Points in Recent History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neo-Modern Contemplative and Sublime Cinema Aesthetics in Godfrey Reggio’S Qatsi Trilogy

Art Inquiry. Recherches sur les arts 2016, vol. XVIII ISSN 1641-9278 / e - ISSN 2451-0327219 Kornelia Boczkowska Faculty of English Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań [email protected] SPEEDING SLOWNESS: NEO-MODERN CONTEMPLATIVE AND SUBLIME CINEMA AESTHETICS IN GODFREY REGGIO’S QATSI TRILOGY Abstract: The article analyzes the various ways in which Godfrey Reggio’s experimental documentary films, Koyaanisqatsi (1982), Powaqqatsi (1988) and Naqoyqatsi (2002), tend to incorporate narrative and visual conventions traditionally associated with neo-modern aesthetics of slow and sublime cinema. The former concept, defined as a “varied strain of austere minimalist cinema” (Romney 2010) and characterized by the frequent use of “long takes, de-centred and understated modes of storytelling, and a pronounced emphasis on quietude and the everyday” (Flanagan 2008), is often seen as a creative evolution of Schrader’s transcendental style or, more generally, neo-modernist trends in contemporary cinematography. Although predominantly analyzed through the lens of some common stylistic tropes of the genre’s mainstream works, its scope and framework has been recently broadened to encompass post-1960 experimental and avant-garde as well as realistic documentary films, which often emphasize contemplative rather than slow aspects of the projected scenes (Tuttle 2012). Taking this as a point of departure, I argue that the Qatsi trilogy, despite being classified as largely atypical slow films, relies on a set of conventions which draw both on the stylistic excess of non-verbal sublime cinema (Thompson 1977; Bagatavicius 2015) and on some formal devices of contemplative cinema, including slowness, duration, anti-narrative or Bazinian Realism. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2017). Michael Finnissy - The Piano Music (10 and 11) - Brochure from Conference 'Bright Futures, Dark Pasts'. This is the other version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17523/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] BRIGHT FUTURES, DARK PASTS Michael Finnissy at 70 Conference at City, University of London January 19th-20th 2017 Bright Futures, Dark Pasts Michael Finnissy at 70 After over twenty-five years sustained engagement with the music of Michael Finnissy, it is my great pleasure finally to be able to convene a conference on his work. This event should help to stimulate active dialogue between composers, performers and musicologists with an interest in Finnissy’s work, all from distinct perspectives. It is almost twenty years since the publication of Uncommon Ground: The Music of Michael Finnissy (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998). -

CALIFORNIA's NORTH COAST: a Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors

CALIFORNIA'S NORTH COAST: A Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors. A Geographically Arranged Bibliography focused on the Regional Small Presses and Local Authors of the North Coast of California. First Edition, 2010. John Sherlock Rare Books and Special Collections Librarian University of California, Davis. 1 Table of Contents I. NORTH COAST PRESSES. pp. 3 - 90 DEL NORTE COUNTY. CITIES: Crescent City. HUMBOLDT COUNTY. CITIES: Arcata, Bayside, Blue Lake, Carlotta, Cutten, Eureka, Fortuna, Garberville Hoopa, Hydesville, Korbel, McKinleyville, Miranda, Myers Flat., Orick, Petrolia, Redway, Trinidad, Whitethorn. TRINITY COUNTY CITIES: Junction City, Weaverville LAKE COUNTY CITIES: Clearlake, Clearlake Park, Cobb, Kelseyville, Lakeport, Lower Lake, Middleton, Upper Lake, Wilbur Springs MENDOCINO COUNTY CITIES: Albion, Boonville, Calpella, Caspar, Comptche, Covelo, Elk, Fort Bragg, Gualala, Little River, Mendocino, Navarro, Philo, Point Arena, Talmage, Ukiah, Westport, Willits SONOMA COUNTY. CITIES: Bodega Bay, Boyes Hot Springs, Cazadero, Cloverdale, Cotati, Forestville Geyserville, Glen Ellen, Graton, Guerneville, Healdsburg, Kenwood, Korbel, Monte Rio, Penngrove, Petaluma, Rohnert Part, Santa Rosa, Sebastopol, Sonoma Vineburg NAPA COUNTY CITIES: Angwin, Calistoga, Deer Park, Rutherford, St. Helena, Yountville MARIN COUNTY. CITIES: Belvedere, Bolinas, Corte Madera, Fairfax, Greenbrae, Inverness, Kentfield, Larkspur, Marin City, Mill Valley, Novato, Point Reyes, Point Reyes Station, Ross, San Anselmo, San Geronimo, San Quentin, San Rafael, Sausalito, Stinson Beach, Tiburon, Tomales, Woodacre II. NORTH COAST AUTHORS. pp. 91 - 120 -- Alphabetically Arranged 2 I. NORTH COAST PRESSES DEL NORTE COUNTY. CRESCENT CITY. ARTS-IN-CORRECTIONS PROGRAM (Crescent City). The Brief Pelican: Anthology of Prison Writing, 1993. 1992 Pelikanesis: Creative Writing Anthology, 1994. 1994 Virtual Pelican: anthology of writing by inmates from Pelican Bay State Prison. -

