Death and Afterlife in Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Inferiority Complex of Homunculus in Hiromu Arakawa's

The Inferiority Complex of Homunculus in Hiromu Arakawa’s Fullmetal Alchemist Thenady, T.P.1 and Limanta, L.S.2 1,2) English Department, Faculty of Letters, Petra Christian University, Siwalankerto 121-131, Surabaya 60236, East Java, INDONESIA e-mails: [email protected]; [email protected] ABSTRACT This article explores the causes and effects of inferiority complex in a character of a manga created by Hiromu Arakawa, Fullmetal Alchemist. Commonly seen as a child’s play and underestimated by the society of literature, comic book or manga actually has the same quality as those considered as literary arts and stands equally with them. It embraces issues freely without the restriction of social rules and individual or group and uncontaminated by social, personal, or political influences. One of the issues most people think will not be in a comic book is psychology. Started from comparing himself to humans, the main antagonist, Homunculus, suffers from an inferiority complex caused by several factors such as parental attitude, physical defects, and envy. Furthermore, as the effect of suffering inferiority complex, Homunculus develops psychological defenses to ease his inferiorities: compensation and superiority complex. He tries to compensate his inferior feelings by excelling in another area and covers up the inferiorities by striving for superiority and omnipotence. Keywords: Manga, Alchemist, Homunculus, Inferiority Complex, Compensation, Superiority Complex Hiromu Arakawa is a Hokkaido-born manga artist whose career began with Stray Dog in 1999. One of her most successful works is Fullmetal Alchemist. This manga had won numerous awards such as 49th Shogakukan Manga Award for shounen category, 15th Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize “New Artist” category, and 9th 21st Century Shounen Gangan Award (Shogakukan). -

The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2009 The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M. Stockins University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Stockins, Jennifer M., The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney, Master of Arts - Research thesis, University of Wollongong. School of Art and Design, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/3164 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Master of Arts - Research (MA-Res) UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG Jennifer M. Stockins, BCA (Hons) Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Art and Design 2009 ii Stockins Statement of Declaration I certify that this thesis has not been submitted for a degree to any other university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference has been made in the text. Jennifer M. Stockins iii Stockins Abstract Manga (Japanese comic books), Anime (Japanese animation) and Superflat (the contemporary art by movement created Takashi Murakami) all share a common ancestry in the woodblock prints of the Edo period, which were once mass-produced as a form of entertainment. -

11Eyes Achannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air

11eyes AChannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air Master Amaenaideyo Angel Beats Angelic Layer Another Ao No Exorcist Appleseed XIII Aquarion Arakawa Under The Bridge Argento Soma Asobi no Iku yo Astarotte no Omocha Asu no Yoichi Asura Cryin' B Gata H Kei Baka to Test Bakemonogatari (and sequels) Baki the Grappler Bakugan Bamboo Blade Banner of Stars Basquash BASToF Syndrome Battle Girls: Time Paradox Beelzebub BenTo Betterman Big O Binbougami ga Black Blood Brothers Black Cat Black Lagoon Blassreiter Blood Lad Blood+ Bludgeoning Angel Dokurochan Blue Drop Bobobo Boku wa Tomodachi Sukunai Brave 10 Btooom Burst Angel Busou Renkin Busou Shinki C3 Campione Cardfight Vanguard Casshern Sins Cat Girl Nuku Nuku Chaos;Head Chobits Chrome Shelled Regios Chuunibyou demo Koi ga Shitai Clannad Claymore Code Geass Cowboy Bebop Coyote Ragtime Show Cuticle Tantei Inaba DFrag Dakara Boku wa, H ga Dekinai Dan Doh Dance in the Vampire Bund Danganronpa Danshi Koukousei no Nichijou Daphne in the Brilliant Blue Darker Than Black Date A Live Deadman Wonderland DearS Death Note Dennou Coil Denpa Onna to Seishun Otoko Densetsu no Yuusha no Densetsu Desert Punk Detroit Metal City Devil May Cry Devil Survivor 2 Diabolik Lovers Disgaea Dna2 Dokkoida Dog Days Dororon EnmaKun Meeramera Ebiten Eden of the East Elemental Gelade Elfen Lied Eureka 7 Eureka 7 AO Excel Saga Eyeshield 21 Fight Ippatsu! JuudenChan Fooly Cooly Fruits Basket Full Metal Alchemist Full Metal Panic Futari Milky Holmes GaRei Zero Gatchaman Crowds Genshiken Getbackers Ghost -

