02Whole.Pdf (PDF, 362.25KB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume – 25 Number – 3 September to November 2018 Edition

Volume – 25 Number – 3 September to November 2018 Edition Steam locomotive 3801 (4-6-2) was operated by the New South Wales Government Railways between 1943 and 1976. It is arguably Australia’s most famous steam locomotive, being the only one to have visited all main line states and territories. The 38 Class numbered 30. The first 5 units, with the streamlined design, were built by Clyde Engineering, Granville, New South Wales. The other 25 units were built, semi-streamlined, at the New South Wales Eveleigh (even numbers) and Cardiff (odd numbers) Locomotive Workshops. 3801 entered service on 22 January 1943 and worked the “Newcastle Flyer” for the first time on 23 February 1943 to express passengers to and from Sydney. 2018 celebrates the 75th anniversary of this iconic steam locomotive. See page 9 for a history and restoration update. Image – Wikipedia – 3801 leads the Newcastle Flyer on 1 October 2005 1 OFFICE BEARERS President: Daniel Cronin Secretary: David Patrick Treasurer: Geoff Crow Membership Officer: David Patrick Electrical Engineer: Ben Smith Way & Works Engineer: Ben Smith Mechanical Engineer: Warwick Brisbane Development Engineer: Peter Riggall Club Rooms: Old Parcels Office Auburn Railway Station Victoria Road Auburn Telephone: 0419 414 309 Friday evenings Web Address: www.mmrs.org.au Web Master: Mark Johnson Call Board Production: John Ford Meetings: Friday evenings at 7:30 pm Committee Meetings 2nd Tuesday of the month (Refer to our website for our calendar of events) Index Page: 3 AGM Meeting Notice Page: 4 President’s Report Page: 6 What’s Happening Page: 7 Naradhan Images: Caulfield August 2018 Page: 9 Feature Article: History of Steam Locomotive 3801 Page: 14 Calendars for September 2018 to November 2018 2 THE 53rd ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING OF THE MELBOURNE MODEL RAILWAY SOCIETY INC WILL BE HELD AT 8.00 PM ON FRIDAY OCTOBER 19th, 2018 AT THE MMRS CLUB ROOMS VICTORIA STREET, HAWTHORN (at the Auburn railway station) Business: A. -

David Hill, by David Hill, the Other David Hill, David Dale, Mr

The Times January 2019 A journal of transport timetable history and analysis RRP $4.95 Inside: That Scrofulous Cad Incl. GST Timetables of Australia and New Zealand The Times A journal of the Australian Timetable Association Inc. (A0043673H) Print Publication No: 349069/00070, ISSN 0813-6327 January 2019 Vol 36 No. 01, Issue No. 420 The Times welcomes all contributions. Our Authors’ Guide is available on our web-site at https://www.timetable.org.au/ Reproduction Provided a Creative Commons acknowledgement is made, material appearing in The Times may be repro- duced anywhere. Disclaimer Opinions expressed in our magazines are not necessarily those of the Association or its members. Editor Geoff Lambert 179 Sydney Rd FAIRLIGHT 2094 NSW email: [email protected] The Times is posted in full colour to our website https://www.timetable.org.au/times.html, two months after publi- cation in paper and to the National Library website 6 months after publication. Colour PDF versions of previous issues of our magazines are at http://www.austta.org.au —Contents— Various THE BLUE CHEESE THEFT 3 Geoff Lambert & Noel Farr ANZR PTT 7 There is no such a font The Art Deco style timetable shown on our pages 7-12 has many interesting aspects—one of which is the typography. The “What the Font” web-site cannot identify it. Art Deco fonts were all the rage for railways of that era - most notably Gill Sans, which was actually created for a railway—the LNER—by Eric Gill. The text illustrated above appears to be an attempt by the Victorian Railways printing works at North Melbourne to create its own font style. -