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Unstill Life: The Emergence and Evolution of Time-Lapse Photography Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2q89f608 Author Boman, James Stephan Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Unstill Life: The Emergence and Evolution of Time-Lapse Photography A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Studies by James Stephan Boman Committee in charge: Professor Janet Walker, Chair Professor Charles Wolfe Professor Peter Bloom Professor Colin Gardner September 2019 The dissertation of James Stephan Boman is approved. ___________________________________________________ Peter Bloom ___________________________________________________ Charles Wolfe ___________________________________________________ Colin Gardner ___________________________________________________ Janet Walker, Committee Chair March 2019 Unstill Life: The Emergence and Evolution of Time-Lapse Photography Copyright © 2019 By James Stephan Boman iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my friends and colleagues at UC Santa Barbara, including the fellow members of my cohort—Alex Champlin, Wesley Jacks, Jennifer Hessler, and Thong Winh—as well as Rachel Fabian, with whom I shared work during our prospectus seminar. I would also like to acknowledge the diverse and outstanding faculty members with whom I had the pleasure to work as a student at UCSB, including Lisa Parks, Michael Curtin, Greg Siegel, and the rest of the faculty. Anna Brusutti was also very important to my development as a teacher. Ross Melnick has been a source of unflagging encouragement and a fount of advice in my evolution within and beyond graduate school. -

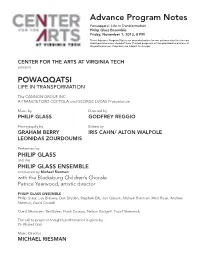

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. CENTER FOR THE ARTS AT VIRGINIA TECH presents POWAQQATSI LIFE IN TRANSFORMATION The CANNON GROUP INC. A FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA and GEORGE LUCAS Presentation Music by Directed by PHILIP GLASS GODFREY REGGIO Photography by Edited by GRAHAM BERRY IRIS CAHN/ ALTON WALPOLE LEONIDAS ZOURDOUMIS Performed by PHILIP GLASS and the PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE conducted by Michael Riesman with the Blacksburg Children’s Chorale Patrice Yearwood, artistic director PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE Philip Glass, Lisa Bielawa, Dan Dryden, Stephen Erb, Jon Gibson, Michael Riesman, Mick Rossi, Andrew Sterman, David Crowell Guest Musicians: Ted Baker, Frank Cassara, Nelson Padgett, Yousif Sheronick The call to prayer in tonight’s performance is given by Dr. Khaled Gad Music Director MICHAEL RIESMAN Sound Design by Kurt Munkacsi Film Executive Producers MENAHEM GOLAN and YORAM GLOBUS Film Produced by MEL LAWRENCE, GODFREY REGGIO and LAWRENCE TAUB Production Management POMEGRANATE ARTS Linda Brumbach, Producer POWAQQATSI runs approximately 102 minutes and will be performed without intermission. SUBJECT TO CHANGE PO-WAQ-QA-TSI (from the Hopi language, powaq sorcerer + qatsi life) n. an entity, a way of life, that consumes the life forces of other beings in order to further its own life. POWAQQATSI is the second part of the Godfrey Reggio/Philip Glass QATSI TRILOGY. With a more global view than KOYAANISQATSI, Reggio and Glass’ first collaboration, POWAQQATSI, examines life on our planet, focusing on the negative transformation of land-based, human- scale societies into technologically driven, urban clones. -

Ryokoakamaexploringemptines

University of Huddersfield Repository Akama, Ryoko Exploring Empitness: An Investigation of MA and MU in My Sonic Composition Practice Original Citation Akama, Ryoko (2015) Exploring Empitness: An Investigation of MA and MU in My Sonic Composition Practice. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/26619/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ EXPLORING EMPTINESS AN INVESTIGATION OF MA AND MU IN MY SONIC COMPOSITION PRACTICE Ryoko Akama A commentary accompanying the publication portfolio submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ! The University of Huddersfield School of Music, Humanities and Media April, 2015 Title: Exploring Emptiness Subtitle: An investigation of ma and mu in my sonic composition practice Name of student: Ryoko Akama Supervisor: Prof. -

