seek [+HUMAN] referents can be used for [-HUMAN] referents when they are logophoric. I used corpus data to compare the claim that hän is logophoric in both standard and colloquial Finnish vs. the claim that the two registers have different logophoric systems. I argue for a unified system where hän is logophoric in both registers, and moreover can be used for logophoric [-HUMAN] referents in both colloquial and standard Finnish. Thus, on its logophoric use, hän does not require its referent to be [+HUMAN]. Keywords: Finnish, logophoric pronouns, logophoricity, anti-logophoricity, animacy, non-human animals, perspective-taking, corpus 1 Introduction A key aspect of being human is our ability to think and reason about our own mental states as well as those of others, and to recognize that others’ perspectives, knowledge or mental states are distinct from our own, an ability known as Theory of Mind (term due to Premack & Woodruff 1978). -

Layers and Operators in Lakota1 Avelino Corral Esteban Universidad Autónoma De Madrid

Kansas Working Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 36 (2015), 1-33 Layers and operators in Lakota1 Avelino Corral Esteban Universidad Autónoma de Madrid Abstract Categories covering the expression of grammatical information such as aspect, negation, tense, mood, modality, etc., are crucial to the study of language universals. In this study, I will present an analysis of the syntax and semantics of these grammatical categories in Lakota within the Role and Reference Grammar framework (hereafter RRG) (Van Valin 1993, 2005; Van Valin and LaPolla 1997), a functional approach in which elements with a purely grammatical function are treated as ´operators`. Many languages mark Aspect-Tense- Mood/Modality information (henceforth ATM) either morphologically or syntactically. Unlike most Native American languages, which exhibit an extremely complex verbal morphological system indicating this grammatical information, Lakota, a Siouan language with a mildly synthetic / partially agglutinative morphology, expresses information relating to ATM through enclitics, auxiliary verbs and adverbs, rather than by coding it through verbal affixes. 1. Introduction The organisation of this paper is as follows: after a brief account of the most relevant morpho- syntactic features exhibited by Lakota, Section 2 attempts to shed light on the distinction between lexical words, enclitics and affixes through evidence obtained in the study of this language. Section 3 introduces the notion of ´operator` and explores the ATM system in Lakota using RRG´s theory of operator system. After a description of each grammatical category, an analysis of the linear order exhibited by the Lakota operators with respect to the nucleus of the clause are analysed in Section 4, showing that this ordering reflects the scope relations between the grammatical categories conveyed by these operators. -

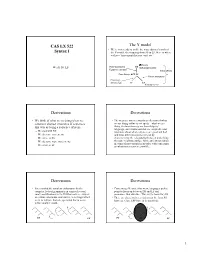

CAS LX 522 Syntax I the Y Model

CAS LX 522 The Y model • We’re now ready to tackle the most abstract branch of Syntax I the Y-model, the mapping from SS to LF. Here is where we have “movement that you can’t see”. θ Theory Week 10. LF Overt movement, DS Subcategorization Expletive insertion X-bar theory Case theory, EPP SS Covert movement Phonology/ Morphology PF LF Binding theory Derivations Derivations • We think of what we’re doing when we • The steps are not necessarily a reflection of what construct abstract structures of sentences we are doing online as we speak—what we are this way as being a sequence of steps. doing is characterizing our knowledge of language, and it turns out that we can predict our – We start with DS intuitions about what sentences are good and bad – We do some movements and what different sentences mean by – We arrive at SS characterizing the relationship between underlying – We do some more movements thematic relations, surface form, and interpretation in terms of movements in an order with constraints – We arrive at LF on what movements are possible. Derivations Derivations • It seems that the simplest explanation for the • Concerning SS, under this view, languages pick a complex facts of grammar is in terms of several point to focus on between DS and LF and small modifications to the DS that each are subject pronounce that structure. This is (the basis for) SS. to certain constraints, sometimes even things which • There are also certain restrictions on the form SS seem to indicate that one operation has to occur has (e.g., Case, EPP have to be satisfied). -