'Ugly Sydney' Or an Enhancement of the Greatest Rail

Australian Folklore 21, 2006 157 The Fate of Eveleigh: More of ‘Ugly Sydney’ or an Enhancement of the Greatest Rail Heritage Site in the World? Brian Dunnett and Robert J. Haworth Lovers of heritage and of a human-scale city alike are alarmed at the latest proposal for the old Eveleigh Railway Workshops site that covers many hectares of inner Sydney.1 The New South Wales Government Planning Minister Frank Sartor has recently excised the area from heritage protection legislation in order to allow maximum possible development of the site for high-rise apartment blocks.2 Of particular concern is the current threat3 to close the still functioning Large Erecting Shed and transform it into either a completely new 12 storey office tower or an ‘adaptive re-use’ four storey block. Unfortunately, the concerns of community groups, even if they represent a majority of citizens, mean little to contemporary Governments, especially at the State level. This is particularly true of the New South Wales Government, which is in the perverse position, after 15 years of uninterrupted economic boom, of being squeezed between accelerated development brought on by the boom and declining tax revenue4 exacerbated by the increasingly unequal power distribution between the States and Canberra. Developer Section 94 contributions allowed for under the NSW EPA Act5 go to Local Government, thus giving the State Minister an incentive to excise choice areas and over- develop them as a means of much-needed revenue raising from special developers’ contributions which go direct to the State Government. The 1 The best pictorial presentation of is in danger of being lost is in: D. -

HUT NEWS Issue No

Blue Mountains Conservation Society Inc. Issue No. 333 HUT NEWS February 2016 “Nature Conservation Saves for Tomorrow” FEATURE DOCUMENTARY BLACK HOLE THURSDAY, 25th February, 7 pm Transforming a Forest into a Coal Mine at the CONSERVATION HUT, Wentworth Falls BLACK HOLE is an intensely riveting Have you joined the Society recently and exposé of the ongoing battle to save would like to meet other members? the last of an endangered woodland Are you a long-standing member who forest from being cleared to make way would like to get to know and exchange to one of the largest open cut coal ideas with some of our newer recruits? mines in production in Australia. Are you thinking about joining the Society, The Leard State Forest has stunning but would like to know more about it? old growth box-gum woodland and is considered a national biodiversity Then this special evening is for you. hotspot. In total the mines would turn You are invited to join us over a cuppa and share one of the best sunset 3500 hectares of forest into an open- views to be had in our glorious Blue Mountains. (The views are fantastic, cut mine pit. even without a sunset!) The campaign to save it is a piece of Meet old and new friends ... meet some of the Society’s management Australian history, being spoken in the committee and find out what they have been doing over the past year; find same breath as iconic environmental out how you can get involved. campaigns in Australian history, such The Conservation Hut is in the Blue Mountains National Park at the end of as the Franklin River Blockade in Fletcher Street, Wentworth Falls. -

Progress in Rail Reform Inquiry Report

Progress in Rail Reform Inquiry Report Report No. 6 5 August 1999 Commonwealth of Australia 1999 ISBN 0 646 33597 9 This work is subject to copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, the work may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes, subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source. Reproduction for commercial use or sale requires prior written permission from AusInfo. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Manager, Legislative Services, AusInfo, GPO Box 1920, Canberra, ACT, 2601. Publications Inquiries: Media and Publications Productivity Commission Locked Bag 2 Collins Street East Melbourne VIC 8003 Tel: (03) 9653 2244 Fax: (03) 9653 2303 Email: [email protected] General Inquiries: Tel: (03) 9653 2100 or (02) 6240 3200 An appropriate citation for this paper is: Productivity Commission 1999, Progress in Rail Reform, Inquiry report no. 6, AusInfo, Canberra. The Productivity Commission The Productivity Commission, an independent Commonwealth agency, is the Government’s principal review and advisory body on microeconomic policy and regulation. It conducts public inquiries and research into a broad range of economic and social issues affecting the welfare of Australians. The Commission’s independence is underpinned by an Act of Parliament. Its processes and outputs are open to public scrutiny and are driven by concern for the wellbeing of the community as a whole. Information on the Productivity Commission, its publications and its current work program can be found on the World Wide Web at www.pc.gov.au or by contacting Media and Publications on (03) 9653 2244. -

