Ryokoakamaexploringemptines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1785-1998 September 1998

THE EVOLUTION OF THE BROADWOOD GRAND PIANO 1785-1998 by Alastair Laurence DPhil. University of York Department of Music September 1998 Broadwood Grand Piano of 1801 (Finchcocks Collection, Goudhurst, Kent) Abstract: The Evolution of the Broadwood Grand Piano, 1785-1998 This dissertation describes the way in which one company's product - the grand piano - evolved over a period of two hundred and thirteen years. The account begins by tracing the origins of the English grand, then proceeds with a description of the earliest surviving models by Broadwood, dating from the late eighteenth century. Next follows an examination of John Broadwood and Sons' piano production methods in London during the early nineteenth century, and the transition from small-scale workshop to large factory is noted. The dissertation then proceeds to record in detail the many small changes to grand design which took place as the nineteenth century progressed, ranging from the extension of the keyboard compass, to the introduction of novel technical features such as the famous Broadwood barless steel frame. The dissertation concludes by charting the survival of the Broadwood grand piano since 1914, and records the numerous difficulties which have faced the long-established company during the present century. The unique feature of this dissertation is the way in which much of the information it contains has been collected as a result of the writer's own practical involvement in piano making, tuning and restoring over a period of thirty years; he has had the opportunity to examine many different kinds of Broadwood grand from a variety of historical periods. -

Annual Report 2018–2019 Artmuseum.Princeton.Edu

Image Credits Kristina Giasi 3, 13–15, 20, 23–26, 28, 31–38, 40, 45, 48–50, 77–81, 83–86, 88, 90–95, 97, 99 Emile Askey Cover, 1, 2, 5–8, 39, 41, 42, 44, 60, 62, 63, 65–67, 72 Lauren Larsen 11, 16, 22 Alan Huo 17 Ans Narwaz 18, 19, 89 Intersection 21 Greg Heins 29 Jeffrey Evans4, 10, 43, 47, 51 (detail), 53–57, 59, 61, 69, 73, 75 Ralph Koch 52 Christopher Gardner 58 James Prinz Photography 76 Cara Bramson 82, 87 Laura Pedrick 96, 98 Bruce M. White 74 Martin Senn 71 2 Keith Haring, American, 1958–1990. Dog, 1983. Enamel paint on incised wood. The Schorr Family Collection / © The Keith Haring Foundation 4 Frank Stella, American, born 1936. Had Gadya: Front Cover, 1984. Hand-coloring and hand-cut collage with lithograph, linocut, and screenprint. Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960 / © 2017 Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 12 Paul Wyse, Canadian, born United States, born 1970, after a photograph by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, American, born 1952. Toni Morrison (aka Chloe Anthony Wofford), 2017. Oil on canvas. Princeton University / © Paul Wyse 43 Sally Mann, American, born 1951. Under Blueberry Hill, 1991. Gelatin silver print. Museum purchase, Philip F. Maritz, Class of 1983, Photography Acquisitions Fund 2016-46 / © Sally Mann, Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery © Helen Frankenthaler Foundation 9, 46, 68, 70 © Taiye Idahor 47 © Titus Kaphar 58 © The Estate of Diane Arbus LLC 59 © Jeff Whetstone 61 © Vesna Pavlovic´ 62 © David Hockney 64 © The Henry Moore Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 65 © Mary Lee Bendolph / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York 67 © Susan Point 69 © 1973 Charles White Archive 71 © Zilia Sánchez 73 The paper is Opus 100 lb. -

Ellen Fullman

A Compositional Approach Derived from Material and Ephemeral Elements Ellen Fullman My primary artistic activity has been focused coffee cans with large metal mix- around my installation the Long String Instrument, in which ing bowls filled with water and rosin-coated fingers brush across dozens of metallic strings, rubbed the wires with my hands, ABSTRACT producing a chorus of minimal, organ-like overtones, which tipping the bowl to modulate the The author discusses her has been compared to the experience of standing inside an sound. I wanted to be able to tune experiences in conceiving, enormous grand piano [1]. the wire, but changing the tension designing and working with did nothing. I knew I needed help the Long String Instrument, from an engineer. At the time I was an ongoing hybrid of installa- BACKGROUND tion and instrument integrat- listening with great interest to Pau- ing acoustics, engineering In 1979, during my senior year studying sculpture at the Kan- line Oliveros’s album Accordion and and composition. sas City Art Institute, I became interested in working with Voice. I could imagine making mu- sound in a concrete way using tape-recording techniques. This sic with this kind of timbre, playing work functioned as soundtracks for my performance art. I also created a metal skirt sound sculpture, a costume that I wore in which guitar strings attached to the toes and heels of my Fig. 1. Metal Skirt Sound Sculpture, 1980. (© Ellen Fullman. Photo © Ann Marsden.) platform shoes and to the edges of the “skirt” automatically produced rising and falling glissandi as they were stretched and released as I walked (Fig. -

