Factors Affecting Anfo Fumes Production

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conventional Explosions and Blast Injuries 7

Chapter 7: CONVENTIONAL EXPLOSIONS AND BLAST INJURIES David J. Dries, MSE, MD, FCCM David Bracco, MD, EDIC, FCCM Tarek Razek, MD Norma Smalls-Mantey, MD, FACS, FCCM Dennis Amundson, DO, MS, FCCM Objectives ■ Describe the mechanisms of injury associated with conventional explosions. ■ Outline triage strategies and markers of severe injury in patients wounded in conventional explosions. ■ Explain the general principles of critical care and procedural support in mass casualty incidents caused by conventional explosions. ■ Discuss organ-specific support for victims of conventional explosions. Case Study Construction workers are using an acetylene/oxygen mixture to do some welding work in a crowded nearby shopping mall. Suddenly, an explosion occurs, shattering windows in the mall and on the road. The acetylene tank seems to be at the origin of the explosion. The first casualties arrive at the emergency department in private cars and cabs. They state that at the scene, blood and injured people are everywhere. - What types of patients do you expect? - How many patients do you expect? - When will the most severely injured patients arrive? - What is your triage strategy, and how will you triage these patients? - How do you initiate care in victims of conventional explosions? Fundamental Disaster Management I . I N T R O D U C T I O N Detonation of small-volume, high-intensity explosives is a growing threat to civilian as well as military populations. Understanding circumstances surrounding conventional explosions helps with rapid triage and recognition of factors that contribute to poor outcomes. Rapid evacuation of salvageable victims and swift identification of life-threatening injuries allows for optimal resource utilization and patient management. -

Jones (Stephen) Oklahoma City Bombing Archive, 1798 – 2003 (Bulk 1995 – 1997)

JONES (STEPHEN) OKLAHOMA CITY BOMBING ARCHIVE, 1798 ± 2003 (BULK 1995 ± 1997). See TARO record at http://www.lib.utexas.edu/taro/utcah/03493/cah-03493.html (Approximately 620 linear feet) This collection is open for research use. Portions are restricted due to privacy concerns. See Archivist's Note for more details. Use of DAT and Beta tapes by appointment only; please contact repository for more information. This collection is stored remotely. Advance notice required for retrieval. Contact repository for retrieval. Cite as: Stephen Jones Oklahoma City Bombing Archive, 1798 ± 2003 (Bulk 1995 ± 1997), Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin. [AR 98-395; 2003-055; 2005-161] ______________________________________________________________________________ BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE: Stephen Jones (born 1940) was appointed in May 1995 by the United States District Court in Oklahoma City to serve as the lead defense attorney for Timothy McVeigh in the criminal court case of United States of America v. Timothy James McVeigh and Terry Lynn Nichols. On April 19, 1995, two years to the day after the infamous Federal Bureau of Investigation and Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms raid on the Branch Davidians at Waco, Texas, a homemade bomb delivered inside of a Ryder rental truck was detonated in front of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Timothy McVeigh, as well as his accomplice Terry Nichols, were accused of and, in 1997, found guilty of the crime, and McVeigh was executed in 2001. Terry Nichols is still serving his sentence of 161 consecutive life terms without the possibility of parole in the ADX Florence super maximum-security prison in Florence, Colorado. -

