'Lje[Ta-'Estuary Ca{Ijornias In{Ancf Coast .521

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0 5 10 15 20 Miles Μ and Statewide Resources Office

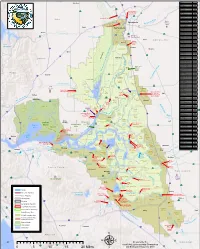

Woodland RD Name RD Number Atlas Tract 2126 5 !"#$ Bacon Island 2028 !"#$80 Bethel Island BIMID Bishop Tract 2042 16 ·|}þ Bixler Tract 2121 Lovdal Boggs Tract 0404 ·|}þ113 District Sacramento River at I Street Bridge Bouldin Island 0756 80 Gaging Station )*+,- Brack Tract 2033 Bradford Island 2059 ·|}þ160 Brannan-Andrus BALMD Lovdal 50 Byron Tract 0800 Sacramento Weir District ¤£ r Cache Haas Area 2098 Y o l o ive Canal Ranch 2086 R Mather Can-Can/Greenhead 2139 Sacramento ican mer Air Force Chadbourne 2034 A Base Coney Island 2117 Port of Dead Horse Island 2111 Sacramento ¤£50 Davis !"#$80 Denverton Slough 2134 West Sacramento Drexler Tract Drexler Dutch Slough 2137 West Egbert Tract 0536 Winters Sacramento Ehrheardt Club 0813 Putah Creek ·|}þ160 ·|}þ16 Empire Tract 2029 ·|}þ84 Fabian Tract 0773 Sacramento Fay Island 2113 ·|}þ128 South Fork Putah Creek Executive Airport Frost Lake 2129 haven s Lake Green d n Glanville 1002 a l r Florin e h Glide District 0765 t S a c r a m e n t o e N Glide EBMUD Grand Island 0003 District Pocket Freeport Grizzly West 2136 Lake Intake Hastings Tract 2060 l Holland Tract 2025 Berryessa e n Holt Station 2116 n Freeport 505 h Honker Bay 2130 %&'( a g strict Elk Grove u Lisbon Di Hotchkiss Tract 0799 h lo S C Jersey Island 0830 Babe l Dixon p s i Kasson District 2085 s h a King Island 2044 S p Libby Mcneil 0369 y r !"#$5 ·|}þ99 B e !"#$80 t Liberty Island 2093 o l a Lisbon District 0307 o Clarksburg Y W l a Little Egbert Tract 2084 S o l a n o n p a r C Little Holland Tract 2120 e in e a e M Little Mandeville -

Transitions for the Delta Economy

Transitions for the Delta Economy January 2012 Josué Medellín-Azuara, Ellen Hanak, Richard Howitt, and Jay Lund with research support from Molly Ferrell, Katherine Kramer, Michelle Lent, Davin Reed, and Elizabeth Stryjewski Supported with funding from the Watershed Sciences Center, University of California, Davis Summary The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta consists of some 737,000 acres of low-lying lands and channels at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (Figure S1). This region lies at the very heart of California’s water policy debates, transporting vast flows of water from northern and eastern California to farming and population centers in the western and southern parts of the state. This critical water supply system is threatened by the likelihood that a large earthquake or other natural disaster could inflict catastrophic damage on its fragile levees, sending salt water toward the pumps at its southern edge. In another area of concern, water exports are currently under restriction while regulators and the courts seek to improve conditions for imperiled native fish. Leading policy proposals to address these issues include improvements in land and water management to benefit native species, and the development of a “dual conveyance” system for water exports, in which a new seismically resistant canal or tunnel would convey a portion of water supplies under or around the Delta instead of through the Delta’s channels. This focus on the Delta has caused considerable concern within the Delta itself, where residents and local governments have worried that changes in water supply and environmental management could harm the region’s economy and residents. -