Andrew Nolan Viennese

Restoration report South German or Austrian Tafelklavier c. 1830-40 Andrew Nolan, Broadbeach, Queensland. copyright 2011 Description This instrument is a 6 1/2 octave (CC-g4) square piano of moderate size standing on 4 reeded conical legs with casters, veneered in bookmatched figured walnut in Biedermeier furniture style with a single line of inlaid stringing at the bottom of the sides and a border around the top of the lid. This was originally stained red to resemble mahogany and the original finish appearance is visible under the front lid flap. The interior is veneered in bookmatched figured maple with a line of dark stringing. It has a wrought iron string plate on the right which is lacquered black on a gold base with droplet like pattern similar to in concept to the string plates of Broadwood c 1828-30. The pinblock and yoke are at the front of the instrument over the keyboard as in a grand style piano and the bass strings run from the front left corner to the right rear corner. The stringing is bichord except for the extreme bass CC- C where there are single overwound strings, and the top 1 1/2 octaves of the treble where there is trichord stringing. The top section of the nut for the trichords is made of an iron bar with brass hitch pins inserted at the top, this was screwed and glued to the leading edge of the pinblock. There is a music rack of walnut which fits into holes in the yoke. The back of this rack is hinged in the middle and at the bottom. -

Piano Manufacturing an Art and a Craft

Nikolaus W. Schimmel Piano Manufacturing An Art and a Craft Gesa Lücker (Concert pianist and professor of piano, University for Music and Drama, Hannover) Nikolaus W. Schimmel Piano Manufacturing An Art and a Craft Since time immemorial, music has accompanied mankind. The earliest instrumentological finds date back 50,000 years. The first known musical instrument with fibers under ten sion serving as strings and a resonator is the stick zither. From this small beginning, a vast array of plucked and struck stringed instruments evolved, eventually resulting in the first stringed keyboard instruments. With the invention of the hammer harpsichord (gravi cembalo col piano e forte, “harpsichord with piano and forte”, i.e. with the capability of dynamic modulation) in Italy by Bartolomeo Cristofori toward the beginning of the eighteenth century, the pianoforte was born, which over the following centuries evolved into the most versitile and widely disseminated musical instrument of all time. This was possible only in the context of the high level of devel- opment of artistry and craftsmanship worldwide, particu- larly in the German-speaking part of Europe. Since 1885, the Schimmel family has belonged to a circle of German manufacturers preserving the traditional art and craft of piano building, advancing it to ever greater perfection. Today Schimmel ranks first among the resident German piano manufacturers still owned and operated by Contents the original founding family, now in its fourth generation. Schimmel pianos enjoy an excellent reputation worldwide. 09 The Fascination of the Piano This booklet, now in its completely revised and 15 The Evolution of the Piano up dated eighth edition, was first published in 1985 on The Origin of Music and Stringed Instruments the occa sion of the centennial of Wilhelm Schimmel, 18 Early Stringed Instruments – Plucked Wood Pianofortefa brik GmbH. -

Hiver 2017 Éditorial

HIVER 2017 ÉDITORIAL DE RETOUR DES TRANS Dimanche 4 décembre à 10h57, je me pose dans le train qui me ramène de Rennes avec ma valise à roulettes bruyantes dans une main et un grand café fumant dans l’autre, les yeux encore mi-clos mais des sons et des images pleins la tête. La 38ème édition des Transmusicales de Rennes fut ma 5ème d’affilée. Je regarde les paysages défiler à la vitesse du Train à Grande Vitesse en songeant aux quelques soixante groupes que j’ai dû voir en quatre jours, remontant sur mon petit carnet le nom des groupes appréciés ou qui m’ont déçus lors du festival, potentiellement programmables ou pas à la Cave aux Poètes. Je me pose alors une question essentielle, voire existentialiste : est-ce que je vais vraiment aux Transmusicales pour programmer les groupes dans la foulée sous le prétexte qu’ils ont tous des agents en France déjà au travail sur leur imminente tournée française ? Et là je me dis, en retraçant les cinq éditions écoulées à vitesse grand V, que finalement je vais un peu aux Transmusicales de Rennes comme les gens de la mode vont au Salon « Première vision » : on y découvre les tendances de demain, et pas seulement des groupes en particulier. Alors j’examine la programmation, lis quelques premiers articles, et tente de me remémorer certaines conversations avec d’éminents confrères programmateurs… Et pour parler de tendances, il y alors trois idées majeures qui me viennent à l’esprit pour les années à venir. La première est qu’une large place est donnée cette année aux musiques du monde, comme une sorte de barrage aux élans nationalistes actuels ou comme une capacité d’ouverture de la jeunesse qui prend aujourd’hui l’avion comme on prend le métro. -