Section 10 Locomotive and Rolling Stock Data

General Instruction Pages Locomotive and Rolling Stock Data SECTION 10 LOCOMOTIVE AND ROLLING STOCK DATA General Instruction Pages Locomotive and Rolling Stock Data SECTION 10 Contents 3801 Limited Eveleigh - Locomotives................................................................................................................3 3801 Limited Eveleigh - Passenger Rolling Stock...............................................................................................3 3801 Limited Eveleigh - Freight Rolling Stock ...................................................................................................3 Australian Traction Corporation - Locomotives ................................................................................................3 Australian Traction Corporation - Freight Rolling Stock....................................................................................3 Australian Railway Historical Society A.C.T. Division – Locomotives................................................................3 Australian Railway Historical Society A.C.T. Division – Rail Motors ..................................................................4 Australian Railway Historical Society A.C.T. Division – Passenger Rolling Stock...............................................4 Australian Railway Historical Society A.C.T. Division – Freight Rolling Stock....................................................4 Australian Rail Track Corporation Ltd - Special Purpose Rolling Stock..............................................................4 -

State Capital Program 1997-98

NEW SOUTH WALES STATE CAPITAL PROGRAM 1997-98 Budget Paper No. 4 CONTENTS Page 1. STATE CAPITAL PROGRAM 1.1 Overview ............................................................................................... 1 1.2 Expenditure Trends .............................................................................. 2 1.3 1996-97 Program Outcome ................................................................ 3 1.4 1997-98 Program ................................................................................ 4 1.5 Funding of State Capital Program ............ .................................... 5 2. NON BUDGET SECTOR PROGRAM 2.1 Overview ............................................................................................... 8 2.2 1996-97 Expenditure ........................................................................... 8 2.3 1997-98 Expenditure ........................................................................... 9 3. CAPITAL PROJECTS 3.1 Introduction .......................................................................................... 15 3.2 Budget Sector Capital Projects (incl. agency index) .............................................................................. 17 3.3 Non Budget Sector Capital Projects (incl. agency index) .............................................................................. 83 4. AGENCY CONTACTS .............................................................. 131 1 1. STATE CAPITAL PROGRAM 1.1 OVERVIEW The State capital program comprises capital payments of both the Budget and -

The Railway Line to Broken Hill

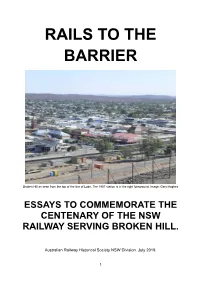

RAILS TO THE BARRIER Broken Hill as seen from the top of the line of Lode. The 1957 station is in the right foreground. Image: Gary Hughes ESSAYS TO COMMEMORATE THE CENTENARY OF THE NSW RAILWAY SERVING BROKEN HILL. Australian Railway Historical Society NSW Division. July 2019. 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION........................................................................................ 3 HISTORY OF BROKEN HILL......................................................................... 5 THE MINES................................................................................................ 7 PLACE NAMES........................................................................................... 9 GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE....................................................................... 12 CULTURE IN THE BUILDINGS...................................................................... 20 THE 1919 BROKEN HILL STATION............................................................... 31 MT GIPPS STATION.................................................................................... 77 MENINDEE STATION.................................................................................. 85 THE 1957 BROKEN HILL STATION................................................................ 98 SULPHIDE STREET STATION........................................................................ 125 TARRAWINGEE TRAMWAY......................................................................... 133 BIBLIOGRAPHY.......................................................................................... -

New South Wales from 1810 to 1821

Attraction information Sydney..................................................................................................................................................................................2 Sydney - St. Mary’s Cathedral ..............................................................................................................................................3 Sydney - Mrs Macquarie’s Chair ..........................................................................................................................................4 Sydney - Hyde Park ..............................................................................................................................................................5 Sydney - Darling Harbour .....................................................................................................................................................7 Sydney - Opera House .........................................................................................................................................................8 Sydney - Botanic Gardens ................................................................................................................................................. 10 Sydney - Sydney Harbour Bridge ...................................................................................................................................... 11 Sydney - The Rocks .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Don't Throw the Baby out with the Bathwater! Submission to the NSW Department of Planning Regarding the Eveleigh Workshops