(2012) Perspectival Discourse Referents for Indexicals* Maria

To appear in Proceedings of SULA 7 (2012) Perspectival discourse referents for indexicals* Maria Bittner Rutgers University 0. Introduction By definition, the reference of an indexical depends on the context of utterance. For ex- ample, what proposition is expressed by saying I am hungry depends on who says this and when. Since Kaplan (1978), context dependence has been analyzed in terms of two parameters: an utterance context, which determines the reference of indexicals, and a formally unrelated assignment function, which determines the reference of anaphors (rep- resented as variables). This STATIC VIEW of indexicals, as pure context dependence, is still widely accepted. With varying details, it is implemented by current theories of indexicali- ty not only in static frameworks, which ignore context change (e.g. Schlenker 2003, Anand and Nevins 2004), but also in the otherwise dynamic framework of DRT. In DRT, context change is only relevant for anaphors, which refer to current values of variables. In contrast, indexicals refer to static contextual anchors (see Kamp 1985, Zeevat 1999). This SEMI-STATIC VIEW reconstructs the traditional indexical-anaphor dichotomy in DRT. An alternative DYNAMIC VIEW of indexicality is implicit in the ‘commonplace ef- fect’ of Stalnaker (1978) and is formally explicated in Bittner (2007, 2011). The basic idea is that indexical reference is a species of discourse reference, just like anaphora. In particular, both varieties of discourse reference involve not only context dependence, but also context change. The act of speaking up focuses attention and thereby makes this very speech event available for discourse reference by indexicals. Mentioning something likewise focuses attention, making the mentioned entity available for subsequent dis- course reference by anaphors. -

Minimal Pronouns, Logophoricity and Long-Distance Reflexivisation in Avar

Minimal pronouns, logophoricity and long-distance reflexivisation in Avar* Pavel Rudnev Revised version; 28th January 2015 Abstract This paper discusses two morphologically related anaphoric pronouns inAvar (Avar-Andic, Nakh-Daghestanian) and proposes that one of them should be treated as a minimal pronoun that receives its interpretation from a λ-operator situated on a phasal head whereas the other is a logophoric pro- noun denoting the author of the reported event. Keywords: reflexivity, logophoricity, binding, syntax, semantics, Avar 1 Introduction This paper has two aims. One is to make a descriptive contribution to the crosslin- guistic study of long-distance anaphoric dependencies by presenting an overview of the properties of two kinds of reflexive pronoun in Avar, a Nakh-Daghestanian language spoken natively by about 700,000 people mostly living in the North East Caucasian republic of Daghestan in the Russian Federation. The other goal is to highlight the relevance of the newly introduced data from an understudied lan- guage to the theoretical debate on the nature of reflexivity, long-distance anaphora and logophoricity. The issue at the heart of this paper is the unusual character of theanaphoric system in Avar, which is tripartite. (1) is intended as just a preview with more *The present material was presented at the Utrecht workshop The World of Reflexives in August 2011. I am grateful to the workshop’s audience and participants for their questions and comments. I am indebted to Eric Reuland and an anonymous reviewer for providing valuable feedback on the first draft, as well as to Yakov Testelets for numerous discussions of anaphora-related issues inAvar spanning several years. -

8. Binding Theory

THE COMPLICATED AND MURKY WORLD OF BINDING THEORY We’re about to get sucked into a black hole … 11-13 March Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 2 OUR ROADMAP •Overview of Basic Binding Theory •Binding and Infinitives •Some cross-linguistic comparisons: Icelandic, Ewe, and Logophors •Picture NPs •Binding and Movement: The Nixon Sentences 3 SOME TERMINOLOGY • R-expression: A DP that gets its meaning by referring to an entity in the world. • Anaphor: A DP that obligatorily gets its meaning from another DP in the sentence. 1. Heidi bopped herself on the head with a zucchini. [Carnie 2013: Ch. 5, EX 3] • Reflexives: Myself, Yourself, Herself, Himself, Itself, Ourselves, Yourselves, Themselves • Reciprocals: Each Other, One Another • Pronoun: A DP that may get its meaning from another DP in the sentence or contextually, from the discourse. 2. Art said that he played basketball. [EX5] • “He” could be Art or someone else. • I/Me, You/You, She/Her, He/Him, It/It, We/Us, You/You, They/Them • Nominative/Accusative Pronoun Pairs in English • Antecedent: A DP that gives its meaning to another DP. • This is familiar from control; PRO needs an antecedent. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 4 OBSERVATION 1: NO NOMINATIVE FORMS OF ANAPHORS • This makes sense, since anaphors cannot be subjects of finite clauses. 1. * Sheselfi / Herselfi bopped Heidii on the head with a zucchini. • Anaphors can be the subjects of ECM clauses. 2. Heidi believes herself to be an excellent cook, even though she always bops herself on the head with zucchini. SOME DESCRIPTIVE OBSERVATIONS Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. -

Pronouns, Logical Variables, and Logophoricity in Abe Author(S): Hilda Koopman and Dominique Sportiche Source: Linguistic Inquiry, Vol

