Part 2--Of Pride and Envy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pilgrim's Pride Corporation; Rule 14A-8 No-Action Letter

WHITE 6. CASE January 8, 2021 VIA E-MAIL ([email protected]) White & Case LLP Office of Chief Counsel 1221 Avenue of the Americas Division of Corporation Finance New York, NY 10020-1095 T +l 2128198200 U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 100 F Street, NE whitecase.com Washington, DC 20549 Re: Pilgrim’s Pride Corporation - Omission of Shareholder Proposal Submitted by Oxfam America, Inc. Ladies and Gentlemen: On behalf of our client, Pilgrim’s Pride Corporation, a Delaware corporation (the “Company” or “PPC”), we hereby respectfully request confirmation that the staff (the “Staff”) of the Division of Corporation Finance of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (the “SEC”) will not recommend any enforcement action if, in reliance on Rule 14a-8 under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended (“Rule 14a-8”), the Company omits from its proxy statement and form of proxy for the 2021 annual meeting of its shareholders (the “2021 Proxy Materials”) the shareholder proposal and supporting statement attached hereto as Exhibit A (the “Proposal”) submitted by Oxfam America Inc. (the “Proponent”). Copies of correspondence with the Proponents regarding the Proposal are attached hereto as Exhibit B. The Company has not received any other correspondence relating to the Proposal. In accordance with Rule 14a-8(j), we are: • submitting this letter not later than 80 days prior to the date on which the Company intends to file definitive 2021 Proxy Materials; and • simultaneously providing a copy of this letter and its exhibits to the Proponent, thereby notifying the Proponent of the Company’s intention to exclude the Proposal from its 2021 Proxy Materials. -

2-22- the Four Last Things

St. Mark Seeker’s Study Guide February 22, 2017: The Four Last Things – Death, Judgment, Heaven and Hell The Four Last Things, death, judgment, heaven and hell, are realities of human life. Although our end in this world is not the most attractive topic of conversation, Christians should understand that death is a passage to new life. The Communion of the Saints is the unity of baptized Christians with all who have gone before us in the oneness of God. As Christians, we don’t just prepare for death, but we live that new life today in the sanctifying grace of our God. As we consider the Four Last things, we should do so in the context of faith. Death The Christian Life and Death: The dying should be given attention and care to help them live their last moments in dignity and peace. Assisted suicide or euthanasia are not a morally responsible use of life. The dying should be accompanied and supported. No one ought to feel that they are a burden to others. Part of the challenge of the spiritual life is to both learn to love and to be loved. Why is it harder to be loved? Prayer for the Dying: The dying will be helped by the prayer of their relatives, who must see to it that the sick receive at the proper time the Sacraments that prepare them to meet the living God” (CCC, no. 2299). Death: The final article of the Creed proclaims our belief in everlasting life. At the Catholic Rite of Commendation of the Dying, sometimes prayed at the Anointing of the Sick, we sometimes hear this prayer: “Go forth, Christian soul, from this world... -

Part 1--The Remembrance of Death

Part 1--The Remembrance of Death Part 1--The Remembrance of Death A TREATISE (UNFINISHED) UPON THESE WORDS OF HOLY SCRIPTURE Memorare novissima, & in aeternum non peccabis “Remember the last things, & thou shalt never sin.”—Ecclus. 7 . Made about the year of our Lord 1522, by Sir Thomas More then knight, and one of the Privy Council of King Henry VIII, and also Under-Treasurer of England. If there were any question among men whether the words of holy Scripture or the doctrine of any secular author were of greater force and effect to the weal and profit of man’s soul (though we should let pass so many short and weighty words spoken by the mouth of our Saviour Christ Himself, to Whose heavenly wisdom the wit of none earthly creature can be comparable) yet this only text written by the wise man in the seventh chapter of Ecclesiasticus is such that it containeth more fruitful advice and counsel to the forming and framing of man’s manners in virtue and avoiding of sin, than many whole and great volumes of the best of old philosophers or any other that ever wrote in secular literature. Long would it be to take the best of their words and compare it with these words of holy Writ. Let us consider the fruit and profit of this in itself: which thing, well advised and pondered, shall well declare that of none whole volume of secular literature shall arise so very fruitful doctrine. For what would a man give for a sure medicine that were of such strength that it should all his life keep him from sickness, namely 1 if he might by the avoiding of sickness be sure to continue his life one hundred years? So is it now that these words giveth us all a sure medicine (if we forsloth 2 not the receiving) by which we shall keep from sickness, not the body, which none health may long keep from death (for die we must in few years, live we never so long), but the soul, which here preserved from the sickness of sin, shall after this eternally live in joy and be preserved from the deadly life of everlasting pain. -

