Deformation Processes at the Leading Edge of the Sevier Fold and Thrust Belt, Southwest Utah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linking Megathrust Earthquakes to Brittle Deformation in a Fossil Accretionary Complex

ARTICLE Received 9 Dec 2014 | Accepted 13 May 2015 | Published 24 Jun 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8504 OPEN Linking megathrust earthquakes to brittle deformation in a fossil accretionary complex Armin Dielforder1, Hauke Vollstaedt1,2, Torsten Vennemann3, Alfons Berger1 & Marco Herwegh1 Seismological data from recent subduction earthquakes suggest that megathrust earthquakes induce transient stress changes in the upper plate that shift accretionary wedges into an unstable state. These stress changes have, however, never been linked to geological structures preserved in fossil accretionary complexes. The importance of coseismically induced wedge failure has therefore remained largely elusive. Here we show that brittle faulting and vein formation in the palaeo-accretionary complex of the European Alps record stress changes generated by subduction-related earthquakes. Early veins formed at shallow levels by bedding-parallel shear during coseismic compression of the outer wedge. In contrast, subsequent vein formation occurred by normal faulting and extensional fracturing at deeper levels in response to coseismic extension of the inner wedge. Our study demonstrates how mineral veins can be used to reveal the dynamics of outer and inner wedges, which respond in opposite ways to megathrust earthquakes by compressional and extensional faulting, respectively. 1 Institute of Geological Sciences, University of Bern, Baltzerstrasse 1 þ 3, Bern CH-3012, Switzerland. 2 Center for Space and Habitability, University of Bern, Sidlerstrasse 5, Bern CH-3012, Switzerland. 3 Institute of Earth Surface Dynamics, University of Lausanne, Geˆopolis 4634, Lausanne CH-1015, Switzerland. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to A.D. (email: [email protected]). NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | 6:7504 | DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8504 | www.nature.com/naturecommunications 1 & 2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited. -

Tectonics of the Musandam Peninsula and Northern Oman Mountains: from Ophiolite Obduction to Continental Collision

GeoArabia, 2014, v. 19, no. 2, p. 135-174 Gulf PetroLink, Bahrain Tectonics of the Musandam Peninsula and northern Oman Mountains: From ophiolite obduction to continental collision Michael P. Searle, Alan G. Cherry, Mohammed Y. Ali and David J.W. Cooper ABSTRACT The tectonics of the Musandam Peninsula in northern Oman shows a transition between the Late Cretaceous ophiolite emplacement related tectonics recorded along the Oman Mountains and Dibba Zone to the SE and the Late Cenozoic continent-continent collision tectonics along the Zagros Mountains in Iran to the northwest. Three stages in the continental collision process have been recognized. Stage one involves the emplacement of the Semail Ophiolite from NE to SW onto the Mid-Permian–Mesozoic passive continental margin of Arabia. The Semail Ophiolite shows a lower ocean ridge axis suite of gabbros, tonalites, trondhjemites and lavas (Geotimes V1 unit) dated by U-Pb zircon between 96.4–95.4 Ma overlain by a post-ridge suite including island-arc related volcanics including boninites formed between 95.4–94.7 Ma (Lasail, V2 unit). The ophiolite obduction process began at 96 Ma with subduction of Triassic–Jurassic oceanic crust to depths of > 40 km to form the amphibolite/granulite facies metamorphic sole along an ENE- dipping subduction zone. U-Pb ages of partial melts in the sole amphibolites (95.6– 94.5 Ma) overlap precisely in age with the ophiolite crustal sequence, implying that subduction was occurring at the same time as the ophiolite was forming. The ophiolite, together with the underlying Haybi and Hawasina thrust sheets, were thrust southwest on top of the Permian–Mesozoic shelf carbonate sequence during the Late Cenomanian–Campanian. -

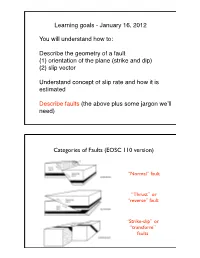

Describe the Geometry of a Fault (1) Orientation of the Plane (Strike and Dip) (2) Slip Vector

