Eye and Dunsden (Apr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 2019 CTA Leads & Friends

Other projects operating in Primary Local Secondary Local Primary Secondary the CTA (e.g. BBOWT Living Conservation Target Area (CTA) CTA Lead Organisation Friends of CTA* Local Group AONB Catchment Host Authority District Authority Districts Catchment Catchment Landscape, RSPB Futurescape, etc) Str afield Br ak e, St Mar y 's Fields , Par k hill R ec Lower Cherwell Valley Kate Prudden Cherwell Cherwell BBOWT BBOWT Liv ing Lands c ape Ground Copse, Thrupp Woodland. Merton Community Wood, Wendlebury Otmoor Charlotte Kinnear RSPB David Wilding (RSPB Otmoor) Cherwell Cherwell BBOWT Ray Woodland Project. Deddington Parish Naturalists, Friends of Upper Cherwell Valley Banbury Ornithological Society Daedas Wood, Kwacs, Otter Group, Tackley Cherwell Cherwell BBOWT Heath. Oxford Heights East Martyn Lane BBOWT Sydlings Copse, Wild At Heart South Ox for ds hir e Thame RTCT Hurst Water Meadows Trust, Dorchester Thames Clifton to Shillingford Tim Read South Ox for ds hir e Thame RTCT Ock Churchyard Group, Chris Parker Ear th Tr us t Br ightw ell c um Sotw ell Env Gr oup, Abingdon Thames Radley to Abingdon Vale of White H or s e South Ox for ds hir e Ock FHT Naturalists, Abingdon GG. Rachel Sanderson (Oxford Preservation Trust), Judy Webb Vale of White Horse, Oxford Meadows and Farmoor Cherwell Ock FHT Windrush RSPB Lapwing Landscapes (Friends of Lye Valley), Thames Oxford City Water Farmoor, Catriona Bass St Giles Churchyard Conservation Group, Iffley Fields Conservation Group, Boundary Brook Nature Reserve (inc Astons Eyot), Barracks Julian Cooper (Oxford City Lane Community Garden, Oxford Meadows Thames and Cherwell at Oxford Vale of White H or s e Oxford City Ock FHT Cherwell delivery) Cons Group, New Marston Wildlife Group, SS Mary and John JWS, Friends of Trap Grounds, East Ward Allotment Ass, Hinksey Meadows JWS, Oxford Conservation Volunteers. -

Distinguished Prisoner Notes and Queries John Edmonds Th Pearson’S More Suitable Pulpit of 1852 Our Late President Occasionally Contributed to Our 18 Century

»Bridge Ends Distinguished prisoner Notes and queries John Edmonds th Pearson’s more suitable pulpit of 1852 Our late President occasionally contributed to our 18 century. In 1806 two unmarried ladies, Newsletter with topical or historical articles. His Miss Matilda and Miss Frances Rich, lived pieces demonstrate the range of his interests and the depth of his love for our villages. Reprinted there. Being the cousin and daughter of Sir here, particularly for the benefit of newer mem- Thomas Rich, retired Admiral, may explain bers of the Society, is his article from Issue 5 on the suitability of The Grove. The arrange- Admiral Villeneuve, who after his defeat by Nelson in 1805 was paroled in Sonning. ment appears to have been approved by Henry Addington, Prime Minister 1801-04, • Winter 2015 45 Issue The bicentenary of Nelson’s victory at later Viscount Sidmouth, who lived briefly Newsletter of the Sonning & Sonning Eye Society Trafalgar has a particular significance at Woodley Park. for Sonning. The defeated French The naval tradition of treating defeated Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Pierre de Vil- opponents with respect was warmly »Eye on Sonning leneuve, was billeted here for four months, upheld for Villeneuve, who never concealed Hocus-pocus in the pulpit “on parole”, having given his word that he his low opinion of Napoleon. Apparently at Diana Coulter a view from the Bridge would not try to escape. He resided at The his own request Villeneuve was permitted Probably the most reviled Archbishop ing nicknames, such as “The shrimp”, Mike Hart, Chairman Grove in Pearson Road to attend Nelson’s of Canterbury in English history was a “The little urchin” and “The little med- The Remembrance Service has just taken (formerly Sonning funeral in London. -