Don’t Throw the Baby Out with the Bathwater! Submission to the NSW Department of Planning Regarding the Eveleigh Workshops Site, Redfern: the North Eveleigh Concept Plan. Prepared by Brian Dunnett, Co-ordinator of the ‘Trains of Treasure’ Historical Railway Exhibition, 1985. With assistance from the following people with an active interest in New South Wales Railway Heritage: Robert Haworth - Heritage Futures Research Centre, The University of New England Bob Rymes Eveleigh Locomotive Workshop Union Stewards Committee 1950’s and other committee members from that time. Introduction The following comments on the heritage features of the concept plan from the Redfern Waterloo Authority for the North Eveleigh Site are made with a personal knowledge of the history of the North Eveleigh and the Eveleigh site (as a whole), and the understanding reached between the former workforce, the then NSW Labour Council, State Rail, and the NSW Government in the early 1980’s concerning the protection of railway heritage that was located there. My knowledge of many heritage features of the Eveleigh Workshops has been accumulated over 70 years both through a long family association with the site, and personally as an electrical apprentice and tradesperson, a State Rail Workshop Communication Officer in the late 1980’s, and later University study and research into rail heritage. This submission is also presented with an awareness of the failure of the NSW Government and its Departments (mainly State Rail and RailCorp) to protect the international, national and state heritage status of the site since it was closed in the 1980’s. Some details of this chain of events and broken agreements on the site’s heritage status and future that have allowed this situation to occur can be found by close reading of the Heritage Impact Statement prepared as part of the concept plan by Weir and Philips – Architects and Heritage Consultants. -

Working Paper 54 – Regional Public Transport in Australia

Bureau of Transport and Regional Economics WORKING PAPER 54 REGIONAL PUBLIC TRANSPORT IN AUSTRALIA: ECONOMIC REGULATION AND ASSISTANCE MEASURES Commonwealth of Australia 2003 ISSN 1440-9707 ISBN 1-877081-25-6 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction rights should be addressed to the Manager, Legislative Services, AusInfo, GPO Box 84, Canberra, ACT 2601. This publication is available free of charge from the Bureau of Transport and Regional Economics, GPO Box 501, Canberra, ACT 2601, by downloading it from our website (see below), by phone (02) 6274 7210, fax (02) 6274 6816 or email: [email protected] http://www.btre.gov.au Disclaimers The BTRE seeks to publish its work to the highest professional standards. However, it cannot accept responsibility for any consequences arising from the use of information herein. Readers should rely on their own skill and judgement in applying any information or analysis to particular issues or circumstances. FOREWORD Regional public transport plays an important role in meeting the needs of Australians for access to essential services and for mobility. This paper provides a snapshot of the Commonwealth and state/territory governments’ regulatory and assistance arrangements affecting long-distance regional public transport across Australia in 2001–02. The aim of the paper is to provide information to inform government policy on long-distance regional public transport services. The paper complements the BTRE’s earlier research into regional public transport—Regional Public Transport in Australia: Long-distance Services, Trends and Projections—which was released in March 2003. -

DECEMBER 1985 NEWS and VIEWS Volume 9 Number 4 the Newslefter of the Public Transport Users'association Incorporated

tssN 0815-189X PTUA NEWSLETTER TRANSIT DECEMBER 1985 NEWS AND VIEWS Volume 9 Number 4 The Newslefter of the Public Transport Users'Association Incorporated. Registered by Aushalia Post - Publication No. VBG 3534 2 TRANSIT NEWS.N.VIEWS The Publlc Traneport Ueere' Accoclatlon EDITORIAL Role of the PTUA *;31'il:'u:5 The PTUA is a voluntary, non-party policical, tt.tr profit' organization of public transport users. Mr Roper has some off-beat ideas about the role of a community group like the PTUA. ing) Doug.-Sherman lts fuiction is to lobbu the Government fot n During his address the sll'l tl _ to PTUA's Annual General Meeting in September, he said that the acknowledge in the same issue PTUA should offer more conshuctive help instead of engaging in pie-throwing. lhose tireless workers who assemble the Newsletter t',1:;' Mr Roper seems to think that the PTUA exists just to throw pies pies, .rnd prepare the mailing out, but that isn't possible . for the sake of throwing of tltr or that the PTUA enjoys it. because the Newslefler is printed first. Instead, we environment. It also calls for the incorporation <;f llrr include the names of those who have assisted in He has overlooked two crucial facts: recent issues, and without whose help norre of this a Backin 1982in itsforward-lookingTronsportfortheEighties, thePTUAlaunchedoneof the would be possible most comprehensive and constuctive plans for the rehabilitation of the sadly neglected public ,lohn Alexopoulos, David Bowd, Bill Devine, Ken hansport system. Many of the proposals co-incided with the Labor Party's promises.