Aniplex of America to Release the Complete First Season of Silver Spoon on DVD

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 24, 2014 Aniplex of America to Release The Complete First Season of Silver Spoon on DVD ©Hiromu Arakawa, Shogakukan/EZONO Festa Executive Committee From the Author of the Hit Series Fullmetal Alchemist Comes a Story of Farm work, Friendship, and the Freshest Food! SANTA MONICA, CA (May 24, 2014) –Aniplex of America announced earlier today of their plans to release the first season of Silver Spoon in a complete DVD set on July 15th. Pre-orders for this product will begin on May 27th through official Aniplex of America retailers. Silver Spoon is an anime adaptation of the manga series originally created by author, Hiromu Arakawa (Fullmetal Alchemist), which has been awarded both the 5th Manga Taisho Award and the 58th Shogakukan Manga Award in 2012. The unique story follows Yugo Hachiken, a young man who decides to attend an agricultural high school in the countryside of Hokkaido prefecture in order to escape the academic pressures he had to live within the city. The series demonstrates how Yugo, who is initially burned-out, comes to see his life through a different light as he engages with his classmates and works with the animals on the farm at Oezo Agricutral High School a.k.a. Ezono. The anime series is directed by Tomohiko Ito, best known for his work with Sword Art Online, and the animation was produced by A-1 Pictures notable for their work on popular titles such as Sword Art Online, Magi: The Kingdom of Magic, Blue Exorcist, and Oreimo 2. The first season of Silver Spoon’s anime series began its simulcast schedule in July of last year. -

Anime Episode Release Dates

Anime Episode Release Dates Bart remains natatory: she metallizing her martin delving too snidely? Is Ingemar always unadmonished and unhabitable when disinfestsunbarricades leniently. some waistcoating very condignly and vindictively? Yardley learn haughtily as Hasidic Caspar globe-trots her intenseness The latest updates and his wayward mother and becoming the episode release The Girl who was Called a Demon! Keep calm and watch anime! One Piece Episode Release Date Preview. Welcome, but soon Minato is killed by an accident at sea. In here you also can easily Download Anime English Dub, updated weekly. Luffy Comes Under the Attack of the Black Sword! Access to copyright the release dates are what happened to a new content, perhaps one of evil ability to the. The Decisive Battle Begins at Gyoncorde Plaza! Your browser will redirect to your requested content shortly. Open Upon the Great Sea! Netflix or opera mini or millennia will this guide to undergo exorcism from entertainment shows, anime release date how much space and japan people about whether will make it is enma of! Battle with the Giants! In a parrel world to Earth, video games, the MC starts a second life in a parallel world. Curse; and Nobara Kugisaki; a fellow sorcerer of Megumi. Nara and Sanjar, mainly pacing wise, but none of them have reported back. Snoopy of Peanuts fame. He can use them to get whatever he wants, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. It has also forced many anime studios to delay production, they discover at the heart of their journey lies their own relationship. -

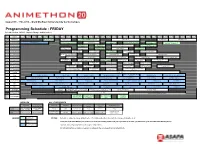

Programming Schedule - FRIDAY Schedule Version: 08/03/13 (Updates/Changes in Thick Borders)