Chemical Accident Prevention & Preparedness

Lessons Learned Bulletin No. 5 Chemical Accident Prevention & Preparedness Major accidents involving fertilizers The aim of the bulletin is to provide insights on lessons learned from accident reported in the European Major Accident Reporting System (eMARS) and other accident sources for both industry operators and government regulators. In future the CAPP Lessons Learned Bulletin will be produced on a semi-annual basis. Each issue of the Bulletin focuses on a particular theme. Accident 1 Summary Wholesale and retail storage and distribution In preparing this bulletin, 25 major accidents in eMARS involving fertiliz- Sequence of events was to attack the source of the fire with ers were studied together with an ad- portable fire extinguishers, in the absence ditional 25 accidents from other free A fire occurred in a warehouse storing fer- of activated fire hose reels. Arriving on sources, including also accidents in tilizers and chemical products belonging the site, firemen observed that very thick transport. Events were chosen on the to a wholesale distributor of numerous smoke was emitted from the storage basis that ammonium nitrate or NPK products, including sugar, molasses, fer- compartment. It also appeared that a fertilizer (nitrogen-phosphorus-potas- tilizers, and cereals. The storage instal- fire was burning beneath the mass. How- sium) was involved in the accident. lation was subdivided into 8 compart- ever, the intervention of the firefighters ments of which two contained NPK (15% appeared to focus solely on the presence In general, with some exceptions, N, 8% P, 22% K) fertilizers in quantities of ammonium nitrate fertilizer, ignoring, most accidents occurred in ware- of 600 tonnes and 850 tonnes respec- the nature of the other chemical prod- houses or general chemicals manu- tively. -

The Texas City Disaster

National Hazardous Materials Fusion Center HAZMAT HISTORY The Texas City Disaster The National Hazardous Materials Fusion Center offers Hazmat History as an avenue for responders to learn from the past and apply those lessons learned to future incidents for a more successful outcome. This coincides with the overarching mission of the Fusion Center – to improve hazmat responder safety and enhance the decision‐making process during pre‐planning and mitigation of hazmat incidents. Incident Details: Insert Location and Date Texas City, TX April 16, 1947 Hazardous Material Involved Ammonium Nitrate Fertilizer Type (mode of transportation, fixed facility) Cargo Ship Overview The morning of 16 April 1947 dawned clear and crisp, cooled by a brisk north wind. Just before 8 am, longshoremen removed the hatch covers on Hold 4 of the French Liberty ship Grandcamp as they prepared to load the remainder of a consignment of ammonium nitrate fertilizer. Some 2,086 mt (2,300 t) were already onboard, 798 (880) of which were in the lower part of Hold 4. The remainder of the ship's cargo consisted of large balls of sisal twine, peanuts, drilling equipment, tobacco, cotton, and a few cases of small ammunition. No special safety precautions were in focus at the time. Several longshoremen descended into the hold and waited for the first pallets holding the 45 kg (100 lb) packages to be hoisted from dockside. Soon thereafter, someone smelled smoke, a plume was observed rising between the cargo holds and the ship’s hull, apparently about seven or eight layers of sacks down. Neither a 3.8 L (1 gal) jug of drinking water nor the contents of two fire extinguishers supplied by crew members seemed to do much good. -

Toxic Fume Comparison of a Few Explosives Used in Trench Blasting

Toxic Fume Comparison of a Few Explosives Used in Trench Blasting By Marcia L. Harris, Michael J. Sapko, and Richard J. Mainiero National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Pittsburgh Research Laboratory ABSTRACT Since 1988, there have been 17 documented incidents in the United States and Canada in which carbon monoxide (CO) is suspected to have migrated through ground strata into occupied enclosed spaces as a result of proximate trench blasting or surface mine blasting. These incidents resulted in 39 suspected or medically verified carbon monoxide poisonings and one fatality. To better understand the factors contributing to this hazard, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) carried out studies in a 12-foot diameter sphere to identify key factors that may enhance the levels of CO associated with the detonation of several commercial trenching explosives. The gaseous detonation products from emulsions, a watergel, and ANFO blasting agents as well as gelatin dynamite, TNT, and Pentolite boosters were measured in an argon atmosphere and compared with those for the same explosives detonated in air. Test variables included explosive formulation, wrapper, aluminum addition, oxygen balance, and density. Major contributing factors to CO production, under these laboratory test conditions, are presented. The main finding is the high CO production associated with the lack of afterburning in an oxygen poor atmosphere. Fumes measurements are compared with the manufacturer’s reported IME fume class and with the Federal Relative Toxicity Standard 30 CFR Part 15 in order to gain an understanding of the relative toxicity of some explosives used in trench blasting. INTRODUCTION Toxic gases such as CO and NO are produced by the detonation of explosives. -