Cholsey and Caversham: Impacts on Protected Landscapes

Oxfordshire County Council Strategic Landscape Assessment of potential minerals working at Cholsey and Caversham: impacts on Protected Landscapes. February 2012 Oxfordshire Minerals and Waste LDF Landscape Study Contents 1 Aims and scope Background 1 Aims 1 Sites & scope 1 2 Methodology 2 Overview of Methodology 2 Assessment of landscape capacity 3 3 Policy Context 7 National Landscape Policy and Legislation 7 Regional policies 9 Oxfordshire policies 9 4 AONB plans and policies 11 Development affecting the setting of AONBs 11 Chilterns AONB policies and guidance 11 North Wessex Downs AONB policies and guidance 13 5 Cholsey 14 6 Caversham 24 7 Overall recommendations 33 Appendix 1: GIS datasets 34 Appendix 2:National Planning Policy Framework relating to 35 landscape and AONBs Appendix 2: Regional planning policies relating to landscape 37 Oxfordshire Minerals and Waste LDF Landscape Study Section 1. Aims and Scope Background 1.1 Oxfordshire’s draft Minerals and Waste Core Strategy was published for public consultation in September 2011. A concern was identified in the responses made by the Chilterns Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) and North Wessex Downs AONB. This related to potential landscape impacts on the Protected Landscapes of minerals developments within two proposed broad areas for sand and gravel working at Cholsey and Caversham. This study identifies the nature of these impacts, and potential mitigation measures which could help reduce the impacts. 1.2 The impacts identified will refer both to the operational phase of any development, and restoration phases. Recommendations may help to identify potential restoration priorities, and mitigation measures. Aims 1.3 The aim of the study is to carry out an assessment of the potential landscape impacts of minerals development within two proposed areas for mineral working on the setting of Oxfordshire’s AONBs. -

2.1.1 Supplemental Data Summary - A4155 Flowing Springs

2.1.1 Supplemental Data Summary - A4155 Flowing Springs Combined Option 1 & 2 Regrade and Gravity Wall Strategic Network • "The only impact for local service buses would be on the A4155: Carousel buses X80 service Monday-Saturday. Buses would need to divert via Binfield Heath/Dunsden Green" - Chris Spry's comments. •" Regarding the Playhatch area we have ATC 187 just south of the roundabout and have attached the weeks’ worth of flows from 2016 (AADT = 17603). North of the roundabout in 2010 we carried out a speed survey and the flows from this provide an AADT = 8359. Further along the A4155 just south of Henley we have a 2016 AADT = 10825. There are plenty of opportunities to loose vehicles between these two count sites (including Lower Shiplake) so the 2010 AADT is possibly a little low compared to what a 2016 survey would show but overall probably not too far out." - Richard Bowman's comments • "This is a significant route and a link road between the bridges crossing the river Thames particularly in this area that links to the Playhatch bridge on the B478 which takes large volumes of peak time traffic across the river Thames, if the A4155 were to close it would cause significant traffic problems in Henley and on Henley bridge in particular as well as having a major impact on the two river bridges in Reading. It’s closure would severely impact on bus routes in the area. " - Bob Eeles comments • 8000 AADT in 2015. See table 2.1.2; 2.1.3 Strategic Commercial – Impact • "A4155 – I am finding it difficult to see the location plan so cannot be sure of the to businesses, schools and impact of the closure. -

Download Map (PDF)

We’re delighted to present three circular walks all starting and ending at The New Inn. The Brakspear Pub Trails are a series of circular walks. We thought the idea of a variety of circular country walks all starting and ending at our pubs was a guaranteed winner. We have fantastic pubs nestled in the countryside, and we hope our maps are a great way for you to get out and enjoy some fresh air and a gentle walk, with a guaranteed drink at the end – perfect! Our pubs have always welcomed walkers (and almost all of them welcome dogs too), so we’re making it even easier with plenty of free maps. You can pick up copies in the pubs taking part or go to brakspearaletrails.co.uk to download them. We’re planning to add new pubs onto them, so the best place to check for the latest maps available is always our website. We absolutely recommend you book a table so that when you finish your walk you can enjoy a much needed bite to eat too. At the weekend, please book in advance, as this is often a busier time, especially our smaller pubs. And finally, do send us your photos of you out and about on your walk. We really do love getting them. @BrakspearPubs How to get there Driving: Postcode is RG4 9AU and there is a car park for customers. Nearest station: Tilehurst 6.4 miles away. Local bus services: The 25 pink bus service (Reading Buses) stops in Sonning Common on Wood Lane. -