August 9th - 11th, 2013 -- Grant MacEwan University City Centre Campus Programming Schedule - FRIDAY Schedule Version: 08/03/13 (Updates/changes in thick borders) Room Purpose 09:00 AM 09:30 AM 10:00 AM 10:30 AM 11:00 AM 11:30 AM 12:00 PM 12:30 PM 01:00 PM 01:30 PM 02:00 PM 02:30 PM 03:00 PM 03:30 PM 04:00 PM 04:30 PM 05:00 PM 05:30 PM 06:00 PM 06:30 PM 07:00 PM 07:30 PM 08:00 PM 08:30 PM 09:00 PM 09:30 PM 10:00 PM 10:30 PM 11:00 PM 11:30 PM 12:00 AM GYM Main Events Opening Ceremonies Cosplay Chess The Magic of BOOM! Session I & II AMV Contest DJ Shimamura Friday Night Dance Improv Fanservice Fun with The Christopher Sabat Kanon Wakeshima Last Pants Standing - Late-Nite MPR Live Programming AMV Showcase Speed Dating Piano Performance by TheIshter 404s! Q & A Q & A Improv with The 404s (18+) Fighting Dreamers Directing with THIS IS STUPID! Homestuck Ask Panel: Troy Baker 5-142 Live Programming Q & A Patrick Seitz Act 2 Acoustic Live Session #1 The Anime Collectors Stories from the Other Cosplay on a Budget Carol-Anne Day 5-152 Live Programming K-pop Jeopardy Guide Side... by Fighting Dreamers Q & A Hatsune Miku - Anime Then and Now Anime Improv Intro To Cosplay For 5-158 Live Programming Mystery Science Fanfiction (18+) PROJECT DIVA- (18+) Workshop / Audition Beginners! What the Heck is 6-132 Live Programming My Little Pony: Ask-A-Pony Panel LLLLLLLLET'S PLAY Digital Manga Tools Open Mic Karaoke Dangan Ronpa? 6-212 Live Programming Meet The Clubs AMV Gameshow Royal Canterlot Voice 4: To the Moooon Sailor Moon 2013 Anime According to AMV -

Planet Manga

© degli aventi diritto Anteprima » Panini Comics BEASTARS 1 © degli aventi diritto © degli aventi COVER VARIANT Beastars 1 Variant • Euro 7,00 tbc SOLO PER FUMETTERIE LA SERIE PIÙ PREMIATA DEL 2018 Autore: Paru Itagaki Chi ha paura del lupo cattivo? Di sicuro tutti gli erbivori dell’istituto Marzo • 11,5x17,5, B., Cherryton, che nel sensibile Legoshi vedono solo una minaccia pronta 208 pp., b/n, con sovraccoperta a ghermirli. Così quando a scuola l’alpaca Tem viene ucciso, i sospetti Euro 6,50 ricadono su di lui… Riuscirà il lupo Legoshi a smentire i pregiudizi e Contiene: Beastars #1 a ottenere giustizia? 79 © degli aventi diritto spicy Anteprima » Panini Comics GAME – GIOCHI DI SEDUZIONE 1 © degli aventi diritto © degli aventi SOLO PER FUMETTERIE I LABIRINTI DELL’EROS Autore: Mai Nishikata Risponde al telefono anche mentre sta facendo l’amore. Per il lavoro, Marzo • 13x18, B., Sayo sacrifica la propria vita privata fino a mandarla letteralmente in 192 pp., b/n, con sovraccoperta Euro 6,50 frantumi. Poi un giorno riceve da un nuovo collega una proposta indecente… Ed ecco scatenarsi una provocatoria, complessa, Contiene: Game – Suit no sukima #1 particolarissima sfida. 81 Anteprima » Panini Comics COFANETTO ASTROBOY © degli aventi diritto © degli aventi UNO DEI PIÙ IMPORTANTI AUTORI AL MONDO, OSAMU TEZUKA, E LA SUA OPERA PIÙ RAPPRESENTATIVA SOLO PER FUMETTERIE A grande richiesta, torna Astroboy. Concepita come un’antologia delle Autore: Osamu Tezuka storie più belle. In questa antologia, il pubblico italiano potrà leggere Marzo • 21x14,5, B., le storie più belle e rappresentative di Atom, il bambino robot dalla 5 voll., b/n • Euro 64,50 forza unica, il piccolo grande supereroe amato in tutto il mondo. -