New England Retreat

2011 California Switzer Fellows Retreat Agenda DRAFT FRIDAY, September 30 th (Evening arrival for all 2011 California Fellows and out of town travelers. New Fellows please arrive in tme for dinner!) 5:00 pm Check-in 6 :00 – 7:00 pm DINNER 7:00 – 9:00 pm INTRODUCTIONS, ORIENTATION FOR NEW FELLOWS. This evening will allow tme for welcoming and introductons for new Fellows, as well as presentaton of leadership concepts to be explored throughout the weekend. Fellows will have a chance to identfy topics for networking over the weekend. Partcipant and staf introductons will be made. SATURDAY, October 1 st 8:00 – 9:00 am BREAKFAST and check-in for new arrivals 9:00 – 9:15 am INTRODUCTIONS. Lissa Widof, Executve Director of the Switzer Foundaton, will welcome partcipants and introduce the Communicatons training, trainers and context for this work. 9:15 – 12:30 TRAINING: MESSAGING AND COMMUNICATIONS We ofer this training at the fall retreat as the frst step in our efort to help Fellows develop efectve communicatons skills. For these trainings, we have the great privilege of engaging with a terrifc group of trainers and practtoners. Liz Neeley of COMPASS (Communicaton Partnership for Science and the Sea) specializes in training scientsts and experts to hone their messages so they can communicate their work to a wide range of audiences. The morning session will include training with actve feld journalists and topics such as - Welcome to My World – real world stories from professional journalists - Bridging the worlds of science and journalism - Show Don’t Tell: The Storytelling Process - An introducton to messaging using a tool called the Message Box, a simple yet powerful tool for organizing and focusing any message for any audience that will be useful beyond the workshop setng. -

The MCL “North Marin Unit” Always Has a Full Plate

May-June 2009 May-June 2009 EDITORIAL Focus on North Marin Is the MTC too HOT to Trot? Why The MCL MCL is Concerned About HOT Lanes “North Marin The long- awaited Unit” Always Highway 101 Gap Closure project’s HOV Has a Full Plate lanes, funded by Susan Stompe and Nona Dennis by Measure A, could Geographic “Units” of Marin potentially Conservation League be converted to HOT lanes When Marin Conservation League was under the launched by its founders as the “Marin MTC plan County Survey Committee” in late 1934, one of the fi rst objectives was to engage rep- resentatives from all parts of the county in photo: Dru Parker planning for its future. As the “Committee” evolved into “Marin Conservation League” n occasion, Marin Conservation The claimed attractions of the concept are and gained wide support, the representation OLeague fi nds itself questioning threefold: coalesced into geographic units – initially whether “the Emperor is wearing any It expands mobility options by providing Mill Valley, San Rafael, West Marin, and clothes” – or, put another way: is the pub- an opportunity for reliable travel times to then North Marin and Rural Land Use. At a lic being given all the facts while a grand users willing to pay a signifi cant premium time when there were few environmental plan is rushed forward with inadequate for this service (hence the nickname, organizations in the county, the League’s public education? The current discussion “Lexus Lanes”); Units provided an opportunity for people about implementing High Occupant Toll in a region to get together to discuss local (HOT) Lanes along 800 miles of Bay Area HOT lanes generate a source of revenue, issues, track local developments, meet with freeways seems to fall into this category. -

Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and McCarthy Center Student Scholarship the Common Good 2020 Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference David Donahue Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/mccarthy_stu Part of the History Commons CHANGEMAKERS AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE Biographies inspired by San Francisco’s Ella Hill Hutch Community Center murals researched, written, and edited by the University of San Francisco’s Martín-Baró Scholars and Esther Madríz Diversity Scholars CHANGEMAKERS: AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE © 2020 First edition, second printing University of San Francisco 2130 Fulton Street San Francisco, CA 94117 Published with the generous support of the Walter and Elise Haas Fund, Engage San Francisco, The Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good, The University of San Francisco College of Arts and Sciences, University of San Francisco Student Housing and Residential Education The front cover features a 1992 portrait of Ella Hill Hutch, painted by Eugene E. White The Inspiration Murals were painted in 1999 by Josef Norris, curated by Leonard ‘Lefty’ Gordon and Wendy Nelder, and supported by the San Francisco Arts Commission and the Mayor’s Offi ce Neighborhood Beautifi cation Project Grateful acknowledgment is made to the many contributors who made this book possible. Please see the back pages for more acknowledgments. The opinions expressed herein represent the voices of students at the University of San Francisco and do not necessarily refl ect the opinions of the University or our sponsors. -

2010-2011 Course Listings

A n n u a l R e p o r t 2 0 1 UCLA 0 Institute - for Research 2 0 on Labor and 1 Employment 1 Table of Contents Letter from the Director.....................................................................................................................1 About IRLE.........................................................................................................................................2 History................................................................................................................................................3 Governance.........................................................................................................................................5 Governance Structure.......................................................................................................6 IRLE Leadership................................................................................................................8 Department Organization Chart.....................................................................................9 Staff Awards .......................................................................................................................10 Financial Issues .................................................................................................................11 Extramural Support..........................................................................................................12 Academic Activities...........................................................................................................................13 -