MIT Press Pronouns, Logical Variables, and Logophoricity in Abe Author(s): Hilda Koopman and Dominique Sportiche Source: Linguistic Inquiry, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Autumn, 1989), pp. 555-588 Published by: MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4178645 Accessed: 22-10-2015 18:32 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Linguistic Inquiry. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.97.27.20 on Thu, 22 Oct 2015 18:32:27 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Hilda Koopman Pronouns, Logical Variables, Dominique Sportiche and Logophoricity in Abe 1. Introduction 1.1. Preliminaries In this article we describe and analyze the propertiesof the pronominalsystem of Abe, a Kwa language spoken in the Ivory Coast, which we view as part of the study of pronominalentities (that is, of possible pronominaltypes) and of pronominalsystems (that is, of the cooccurrence restrictionson pronominaltypes in a particulargrammar). Abe has two series of thirdperson pronouns. One type of pronoun(0-pronoun) has basically the same propertiesas pronouns in languageslike English. The other type of pronoun(n-pronoun) very roughly corresponds to what has been called the referential use of pronounsin English(see Evans (1980)).It is also used as what is called a logophoric pronoun-that is, a particularpronoun that occurs in special embedded contexts (the logophoric contexts) to indicate reference to "the person whose speech, thought or perceptions are reported" (Clements (1975)). -

Chapter 6 Mirativity and the Bulgarian Evidential System Elena Karagjosova Freie Universität Berlin

Chapter 6 Mirativity and the Bulgarian evidential system Elena Karagjosova Freie Universität Berlin This paper provides an account of the Bulgarian admirative construction andits place within the Bulgarian evidential system based on (i) new observations on the morphological, temporal, and evidential properties of the admirative, (ii) a criti- cal reexamination of existing approaches to the Bulgarian evidential system, and (iii) insights from a similar mirative construction in Spanish. I argue in particular that admirative sentences are assertions based on evidence of some sort (reporta- tive, inferential, or direct) which are contrasted against the set of beliefs held by the speaker up to the point of receiving the evidence; the speaker’s past beliefs entail a proposition that clashes with the assertion, triggering belief revision and resulting in a sense of surprise. I suggest an analysis of the admirative in terms of a mirative operator that captures the evidential, temporal, aspectual, and modal properties of the construction in a compositional fashion. The analysis suggests that although mirativity and evidentiality can be seen as separate semantic cate- gories, the Bulgarian admirative represents a cross-linguistically relevant case of a mirative extension of evidential verbal forms. Keywords: mirativity, evidentiality, fake past 1 Introduction The Bulgarian evidential system is an ongoing topic of discussion both withre- spect to its interpretation and its morphological buildup. In this paper, I focus on the currently poorly understood admirative construction. The analysis I present is based on largely unacknowledged observations and data involving the mor- phological structure, the syntactic environment, and the evidential meaning of the admirative. Elena Karagjosova. -

Participant-Internal Possibility Modality and It's

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 6 No 5 S2 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy September 2015 Participant-internal Possibility Modality and It’s Coding by – A Bil Analytical Construction in Kazakh Gulzada Salmyrzakyzy Yeshniyaz Botagoz Ermekovna Tassyrova Dauren Bakhytzhanovich Boranbayev Kazakh Ablai Khan University of international relations and world languages, The Republic of Kazakhstan 050022, Almaty, Muratbaev Street, 200 Ruslan Askarbekovich Yermagambetov The Korkyt Ata Kyzylorda State University, The Republic of Kazakhstan, 120014, Kyzylorda, Aiteke Bie Street, 29A Doi:10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n5s2p211 Abstract This paper discusses the semantic paradigm of the participant-internal possibility modality as a subcategory of modality and it’s coding in Kazakh with –A bil analytical construction. We will show that –A bil expresses all semantic properties of participant- internal possibility modality such as inherent/ learnt and mental/physical. Therefore constitutes the core of the functional- semantic field of the given modality. The paper also accounts for the relation of –A bil in modal usage with other category operators such as aspect, tense and voice. Keywords: modality, ability, participant-internal, converb, functional approach 1. Introduction Despite the available vast literature on modality there is still does not exist the single definition of the domain of modality in linguistics. Mostly modality is understood as a united meaning of its subcategories which are still under scrutiny and new concepts are being offered which make difficult to stabilize the semantics of modality. It is not once noted that “the number of modalities one decide upon is to some extent a matter of different ways of slicing the same cake” (Perkins, 1983, p.10). -