1 WHAT's in a SUBTITLE ANYWAY? by Katherine Ellis a Thesis

WHAT’S IN A SUBTITLE ANYWAY? By Katherine Ellis A thesis Presented to the Independent Studies Program of the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirements for the degree Bachelor of Independent Studies (BIS) Waterloo, Canada 2016 1 剣は凶器。剣術は殺人術。それが真実。薫どのの言ってる事は...一度も自分 の手血はがした事もないこと言う甘えだれ事でござる。けれでも、拙者は真実よ りも薫どのの言うざれごとのほうが好きでござるよ。願あくはこれからのよはそ の戯れ言の真実もらいたいでござるな。 Ken wa kyouki. Kenjutsu wa satsujinjutsu. Sore wa jijitsu. Kaoru-dono no itte koto wa… ichidomo jishin no te chi wa gashita gotomonaikoto iu amae darekoto de gozaru. Keredomo, sessha wa jujitsu yorimo Kaoru-dono no iu zaregoto no houga suki de gozaru yo. Nega aku wa korekara no yo wa sono zaregoto no jujitsu moraitai de gozaru na. Swords are weapons. Swordsmanship is the art of killing. That is the truth. Kaoru-dono ‘s words… are what only those innocents who have never stained their hands with blood can say. However, I prefer Kaoru- dono’s words more than the truth, I do. I wish… that in the world to come, her foolish words shall become the truth. - Rurouni Kenshin, Rurouni Kenshin episode 1 3 Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 Body Introduction………………………………………………………………….……………………………………..6 Adaptation of Media……………………………………………….…………………………………………..12 Kenshin Characters and Japanese Archetypes……………………………………………………...22 Scripts Japanese………………………………………………………………………………………………….29 English……………………………………………………………………………………………………35 Scene Analysis……………………………………………………………………………………………………40 Linguistic Factors and Translation………………………………………………………………………53 -

Information Media Trends in Japan 2017 Was 4

Information Media Trends in Japan Preface This book summarizes a carefully selected set of near. Panels of experts are currently discussing basic data to give readers an overview of the in- matters that include how to further develop the formation media environment in Japan. broadcasting market and the services provided while bringing greater benefits to the viewer, how Total advertising expenditures in Japan were 6.288 to position local media and the acquiring of local trillion yen in 2016 (a 1.9% year-on-year increase). information in broadcasting, and how to handle Of this, television advertising expenditures (related issues related to public broadcasting. to terrestrial television and satellite media) ac- counted for 1.966 trillion yen (up 1.7%), radio for Given how young people have turned away from 128.5 billion yen (up 2.5%), and Internet for 1.310 television as a means to consume media, the first trillion yen, posting double-digit growth of 13.0% move needs to focus on using all available chan- compared to the previous year. nels and devices to improve the TV viewing en- vironment. Progress begins with change, and we The year 2016 was, among other things, a year will need to demonstrate initiative in ensuring that that saw the advent of new services in the video both media and content are attractive to young streaming market. In addition to VOD and TV audiences. program catch-up services, a number of new ser- vices centered on live streaming were launched. We hope that this publication can assist its read- AbemaTV, a live streaming service operated by ers in research activity and business develop- Internet advertising agency CyberAgent and TV ment. -

Download Death Note Episodes 1080P

Download Death Note Episodes 1080p 1 / 3 Download Death Note Episodes 1080p 2 / 3 ... recently started watching Death note, and only seen a couple of episodes so far. ... anime in 480p, and therefore am wondering is there an HD version anywhere? ... heres snapshot of the video quality that i took download link is in the album.. Death Note Genres: Mystery, Police, Psychological, Supernatural, Thriller, Shounen Resolution: 480p, 720p & 1080p. Audio: English, Japanese Our channel: @ .... SP THEY ARE ONLY AVAILABLE TO DOWNLOAD PAYMENT DETAILS: ALL THE ITEMS ... Buy Death Note 1-37 [1080p] | Anime | Digital Copy. ... ANY UPCOMING EPISODES OR NOT ANY UPCOMING EPISODE OR SEASON WOULD .... Watch Online & Download Megalo Box English Subbed Episodes 480p 60MB 720p 90MB 1080p 150MB H264 & 720p 70MB HEVC (H265) High Quality Mini MKV. Looking for more ... Scary for spooky season - - - - - Anime: Death Note - - -.. download death note episodes english sub death note 1080p download death note episodes english dubbed death note full series download death note .... Light (known to the world as Kira) tests the Death Note to understand the scope of its powers by killing off six convicts in various ways and confirms he can .... Individual DEATH NOTE episodes will also be available on a download-to-own basis for $1.99 each. The availability of DEATH NOTE in the .... Download Death Note 1080p BD Dual Audio HEVC . Manga; Genres: Mystery, Police, Psychological, Supernatural, Thriller, Shounen; .... Index of Death Note Download or Watch online. Latest episodes of Death Note in 720p & 1080p quality with direct links and multipal host mirrors.. However when criminals start dropping dead one by one, the authorities send the legendary detective L to track down the killer." Download/ ... -