About Emotions There Are 8 Primary Emotions. You Are Born with These

About Emotions There are 8 primary emotions. You are born with these emotions wired into your brain. That wiring causes your body to react in certain ways and for you to have certain urges when the emotion arises. Here is a list of primary emotions: Eight Primary Emotions Anger: fury, outrage, wrath, irritability, hostility, resentment and violence. Sadness: grief, sorrow, gloom, melancholy, despair, loneliness, and depression. Fear: anxiety, apprehension, nervousness, dread, fright, and panic. Joy: enjoyment, happiness, relief, bliss, delight, pride, thrill, and ecstasy. Interest: acceptance, friendliness, trust, kindness, affection, love, and devotion. Surprise: shock, astonishment, amazement, astound, and wonder. Disgust: contempt, disdain, scorn, aversion, distaste, and revulsion. Shame: guilt, embarrassment, chagrin, remorse, regret, and contrition. All other emotions are made up by combining these basic 8 emotions. Sometimes we have secondary emotions, an emotional reaction to an emotion. We learn these. Some examples of these are: o Feeling shame when you get angry. o Feeling angry when you have a shame response (e.g., hurt feelings). o Feeling fear when you get angry (maybe you’ve been punished for anger). There are many more. These are NOT wired into our bodies and brains, but are learned from our families, our culture, and others. When you have a secondary emotion, the key is to figure out what the primary emotion, the feeling at the root of your reaction is, so that you can take an action that is most helpful. . -

The Evolution of the Seven Deadly Sins: from God to the Simpsons

96 Journal of Popular Culture sin. A lot. As early Christian doctrine repeatedly points out, the seven deadly sins are so deeply rooted in our fallen human nature, that not only are they almost completely unavoidable, but like a proverbial bag of The Evolution of the Seven Deadly Sins: potato chips, we can never seem to limit ourselves to just one. With this ideology, modern society agrees. However, with regard to the individual From God to the Simpsons and social effects of the consequences of these sins, we do not. The deadly sins of seven were identified, revised, and revised again Lisa Frank in the heads and classrooms of reportedly celibate monks as moral and philosophical lessons taught in an effort to arm men and women against I can personally attest that the seven deadly sins are still very much the temptations of sin and vice in the battle for their souls. These teach- with us. Today, I have committed each of them, several more than once, ings were quickly reflected in the literature, theater, art, and music of before my lunch hour even began. Here is my schedule of sin (judge me that time and throughout the centuries to follow. Today, they remain pop- if you will): ular motifs in those media, as well as having made the natural progres- sion into film and television. Every day and every hour, acts of gluttony, 7:00 - I pressed the snooze button three times before dragging myself out of lust, covetousness, envy, pride, wrath, and sloth are portrayed on televi- bed. -

Emotion Classification Based on Biophysical Signals and Machine Learning Techniques

S S symmetry Article Emotion Classification Based on Biophysical Signals and Machine Learning Techniques Oana Bălan 1,* , Gabriela Moise 2 , Livia Petrescu 3 , Alin Moldoveanu 1 , Marius Leordeanu 1 and Florica Moldoveanu 1 1 Faculty of Automatic Control and Computers, University POLITEHNICA of Bucharest, Bucharest 060042, Romania; [email protected] (A.M.); [email protected] (M.L.); fl[email protected] (F.M.) 2 Department of Computer Science, Information Technology, Mathematics and Physics (ITIMF), Petroleum-Gas University of Ploiesti, Ploiesti 100680, Romania; [email protected] 3 Faculty of Biology, University of Bucharest, Bucharest 030014, Romania; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +40722276571 Received: 12 November 2019; Accepted: 18 December 2019; Published: 20 December 2019 Abstract: Emotions constitute an indispensable component of our everyday life. They consist of conscious mental reactions towards objects or situations and are associated with various physiological, behavioral, and cognitive changes. In this paper, we propose a comparative analysis between different machine learning and deep learning techniques, with and without feature selection, for binarily classifying the six basic emotions, namely anger, disgust, fear, joy, sadness, and surprise, into two symmetrical categorical classes (emotion and no emotion), using the physiological recordings and subjective ratings of valence, arousal, and dominance from the DEAP (Dataset for Emotion Analysis using EEG, Physiological and Video Signals) database. The results showed that the maximum classification accuracies for each emotion were: anger: 98.02%, joy:100%, surprise: 96%, disgust: 95%, fear: 90.75%, and sadness: 90.08%. In the case of four emotions (anger, disgust, fear, and sadness), the classification accuracies were higher without feature selection. -