Draft Environmental Assessment for the Shiloh Iii Wind Plant Project Habitat Conservation Plan

DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FOR THE SHILOH III WIND PLANT PROJECT HABITAT CONSERVATION PLAN P REPARED BY: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 2800 Cottage Way, W-2650 Sacramento, CA 95825 Contact: Mike Thomas, Chief Habitat Conservation Planning Branch W ITH TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE FROM: ICF International 630 K Street, Suite 400 Sacramento, CA 95814 Contact: Brad Schafer 916.737.3000 February 2011 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Draft Environmental Assessment for the Shiloh III Wind Plant Project Habitat Conservation Plan. February. (ICF 00263.09). Sacramento, CA. With technical assistance from ICF International, Sacramento, CA. Contents Chapter 1 Purpose and Need ........................................................................................................... 1‐1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................................ 1‐1 1.2 Species Covered by the HCP ...................................................................................................... 1‐2 1.3 Proposed Action Addressed in this EA ....................................................................................... 1‐2 1.4 Purpose of and Need for the Proposed Action .......................................................................... 1‐2 Chapter 2 Proposed Action and Alternatives .................................................................................. 2‐1 2.1 Alternative 1: Proposed Action ................................................................................................. -

Draft Upper San Joaquin River Basin Storage Investigation

Draft Feasibility Report Upper San Joaquin River Basin Storage Investigation Prepared by: United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Mid-Pacific Region U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation January 2014 Mission Statements The mission of the Department of the Interior is to protect and provide access to our Nation’s natural and cultural heritage and honor our trust responsibilities to Indian Tribes and our commitments to island communities. The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. Executive Summary The Upper San Joaquin River Basin Storage This Draft Feasibility Report documents the Investigation (Investigation) is a joint feasibility of alternative plans, including a range feasibility study by the U.S. Department of of operations and physical features, for the the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation potential Temperance Flat River Mile 274 (Reclamation), in cooperation with the Reservoir. California Department of Water Resources Key Findings to Date: (DWR). The purpose of the Investigation is • All alternative plans would provide benefits to determine the potential type and extent of for water supply reliability, enhancement of Federal, State of California (State), and the San Joaquin River ecosystem, and other resources. regional interest in a potential project to • All alternative plans are technically feasible, expand water storage capacity in the upper constructible, and can be operated and San Joaquin River watershed for improving maintained. water supply reliability and flexibility of the • Environmental analyses to date suggest that water management system for agricultural, all alternative plans would be urban, and environmental uses; and environmentally feasible. -

Historic, Recent, and Future Subsidence, Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, California, USA

UC Davis San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science Title Historic, Recent, and Future Subsidence, Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, California, USA Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7xd4x0xw Journal San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science, 8(2) ISSN 1546-2366 Authors Deverel, Steven J Leighton, David A Publication Date 2010 DOI https://doi.org/10.15447/sfews.2010v8iss2art1 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7xd4x0xw#supplemental License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California august 2010 Historic, Recent, and Future Subsidence, Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, California, USA Steven J. Deverel1 and David A. Leighton Hydrofocus, Inc., 2827 Spafford Street, Davis, CA 95618 AbStRACt will range from a few cm to over 1.3 m (4.3 ft). The largest elevation declines will occur in the central To estimate and understand recent subsidence, we col- Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta. From 2007 to 2050, lected elevation and soils data on Bacon and Sherman the most probable estimated increase in volume below islands in 2006 at locations of previous elevation sea level is 346,956,000 million m3 (281,300 ac-ft). measurements. Measured subsidence rates on Sherman Consequences of this continuing subsidence include Island from 1988 to 2006 averaged 1.23 cm year-1 increased drainage loads of water quality constitu- (0.5 in yr-1) and ranged from 0.7 to 1.7 cm year-1 (0.3 ents of concern, seepage onto islands, and decreased to 0.7 in yr-1). Subsidence rates on Bacon Island from arability. -