Learning goals - January 16, 2012 You will understand how to: Describe the geometry of a fault (1) orientation of the plane (strike and dip) (2) slip vector Understand concept of slip rate and how it is estimated Describe faults (the above plus some jargon weʼll need) Categories of Faults (EOSC 110 version) “Normal” fault “Thrust” or “reverse” fault “Strike-slip” or “transform” faults Two kinds of strike-slip faults Right-lateral Left-lateral (dextral) (sinistral) Stand with your feet on either side of the fault. Which side comes toward you when the fault slips? Another way to tell: stand on one side of the fault looking toward it. Which way does the block on the other side move? Right-lateral Left-lateral (dextral) (sinistral) 1992 M 7.4 Landers, California Earthquake rupture (SCEC) Describing the fault geometry: fault plane orientation How do you usually describe a plane (with lines)? In geology, we choose these two lines to be: • strike • dip strike dip • strike is the azimuth of the line where the fault plane intersects the horizontal plane. Measured clockwise from N. • dip is the angle with respect to the horizontal of the line of steepest descent (perpendic. to strike) (a ball would roll down it). strike “60°” dip “30° (to the SE)” Profile view, as often shown on block diagrams strike 30° “hanging wall” “footwall” 0° N Map view Profile view 90° W E 270° S 180° Strike? Dip? 45° 45° Map view Profile view Strike? Dip? 0° 135° Indicating direction of slip quantitatively: the slip vector footwall • let’s define the slip direction (vector) -

Geotectonic Model of the Alpine Development of Lakavica Graben in the Eastern Part of the Vardar Zone in the Republic of Macedonia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UGD Academic Repository Geologica Macedonica, Vol. 27, No. 1, pp. 87–93 (2013) GEOME 2 ISSN 0352 – 1206 Manuscript received: May 17, 2013 UDC: 551.245.03(497.71/.73) Accepted: October 25, 2013 Original scientific paper GEOTECTONIC MODEL OF THE ALPINE DEVELOPMENT OF LAKAVICA GRABEN IN THE EASTERN PART OF THE VARDAR ZONE IN THE REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA Goše Petrov, Violeta Stojanova, Gorgi Dimov Faculty of Natural and Technical Sciences, “Goce Delčev” University, P.O.Box 201, MK 2000 Štip, Republic of Macedonia [email protected]//[email protected] A b s t r a c t: Lakavica graben is located in the eastern subzone of the Vardar zone, which during the Alpine orogenesis was covered with very complex processes of tectogenesis. On the area of about 200 km2, in the Lakavica graben, are present geological units from the oldest geological periods (Precam- brian) to the youngest (Neogene and Quaternary). Tectonic structure, or rupture tectonic, is very intense developed and gives possibility for analysis of the geotectonic processes in the Alpine orogen phase. This paper presents the possible model for geotectonic processes in the Lakavica graben, according to which can be generalized geotectonic processes in the Vardar zone during the Alpine orogeny. Key words: Lakavica graben; geotectonic model; Alpine orogeny; Vardar zone INTRODUCTION Vardar zone as a tectonic unit, for the first niki Gulf (Greece), than bent eastward and crosses time, is separated and showed on the "Geological- the ophiolite zone Izmir–Ankara (Turkey). -

Along Strike Variability of Thrust-Fault Vergence

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2014-06-11 Along Strike Variability of Thrust-Fault Vergence Scott Royal Greenhalgh Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Geology Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Greenhalgh, Scott Royal, "Along Strike Variability of Thrust-Fault Vergence" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 4095. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4095 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Along Strike Variability of Thrust-Fault Vergence Scott R. Greenhalgh A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science John H. McBride, Chair Brooks B. Britt Bart J. Kowallis John M. Bartley Department of Geological Sciences Brigham Young University April 2014 Copyright © 2014 Scott R. Greenhalgh All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Along Strike Variability of Thrust-Fault Vergence Scott R. Greenhalgh Department of Geological Sciences, BYU Master of Science The kinematic evolution and along-strike variation in contractional deformation in over- thrust belts are poorly understood, especially in three dimensions. The Sevier-age Cordilleran overthrust belt of southwestern Wyoming, with its abundance of subsurface data, provides an ideal laboratory to study how this deformation varies along the strike of the belt. We have per- formed a detailed structural interpretation of dual vergent thrusts based on a 3D seismic survey along the Wyoming salient of the Cordilleran overthrust belt (Big Piney-LaBarge field). -