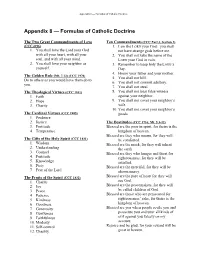

Appendix 8 — Formulas of Catholic Doctrine

Appendix 8 — Formulas of Catholic Doctrine Appendix 8 — Formulas of Catholic Doctrine The Two Great Commandments of Love Ten Commandments (CCC Part 3, Section 2) (CCC 2196) 1. I am the LORD your God: you shall 1. You shall love the Lord your God not have strange gods before me. with all your heart, with all your 2. You shall not take the name of the soul, and with all your mind. LORD your God in vain. 2. You shall love your neighbor as 3. Remember to keep holy the LORD’s yourself. Day. 4. Honor your father and your mother. The Golden Rule (Mt. 7:12) (CCC 1970) 5. You shall not kill. Do to others as you would have them do to 6. You shall not commit adultery. you. 7. You shall not steal. The Theological Virtues (CCC 1841) 8. You shall not bear false witness 1. Faith against your neighbor. 2. Hope 9. You shall not covet your neighbor’s 3. Charity wife. 10. You shall not covet your neighbor’s The Cardinal Virtues (CCC 1805) goods. 1. Prudence 2. Justice The Beatitudes (CCC 1716; Mt. 5:3-12) 3. Fortitude Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the 4. Temperance kingdom of heaven. Blessed are they who mourn, for they will The Gifts of the Holy Spirit (CCC 1831) be comforted. 1. Wisdom Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit 2. Understanding the earth. 3. Counsel Blessed are they who hunger and thirst for 4. Fortitude righteousness, for they will be 5. Knowledge satisfied. -

Pleasures of Gluttony Los Placeres De La Codicia Os Prazeres Da Gula

Pleasures of Gluttony Los placeres de la Codicia Os prazeres da Gula Burçin EROL 1 Abstract: In the late Middle Ages, especially in England, displaying an abundance of food and feasting became not only an act of pleasure but also a means of establishing status and wealth, despite gluttony being one of the seven deadly sins. In the fourteenth century – due to various reasons such as increased population, crop failure, the Black Death, and the disruption of food production by warfare – feasting, the displaying of food, and indulgence in gluttony was an indicator of wealth, riches, and high status for the upper class or the social climber as it is well indicated in the works of Chaucer and some of his contemporaries. Resumo: Especialmente na Idade Média Tardia, na Inglaterra, demonstrações de comida abundante e ceias se tornaram não somente um prazer, mas uma representação do estabelecimento de status e riqueza, apesar da gula ser proclamada um dos sete pecados capitais. No século XIV, devido a várias calamidades, como crescimento populacional, problemas na colheita , a peste negra e a quebra da produção de comida, o fornecimento e a ostentação de comida e indulgencia na gula foi um indicador de riqueza grande status para a classe alta ou para ascendentes sociais, como bem indicada nos trabalhos de Chaucer e alguns de seus contemporâneos. Keywords: Seven Deadly Sins – Gluttony – Pleasure – Middle English Literature. Palavras-chaves: Sete Pecados Capitais – Gula – Prazer – Literatura em Inglês Médio. 1 Prof. Dr., Department of English Language and Literature, Faculty of Letters, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey. E-mail: [email protected] . -

Stylish Design and Premium Performance®

Power Chairs Power Chairs Owner’s Manual Power Chairs Power Chairs Power Chairs Power Chairs Power Chairs Power Chairs Stylish Design and Premium Performance Power Chairs Exeter, PA ® St Catharines, ON 1-800-800-8586 wwwpridemobilitycom SAFETY GUIDELINES Please read and follow all instructions in this owners manual before attempting to operate your power chair for the first time If there is anything in this manual you do not understand, or if you require additional assistance for set-up, contact your authorized Pride provider Using your Pride product safely depends upon your diligence in following the warnings, cautions, and instructions in this owners manual Using your Pride product safely also depends upon your own good judgement and/or common sense, as well as that of your provider, caregiver, and/or healthcare professional Pride is not responsible for injuries and/or damage resulting from any persons failure to follow the warnings, cautions, and instructions in this owners manual Pride is not responsible for injuries and/or damage resulting from any persons failure to exercise good judgement and/or common sense The symbols below are used throughout this owners manual to identify warnings and cautions It is very important for you to read and understand them completely WARNING! Failure to heed the warnings in this owners manual may result in personal injury CAUTION! Failure to heed the cautions in this owners manual may result in damage to your power chair Copyright © 2003 Pride Mobility Products Corp INFMANU1588 CONTENTS I INTRODUCTION -