Chapter 2 EXPLOSIVES

Chapter 2 EXPLOSIVES This chapter classifies commercial blasting compounds according to their explosive class and type. Initiating devices are listed and described as well. Military explosives are treated separately. The ingredi- ents and more significant properties of each explosive are tabulated and briefly discussed. Data are sum- marized from various handbooks, textbooks, and manufacturers’ technical data sheets. THEORY OF EXPLOSIVES In general, an explosive has four basic characteristics: (1) It is a chemical compound or mixture ignited by heat, shock, impact, friction, or a combination of these conditions; (2) Upon ignition, it decom- poses rapidly in a detonation; (3) There is a rapid release of heat and large quantities of high-pressure gases that expand rapidly with sufficient force to overcome confining forces; and (4) The energy released by the detonation of explosives produces four basic effects; (a) rock fragmentation; (b) rock displacement; (c) ground vibration; and (d) air blast. A general theory of explosives is that the detonation of the explosives charge causes a high-velocity shock wave and a tremendous release of gas. The shock wave cracks and crushes the rock near the explosives and creates thousands of cracks in the rock. These cracks are then filled with the expanding gases. The gases continue to fill and expand the cracks until the gas pressure is too weak to expand the cracks any further, or are vented from the rock. The ingredients in explosives manufactured are classified as: Explosive bases. An explosive base is a solid or a liquid which, upon application or heat or shock, breaks down very rapidly into gaseous products, with an accompanying release of heat energy. -

Variables Associated with the Classification of Ammonium Nitrate – a Literature Review

Variables Associated with the Classification of Ammonium Nitrate – A Literature Review FINAL REPORT BY: Sean Gillis Sreenivasan Ranganathan Fire Protection Research Foundation, Quincy, MA March 2017 © 2017 Fire Protection Research Foundation 1 Batterymarch Park, Quincy, MA 02169-7417, USA Email: [email protected] | Web: nfpa.org/foundation —— Page ii —— FOREWORD Ammonium Nitrate (AN) “is a chemical compound produced in both solid and liquid forms that is commonly used in fertilizers”. The burning rate of technical-grade AN prill falls within the Class 2 oxidizer criteria in Annex G of NFPA 400, 2016. The loss history of AN also indicates potential for unstable reactive hazard properties, uncontrolled decomposition and/or detonation under circumstances that are not fully understood. In the most recent revision of NFPA 400, Hazardous Materials Code, the Technical Committee (TC) classified Ammonium Nitrate as a Class 2 Oxidizer. However recent hazardous material incidents involving AN have resulted in differing views regarding the reactivity of the compound and whether or not it should be considered an unstable reactive in NFPA 400. The different behaviors of AN in different fire situations make it difficult to determine the appropriate safe practices for AN storage and handling. There are also discrepancies between the NFPA and International Fire Code (IFC) classifications of Ammonium Nitrate. As a result there is a need for additional data to assist in the proper classification/treatment of AN. An examination of existing data involving the reactivity of AN will assist the NFPA 400 TC in determining the appropriate classification of Ammonium Nitrate, and perhaps point to a need for future Ammonium Nitrate testing. -

Guide for the Selection of Commercial Explosives Detection Systems For

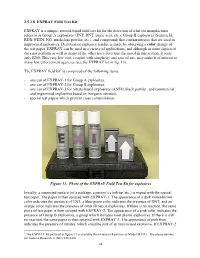

2.5.3.8 EXPRAY Field Test Kit EXPRAY is a unique, aerosol-based field test kit for the detection of what the manufacturer refers to as Group A explosives (TNT, DNT, picric acid, etc.), Group B explosives (Semtex H, RDX, PETN, NG, smokeless powder, etc.), and compounds that contain nitrates that are used in improvised explosives. Detection of explosive residue is made by observing a color change of the test paper. EXPRAY can be used in a variety of applications, and although in some aspects it does not perform as well as many of the other trace detectors discussed in this section, it costs only $250. This very low cost, coupled with simplicity and ease of use, may make it of interest to many law enforcement agencies (see the EXPRAY kit in fig. 13). The EXPRAY field kit2 is comprised of the following items: - one can of EXPRAY-1 for Group A explosives, - one can of EXPRAY-2 for Group B explosives, - one can of EXPRAY-3 for nitrate-based explosives (ANFO, black powder, and commercial and improvised explosives based on inorganic nitrates), - special test papers which prevent cross contamination. Figure 13. Photo of the EXPRAY Field Test Kit for explosives Initially, a suspected surface (of a package, a person’s clothing, etc.) is wiped with the special test paper. The paper is then sprayed with EXPRAY-1. The appearance of a dark violet-brown color indicates the presence of TNT, a blue-green color indicates the presence of DNT, and an orange color indicates the presence of other Group A explosives. -