Why Grammar Matters: Conjugating Verbs in Modern Legal Opinions Robert C

Loyola University Chicago Law Journal Volume 40 Article 3 Issue 1 Fall 2008 2008 Why Grammar Matters: Conjugating Verbs in Modern Legal Opinions Robert C. Farrell Quinnipiac University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert C. Farrell, Why Grammar Matters: Conjugating Verbs in Modern Legal Opinions, 40 Loy. U. Chi. L. J. 1 (2008). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj/vol40/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago Law Journal by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Why Grammar Matters: Conjugating Verbs in Modern Legal Opinions Robert C. Farrell* I. INTRODUCTION Does it matter that the editors of thirty-three law journals, including those at Yale and Michigan, think that there is a "passive tense"? l Does it matter that the United States Courts of Appeals for the Sixth2 and Eleventh3 Circuits think that there is a "passive mood"? Does it matter that the editors of fourteen law reviews think that there is a "subjunctive tense"?4 Does it matter that the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit thinks that there is a "subjunctive voice'"? 5 There is, in fact, no "passive tense" or "passive mood." The passive is a voice. 6 There is no "subjunctive voice" or "subjunctive tense." The subjunctive is a mood.7 The examples in the first paragraph suggest that there is widespread unfamiliarity among lawyers and law students * B.A., Trinity College; J.D., Harvard University; Professor, Quinnipiac University School of Law. -

A Syntactic Analysis of Rhetorical Questions

A Syntactic Analysis of Rhetorical Questions Asier Alcázar 1. Introduction* A rhetorical question (RQ: 1b) is viewed as a pragmatic reading of a genuine question (GQ: 1a). (1) a. Who helped John? [Mary, Peter, his mother, his brother, a neighbor, the police…] b. Who helped John? [Speaker follows up: “Well, me, of course…who else?”] Rohde (2006) and Caponigro & Sprouse (2007) view RQs as interrogatives biased in their answer set (1a = unbiased interrogative; 1b = biased interrogative). In unbiased interrogatives, the probability distribution of the answers is even.1 The answer in RQs is biased because it belongs in the Common Ground (CG, Stalnaker 1978), a set of mutual or common beliefs shared by speaker and addressee. The difference between RQs and GQs is thus pragmatic. Let us refer to these approaches as Option A. Sadock (1971, 1974) and Han (2002), by contrast, analyze RQs as no longer interrogative, but rather as assertions of opposite polarity (2a = 2b). Accordingly, RQs are not defined in terms of the properties of their answer set. The CG is not invoked. Let us call these analyses Option B. (2) a. Speaker says: “I did not lie.” b. Speaker says: “Did I lie?” [Speaker follows up: “No! I didn’t!”] For Han (2002: 222) RQs point to a pragmatic interface: “The representation at this level is not LF, which is the output of syntax, but more abstract than that. It is the output of further post-LF derivation via interaction with at least a sub part of the interpretational component, namely pragmatics.” RQs are not seen as syntactic objects, but rather as a post-syntactic interface phenomenon. -

Tagalog Pala: an Unsurprising Case of Mirativity

Tagalog pala: an unsurprising case of mirativity Scott AnderBois Brown University Similar to many descriptions of miratives cross-linguistically, Schachter & Otanes(1972)’s clas- sic descriptive grammar of Tagalog describes the second position particle pala as “expressing mild surprise at new information, or an unexpected event or situation.” Drawing on recent work on mi- rativity in other languages, however, we show that this characterization needs to be refined in two ways. First, we show that while pala can be used in cases of surprise, pala itself merely encodes the speaker’s sudden revelation with the counterexpectational nature of surprise arising pragmatically or from other aspects of the sentence such as other particles and focus. Second, we present data from imperatives and interrogatives, arguing that this revelation need not concern ‘information’ per se, but rather the illocutionay update the sentence encodes. Finally, we explore the interactions between pala and other elements which express mirativity in some way and/or interact with the mirativity pala expresses. 1. Introduction Like many languages of the Philippines, Tagalog has a prominent set of discourse particles which express a variety of different evidential, attitudinal, illocutionary, and discourse-related meanings. Morphosyntactically, these particles have long been known to be second-position clitics, with a number of authors having explored fine-grained details of their distribution, rela- tive order, and the interaction of this with different types of sentences (e.g. Schachter & Otanes (1972), Billings & Konopasky(2003) Anderson(2005), Billings(2005) Kaufman(2010)). With a few recent exceptions, however, comparatively little has been said about the semantics/prag- matics of these different elements beyond Schachter & Otanes(1972)’s pioneering work (which is quite detailed given their broad scope of their work).