The Four Last Things Reflections on Death, Judgment, Heaven & Hell

THEOLOGY The Four Last Things Reflections on Death, Judgment, Heaven & Hell Regis Martin, S.T.D. LECTURE GUIDE Learn More www.CatholicCourses.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Lecture Summaries LECTURE 1 Introducing the Study of the Last Things.......................................................................4 LECTURE 2 The Christian Conception of Time and Its Relation to the Last Things...8 Feature: The Sacrament of the Present Moment...............................................................12 LECTURE 3 Exploring the Nature and Dynamism of Hope.......................................................14 LECTURE 4 On First Opening the Door of Death..............................................................................18 Feature: The Last Rites.......................................................................................................................22 LECTURE 5 On Seeing Death as a Christian and the Consolation It Brings............... 24 LECTURE 6 The Jig Is Up: On Judgment and the World to Come.........................................28 Feature: Purgatory................................................................................................................................ 32 LECTURE 7 On Going to Hell..............................................................................................................................34 LECTURE 8 On the Reality and Nature of Heaven.............................................................................38 Suggested Reading from Regis Martin, S.T.D.................................................................42 -

Flags and Symbols � � � Gilbert Baker Designed the Rainbow flag for the 1978 San Francisco’S Gay Freedom Celebration

Flags and Symbols ! ! ! Gilbert Baker designed the rainbow flag for the 1978 San Francisco’s Gay Freedom Celebration. In the original eight-color version, pink stood for sexuality, red for life, orange for healing, yellow for the sun, green for nature, turquoise for art, indigo for harmony and violet for the soul.! " Rainbow Flag First unveiled on 12/5/98 the bisexual pride flag was designed by Michael Page. This rectangular flag consists of a broad magenta stripe at the top (representing same-gender attraction,) a broad stripe in blue at the bottoms (representing opposite- gender attractions), and a narrower deep lavender " band occupying the central fifth (which represents Bisexual Flag attraction toward both genders). The pansexual pride flag holds the colors pink, yellow and blue. The pink band symbolizes women, the blue men, and the yellow those of a non-binary gender, such as a gender bigender or gender fluid Pansexual Flag In August, 2010, after a process of getting the word out beyond the Asexual Visibility and Education Network (AVEN) and to non-English speaking areas, a flag was chosen following a vote. The black stripe represents asexuality, the grey stripe the grey-are between sexual and asexual, the white " stripe sexuality, and the purple stripe community. Asexual Flag The Transgender Pride flag was designed by Monica Helms. It was first shown at a pride parade in Phoenix, Arizona, USA in 2000. The flag represents the transgender community and consists of five horizontal stripes. Two light blue which is the traditional color for baby boys, two pink " for girls, with a white stripe in the center for those Transgender Flag who are transitioning, who feel they have a neutral gender or no gender, and those who are intersex. -

MISERICORDES SICUT PATER” the Day I Received My First AARP Mailing, I Knew That I Had Turned a Corner

THE FOUR LAST THINGS II: “MISERICORDES SICUT PATER” The day I received my first AARP mailing, I knew that I had turned a corner. When a dear friend remarked out of the blue– “You realize, don’t you, that you have more years behind you than you have ahead of you on this earth?” Yes, I can do the math, and have known that for some time! I then recalled one of the first pieces that I learned on my saxophone at age 10 was “Nearer my God to Thee.” I’d play it accompanied by my great aunt on the piano! Yes, no matter what, we will all face the judgment seat of Christ, just as Saint Paul recounts to the Corinthians, “For we must all appear before the judgment seat of Christ, so that each one may receive good or evil, according to what he has done in the body.” Whether or not that kernel from Scripture is good news is entirely up to us. Do you ever stop to think about this reality? Do you consider judgment day? As the Year of Mercy draws to a close today, it may seem counterintuitive to discuss judgment. But in truth, judgment is not at all in conflict with the Year of Mercy theme, “Merciful as the Father,” because God’s mercy figures prominently in our judgment. So too does His Justice. We’d be delusional to think that our actions in this life ought to be free from scrutiny. I have watched the pundits break down the recent election in excruciating detail, highlighting each candidate’s campaign miscalculations and merits.