Voices of the Electric Guitar

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 2012 Voices of the electric guitar Don Curnow California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes Recommended Citation Curnow, Don, "Voices of the electric guitar" (2012). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 369. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes/369 This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. Unless otherwise indicated, this project was conducted as practicum not subject to IRB review but conducted in keeping with applicable regulatory guidance for training purposes. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Voices of the Electric Guitar Don Curnow MPA 475 12-12-12 Intro The solid body electric guitar is the result of many guitars and innovations that came before it, followed by the guitar's need for volume to compete with louder instruments, particularly when soloing. In the 1930s, jazz and its various forms incorporated the guitar, but at the time there was no way for an acoustic guitar to compete with the volume of a trumpet or saxophone, let alone with an orchestra of trumpets and saxophones, such as in big band jazz. As a result, amplification of the guitar was born and the electric guitar has been evolving since, from a hollow bodied ES-150 arch-top with a pick-up used by Charlie Christian to the Les Paul played by Slash today. -

Transitions Spring 2014 # from the Archives … Fall of 2016 Marked the 50Th Anniversary of Prescott College Opening Its Doors

TransitionS Celebrating 50 Years of Innovation Transitions Spring 2014 # From the Archives … Fall of 2016 marked the 50th anniversary of Prescott College opening its doors. We’ve been taking time to look back, and reflect on the winding journey that has led us to where we stand today. Transitions has played an important role in keeping our friends and alumni connected to campus. Enjoy the selection of historic covers! From Last Issue: We didn’t hear from anyone about this image! If you know the who, what or when about these animated performers, let us know at [email protected]. Photos courtesy of the College Archives Prescott Connect with us There are more ways than ever to tell us what’s on your mind: Call us. We’d love to hear your feedback Email us at (928) 350-4506 [email protected] Transitions Magazine Twitter users can follow Join our Facebook Prescott College Prescott College at community. Log on to 220 Grove Ave. twitter.com/PrescottCollege facebook.com/PrescottCollege Prescott, AZ 86301 Cover photo: 50th Anniversary mural by the Spring 2017 Public Art: Mural Painting class Contents TransitionS 8 Alumni Bike Cuba with Former Faculty Publisher and Editor 12 Charles Franklin Parker’s Rose Window Ashley Hust 14 Prescott College Ratings and Rankings Designer Miriam Glade 15 Rock Climbing Board of Trustees Contributing Writers 16 Student Wins EPA Fellowship Michael Belef • Scott Bennett • Sue Bray • Paul Burkhardt June Burnside Tackett • Susan DeFreitas • Liz Faller 17 Prescott College Innovations in Higher Ed Elizabeth Fawley • John Flicker • Ashley Hust • Maria Johnson • Leslie Laird • Nelson Lee • David Mazurkiewicz 18 50th Anniversary Celebration Robert Miller • Jorge Miros • Amanda Pekar • Mark Riegner • Micah Riegner • Elisabeth Ruffner • Kayla Sargent • Peter Sherman, • Marie Smith • Wyatt Smith 22 Kino Fellows: Where Are They Now? Astrea Strawn • David White • Gratia Winship • Lisa Zander 24 Leslie Laird Reflects On Path to PC Staff Photographers Shayna Beasley • Miriam Glade • Ashley Hust 26 Ronald C. -

St.-Thomas-Aquinas-The-Summa-Contra-Gentiles.Pdf

The Catholic Primer’s Reference Series: OF GOD AND HIS CREATURES An Annotated Translation (With some Abridgement) of the SUMMA CONTRA GENTILES Of ST. THOMAS AQUINAS By JOSEPH RICKABY, S.J., Caution regarding printing: This document is over 721 pages in length, depending upon individual printer settings. The Catholic Primer Copyright Notice The contents of Of God and His Creatures: An Annotated Translation of The Summa Contra Gentiles of St Thomas Aquinas is in the public domain. However, this electronic version is copyrighted. © The Catholic Primer, 2005. All Rights Reserved. This electronic version may be distributed free of charge provided that the contents are not altered and this copyright notice is included with the distributed copy, provided that the following conditions are adhered to. This electronic document may not be offered in connection with any other document, product, promotion or other item that is sold, exchange for compensation of any type or manner, or used as a gift for contributions, including charitable contributions without the express consent of The Catholic Primer. Notwithstanding the preceding, if this product is transferred on CD-ROM, DVD, or other similar storage media, the transferor may charge for the cost of the media, reasonable shipping expenses, and may request, but not demand, an additional donation not to exceed US$25. Questions concerning this limited license should be directed to [email protected] . This document may not be distributed in print form without the prior consent of The Catholic Primer. Adobe®, Acrobat®, and Acrobat® Reader® are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated in the United States and/or other countries. -

