Obesity and Obesogenic Growth Are Both Highly Heritable and Modified by Diet in a Nonhuman Primate Model, the African Green Monk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

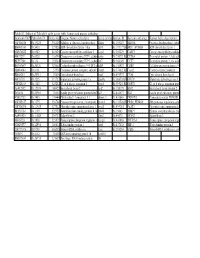

Table S3: Subset of Zebrafish Early Genes with Human And

Table S3: Subset of Zebrafish early genes with human and mouse orthologs Genbank ID(ZFZebrafish ID Entrez GenUnigene Name (zebrafish) Gene symbo Human ID Humann ortholog Human Gene description AW116838 Dr.19225 336425 Aldolase a, fructose-bisphosphate aldoa Hs.155247 ALDOA Fructose-bisphosphate aldola BM005100 Dr.5438 327026 ADP-ribosylation factor 1 like arf1l Hs.119177||HsARF1_HUMAN ADP-ribosylation factor 1 AW076882 Dr.6582 403025 Cancer susceptibility candidate 3 casc3 Hs.350229 CASC3 Cancer susceptibility candidat AI437239 Dr.6928 116994 Chaperonin containing TCP1, subun cct6a Hs.73072||Hs.CCT6A T-complex protein 1, zeta sub BE557308 Dr.134 192324 Chaperonin containing TCP1, subun cct7 Hs.368149 CCT7 T-complex protein 1, eta subu BG303647 Dr.26326 321602 Cyclin-dependent kinase 9 (CDC2-recdk9 Hs.150423 CDK9 Cell division protein kinase 9 AB040044 Dr.8161 57970 Coatomer protein complex, subunit zcopz1 Hs.37482||Hs.Copz2 Coatomer zeta-2 subunit BI888253 Dr.20911 30436 Eyes absent homolog 1 eya1 Hs.491997 EYA4 Eyes absent homolog 4 AI878758 Dr.3225 317737 Glutamate dehydrogenase 1a glud1a Hs.368538||HsGLUD1 Glutamate dehydrogenase 1, AW128619 Dr.1388 325284 G1 to S phase transition 1 gspt1 Hs.59523||Hs.GSPT1 G1 to S phase transition prote AF412832 Dr.12595 140427 Heat shock factor 2 hsf2 Hs.158195 HSF2 Heat shock factor protein 2 D38454 Dr.20916 30151 Insulin gene enhancer protein Islet3 isl3 Hs.444677 ISL2 Insulin gene enhancer protein AY052752 Dr.7485 170444 Pbx/knotted 1 homeobox 1.1 pknox1.1 Hs.431043 PKNOX1 Homeobox protein PKNOX1 -

Supplemental Information

Supplemental information Dissection of the genomic structure of the miR-183/96/182 gene. Previously, we showed that the miR-183/96/182 cluster is an intergenic miRNA cluster, located in a ~60-kb interval between the genes encoding nuclear respiratory factor-1 (Nrf1) and ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2H (Ube2h) on mouse chr6qA3.3 (1). To start to uncover the genomic structure of the miR- 183/96/182 gene, we first studied genomic features around miR-183/96/182 in the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.UCSC.edu/), and identified two CpG islands 3.4-6.5 kb 5’ of pre-miR-183, the most 5’ miRNA of the cluster (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1 and Seq. S1). A cDNA clone, AK044220, located at 3.2-4.6 kb 5’ to pre-miR-183, encompasses the second CpG island (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). We hypothesized that this cDNA clone was derived from 5’ exon(s) of the primary transcript of the miR-183/96/182 gene, as CpG islands are often associated with promoters (2). Supporting this hypothesis, multiple expressed sequences detected by gene-trap clones, including clone D016D06 (3, 4), were co-localized with the cDNA clone AK044220 (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). Clone D016D06, deposited by the German GeneTrap Consortium (GGTC) (http://tikus.gsf.de) (3, 4), was derived from insertion of a retroviral construct, rFlpROSAβgeo in 129S2 ES cells (Fig. 1A and C). The rFlpROSAβgeo construct carries a promoterless reporter gene, the β−geo cassette - an in-frame fusion of the β-galactosidase and neomycin resistance (Neor) gene (5), with a splicing acceptor (SA) immediately upstream, and a polyA signal downstream of the β−geo cassette (Fig. -