The Postmodern Aspects Reflected in the Qatsi Trilogy

THE POSTMODERN ASPECTS REFLECTED IN THE QATSI TRILOGY by PETER-WAYNE VIVIER Submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree MAGISTER TECHNOLOGIAE: FINE ARTS in the Department of Fine & Applied Arts FACULTY OF THE ARTS TSHWANE UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Supervisor: Prof I Stevens Co-supervisor: Ms R Kruger Table of contents Chapter 1: Introduction................................................................................................. 3 1.1 Postmodernism.................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Godfrey Reggio and the Qatsi trilogy................................................................. 7 1.3 Research aims ..................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Research methods ............................................................................................... 9 1.5 Summary of chapters ........................................................................................ 10 Chapter 2: Postmodernism.......................................................................................... 11 2.1 Etymology......................................................................................................... 11 2.2 Definition.......................................................................................................... 13 2.3 From grand narratives to pluralism................................................................... 18 2.4 Production of meaning and reality................................................................... -

EINSTEIN on the BEACH BROOKLYN ACADEMY of MUSIC Harvey Lichtenstein, President and Executive Producer

EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC Harvey Lichtenstein, President and Executive Producer presents in the BAM Opera House November 19-23; 1992; 7PM EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH An Opera in Four Acts by Philip Glass Robert Wilson Choreography by Lucinda Childs with Lucinda Childs Sheryl Sutton Gregory Fulkerson Lighting Design Musical Direction Sound Design Beverly Emmons/Robert Wilson Michael Riesman Kurt Munkacsi Spoken Text Christopher Knowles/Samuel M. Johnson/Lucinda Childs with The Lucinda Childs Dance Company Music Performed by the I I Philip Glass Ensemble Design/Direction Music/Lyrics Robert Wilson Philip Glass Producer Jedediah Wheeler Einstein on the Beach is a production of Top Shows, Inc. These performances of Einstein on the Beach are dedicated to the memory of Eric Benson, Ethyl Eichelberger, Michel Guy, Samuel M. Johnson and Robert LoBianco, who were an important part of this work. This presentation has been made possible, in part, by grants from Robert W. Wilson, The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, The Bohen Foundation, and The Mary Flagler Cary Charitable Trust. THE COMPANY (in alphabetical' order) Marion Beckenstein soprano, rear stenographer (trial/prison) soloist (train, dance 1, night train, dance 2) Lisa Bielawa soprano, front stenographer (trial/prison), soloist (train, dance 1, night train, dance 2) Susan Blankensop* dancer, woman in perpendicular dance (train) Janet Charleston* dan€er, woman reading,itrial, building), prisoner 2 (trial, prison) Lucinda Childs featured dancer/performer, character -

MUSICAL and DRAMATIC FUNCTIONS of LOOPS and LOOP BREAKERS in PHILIP GLASS's OPERA the VOYAGE Chia-Ying Wu Dissertation Prepar

MUSICAL AND DRAMATIC FUNCTIONS OF LOOPS AND LOOP BREAKERS IN PHILIP GLASS’S OPERA THE VOYAGE Chia-Ying Wu Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2016 APPROVED: David Bard-Schwarz, Major Professor Hendrik Schulze, Related Field Professor Stephen Slottow, Committee Member Frank Heidlberger, Chair of the Division of Music History, Theory, and Ethnomusicology Warren Henry, Interim Dean of the College of Music Costas Tsatsoulis, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Copyright 2016 by Chia-Ying Wu ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Continuous support from faculty members and students of Music History, Theory and Musicology Division at the University of North Texas, and my family make the production of this dissertation possible. I wish to express my deepest appreciation to my major professor, Dr. David Schwarz, for guiding me through doctoral coursework, qualifying exams, dissertation proposal, and this dissertation; and also to my related field professor, Dr. Hendrik Schulze, who provides me insights into the field of opera. I appreciate the help from dissertation committee member Dr. Stephen Slottow for shaping this research from an idea to a dissertation; and also the help from Dr. Margaret Notley for the early development of this dissertation. I thank Jay Smith, a PhD student in music theory, for sharing his paper presented at the 2015 Texas Society for Music Theory conference. Finally, I would like to give special thanks to my father professor Chung-Yu (Peter) Wu at the National Chiao-Tung University in Taiwan, my mother Chao-Ling Wu Tseng, my younger sister Ying-Hsuen Wu, and relatives for their encouragement. -

John Conklin • Speight Jenkins • Risë Stevens • Robert Ward John Conklin John Conklin Speight Jenkins Speight Jenkins Risë Stevens Risë Stevens