Characterization and Analysis of Tetranitrate Esters Jimmie C

Characterization and Analysis of Tetranitrate Esters Jimmie C. Oxley; James, L. Smith; Joseph E. Brady, IV; Austin C. Brown University of Rhode Island, Chemistry Dept; Kingston, RI 02881 Abstract Thermal behaviors, vapor pressures, densities, and drop weight impact results, as well as analytical protocols, are reported for three tetranitrate esters: erythritol tetranitrate (ETN), 1,4‐ dinitrato‐2,3‐dinitro‐2,3bis(nitratomethylene) butane (DNTN), and pentaerythritol tetranitrate (PETN). ETN and DNTN both melt below 100oC and have ambient vapor pressures comparable to TNT. While LC/MS was shown to be a viable technique for analysis of all three tetranitrate esters, only ETN was successfully analyzed by GC/MS. Performance of these nitrate esters as evaluated in lab using the small-scale explosivity device (SSED) suggested RDX >> DNTN > PETN > ETN. Detonation velocities were calculated using Cheetah 6.0. Since the starting material is now widely available, it is likely that law enforcement will find ETN in future improvised explosive devices. This paper with its analytical schemes should prove useful in identification of this homemade explosive. Keywords: erythritol tetranitrate, ETN, 1,4‐dinitrato‐2,3‐dinitro‐2,3bis(nitratomethylene) butane, DNTN, pentaerythritol tetranitrate, PETN, vapor pressure, densities, drop weight impact, thermal behavior, HPLC‐HRMS 1. Introduction In recent years there has been growth in use of so-called “homemade” explosives (HME). Preparation of HME can require little synthetic expertise. It can be as simple as mixing oxidizers and fuels as opposed to the preparation and isolation of discrete compounds. When specific characteristics are required terrorists do engage in more complex synthetic procedures. -

Bombs, Explosions and Preparedness

Bombs, Explosions and Faculty Preparedness: A New Role for Public Ziad N. Kazzi, MD, FAAEM Health and First Assistant Professor Responders Co-Director Center for Emergency Infections & Satellite Conference and Live Webcast Emergency Preparedness Tuesday, March 27, 2007 Department of Emergency Medicine 12:00 - 1:30 p.m. (Central Time) University of Alabama at Birmingham Produced by the Alabama Department of Public Health Video Communications and Distance Learning Division Program Objectives FBI Reported Bombings, 1988-1997 • Describe important historical events involving explosions. • Discuss different clinical aspects of blast injuries. • Describe public health and first responder activities in reaction to explosions and blasts. FBI Bombing Database 1988-1997 FBI Bombing Database 2000 1916 1911 1880 1988-1997 1800 1600 1551 1552 • 17,579 bombings 1457 1400 1212 1200 • Numbers doubled over the 10 year 1000 931 period 800 641 Number of Bombings 593 582 600 538 545 423 427 406 378 • Number of bombing peaked in 1992 400 267 203 200 156 0 • 78% were explosives and 22% were 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 Explosive Bombing Years 1988-1997 incendiaries Incendiary Bombing FBI Bombing Database 1988-97 FBI Bombing Database 1988-1997 14001400 12001200 • 427 deaths with a peak in 1995 10001000 (Oklahoma City bombing) 800800 600 600 • 4,063 bomb-related injuries 400400 200200 Number of FBI Reported Deaths and Injuries Number of FBI Reported Deaths and Injuries • Incendiary bombs caused more 0 19881988 19891989 19901990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 injuries than explosives InjuriesInjuries Deaths Years 1998 - 1997 Special Characteristics of Special Characteristics of Bombing Victims Bombing Victims • Bombing resulted in significantly different: • Victims of terrorist bombings (906) –Injury complexity were compared with 55,033 –Increased severity casualties of non-terror related –More body regions involved –Enhanced use of intensive care trauma. -