Genetic and Pharmacological Approaches to Preventing Neurodegeneration

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Genetic and Pharmacological Approaches to Preventing Neurodegeneration Marco Boccitto University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Neuroscience and Neurobiology Commons Recommended Citation Boccitto, Marco, "Genetic and Pharmacological Approaches to Preventing Neurodegeneration" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 494. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/494 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/494 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Genetic and Pharmacological Approaches to Preventing Neurodegeneration Abstract The Insulin/Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 Signaling (IIS) pathway was first identified as a major modifier of aging in C.elegans. It has since become clear that the ability of this pathway to modify aging is phylogenetically conserved. Aging is a major risk factor for a variety of neurodegenerative diseases including the motor neuron disease, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). This raises the possibility that the IIS pathway might have therapeutic potential to modify the disease progression of ALS. In a C. elegans model of ALS we found that decreased IIS had a beneficial effect on ALS pathology in this model. This beneficial effect was dependent on activation of the transcription factor daf-16. To further validate IIS as a potential therapeutic target for treatment of ALS, manipulations of IIS in mammalian cells were investigated for neuroprotective activity. Genetic manipulations that increase the activity of the mammalian ortholog of daf-16, FOXO3, were found to be neuroprotective in a series of in vitro models of ALS toxicity. -

Large-Scale Rnai Screening Uncovers New Therapeutic Targets in the Human Parasite

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.05.935833; this version posted February 6, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 Large-scale RNAi screening uncovers new therapeutic targets in the human parasite 2 Schistosoma mansoni 3 4 Jipeng Wang1*, Carlos Paz1*, Gilda Padalino2, Avril Coghlan3, Zhigang Lu3, Irina Gradinaru1, 5 Julie N.R. Collins1, Matthew Berriman3, Karl F. Hoffmann2, James J. Collins III1†. 6 7 8 1Department of Pharmacology, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas 75390 9 2Institute of Biological, Environmental and Rural Sciences (IBERS), Aberystwyth University, 10 Aberystwyth, Wales, UK. 11 3Wellcome Sanger Institute, Wellcome Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge CB10 1SA, UK 12 *Equal Contribution 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 †To whom correspondence should be addressed 24 [email protected] 25 UT Southwestern Medical Center 26 Department of Pharmacology 27 6001 Forest Park. Rd. 28 Dallas, TX 75390 29 United States of America bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.05.935833; this version posted February 6, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 30 ABSTRACT 31 Schistosomes kill 250,000 people every year and are responsible for serious morbidity in 240 32 million of the world’s poorest people. -

862F50a0ea63c82ca473bf845b5

Brain region Type Enriched GO annotation Gene symbol AQR, ARMC7, BTBD9, HACL1, KCTD10, KCTD13, LSM6, MT2A, MYBPC1, POLD2, SRPX, TNFAIP1, USP25, EC Common type DNA replication, Protein catabolic process, Transport USP28, ZMYND19 EC Common type Transport KIAA1549, MBD5, MYO5B, RAB11A, RAB11FIP1, RAB11FIP2, RAB11FIP3, RAB11FIP4, RAB11FIP5, REPS1 ACD, BMP2K, C1orf63, CDK13, CLK3, CYLC2, DDX3Y, FOXJ3, GNL3L, GRPEL1, KIAA2022, MACROD2, Cellular component organization, Kinase activity, Localization, EC Common type NANOG, PAK1IP1, PCBP1, PCMT1, PLOD1, PLOD2, POT1, PRPS1L1, RASGEF1C, RBM15B, RPS7, RSBN1L, Response to stimulus, Transcription SALL1, SEC16A, TDRD6, TERF1, TERF2IP, TINF2, YTHDF1, YTHDF3, ZC3HAV1L, ZNF281 AGFG1, AKR1C3, ARIH1, ARIH2, BCL10, BFAR, BIRC2, BIRC3, BIRC6, BIRC7, C9orf89, CADPS2, CNOT4, DDX58, DIABLO, DTX1, DTX3L, DZIP3, EIF4E2, EML4, EPS15, EXTL3, FBXL19, FCHO2, GPR108, HLTF, HPCA, HTRA2, INF2, ISG15, KIAA1107, KIAA1797, LNX2, LOC147791, LRSAM1, LTN1, MAGEL2, MAP3K1, MARCH5, MARCH7, MC1R, MFN1, MGRN1, MID1, MID2, MKRN1, MKRN2, MKRN3, MRAP, MUL1, NAIP, PARP9, PCNP, PDZRN3, PJA2, PLCD4, RBCK1, RLIM, RMND5B, RNF10, RNF103, RNF11, RNF111, RNF114, DNA repair, Apoptosis, Protein catabolic process, Protein EC Common type RNF115, RNF125, RNF126, RNF128, RNF13, RNF130, RNF138, RNF14, RNF144A, RNF150, RNF165, RNF166, metabolic process, Protein modification process RNF167, RNF181, RNF182, RNF25, RNF26, RNF38, RNF4, RNF41, RSPRY1, SGCE, SH3RF2, STRADB, TMBIM6, TMEM189, TOPORS, TRAF7, TRIM2, TRIM25, TRIM26, TRIM27, TRIM32, TRIM35, TRIM39, -

A Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Four Novel Susceptibility Loci Underlying Inguinal Hernia

UCSF UC San Francisco Previously Published Works Title A genome-wide association study identifies four novel susceptibility loci underlying inguinal hernia. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7g06z1k5 Journal Nature communications, 6(1) ISSN 2041-1723 Authors Jorgenson, Eric Makki, Nadja Shen, Ling et al. Publication Date 2015-12-21 DOI 10.1038/ncomms10130 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ARTICLE Received 24 Aug 2015 | Accepted 6 Nov 2015 | Published 21 Dec 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms10130 OPEN A genome-wide association study identifies four novel susceptibility loci underlying inguinal hernia Eric Jorgenson1,*, Nadja Makki2,3,*, Ling Shen1, David C. Chen4, Chao Tian5, Walter L. Eckalbar2,3, David Hinds5, Nadav Ahituv2,3 & Andrew Avins1 Inguinal hernia repair is one of the most commonly performed operations in the world, yet little is known about the genetic mechanisms that predispose individuals to develop inguinal hernias. We perform a genome-wide association analysis of surgically confirmed inguinal hernias in 72,805 subjects (5,295 cases and 67,510 controls) and confirm top associations in an independent cohort of 92,444 subjects with self-reported hernia repair surgeries (9,701 cases and 82,743 controls). We identify four novel inguinal hernia susceptibility loci in the regions of EFEMP1, WT1, EBF2 and ADAMTS6. Moreover, we observe expression of all four genes in mouse connective tissue and network analyses show an important role for two of these genes (EFEMP1 and WT1) in connective tissue maintenance/homoeostasis. Our findings provide insight into the aetiology of hernia development and highlight genetic pathways for studies of hernia development and its treatment. -

CCT6A Sirna (Mouse)

For research purposes only, not for human use Product Data Sheet CCT6A siRNA (Mouse) Catalog # Source Reactivity Applications CRM0566 Synthetic M RNAi Description siRNA to inhibit CCT6A expression using RNA interference Specificity CCT6A siRNA (Mouse) is a target-specific 19-23 nt siRNA oligo duplexes designed to knock down gene expression. Form Lyophilized powder Gene Symbol CCT6A Alternative Names CCT6; CCTZ; CCTZ1; T-complex protein 1 subunit zeta; TCP-1-zeta; CCT-zeta-1 Entrez Gene 12466 (Mouse) SwissProt P80317 (Mouse) Purity > 97% Quality Control Oligonucleotide synthesis is monitored base by base through trityl analysis to ensure appropriate coupling efficiency. The oligo is subsequently purified by affinity-solid phase extraction. The annealed RNA duplex is further analyzed by mass spectrometry to verify the exact composition of the duplex. Each lot is compared to the previous lot by mass spectrometry to ensure maximum lot-to-lot consistency. Components We offers pre-designed sets of 3 different target-specific siRNA oligo duplexes of mouse CCT6A gene. Each vial contains 5 nmol of lyophilized siRNA. The duplexes can be transfected individually or pooled together to achieve knockdown of the target gene, which is most commonly assessed by qPCR or western blot. Our siRNA oligos are also chemically modified (2’-OMe) at no extra charge for increased stability and enhanced knockdown in vitro and in vivo. Directions for Use We recommends transfection with 100 nM siRNA 48 to 72 hours prior to cell lysis. Application key: E- ELISA, WB- -

Overexpressing CCT6A Contributes to Cancer Cell Growth by Affecting the G1-To-S Phase Transition and Predicts a Negative Prognosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

OncoTargets and Therapy Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article ORIGINAL RESEARCH Overexpressing CCT6A Contributes To Cancer Cell Growth By Affecting The G1-To-S Phase Transition And Predicts A Negative Prognosis In Hepatocellular Carcinoma This article was published in the following Dove Press journal: OncoTargets and Therapy Guofen Zeng1,* Purpose: To determine the oncogenic role of the sixth subunit of chaperonin-containing Jialiang Wang2,* tailless complex polypeptide 1 (CCT6A) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and address the Yanlin Huang 1,* correlation of CCT6A with clinicopathological characteristics and survival. Additionally, this Yifan Lian 2 study aimed to explore the effect of CCT6A on HCC cells and the underlying mechanisms. Dongmei Chen2 Methods: We searched for levels of CCT6A expression in the Oncomine database and GEPIA database, which was then validated by analyzing cancer and adjacent non-cancerous Huan Wei 2 tissues of HCC patients using quantitative PCR, Western blot, and immunohistochemistry Chaoshuang Lin1 1,2 assays. The relationship between CCT6A expression and survival was analyzed from the Yuehua Huang GEPIA database and confirmed by immunohistochemistry assays of 133 HCC tissue sec- 1Department of Infectious Diseases, The tions. In addition, the effect of depleting CCT6A on cell proliferation was assessed by CCK- fi Third Af liated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen 8 and colony formation assays. Cell cycle analysis, immunofluorescence assays, GSEA University, Guangzhou 510630, Guangdong, People’s Republic of China; analysis, and cyclin D expression analyzed by Western blot were used to explore the possible 2Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of underlying mechanism how dysregulated CCT6A affect the proliferation of HCC. -

Open Full Page

Published OnlineFirst February 10, 2017; DOI: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1045 RESEARCH ARTICLE Interaction Landscape of Inherited Polymorphisms with Somatic Events in Cancer Hannah Carter 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , Rachel Marty 5 , Matan Hofree 6 , Andrew M. Gross 5 , James Jensen 5 , Kathleen M. Fisch1,2,3,7 , Xingyu Wu 2 , Christopher DeBoever 5 , Eric L. Van Nostrand 4,8 , Yan Song 4,8 , Emily Wheeler 4,8 , Jason F. Kreisberg 1,3 , Scott M. Lippman 2 , Gene W. Yeo 4,8 , J. Silvio Gutkind 2 , 3 , and Trey Ideker 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5,6 Downloaded from cancerdiscovery.aacrjournals.org on September 27, 2021. © 2017 American Association for Cancer Research. Published OnlineFirst February 10, 2017; DOI: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1045 ABSTRACT Recent studies have characterized the extensive somatic alterations that arise dur- ing cancer. However, the somatic evolution of a tumor may be signifi cantly affected by inherited polymorphisms carried in the germline. Here, we analyze genomic data for 5,954 tumors to reveal and systematically validate 412 genetic interactions between germline polymorphisms and major somatic events, including tumor formation in specifi c tissues and alteration of specifi c cancer genes. Among germline–somatic interactions, we found germline variants in RBFOX1 that increased incidence of SF3B1 somatic mutation by 8-fold via functional alterations in RNA splicing. Similarly, 19p13.3 variants were associated with a 4-fold increased likelihood of somatic mutations in PTEN. In support of this associ- ation, we found that PTEN knockdown sensitizes the MTOR pathway to high expression of the 19p13.3 gene GNA11 . -

The Genetics of Bipolar Disorder

Molecular Psychiatry (2008) 13, 742–771 & 2008 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 1359-4184/08 $30.00 www.nature.com/mp FEATURE REVIEW The genetics of bipolar disorder: genome ‘hot regions,’ genes, new potential candidates and future directions A Serretti and L Mandelli Institute of Psychiatry, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy Bipolar disorder (BP) is a complex disorder caused by a number of liability genes interacting with the environment. In recent years, a large number of linkage and association studies have been conducted producing an extremely large number of findings often not replicated or partially replicated. Further, results from linkage and association studies are not always easily comparable. Unfortunately, at present a comprehensive coverage of available evidence is still lacking. In the present paper, we summarized results obtained from both linkage and association studies in BP. Further, we indicated new potential interesting genes, located in genome ‘hot regions’ for BP and being expressed in the brain. We reviewed published studies on the subject till December 2007. We precisely localized regions where positive linkage has been found, by the NCBI Map viewer (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mapview/); further, we identified genes located in interesting areas and expressed in the brain, by the Entrez gene, Unigene databases (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/) and Human Protein Reference Database (http://www.hprd.org); these genes could be of interest in future investigations. The review of association studies gave interesting results, as a number of genes seem to be definitively involved in BP, such as SLC6A4, TPH2, DRD4, SLC6A3, DAOA, DTNBP1, NRG1, DISC1 and BDNF. -

The Genetic Architecture of Down Syndrome Phenotypes Revealed by High-Resolution Analysis of Human Segmental Trisomies

The genetic architecture of Down syndrome phenotypes revealed by high-resolution analysis of human segmental trisomies Jan O. Korbela,b,c,1, Tal Tirosh-Wagnerd,1, Alexander Eckehart Urbane,f,1, Xiao-Ning Chend, Maya Kasowskie, Li Daid, Fabian Grubertf, Chandra Erdmang, Michael C. Gaod, Ken Langeh,i, Eric M. Sobelh, Gillian M. Barlowd, Arthur S. Aylsworthj,k, Nancy J. Carpenterl, Robin Dawn Clarkm, Monika Y. Cohenn, Eric Dorano, Tzipora Falik-Zaccaip, Susan O. Lewinq, Ira T. Lotto, Barbara C. McGillivrayr, John B. Moeschlers, Mark J. Pettenatit, Siegfried M. Pueschelu, Kathleen W. Raoj,k,v, Lisa G. Shafferw, Mordechai Shohatx, Alexander J. Van Ripery, Dorothy Warburtonz,aa, Sherman Weissmanf, Mark B. Gersteina, Michael Snydera,e,2, and Julie R. Korenbergd,h,bb,2 Departments of aMolecular Biophysics and Biochemistry, eMolecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology, and fGenetics, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 06520; bEuropean Molecular Biology Laboratory, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany; cEuropean Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) Outstation Hinxton, EMBL-European Bioinformatics Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge CB10 1SA, United Kingdom; dMedical Genetics Institute, Cedars–Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA 90048; gDepartment of Statistics, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520; Departments of hHuman Genetics, and iBiomathematics, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095; Departments of jPediatrics and kGenetics, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599; lCenter for Genetic Testing,