2011 NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS 1100 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20506-0001 John Conklin • Speight Jenkins • Risë Stevens • Robert Ward John Conklin John Conklin Speight Jenkins Speight Jenkins Risë Stevens Risë Stevens Robert Ward Robert Ward NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS 2011 John Conklin’s set design sketch for San Francisco Opera’s production of The Ring Cycle. Image courtesy of John Conklin ii 2011 NEA OPERA HONORS Contents 1 Welcome from the NEA Chairman 2 Greetings from NEA Director of Music and Opera 3 Greetings from OPERA America President/CEO 4 Opera in America by Patrick J. Smith 2011 NEA OPERA HONORS RECIPIENTS 12 John Conklin Scenic and Costume Designer 16 Speight Jenkins General Director 20 Risë Stevens Mezzo-soprano 24 Robert Ward Composer PREVIOUS NEA OPERA HONORS RECIPIENTS 2010 30 Martina Arroyo Soprano 32 David DiChiera General Director 34 Philip Glass Composer 36 Eve Queler Music Director 2009 38 John Adams Composer 40 Frank Corsaro Stage Director/Librettist 42 Marilyn Horne Mezzo-soprano 44 Lotfi Mansouri General Director 46 Julius Rudel Conductor 2008 48 Carlisle Floyd Composer/Librettist 50 Richard Gaddes General Director 52 James Levine Music Director/Conductor 54 Leontyne Price Soprano 56 NEA Support of Opera 59 Acknowledgments 60 Credits 2011 NEA OPERA HONORS iii iv 2011 NEA OPERA HONORS Welcome from the NEA Chairman ot long ago, opera was considered American opera exists thanks in no to reside within an ivory tower, the small part to this year’s honorees, each of mainstay of those with European whom has made the art form accessible to N tastes and a sizable bankroll. -

PUCCINI International Opera Composition Course Summer

Summer Seminar 2020 July 6 th to 18 th - Lucca, Italy Come and study how to write opera in Lucca, the city of Giacomo Puccini Cluster – Compositori interpreti del presente in collaboration with: Fondazione Giacomo Puccini Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Lucca Fondazione Banca del Monte di Lucca Teatro del Giglio di Lucca EMA Vinci Produzioni discografiche (audio-video), editoriali ed artistiche. Present PUCCINI International Opera Composition Course Summer Seminar 2020 July 6 th to 18 th - Lucca, Italy Come and study how to write opera in Lucca, the city of Giacomo Puccini PROJECT The PUCCINI International Opera Composition Course is addressed to composers (both with or without an academic degree) willing to investigate thoroughly all compositional techniques in use in opera writing today, focusing both on the Italian tradition and on the genre’s contemporary international developments. The course’s aim is to hand down the great opera tradition, having as a target the creation of new operas, bridging the past and the future in a new and enthralling vision. COURSE GOALS Participants will get to a deeper understanding of the various aspects of composing for opera theatre. - At the end of the course, each participant must submit a complete pre-project for a new chamber opera, writing a section or a full score for voice and piano (at least 25 minutes) - The best projects will be selected to be performed as mise-en-scene at the ‘PUCCINI Chamber Opera Festival 2021’ in collaboration with Teatro del Giglio of Lucca - All scores produced will be published and recorded video/audio by EMA Vinci APPLICANTS SELECTION Applicants must submit the following materials for selection: - CV - Project scheme of a chamber opera for max 1 voice and piano - Full score and audio file of an orchestral or chamber composition* - Full score or voice/piano score and audio file of a vocal composition* *midi files can be accepted All materials must be e-mailed to [email protected] Submission deadline April, 30th 2020 Eligible composers will be contacted by May, 15th 2020. -

Philip Glass

DEBARTOLO PERFORMING ARTS CENTER PRESENTING SERIES PRESENTS MUSIC BY PHILIP GLASS IN A PERFORMANCE OF AN EVENING OF CHAMBER MUSIC WITH PHILIP GLASS TIM FAIN AND THIRD COAST PERCUSSION MARCH 30, 2019 AT 7:30 P.M. LEIGHTON CONCERT HALL Made possible by the Teddy Ebersol Endowment for Excellence in the Performing Arts and the Gaye A. and Steven C. Francis Endowment for Excellence in Creativity. PROGRAM: (subject to change) PART I Etudes 1 & 2 (1994) Composed and Performed by Philip Glass π There were a number of special events and commissions that facilitated the composition of The Etudes by Philip Glass. The original set of six was composed for Dennis Russell Davies on the occasion of his 50th birthday in 1994. Chaconnes I & II from Partita for Solo Violin (2011) Composed by Philip Glass Performed by Tim Fain π I met Tim Fain during the tour of “The Book of Longing,” an evening based on the poetry of Leonard Cohen. In that work, all of the instrumentalists had solo parts. Shortly after that tour, Tim asked me to compose some solo violin music for him. I quickly agreed. Having been very impressed by his ability and interpretation of my work, I decided on a seven-movement piece. I thought of it as a Partita, the name inspired by the solo clavier and solo violin music of Bach. The music of that time included dance-like movements, often a chaconne, which represented the compositional practice. What inspired me about these pieces was that they allowed the composer to present a variety of music composed within an overall structure.