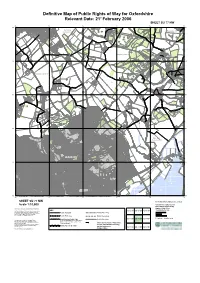

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21St February 2006 Colour SHEET SU 77 NW

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21st February 2006 Colour SHEET SU 77 NW 70 71 72 73 74 75 CHERITON PL CHERITON 7700 0002 2300 4400 0002 Water B 481 0005 0002 Ewhurst PLACE 242/12 242/11 Willow Tel Ex House 80 Pumping 80 Kidmore End READE'S LANE Trigfa Sta War Memorial Hall Pond 242/8 Batten House Pengelly OD LANE Garage ELM COURT WO Simmondley 421/3 LEA ROAD Woodstock High Timbers The Lodge 9693 Kedge ELM CT 421/4 4 Whitehill Aberdour Dene Cottage GROVE ROAD The 2/ epers Cottage Ke Birches 7190 MAPLE CLOSE Sonning Springhill 24 9387 LEA ROAD ROWAN CLOSE Pond Crowsley Park House Harpsden CP Well Pond CLOSE BIRCH CL 0084 0084 9285 BIRCH Pump Common CP House Chiltern Edge School WESTLEIGH DRIVE The White Cottage WESTLEIGH DRIVE Well 421/3 242/12 2178 4775 0076 242/11 2775 0076 2 0074 The Herb Farm Frieze Farm 4772 0071 0071 0871 KIDMORE LANE 350/1 South Lodge 3570 KENNYLANDS ROAD 8769 Works ILEX CLOSE 5367 0067 0067 4764 0064 421/6 5364 0064 242/7 2662 Charters 0060 0060 Pond 5760 SONNING Frieze 266/10 Cottage 421/1 421/5 9857 421/1 COMMON PEPP ARD ROAD 6354 Timber Well Well Cottage 421/28 2353 Jasmine 7052 Cottage Cort Holly Tree Farm Bungalow Well House BIRD WOOD COURT 421/4 0650 6349 7549 Holly Hagpits House Tree 0048 0048 Cottage Pump 5447 House 5847 6945 266/24 0043 1442 2642 The 0042 0042 421/2 Dorian Centre 421/4 Hagpits 7040 Orchard Pond ESSEX 6544 Well Pond BONES LANE 9237 WAY 421/6 Fords Cottage Crowsley SquirrelsThe Drain Grange 5236 Well 4635 Sunnyview 6636 Bottle and Glass Nursing Home -

Reservation Pack

SUBJECT TO CONTRACT & REFERENCES - PROPERTY RESERVATION FORM Reservation Monies: £500 Date Received: «PRINT_DATE» Property Held: «PROPERTY_ADDRESS1» «P ROPERTY_ADDRESS2» «PROPERTY_TOWN» «PROPERTY_POSTCODE» Rent Agreed: £«RENT_AMOUNT» pcm Anticipated Tenancy Start: «TENANCY_START_DAT E» Term: «INTIAL_TERM» (if 12 months is a break clause required Yes/No) Express Check In: Yes/No Zero Deposit Scheme: Additional Clauses Agreed (in relation to the Special Tenancy Conditions detailed within the tenancy agreement): Agreed pre-tenancy actions: Names and ages of children under 18: Please list any pets: Do any proposed tenants have adverse credit history? If yes specify: Will any proposed tenants receive housing benefit? If yes specify: 1. The property will be reserved in your name for a period of two weeks from the date of this reservation. We may show it to other people but no other tenancy applications will be accepted while the property is being held for you. 2. You can cancel your application within one working day in writing whereby your £500 reservation monies will be refunded in full within 3 working days. 3. If you withdraw from the tenancy less than 14 days after this reservation, the monies will be returned to you less our application fee. If you withdraw your application 14 or more days after this reservation, the monies will be forfeited in full. 4. If you withdraw from the tenancy less than 14 days before the tenancy start date, the reservation monies will be forfeited in full. 5. If you fail references, the reservation monies will be forfeited in full. 6. You agree to the terms above and those in ‘Notes for Tenants’ & ‘Fees to Tenants’ copies of which are attached. -