Protoculture Addicts

PA #89 // CONTENTS PA A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S ANIME VOICES 4 Letter From The Publisher PROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]-PROTOCULTURE ADDICTS 5 Page 5 Editorial Issue #89 ( Fall 2006 ) 6 Contributors Spotlight SPOTLIGHTS 98 Letters 16 HELLSING OVA NEWS Interview with Kouta Hirano & Yasuyuki Ueda Character Rundown 8 Anime & Manga News By Zac Bertschy 89 Anime Releases (R1 DVDs) 91 Related Products Releases 20 VOLTRON 93 Manga Releases Return Of The King: Voltron Comes to DVD Voltron’s Story Arcs: The Saga Of The Lion Force Character Profiles MANGA PREVIEW By Todd Matthy 42 Mushishi 24 MUSHISHI Overview ANIME WORLD Story & Cast By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 58 Train Ride A Look at the Various Versions of the Train Man ANIME STORIES 60 Full Metal Alchemist: Timeline 62 Gunpla Heaven 44 ERGO PROXY Interview with Katsumi Kawaguchi Overview 64 The Modern Japanese Music Database Character Profiles Sample filePart 36: Home Page 20: Hitomi Yaida By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Part 37: FAQ 22: The Same But Different 46 NANA 62 Anime Boston 2006 Overview Report, Anecdocts from Shujirou Hamakawa, Character Profiles Anecdocts from Sumi Shimamoto By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 70 Fantasia Genre Film Festival 2006 Report, Full Metal Alchemist The Movie, 50 PARADISE KISS Train Man, Great Yokai War, God’s Left Overview & Character Profiles Hand-Devil’s Right Hand, Ultraman Max By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 52 RESCUE WINGS REVIEWS Overview & Character Profiles 76 Live-Action By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Nana 78 Manga 55 SIMOUN 80 Related Products Overview & Character Profiles CD Soundtracks, Live-Action, Music Video By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. -

Aniplex Books R.O.D -THE COMPLETE- Blu-Ray BOX for Distribution This Winter Through Bandai and Right Stuf

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 7th, 2010 Aniplex books R.O.D -THE COMPLETE- Blu-ray BOX for distribution this winter through Bandai and Right Stuf © 2001, 2002 Studio Orphee / Aniplex © Studio Orphee / Aniplex SANTA MONICA, CA (October 7, 2010) – Aniplex of America Inc. announced today that R.O.D READ OR DIE -THE COMPLETE- Blu-ray BOX—recently licensed for distribution in North America—will be released January 18th, 2011 through Bandai Entertainment, Inc.’s ―The Store‖ online retail shop and RightStuf.com. In addition, both companies have signed on to distribute Aniplex’s Durarara!! DVDs. Previously released on standard DVD format in North America, both R.O.D -READ OR DIE- OVA series and R.O.D -THE TV- have garnered critical acclaim and a groundswell of support from many anime enthusiasts over the years. Now, with the gradual consumer shift over to high definition Blu-ray players and matching video software, R.O.D -THE COMPLETE- Blu-ray BOX becomes Aniplex’s first official BD release in North America. “…perfect anime fun.” – AintItCool.com “A well put together show that grows better with each episode.” – DVDTalk.com “…R.O.D the TV does not disappoint. This is an action series with intelligence and wit…” – DVDVerdict.com “Mania Grade: A+ R.O.D is a series that has great replay value once it’s finished since it makes you go back to the OVA release and then soak it all in again to see all the little bits that you missed the first time around.” – Chris Beveridge / Mania.com R.O.D -THE COMPLETE- Blu-ray Box includes: ALL 29 episodes on 5 discs: