Open Full Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (PDF)

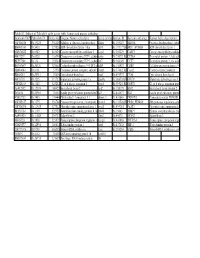

ANALYTICAL SCIENCES NOVEMBER 2020, VOL. 36 1 2020 © The Japan Society for Analytical Chemistry Supporting Information Fig. S1 Detailed MS/MS data of myoglobin. 17 2 ANALYTICAL SCIENCES NOVEMBER 2020, VOL. 36 Table S1 : The protein names (antigens) identified by pH 2.0 solution in the eluted-fraction. These proteins were identified one or more out of six analyses. Accession Description P08908 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 1A OS=Homo sapiens GN=HTR1A PE=1 SV=3 - [5HT1A_HUMAN] Q9NRR6 72 kDa inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase OS=Homo sapiens GN=INPP5E PE=1 SV=2 - [INP5E_HUMAN] P82987 ADAMTS-like protein 3 OS=Homo sapiens GN=ADAMTSL3 PE=2 SV=4 - [ATL3_HUMAN] Q9Y6K8 Adenylate kinase isoenzyme 5 OS=Homo sapiens GN=AK5 PE=1 SV=2 - [KAD5_HUMAN] P02763 Alpha-1-acid glycoprotein 1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=ORM1 PE=1 SV=1 - [A1AG1_HUMAN] P19652 Alpha-1-acid glycoprotein 2 OS=Homo sapiens GN=ORM2 PE=1 SV=2 - [A1AG2_HUMAN] P01011 Alpha-1-antichymotrypsin OS=Homo sapiens GN=SERPINA3 PE=1 SV=2 - [AACT_HUMAN] P01009 Alpha-1-antitrypsin OS=Homo sapiens GN=SERPINA1 PE=1 SV=3 - [A1AT_HUMAN] P04217 Alpha-1B-glycoprotein OS=Homo sapiens GN=A1BG PE=1 SV=4 - [A1BG_HUMAN] P08697 Alpha-2-antiplasmin OS=Homo sapiens GN=SERPINF2 PE=1 SV=3 - [A2AP_HUMAN] P02765 Alpha-2-HS-glycoprotein OS=Homo sapiens GN=AHSG PE=1 SV=1 - [FETUA_HUMAN] P01023 Alpha-2-macroglobulin OS=Homo sapiens GN=A2M PE=1 SV=3 - [A2MG_HUMAN] P01019 Angiotensinogen OS=Homo sapiens GN=AGT PE=1 SV=1 - [ANGT_HUMAN] Q9NQ90 Anoctamin-2 OS=Homo sapiens GN=ANO2 PE=1 SV=2 - [ANO2_HUMAN] P01008 Antithrombin-III -

ANP32A and ANP32B Are Key Factors in the Rev Dependent CRM1 Pathway

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/559096; this version posted February 24, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 ANP32A and ANP32B are key factors in the Rev dependent CRM1 pathway 2 for nuclear export of HIV-1 unspliced mRNA 3 Yujie Wang1, Haili Zhang1, Lei Na 1, Cheng Du1, Zhenyu Zhang1, Yong-Hui Zheng1,2, Xiaojun Wang1* 4 1State Key Laboratory of Veterinary Biotechnology, Harbin Veterinary Research Institute, the Chinese 5 Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Harbin 150069, China 6 2Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan, 7 USA. 8 * Address correspondence to Xiaojun Wang, [email protected]. 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/559096; this version posted February 24, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 22 Abstract 23 The nuclear export receptor CRM1 is an important regulator involved in the shuttling of various cellular 24 and viral RNAs between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. HIV-1 Rev interacts with CRM1 in the late phase of 25 HIV-1 replication to promote nuclear export of unspliced and single spliced HIV-1 transcripts. However, the 26 knowledge of cellular factors that are involved in the CRM1-dependent viral RNA nuclear export remains 27 inadequate. Here, we identified that ANP32A and ANP32B mediate the export of unspliced or partially spliced 28 viral mRNA via interacting with Rev and CRM1. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Table S3: Subset of Zebrafish Early Genes with Human And

Table S3: Subset of Zebrafish early genes with human and mouse orthologs Genbank ID(ZFZebrafish ID Entrez GenUnigene Name (zebrafish) Gene symbo Human ID Humann ortholog Human Gene description AW116838 Dr.19225 336425 Aldolase a, fructose-bisphosphate aldoa Hs.155247 ALDOA Fructose-bisphosphate aldola BM005100 Dr.5438 327026 ADP-ribosylation factor 1 like arf1l Hs.119177||HsARF1_HUMAN ADP-ribosylation factor 1 AW076882 Dr.6582 403025 Cancer susceptibility candidate 3 casc3 Hs.350229 CASC3 Cancer susceptibility candidat AI437239 Dr.6928 116994 Chaperonin containing TCP1, subun cct6a Hs.73072||Hs.CCT6A T-complex protein 1, zeta sub BE557308 Dr.134 192324 Chaperonin containing TCP1, subun cct7 Hs.368149 CCT7 T-complex protein 1, eta subu BG303647 Dr.26326 321602 Cyclin-dependent kinase 9 (CDC2-recdk9 Hs.150423 CDK9 Cell division protein kinase 9 AB040044 Dr.8161 57970 Coatomer protein complex, subunit zcopz1 Hs.37482||Hs.Copz2 Coatomer zeta-2 subunit BI888253 Dr.20911 30436 Eyes absent homolog 1 eya1 Hs.491997 EYA4 Eyes absent homolog 4 AI878758 Dr.3225 317737 Glutamate dehydrogenase 1a glud1a Hs.368538||HsGLUD1 Glutamate dehydrogenase 1, AW128619 Dr.1388 325284 G1 to S phase transition 1 gspt1 Hs.59523||Hs.GSPT1 G1 to S phase transition prote AF412832 Dr.12595 140427 Heat shock factor 2 hsf2 Hs.158195 HSF2 Heat shock factor protein 2 D38454 Dr.20916 30151 Insulin gene enhancer protein Islet3 isl3 Hs.444677 ISL2 Insulin gene enhancer protein AY052752 Dr.7485 170444 Pbx/knotted 1 homeobox 1.1 pknox1.1 Hs.431043 PKNOX1 Homeobox protein PKNOX1 -

CTNS Molecular Genetics Profile in a Persian Nephropathic Cystinosis Population

n e f r o l o g i a 2 0 1 7;3 7(3):301–310 Revista de la Sociedad Española de Nefrología www.revistanefrologia.com Original article CTNS molecular genetics profile in a Persian nephropathic cystinosis population a b a a Farideh Ghazi , Rozita Hosseini , Mansoureh Akouchekian , Shahram Teimourian , a b c,d a,b,c,d,∗ Zohreh Ataei Kachoei , Hassan Otukesh , William A. Gahl , Babak Behnam a Department of Medical Genetics and Molecular Biology, Faculty of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences (IUMS), Tehran, Iran b Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Ali Asghar Children Hospital, Iran University of Medical Sciences (IUMS), Tehran, Iran c Section on Human Biochemical Genetics, Medical Genetics Branch, National Human Genome Research Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA d NIH Undiagnosed Diseases Program, Common Fund, Office of the Director, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Purpose: In this report, we document the CTNS gene mutations of 28 Iranian patients with Received 26 May 2016 nephropathic cystinosis age 1–17 years. All presented initially with severe failure to thrive, Accepted 22 November 2016 polyuria, and polydipsia. Available online 24 February 2017 Methods: Cystinosis was primarily diagnosed by a pediatric nephrologist and then referred to the Iran University of Medical Sciences genetics clinic for consultation and molecular Keywords: analysis, which involved polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification to determine the Cystinosis presence or absence of the 57-kb founder deletion in CTNS, followed by direct sequencing CTNS of the coding exons of CTNS. -

Supplemental Material Placed on This Supplemental Material Which Has Been Supplied by the Author(S) J Med Genet

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) J Med Genet Supplement Supplementary Table S1: GENE MEAN GENE NAME OMIM SYMBOL COVERAGE CAKUT CAKUT ADTKD ADTKD aHUS/TMA aHUS/TMA TUBULOPATHIES TUBULOPATHIES Glomerulopathies Glomerulopathies Polycystic kidneys / Ciliopathies Ciliopathies / kidneys Polycystic METABOLIC DISORDERS AND OTHERS OTHERS AND DISORDERS METABOLIC x x ACE angiotensin-I converting enzyme 106180 139 x ACTN4 actinin-4 604638 119 x ADAMTS13 von Willebrand cleaving protease 604134 154 x ADCY10 adenylate cyclase 10 605205 81 x x AGT angiotensinogen 106150 157 x x AGTR1 angiotensin II receptor, type 1 106165 131 x AGXT alanine-glyoxylate aminotransferase 604285 173 x AHI1 Abelson helper integration site 1 608894 100 x ALG13 asparagine-linked glycosylation 13 300776 232 x x ALG9 alpha-1,2-mannosyltransferase 606941 165 centrosome and basal body associated x ALMS1 606844 132 protein 1 x x APOA1 apolipoprotein A-1 107680 55 x APOE lipoprotein glomerulopathy 107741 77 x APOL1 apolipoprotein L-1 603743 98 x x APRT adenine phosphoribosyltransferase 102600 165 x ARHGAP24 Rho GTPase-Activation protein 24 610586 215 x ARL13B ADP-ribosylation factor-like 13B 608922 195 x x ARL6 ADP-ribosylation factor-like 6 608845 215 ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal V0, x ATP6V0A4 605239 90 subunit a4 ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal x x ATP6V1B1 192132 163 56/58, V1, subunit B1 x ATXN10 ataxin -

Supplemental Information

Supplemental information Dissection of the genomic structure of the miR-183/96/182 gene. Previously, we showed that the miR-183/96/182 cluster is an intergenic miRNA cluster, located in a ~60-kb interval between the genes encoding nuclear respiratory factor-1 (Nrf1) and ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2H (Ube2h) on mouse chr6qA3.3 (1). To start to uncover the genomic structure of the miR- 183/96/182 gene, we first studied genomic features around miR-183/96/182 in the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.UCSC.edu/), and identified two CpG islands 3.4-6.5 kb 5’ of pre-miR-183, the most 5’ miRNA of the cluster (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1 and Seq. S1). A cDNA clone, AK044220, located at 3.2-4.6 kb 5’ to pre-miR-183, encompasses the second CpG island (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). We hypothesized that this cDNA clone was derived from 5’ exon(s) of the primary transcript of the miR-183/96/182 gene, as CpG islands are often associated with promoters (2). Supporting this hypothesis, multiple expressed sequences detected by gene-trap clones, including clone D016D06 (3, 4), were co-localized with the cDNA clone AK044220 (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). Clone D016D06, deposited by the German GeneTrap Consortium (GGTC) (http://tikus.gsf.de) (3, 4), was derived from insertion of a retroviral construct, rFlpROSAβgeo in 129S2 ES cells (Fig. 1A and C). The rFlpROSAβgeo construct carries a promoterless reporter gene, the β−geo cassette - an in-frame fusion of the β-galactosidase and neomycin resistance (Neor) gene (5), with a splicing acceptor (SA) immediately upstream, and a polyA signal downstream of the β−geo cassette (Fig. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Towards an Understanding of Inflammation in Macrophages a Dissertation Submitted in Partial

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Towards an Understanding of Inflammation in Macrophages A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Sciences by Dawn Xiaobin Zhang Committee in charge: Professor Christopher L. Glass, Chair Professor Jack Bui Professor Ronald M. Evans Professor Richard L. Gallo Professor Joseph L. Witztum 2014 Copyright Dawn Xiaobin Zhang, 2014 All rights reserved. This Dissertation of Dawn Xiaobin Zhang is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii DEDICATION To my family and the love of my life, Matthew. iv EPIGRAPH How often have I said to you that when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth? -Sherlock Holmes, From The Sign of the Four, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ……………………………………………………………….. iii Dedication ……………………………………………………….…………….. iv Epigraph ……………………………………………………………………….. v Table of Contents ………………………………………………………….….. vi List of Figures ………………………………………………………….………. viii List of Tables ………………………………………………………….…….…. x Acknowledgements …………………………………….…………………..…. xi Vita …………………………………….……………………………………..…. xiii Abstract of the Dissertation ………………………………..…………………. xv Chapter I: Introduction: Towards an Understanding of Cell-Specific Function of Signal-Dependent Transcription Factors ……....…....…... 1 A. Abstract ……....…....………………………………...…………….. 2 B. Introduction -

GENOME EDITING in AFRICA’S AGRICULTURE 2021 an EARLY TAKE-OFF TABLE of CONTENTS Abbreviations and Acronyms 3

GENOME EDITING IN AFRICA’S AGRICULTURE 2021 AN EARLY TAKE-OFF TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations and Acronyms 3 1. Introduction 4 1.1 Milestones in Plant Breeding 5 1.2 How CRISPR genome editing works in agriculture 6 2 . Genome editing projects and experts in eastern Africa 7 2.1 Kenya 8 2.2 Ethiopia 14 2.3 Uganda 15 3 . Gene editing projects and experts in southern Africa 17 3.1 South Africa 18 4. Gene editing projects and experts in West Africa 19 4.1 Nigeria 20 5. Gene editing projects and experts in Central Africa 21 5.1 Cameroon 22 6. Gene editing projects and experts in North Africa 23 6.1 Egypt 24 7. Conclusion 25 8. CRISPR genome editing: inside a crop breeder’s toolkit 26 9. Regulatory Approaches for Genome Edited Products in Various Countries 27 10. Communicating about Genome Editing in Africa 28 2 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS CRISPR Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats DNA Deoxyribonucleic acid GM Genetically Modified GMO Genetically Modified Organism HDR Homology Directed Repair ISAAA International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications NHEJ Non Homologous End Joining PCR Polymerase Chain Reaction RNA Ribonucleic Acid LGS1 Low germination stimulant 1 3 1.0 INTRODUCTION Genome editing (also referred to as gene editing) comprises a arm is provided with the CRISPR-Cas9 cassette, homology-directed group of technologies that give scientists the ability to change an repair (HDR) will occur, otherwise the cell will employ non- organism’s DNA. These technologies allow addition, removal or homologous end joining (NHEJ) to create small indels at the cut site alteration of genetic material at particular locations in the genome. -

CTNS Gene Cystinosin, Lysosomal Cystine Transporter

CTNS gene cystinosin, lysosomal cystine transporter Normal Function The CTNS gene provides instructions for making a protein called cystinosin. This protein is located in the membrane of lysosomes, which are compartments in the cell that digest and recycle materials. Proteins digested inside lysosomes are broken down into smaller building blocks, called amino acids. The amino acids are then moved out of lysosomes by transport proteins. Cystinosin is a transport protein that specifically moves the amino acid cystine out of the lysosome. Health Conditions Related to Genetic Changes Cystinosis More than 80 different mutations that are responsible for causing cystinosis have been identified in the CTNS gene. The most common mutation is a deletion of a large part of the CTNS gene (sometimes referred to as the 57-kb deletion), resulting in the complete loss of cystinosin. This deletion is responsible for approximately 50 percent of cystinosis cases in people of European descent. Other mutations result in the production of an abnormally short protein that cannot carry out its normal transport function. Mutations that change very small regions of the CTNS gene may allow the transporter protein to retain some of its usual activity, resulting in a milder form of cystinosis. Other Names for This Gene • CTNS-LSB • CTNS_HUMAN • Cystinosis • PQLC4 Additional Information & Resources Tests Listed in the Genetic Testing Registry • Tests of CTNS (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gtr/all/tests/?term=1497[geneid]) Reprinted from MedlinePlus Genetics (https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/) 1 Scientific Articles on PubMed • PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=%28CTNS%5BTIAB%5D%29+O R+%28Cystinosis%5BTIAB%5D%29+AND+%28Genes%5BMH%5D%29+AND+eng lish%5Bla%5D+AND+human%5Bmh%5D+AND+%22last+3600+days%22%5Bdp% 5D) Catalog of Genes and Diseases from OMIM • CYSTINOSIN (https://omim.org/entry/606272) Research Resources • ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar?term=CTNS[gene]) • NCBI Gene (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/1497) References • Anikster Y, Shotelersuk V, Gahl WA. -

CCT6A Sirna (Mouse)

For research purposes only, not for human use Product Data Sheet CCT6A siRNA (Mouse) Catalog # Source Reactivity Applications CRM0566 Synthetic M RNAi Description siRNA to inhibit CCT6A expression using RNA interference Specificity CCT6A siRNA (Mouse) is a target-specific 19-23 nt siRNA oligo duplexes designed to knock down gene expression. Form Lyophilized powder Gene Symbol CCT6A Alternative Names CCT6; CCTZ; CCTZ1; T-complex protein 1 subunit zeta; TCP-1-zeta; CCT-zeta-1 Entrez Gene 12466 (Mouse) SwissProt P80317 (Mouse) Purity > 97% Quality Control Oligonucleotide synthesis is monitored base by base through trityl analysis to ensure appropriate coupling efficiency. The oligo is subsequently purified by affinity-solid phase extraction. The annealed RNA duplex is further analyzed by mass spectrometry to verify the exact composition of the duplex. Each lot is compared to the previous lot by mass spectrometry to ensure maximum lot-to-lot consistency. Components We offers pre-designed sets of 3 different target-specific siRNA oligo duplexes of mouse CCT6A gene. Each vial contains 5 nmol of lyophilized siRNA. The duplexes can be transfected individually or pooled together to achieve knockdown of the target gene, which is most commonly assessed by qPCR or western blot. Our siRNA oligos are also chemically modified (2’-OMe) at no extra charge for increased stability and enhanced knockdown in vitro and in vivo. Directions for Use We recommends transfection with 100 nM siRNA 48 to 72 hours prior to cell lysis. Application key: E- ELISA, WB- -

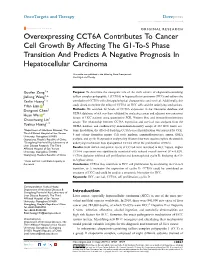

Overexpressing CCT6A Contributes to Cancer Cell Growth by Affecting the G1-To-S Phase Transition and Predicts a Negative Prognosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

OncoTargets and Therapy Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article ORIGINAL RESEARCH Overexpressing CCT6A Contributes To Cancer Cell Growth By Affecting The G1-To-S Phase Transition And Predicts A Negative Prognosis In Hepatocellular Carcinoma This article was published in the following Dove Press journal: OncoTargets and Therapy Guofen Zeng1,* Purpose: To determine the oncogenic role of the sixth subunit of chaperonin-containing Jialiang Wang2,* tailless complex polypeptide 1 (CCT6A) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and address the Yanlin Huang 1,* correlation of CCT6A with clinicopathological characteristics and survival. Additionally, this Yifan Lian 2 study aimed to explore the effect of CCT6A on HCC cells and the underlying mechanisms. Dongmei Chen2 Methods: We searched for levels of CCT6A expression in the Oncomine database and GEPIA database, which was then validated by analyzing cancer and adjacent non-cancerous Huan Wei 2 tissues of HCC patients using quantitative PCR, Western blot, and immunohistochemistry Chaoshuang Lin1 1,2 assays. The relationship between CCT6A expression and survival was analyzed from the Yuehua Huang GEPIA database and confirmed by immunohistochemistry assays of 133 HCC tissue sec- 1Department of Infectious Diseases, The tions. In addition, the effect of depleting CCT6A on cell proliferation was assessed by CCK- fi Third Af liated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen 8 and colony formation assays. Cell cycle analysis, immunofluorescence assays, GSEA University, Guangzhou 510630, Guangdong, People’s Republic of China; analysis, and cyclin D expression analyzed by Western blot were used to explore the possible 2Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of underlying mechanism how dysregulated CCT6A affect the proliferation of HCC.