A Performer's Guide to the Prepared Piano of John Cage

A Performer’s Guide to the Prepared Piano of John Cage: The 1930s to 1950s. A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Keyboard Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music By Sejeong Jeong B.M., Sookmyung Women’s University, 2011 M.M., Illinois State University, 2014 ________________________________ Committee Chair : Jeongwon Joe, Ph. D. ________________________________ Reader : Awadagin K.A. Pratt ________________________________ Reader : Christopher Segall, Ph. D. ABSTRACT John Cage is one of the most prominent American avant-garde composers of the twentieth century. As the first true pioneer of the “prepared piano,” Cage’s works challenge pianists with unconventional performance practices. In addition, his extended compositional techniques, such as chance operation and graphic notation, can be demanding for performers. The purpose of this study is to provide a performer’s guide for four prepared piano works from different points in the composer’s career: Bacchanale (1938), The Perilous Night (1944), 34'46.776" and 31'57.9864" For a Pianist (1954). This document will detail the concept of the prepared piano as defined by Cage and suggest an approach to these prepared piano works from the perspective of a performer. This document will examine Cage’s musical and philosophical influences from the 1930s to 1950s and identify the relationship between his own musical philosophy and prepared piano works. The study will also cover challenges and performance issues of prepared piano and will provide suggestions and solutions through performance interpretations. -

Nemeth Code Uses Some Parts of Textbook Format but Has Some Idiosyncrasies of Its Own

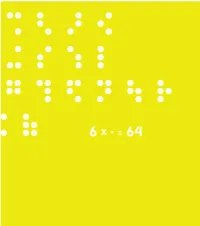

This book is a compilation of research, in “Understanding and Tracing the Problem faced by the Visually Impaired while doing Mathematics” as a Diploma project by Aarti Vashisht at the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore. 6 DOTS 64 COMBINATIONS A Braille character is formed out of a combination of six dots. Including the blank space, sixty four combinations are possible using one or more of these six dots. CONTENTS Introduction 2 About Braille 32 Mathematics for the Visually Impaired 120 Learning Mathematics 168 C o n c l u s i o n 172 P e o p l e a n d P l a c e s 190 Acknowledgements INTRODUCTION This project tries to understand the nature of the problems that are faced by the visually impaired within the realm of mathematics. It is a summary of my understanding of the problems in this field that may be taken forward to guide those individuals who are concerned about this subject. My education in design has encouraged interest in this field. As a designer I have learnt to be aware of my community and its needs, to detect areas where design can reach out and assist, if not resolve, a problem. Thus began, my search, where I sought to grasp a fuller understanding of the situation by looking at the various mediums that would help better communication. During the project I realized that more often than not work happened in individual pockets which in turn would lead to regionalization of many ideas and opportunities. Data collection got repetitive, which would delay or sometimes even hinder the process. -

Points in Recent History

San Francisco Contemporary Music Players Performers: Points in Recent History Tod Brody, flute Monday, November 8, 2010, 8 pm Peter Josheff, clarinet Herbst Theatre Jacob Zimmerman, saxophone David Tanenbaum, guitar Michael Seth Orland, piano Dominique Leone, keyboard JÉRÔME COMBIER Regina Schaffer, keyboard Essere pietra (To Be Stone) (2004) Loren Mach, percussion (Combier) (Approximate duration: 6 minutes) William Winant, percussion (Cage, Glass) Susan Freier, violin Heurter la lumière encore (To Hit the Light Again) (2005) Nanci Severance, viola United States premiere Stephen Harrison, cello (Approximate duration: 5 minutes) 2 JOHN CAGE Robert Shumaker, Recording Engineer Seven (1988) San Francisco Contemporary Music Players Co-Commission 2 This project has been made possible by the National Endowment for the Arts as part of American Masterpieces: Three Centuries of Artistic Genius. (Approximate duration: 20 minutes) Tonight’s performance is supported in part by the National Endowment for the Arts and the Wells Fargo Foundation. Intermission Tonight’s performances of Heurter la lumière encore and Essere pietra are sup- ported in part by The French-American Fund for Contemporary Music, a program of FACE with support from Cultural Services of the French Embassy, CulturesFrance, SACEM and the Florence Gould Foundation. GABRIELE VANONI Space Oddities (2008) Tonight’s performance of music by Gabriele Vanoni is made possible in part West Coast premiere by the generaous support of the Istituto Italiano de Cultura. (Approximate duration: 8 minutes) Tod Brody, flute PHILIP GLASS Music in Similar Motion (1969) (Approximate duration: 15 minutes) Program Notes (b. 1947) best known for his nature-inspired sculptures and mixed- media work. Two other artists of Combier’s own generation also had JÉRÔME COMBIER (b.