From Orogeny to Rifting: When and How Does Rifting Begin? Insights from the Norwegian ‘Reactivation Phase’

EGU21-469 https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu21-469 EGU General Assembly 2021 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. From orogeny to rifting: when and how does rifting begin? Insights from the Norwegian ‘reactivation phase’. Gwenn Peron-Pinvidic1,2, Per Terje Osmundsen2, Loic Fourel1, and Susanne Buiter3 1NGU - Geological Survey of Norway, 7040 Trondheim, Norway 2NTNU - Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 7491 Trondheim, Norway 3Tectonics and Geodynamics, RWTH Aachen University, 52064 Aachen, Germany Following the Wilson Cycle theory, most rifts and rifted margins around the world developed on former orogenic suture zones (Wilson, 1966). This implies that the pre-rift lithospheric configuration is heterogeneous in most cases. However, for convenience and lack of robust information, most models envisage the onset of rifting based on a homogeneously layered lithosphere (e.g. Lavier and Manatschal, 2006). In the last decade this has seen a change, thanks to the increased academic access to high-resolution, deeply imaging seismic datasets, and numerous studies have focused on the impact of inheritance on the architecture of rifts and rifted margins. The pre-rift tectonic history has often been shown as strongly influencing the subsequent rift phases (e.g. the North Sea case - Phillips et al., 2016). In the case of rifts developing on former orogens, one important question relates to the distinction between extensional structures formed during the orogenic collapse and the ones related to the proper onset of rifting. The collapse deformation is generally associated with polarity reversal along orogenic thrusts, ductile to brittle deformation and important crustal thinning with exhumation of deeply buried rocks (Andersen et al., 1994; Fossen, 2000). -

Development of the Rocky Mountain Foreland Basin: Combined Structural

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2007 DEVELOPMENT OF THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN FORELAND BASIN: COMBINED STRUCTURAL, MINERALOGICAL, AND GEOCHEMICAL ANALYSIS OF BASIN EVOLUTION, ROCKY MOUNTAIN THRUST FRONT, NORTHWEST MONTANA Emily Geraghty Ward The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ward, Emily Geraghty, "DEVELOPMENT OF THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN FORELAND BASIN: COMBINED STRUCTURAL, MINERALOGICAL, AND GEOCHEMICAL ANALYSIS OF BASIN EVOLUTION, ROCKY MOUNTAIN THRUST FRONT, NORTHWEST MONTANA" (2007). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1234. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1234 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEVELOPMENT OF THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN FORELAND BASIN: COMBINED STRUCTURAL, MINERALOGICAL, AND GEOCHEMICAL ANALYSIS OF BASIN EVOLUTION ROCKY MOUNTAIN THRUST FRONT, NORTHWEST MONTANA By Emily M. Geraghty Ward B.A., Whitman College, Walla Walla, WA, 1999 M.S., Washington State University, Pullman, WA, 2002 Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geology The University of Montana Missoula, MT Spring 2007 Approved by: Dr. David A. Strobel, Dean Graduate School James W. Sears, Chair Department of Geosciences Julia A. Baldwin Department of Geosciences Marc S. Hendrix Department of Geosciences Steven D. -

The Tectonic Evolution of the Madrean Archipelago and Its Impact on the Geoecology of the Sky Islands