A Century of Delta Salt Water Barriers

A Century of Salt Water Barriers in the Delta By Tim Stroshane Policy Analyst Restore the Delta June 5, 2015 edition Since the late 19th century, California’s basic plan for water resource development has been to export water from the Sacramento River and the Delta to the San Joaquin Valley and southern California. Unfortunately, this basic plan ignores the reality that the Delta is the very definition of an estuary: it is where fresh water from the Central Valley’s rivers meets salt water from tidal flow to the Delta from San Francisco Bay. Productive ecosystems have thrived in the Delta for millenia prior to California statehood. But for nearly a century now, engineers and others have frequently referred to the Delta as posing a “salt menace,” a “salinity problem” with just two solutions: either maintain a predetermined stream flow from the Delta to Suisun Bay to hydraulically wall out the tide, or use physical barriers to separate saline from fresh water into the Delta. While readily admitting that the “salt menace” results from reduced inflows from the Delta’s major tributary rivers, the state of California uses salt water barriers as a technological fix to address the symptoms of the salinity problem, rather than the root causes. Given complex Delta geography, these two main solutions led to many proposals to dam up parts of San Francisco Bay, Carquinez Strait, or the waterway between Chipps Island in eastern Suisun Bay and the City of Antioch, or to use large amounts of water—referred to as “carriage water”— to hold the tide literally at bay. -

Go Outside and Play!

Go Outside and Play! Department of Regional Parks 10361 Rockingham Dr, Ste 100, Sacramento, CA 95827 (916) 875-6961 www.sacparks.net Annual Regional Parks Passes Available 1. Vehicle $50.00 2. Motorized Vessel/Trailer/Oversize Vehicle $100.00 3. Non-Motorized Vessel (kayak, canoe, etc) $30.00 *Vehicle Annual Pass purchased separately 4. Vehicle with Horse Trailer (trailer allowed in equestrian staging areas only) $75.00 Prices subject to change WHERE TO PURCHASE AN ANNUAL PASS Regional Parks Office (10361 Rockingham Dr, Ste 100) in Rancho Cordova American River Parkway Foundation Office (5700 Arden Way) in William B. Pond Recreation Area Effie Yeaw Nature Center (2850 San Lorenzo Way) in Ancil Hoffman Park Call 916-875-6961 To request an application by mail Purchase online www.arpf.org Multiple local retailers offer the Annual Pass for sale. For a complete list, please visit www.arpf.org Credit cards are accepted through the website, the American River Parkway Foundation Office, and the Regional Parks Office. Please make checks payable to Sacramento County. 1 of 2 REGIONAL PARKS PASS STIPULATIONS NO REFUNDS — NO REPLACEMENTS Passes are valid for a 12-month period from month purchased. Passes are valid for one vehicle entry only. A pass does not guarantee entry into parks that are full or closed for any reason, Check #_________ _______________ Horse Trailer including inclement weather or flooding and is not valid for entry to special fee __________ $_____________ areas or special events. _______________ Cash Cash All passes must be displayed from the rear-view mirror or placed where they are Pass #__________________ visible from the vehicle’s front exterior. -

Municipal Water Quality Investigations Program History and Studies 1983—2012

State of California The Resources Agency Department of Water Resources Municipal Water Quality Investigations Program History and Studies 1983—2012 November 2013 Edmund Brown Jr. John Laird Mark W. Cowin Governor Secretary for Resources Director State of California The Resources Agency Department of Water Resources State of California Edmund G. Brown Jr., Governor California Natural Resources Agency John Laird, Secretary for Natural Resources Department of Water Resources Mark W. Cowin, Director Laura King Moon, Chief Deputy Director Office of the Chief Counsel Public Affairs Office Security Operations Cathy Crothers Nancy Vogel, Ass't Dir. Sonny Fong Gov't & Community Liaison Policy Advisor Legislative Affairs Office Kimberly Johnston~ Dodds Waiman Yip Kasey Schimke, Ass't Dir. Deputy Directors Paul Helliker Delta and Statewide Water Management Gary Bardini Integrated Water Management Carl Torgersen State Water Project John Pacheco California Energy Resources Scheduling Kathie Kishaba Business Operations Division of Environmental Services Dean F. Messer, Chief Office of Water Quality Stephani Spaar, Chief Municipal Water Quality Program Branch Municipal Water Quality Investigations Section Cindy Garcia, Chief Rachel Pisor, Chief Ofelia Bogdan, Staff Services Analyst Prepared By Sonia Miller, Project Leader Otome J. Lindsey Foreword The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta (Delta) is a major source of drinking water for 25 million people of the State of California. Therefore, the quality of Delta water is an important consideration for its use as a drinking water source. However, Delta water quality may be degraded by a variety of sources and environmental factors. Close monitoring of Delta waters is necessary to ensure delivery of high quality source waters to urban water suppliers.