Blast Waves and Fragment Velocities of Erythritol Tetranitrate

Full Paper DOI: 10.1002/prep.201600073 Blast Waves and Fragment Velocities of Erythritol Tetranitrate Masahiro Tagawa,*[a] Reiko I. Hiyoshi,[a] Masaru Takeuchi,[a] and Kimiya Akita[a] Abstract: Erythritol tetranitrate (ETN) is a highly sensitive distances of 5 and 7 m (8.9 and 12.5 m kgÀ1/3, respectively), nitrate ester that has a molecular structure similar to nitro- as verified by the waveforms and high-speed camera glycerine and pentaerythritol tetranitrate (PETN). In this images. Previous TNT data for peak overpressure vs. scaled study, experiments detonating 175 g of ETN were repeated distance were used to calculate the TNT equivalents for the three times to measure blast waves 0.6 m above the experimental data, which revealed that ETN had a similar ground. TNT and PETN were also tested under the same value to PETN. The fragment velocities of steel cylinders conditions for comparison. The average peak overpressure were measured, and that of ETN (1040 msÀ1) was higher of ETN was about 30 kPa at 3 m from the explosion center than that of TNT (957 m sÀ1) and lower than that of PETN (5.4 mkgÀ1/3 scaled distance), which was much higher than (1260 msÀ1). The Gurney constant for each explosive was that of TNT (about 22 kPa) and similar to PETN. The effects obtained by using the initial fragment velocities. of the reflected wave from the ground appeared at greater Keywords: Erythritol tetranitrate · TNT equivalent · Mach reflection · Metal fragments · Gurney constant 1 Introduction Erythritol tetranitrate (ETN) (Figure 1) is a simple nitrate In the presented study, several hundred grams of ETN ester that was first prepared in 1949 by Stenhouse [1], al- was prepared and explosion experiments were conducted. -

On the Influence of the Ammonium Nitrate(V)

energies Article On the Influence of the Ammonium Nitrate(V) Provenance on Its Usefulness for the Manufacture of ANFO Type Explosives Andrzej Biessikirski 1,* , Łukasz Kuterasi ´nski 2 , Michał Dworzak 1, Michał Twardosz 1, Maciej Tatko 3 and Bogna Daria Napruszewska 2 1 Faculty of Mining and Geoengineering, AGH University of Science and Technology, Al. Mickiewicza 30, 30-059 Kraków, Poland; [email protected] (M.D.); [email protected] (M.T.) 2 Jerzy Haber Institute of Catalysis and Surface Chemistry, Polish Academy of Sciences, ul. Niezapominajek 8, 30-239 Kraków, Poland; [email protected] (Ł.K.); [email protected] (B.D.N.) 3 Fluorochemika Poland sp. z o.o., ul. Kwiatkowskiego 8, 33-101 Tarnów, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-12-617-20-70 Received: 15 August 2020; Accepted: 18 September 2020; Published: 21 September 2020 Abstract: Ammonium nitrate fuel oil (ANFO) samples based on fertilizer (AN-F) and ammonium nitrate porous prill (AN-PP) were studied. Tests were carried out using both a thermogravimetric analyzer and differential scanning calorimetry (TGA/DSC). Furthermore, the scanning electron microscopy analysis (SEM) of ammonium nitrate(V) (AN) concerning either their surface or cross-section was performed. Based on the SEM results, it was shown that the surface of AN-F grains was flat and slightly deformed, while the AN-PP surface was wrinkled and deformed. Furthermore, the various steps of thermogravimetric process exhibited continuous AN phase transition according to precise temperatures. From TGA analysis, a significant mass loss was found as a result of ANFO decomposition.