The Tectonic Evolution of the Madrean Archipelago and Its Impact on the Geoecology of the Sky Islands David Coblentz Earth and Environmental Sciences Division, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM Abstract—While the unique geographic location of the Sky Islands is well recognized as a primary factor for the elevated biodiversity of the region, its unique tectonic history is often overlooked. The mixing of tectonic environments is an important supplement to the mixing of flora and faunal regimes in contributing to the biodiversity of the Madrean Archipelago. The Sky Islands region is located near the actively deforming plate margin of the Western United States that has seen active and diverse tectonics spanning more than 300 million years, many aspects of which are preserved in the present-day geology. This tectonic history has played a fundamental role in the development and nature of the topography, bedrock geology, and soil distribution through the region that in turn are important factors for understanding the biodiversity. Consideration of the geologic and tectonic history of the Sky Islands also provides important insights into the “deep time” factors contributing to present-day biodiversity that fall outside the normal realm of human perception. in the North American Cordillera between the Sierra Madre Introduction Occidental and the Colorado Plateau – Southern Rocky The “Sky Island” region of the Madrean Archipelago (lo- Mountains (figure 1). This part of the Cordillera has been cre- cated between the northern Sierra Madre Occidental in Mexico ated by the interactions between the Pacific, North American, and the Colorado Plateau/Rocky Mountains in the Southwest- Farallon (now entirely subducted under North America) and ern United States) is an area of exceptional biodiversity and has Juan de Fuca plates and is rich in geology features, including become an important study area for geoecology, biology, and major plateaus (The Colorado Plateau), large elevated areas conservation management. -

THE GROWTH of SHEEP MOUNTAIN ANTICLINE: COMPARISON of FIELD DATA and NUMERICAL MODELS Nicolas Bellahsen and Patricia E

THE GROWTH OF SHEEP MOUNTAIN ANTICLINE: COMPARISON OF FIELD DATA AND NUMERICAL MODELS Nicolas Bellahsen and Patricia E. Fiore Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305 e-mail: [email protected] be explained by this deformed basement cover interface Abstract and does not require that the underlying fault to be listric. In his kinematic model of a basement involved We study the vertical, compression parallel joint compressive structure, Narr (1994) assumes that the set that formed at Sheep Mountain Anticline during the basement can undergo significant deformations. Casas early Laramide orogeny, prior to the associated folding et al. (2003), in their analysis of field data, show that a event. Field data indicate that this joint set has a basement thrust sheet can undergo a significant heterogeneous distribution over the fold. It is much less penetrative deformation, as it passes over a flat-ramp numerous in the forelimb than in the hinge and geometry (fault-bend fold). Bump (2003) also discussed backlimb, and in fact is absent in many of the forelimb how, in several cases, the basement rocks must be field measurement sites. Using 3D elastic numerical deformed by the fault-propagation fold process. models, we show that early slip along an underlying It is noteworthy that basement deformation often is thrust fault would have locally perturbed the neglected in kinematic (Erslev, 1991; McConnell, surrounding stress field, inducing a compression that 1994), analogue (Sanford, 1959; Friedman et al., 1980), would inhibit joint formation above the fault tip. and numerical models. This can be attributed partially Relating the absence of joints in the forelimb to this to the fact that an understanding of how internal stress perturbation, we are able to constrain the deformation is delocalized in the basement is lacking. -

Pan-African Orogeny 1

Encyclopedia 0f Geology (2004), vol. 1, Elsevier, Amsterdam AFRICA/Pan-African Orogeny 1 Contents Pan-African Orogeny North African Phanerozoic Rift Valley Within the Pan-African domains, two broad types of Pan-African Orogeny orogenic or mobile belts can be distinguished. One type consists predominantly of Neoproterozoic supracrustal and magmatic assemblages, many of juvenile (mantle- A Kröner, Universität Mainz, Mainz, Germany R J Stern, University of Texas-Dallas, Richardson derived) origin, with structural and metamorphic his- TX, USA tories that are similar to those in Phanerozoic collision and accretion belts. These belts expose upper to middle O 2005, Elsevier Ltd. All Rights Reserved. crustal levels and contain diagnostic features such as ophiolites, subduction- or collision-related granitoids, lntroduction island-arc or passive continental margin assemblages as well as exotic terranes that permit reconstruction of The term 'Pan-African' was coined by WQ Kennedy in their evolution in Phanerozoic-style plate tectonic scen- 1964 on the basis of an assessment of available Rb-Sr arios. Such belts include the Arabian-Nubian shield of and K-Ar ages in Africa. The Pan-African was inter- Arabia and north-east Africa (Figure 2), the Damara- preted as a tectono-thermal event, some 500 Ma ago, Kaoko-Gariep Belt and Lufilian Arc of south-central during which a number of mobile belts formed, sur- and south-western Africa, the West Congo Belt of rounding older cratons. The concept was then extended Angola and Congo Republic, the Trans-Sahara Belt of to the Gondwana continents (Figure 1) although West Africa, and the Rokelide and Mauretanian belts regional names were proposed such as Brasiliano along the western Part of the West African Craton for South America, Adelaidean for Australia, and (Figure 1). -