Meeting with Warwickshire County Council

Summary of changes to subsidised services in the Wheatley, Thame & Watlington area Effective from SUNDAY 5th June 2011 ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... Line 40:- High Wycombe – Chinnor – Thame Broadly hourly service maintained, operated by Arriva the Shires. Only certain journeys will serve Towersey village, but Towersey will also be served by routes 120 and 123 (see below). Service 101:- Oxford – Garsington – Watlington A broadly hourly service maintained, operated by Thames Travel Monday to Saturday between Oxford City Centre and Garsington. Certain peak buses only will start from or continue to Chalgrove and Watlington, this section otherwise will be served by route 106 (see below). Service 101 will no longer serve Littlehay Road or Rymers Lane, or the Cowley Centre (Nelson) stops. Nearest stops will be at the Original Swan. Service 102:- Oxford – Horspath – Watlington This Friday and Saturday evening service to/from Oxford City is WITHDRAWN. Associated commercial evening journeys currently provided on route 101 by Thames Travel will also be discontinued. Service 103:- Oxford – Horspath – Wheatley – Great Milton - Little Milton Service 104:- Oxford – Horspath – Wheatley – Great Milton – Cuddesdon /Denton A broadly hourly service over the Oxford – Great Milton section will continue to be operated by Heyfordian Travel Mondays to Saturdays. Buses will then serve either Little Milton (via the Haseleys) or Cuddesdon / Denton alternately every two hours as now. The route followed by service 104 will be amended in the Great Milton area and the section of route from Denton to Garsington is discontinued. Routes 103 and 104 will continue to serve Littlehay Road and Rymers Lane and Cowley (Nelson) stops. Service 113 is withdrawn (see below). -

October 2019 BUS INFORMATION the Following Bus Companies

October 2019 BUS INFORMATION The following bus companies operate buses to Gillotts School. Horseman Coaches 01189 753811 www.horsemancoaches.co.uk M&M Coaches 01494 761926 www.mmcoaches.co.uk Sprinters Travel 01628 200052 www.sprinterstravel.co.uk Whites Coaches (local public bus service) 01865 340516 www.whitescoaches.com Arriva (local public bus service) 0344 8004411 www.arrivabus.co.uk Oxfordshire County Council may provide free transport (or meet the cost of travel) for your child if he or she has to travel more than three miles to school, providing Gillotts School is your nearest available school. This distance is measured as the nearest available safe walking route. They may also provide free transport if your child is eligible for free school meals or you are on a low income. If you think your child may be eligible for this support, please contact Oxfordshire County Council, Quality Management Team 01865 323500 or [email protected] Alternatively, parents may be able to pay for spare seats on school buses operating for students who qualify for statutory transport. More information regarding this can be found on the Oxfordshire County Council website. There are also local public buses that serve Gillotts School. Parents of pupils who live closer to another available school but choose to come to Gillotts should contact the bus company operating the route nearest to their home to make their own arrangements. Transport costs for pupils in these circumstances are the responsibility of parents. The current bus routes are attached but stops and times do vary slightly from year to year depending on demand so it is best to check with the relevant bus companies direct and not rely solely on this information. -

Bhpc May 2021 Minutes

BINFIELD HEATH PARISH COUNCIL Minutes of the Binfield Heath Parish Council Meeting held on Monday May 24th 2021 at 6.30pm by Zoom ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Meeting of the Recreation Ground Charities & Allotment for the Labouring Poor Charity ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 012/21 Allotments One tenant has terminated his tenancy. The person next on the waiting list has been contacted. The Clerk will send a plan of tenant’s names to the Chairman. (Clerk to action) 013/21 Recreation Ground 013.01/21 Inspections have taken place and there are no problems. 013.02/21 Volunteers have offered to repair and improve the car park. Some equipment may need to be used. Cllr Ransom will ascertain what equipment so that the insurance company can be consulted. Cllr Ransom and Clerk to action) 013.03/21 A litter bin for the cleared area at the bottom of Arch Hill is to be purchased. (Clerk to action) 014/21 Public Forum No comments from the public. The meeting of the Parish Council Present Cllr P Rollason, Cllr L Ransom, Cllr H Lacey, Cllr Sarah Fulton-Urry, Cllr S Summerland, Cllr R. Davis, Cllr D Bartholomew (OCC, SODC), Cllr L Rawlins (SODC), five members of the public. 052/21 Apologies. None 053/21 Declarations of Interest None 054/21 Minutes of the meetings held on Monday 26th April 2021. Cllr Summerland proposed the APM and APCM minutes were accepted as a true record. This was seconded by Cllr Fulton-Urry. All agreed. 055/21 Matters Arising All items on the agenda. 056/21 County Councillor's report Cllr Bartholomew was congratulated on his re-election. -

Green Park Village Local Area Guide

READING, BERKSHIRE LOCAL AREA GUIDE Reading 1 READING, BERKSHIRE Contents WELCOME TO Live Local 2–3 Green Park Village Parks & Days Out 4–5 Eating Out 6–7 A new lakeside village of New England inspired Health & Wellbeing 8–9 houses and apartments in Reading, Berkshire, Sports & Leisure 10–11 Green Park Village offers the chance to become part Retail Therapy 12–13 of a thriving new community. Arts & Culture 14–15 If you enjoy dining out there is a wide selection of Educational Facilities 16–17 bars, restaurants and cafés nearby. Green Park Village Better Connected 18–19 is also within easy reach of a good selection of entertainment and shopping amenities. Doctors & Hospitals 20 Within this guide we uncover some of the best places to eat, drink, shop, live and explore, all within close proximity of Green Park Village. 2 1 GREEN PARK VILLAGE LOCAL AREA GUIDE LAKES COFFEE POD NUFFIELD HEALTH The lake at Green Park Village 0.7 miles away READING FITNESS LIVE is a beautiful setting for your Coffee Pod café is open & WELLBEING GYM life outdoors with play and throughout the working day, 0.9 miles away offering tasty breakfasts and a picnic areas and viewing State-of-the-art facilities for great selection of lunches. platforms. In addition, everyone including a 20-metre Longwater Lake at Green 100 Brook Drive, Green Park, swimming pool, gymnasium, Local Park Village also offers rowing Reading RG2 6UG health and beauty spa, exercise and fishing opportunities. greenpark.co.uk classes and lounge bar. At Green Park Village enjoy effortless living with all the Permission will be required from the Business Park. -

DUNSDEN WAY | BINFIELD HEATH | HENLEY-ON-THAMES | RG9 4LE Marraways & Oakleigh

Marraways & Oakleigh DUNSDEN WAY | BINFIELD HEATH | HENLEY-ON-THAMES | RG9 4LE Marraways & Oakleigh An exclusive development of two spacious five bedroom country houses, enjoying southerly facing rear gardens, of just under half an acre, backing onto open farmland Computer generated impression of Marraways These two individual family homes, each have an additional home office/studio above the detached double garages and are set in delightful landscaped grounds, with mature trees and shrubs, backing onto open farmland. N MARRAWAYS OAKLEIGH DUNSDEN WAY Computer generated impression of Oakleigh Computer generated artist impressions of interior rooms Built of traditional construction, over three floors, with gas There are five generous double bedrooms, with four bath/ underfloor heating to ground floor. The spacious reception shower rooms. Over the detached double garage there is areas flow beautifully, with a large kitchen/breakfast room a separate office/studio which has its own shower/WC. and sitting room opening out onto the patio and gardens. Computer generated impressions of interior rooms • Built in a traditional manner with external walls of facing brickwork, • Kitchen designed and installed by Optiplan • Sash windows insulated cavity and inner skin blockwork Specification • Fully equipped with electrical appliances • Solid wood front door • 10 year warranty from CRL • Silestone worktops with upstands • Wood burning stove to sitting room • Detached double garage with an office/studio room above, • Utility room with ‘butler sink’ •