G17 Laramide and Sevier Orogenies

PLATE TECTONICS 423 g17 Laramide and Sevier orogenies < cratonal uplifts, thin-skinned thrust tectonics > ... mountains were thought of ... as punishments dealt to Earth by a Creator disappointed at the misbehavior of its inhabitants. This “catastrophist” view affected ... 18th and early 19th centuries, well-born ladies making the Grand Tour in Europe would pull down their window shades to avoid viewing the Alps. —Donald Kennedy.1 The fold-thrust belt of the northern Rocky Mountains is a back-arc east of the Cascade volcanic- mountains and sediment-filled trench of the eastward subducting Juan da Fuca oceanic plate. The central Rocky Mountains is earthquake-active. Its scenery is of a maturely dissected broad-uparch that in erosional section and by exhumation exposes features of the once Laramide mountain chain. The Wyoming Basin and southern Rocky Mountains is a region of reactivated Laramide cratonal uplifts. To the west of the southern Rocky Mountains and Colorado Plateau is the Basin and Range physiographic province. Its graben and horst scenery results from ongoing extension that has doubled the width of the region since the middle Cenozoic. Created are large displacements on listric faults that at their surfacing ends are imbricate normal faulted. This mimics in reverse the geometry produced by a former compressive orogeny called the Sevier.2 Laramide orogeny (Paleocene climax, near the end of the Cretaceous inception.) Laramide refers to ore-producing intrusions (as Boulder batholith, Montana), eastward-shed foreland- basin sediments as the E-K boundary containing undeformed Arapahoe Conglomerate fm and the folded Cretaceous Mesa Verde fm, Colorado.3 These strata are disconformable on Late Cretaceous Interior Seaway Laramic fm that is nonconformable on a Precambrian basement complex Laramide folds and faults resulted from block faulting and thrust faulting of this underlying craton. -

The Penokean Orogeny in the Lake Superior Region Klaus J

Precambrian Research 157 (2007) 4–25 The Penokean orogeny in the Lake Superior region Klaus J. Schulz ∗, William F. Cannon U.S. Geological Survey, 954 National Center, Reston, VA 20192, USA Received 16 March 2006; received in revised form 1 September 2006; accepted 5 February 2007 Abstract The Penokean orogeny began at about 1880 Ma when an oceanic arc, now the Pembine–Wausau terrane, collided with the southern margin of the Archean Superior craton marking the end of a period of south-directed subduction. The docking of the buoyant craton to the arc resulted in a subduction jump to the south and development of back-arc extension both in the initial arc and adjacent craton margin to the north. A belt of volcanogenic massive sulfide deposits formed in the extending back-arc rift within the arc. Synchronous extension and subsidence of the Superior craton resulted in a broad shallow sea characterized by volcanic grabens (Menominee Group in northern Michigan). The classic Lake Superior banded iron-formations, including those in the Marquette, Gogebic, Mesabi and Gunflint Iron Ranges, formed in that sea. The newly established subduction zone caused continued arc volcanism until about 1850 Ma when a fragment of Archean crust, now the basement of the Marshfield terrane, arrived at the subduction zone. The convergence of Archean blocks of the Superior and Marshfield cratons resulted in the major contractional phase of the Penokean orogeny. Rocks of the Pembine–Wausau arc were thrust northward onto the Superior craton causing subsidence of a foreland basin in which sedimentation began at about 1850 Ma in the south (Baraga Group rocks) and 1835 Ma in the north (Rove and Virginia Formations).