Redalyc.Early Knowledge of Antarctica's Vegetation: Expanding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antarctic Bryophyte Research—Current State and Future Directions

Bry. Div. Evo. 043 (1): 221–233 ISSN 2381-9677 (print edition) DIVERSITY & https://www.mapress.com/j/bde BRYOPHYTEEVOLUTION Copyright © 2021 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 2381-9685 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/bde.43.1.16 Antarctic bryophyte research—current state and future directions PAULO E.A.S. CÂMARA1, MicHELine CARVALHO-SILVA1 & MicHAEL STecH2,3 1Departamento de Botânica, Universidade de Brasília, Brazil UnB; �[email protected]; http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3944-996X �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2389-3804 2Naturalis Biodiversity Center, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, Netherlands; 3Leiden University, Leiden, Netherlands �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9804-0120 Abstract Botany is one of the oldest sciences done south of parallel 60 °S, although few professional botanists have dedicated themselves to investigating the Antarctic bryoflora. After the publications of liverwort and moss floras in 2000 and 2008, respectively, new species were described. Currently, the Antarctic bryoflora comprises 28 liverwort and 116 moss species. Furthermore, Antarctic bryology has entered a new phase characterized by the use of molecular tools, in particular DNA sequencing. Although the molecular studies of Antarctic bryophytes have focused exclusively on mosses, molecular data (fingerprinting data and/or DNA sequences) have already been published for 36 % of the Antarctic moss species. In this paper we review the current state of Antarctic bryological research, focusing on molecular studies and conservation, and discuss future questions of Antarctic bryology in the light of global challenges. Keywords: Antarctic flora, conservation, future challenges, molecular phylogenetics, phylogeography Introduction The Antarctic is the most pristine, but also most extreme region on Earth in terms of environmental conditions. -

Carrivickice-Stream Initiation .Pdf

promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ This is an author produced version of a paper published in Quaternary Science Reviews. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/77904/ Paper: Glasser, NF, Davies, BJ, Carrivick, JL, Rodés, A, Hambrey, MJ, Smellie, JL and Domack, E (2014) Ice-stream initiation, duration and thinning on James Ross Island, northern Antarctic Peninsula. Quaternary Science Reviews, 86. 78 - 88. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.11.012 White Rose Research Online [email protected] *Manuscript Click here to view linked References 1 Ice-stream initiation, duration and thinning on James Ross Island, northern 2 Antarctic Peninsula 3 4 N.F. Glasser1†, B.J. Davies1, J.L. Carrivick2, A. Rodes3, M.J. Hambrey1, J.L. Smellie4, 5 E. Domack5 6 1Department of Geography and Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University, Wales, 7 SY23 3DB, UK. 8 2School of Geography, University of Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK 9 3SUERC, East Kilbride, UK 10 4Department of Geology, University of Leicester, University Road, Leicester LE1 11 7RH, UK 12 5Department of Geosciences, Hamilton College, Clinton, New York 13323, USA 13 †Email: [email protected] 14 15 ABSTRACT 16 Predicting the future response of the Antarctic Ice Sheet to climate change requires 17 an understanding of the ice streams that dominate its dynamics. Here we use 18 cosmogenic isotope exposure-age dating (26Al, 10Be and 36Cl) of erratic boulders on 19 ice-free land on James Ross Island, north-eastern Antarctic Peninsula, to define the 20 evolution of Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) ice in the adjacent Prince Gustav Channel. -

Management Plan for Antarctic Specially Protected Area No. 116 NEW COLLEGE VALLEY, CAUGHLEY BEACH, CAPE BIRD, ROSS ISLAND

Management Plan For Antarctic Specially Protected Area No. 116 NEW COLLEGE VALLEY, CAUGHLEY BEACH, CAPE BIRD, ROSS ISLAND 1. Description of values to be protected In 1985, two areas at Cape Bird, Ross Island were designated as SSSI No. 10, Caughley Beach (Recommendation XIII-8 (1985)) and SPA No. 20, New College Valley (Recommendation XIII-12 (1985)), following proposals by New Zealand that these areas should be protected because they contained some of the richest stands of moss and associated microflora and fauna in the Ross Sea region of Antarctica. This is the only area on Ross Island where protection is specifically given to plant assemblages and associated ecosystems. At that time, SPA No. 20 was enclosed within SSSI No. 10, in order to provide more stringent access conditions to that part of the Area. In 2000, SSSI No. 10 was incorporated with SPA No. 20 by Measure 1 (2000), with the former area covered by SPA No. 20 becoming a Restricted Zone within the revised SPA No. 20. The boundaries of the Area were revised from the boundaries in the original recommendations, in view of improved mapping and to follow more closely the ridges enclosing the catchment of New College Valley. Caughley Beach itself was adjacent to, but never a part of, the original Area, and for this reason the entire Area was renamed as New College Valley, which was within both of the original sites. The Area was redesignated by Decision 1 (2002) as Antarctic Specially Protected Area (ASPA) No. 116 and a revised Management Plan was adopted through Measure 1 (2006). -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 78/Tuesday, April 23, 2019/Rules

Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 78 / Tuesday, April 23, 2019 / Rules and Regulations 16791 U.S.C. 3501 et seq., nor does it require Agricultural commodities, Pesticides SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The any special considerations under and pests, Reporting and recordkeeping Antarctic Conservation Act of 1978, as Executive Order 12898, entitled requirements. amended (‘‘ACA’’) (16 U.S.C. 2401, et ‘‘Federal Actions to Address Dated: April 12, 2019. seq.) implements the Protocol on Environmental Justice in Minority Environmental Protection to the Richard P. Keigwin, Jr., Populations and Low-Income Antarctic Treaty (‘‘the Protocol’’). Populations’’ (59 FR 7629, February 16, Director, Office of Pesticide Programs. Annex V contains provisions for the 1994). Therefore, 40 CFR chapter I is protection of specially designated areas Since tolerances and exemptions that amended as follows: specially managed areas and historic are established on the basis of a petition sites and monuments. Section 2405 of under FFDCA section 408(d), such as PART 180—[AMENDED] title 16 of the ACA directs the Director the tolerance exemption in this action, of the National Science Foundation to ■ do not require the issuance of a 1. The authority citation for part 180 issue such regulations as are necessary proposed rule, the requirements of the continues to read as follows: and appropriate to implement Annex V Regulatory Flexibility Act (5 U.S.C. 601 Authority: 21 U.S.C. 321(q), 346a and 371. to the Protocol. et seq.) do not apply. ■ 2. Add § 180.1365 to subpart D to read The Antarctic Treaty Parties, which This action directly regulates growers, as follows: includes the United States, periodically food processors, food handlers, and food adopt measures to establish, consolidate retailers, not States or tribes. -

Joseph Hooker Takes a "Fixed Post": Transmutation And

Joseph Hooker Takes a "Fixed Post": Transmutation and the "Present Unsatisfactory State of Systematic Botany", 1844-1860 Author(s): Richard Bellon Source: Journal of the History of Biology, Vol. 39, No. 1 (Spring, 2006), pp. 1-39 Published by: Springer Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4331989 Accessed: 24-05-2018 19:09 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the History of Biology This content downloaded from 206.253.207.235 on Thu, 24 May 2018 19:09:40 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Journal of the History of Biology (2006) 39: 1-39 ? Springer 2006 DOI 10.007/sI 0739-004-3800-x Joseph Hooker Takes a "Fixed Post": Transmutation and the "Present Unsatisfactory State of Systematic Botany", 18 441860 RICHARD BELLON Lyman Briggs School Michigan State University E-30 Holmes Hall East Lansing, MI 48825 USA E-mail: hellonr(@.~msu.edu Abstract. Joseph Hooker first learned that Charles Darwin believed in the transmuta- tion of species in 1844. For the next 14 years, Hooker remained a "nonconsenter" to Darwin's views, resolving to keep the question of species origin "subservient to Botany instead of Botany to it, as must be the true relation." Hooker placed particular emphasis on the need for any theory of species origin to support the broad taxonomic delimitation of species, a highly contentious issue. -

BAS Science Summaries 2018-2019 Antarctic Field Season

BAS Science Summaries 2018-2019 Antarctic field season BAS Science Summaries 2018-2019 Antarctic field season Introduction This booklet contains the project summaries of field, station and ship-based science that the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) is supporting during the forthcoming 2018/19 Antarctic field season. I think it demonstrates once again the breadth and scale of the science that BAS undertakes and supports. For more detailed information about individual projects please contact the Principal Investigators. There is no doubt that 2018/19 is another challenging field season, and it’s one in which the key focus is on the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) and how this has changed in the past, and may change in the future. Three projects, all logistically big in their scale, are BEAMISH, Thwaites and WACSWAIN. They will advance our understanding of the fragility and complexity of the WAIS and how the ice sheets are responding to environmental change, and contributing to global sea-level rise. Please note that only the PIs and field personnel have been listed in this document. PIs appear in capitals and in brackets if they are not present on site, and Field Guides are indicated with an asterisk. Non-BAS personnel are shown in blue. A full list of non-BAS personnel and their affiliated organisations is shown in the Appendix. My thanks to the authors for their contributions, to MAGIC for the field sites map, and to Elaine Fitzcharles and Ali Massey for collating all the material together. Thanks also to members of the Communications Team for the editing and production of this handy summary. -

Bibliography of Publications 1974 – 2019

W. SZAFER INSTITUTE OF BOTANY POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Ryszard Ochyra BIBLIOGRAPHY OF PUBLICATIONS 1974 – 2019 KRAKÓW 2019 Ochyraea tatrensis Váňa Part I. Monographs, Books and Scientific Papers Part I. Monographs, Books and Scientific Papers 5 1974 001. Ochyra, R. (1974): Notatki florystyczne z południowo‑wschodniej części Kotliny Sandomierskiej [Floristic notes from southeastern part of Kotlina Sandomierska]. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego 360 Prace Botaniczne 2: 161–173 [in Polish with English summary]. 002. Karczmarz, K., J. Mickiewicz & R. Ochyra (1974): Musci Europaei Orientalis Exsiccati. Fasciculus III, Nr 101–150. 12 pp. Privately published, Lublini. 1975 003. Karczmarz, K., J. Mickiewicz & R. Ochyra (1975): Musci Europaei Orientalis Exsiccati. Fasciculus IV, Nr 151–200. 13 pp. Privately published, Lublini. 004. Karczmarz, K., K. Jędrzejko & R. Ochyra (1975): Musci Europaei Orientalis Exs‑ iccati. Fasciculus V, Nr 201–250. 13 pp. Privately published, Lublini. 005. Karczmarz, K., H. Mamczarz & R. Ochyra (1975): Hepaticae Europae Orientalis Exsiccatae. Fasciculus III, Nr 61–90. 8 pp. Privately published, Lublini. 1976 006. Ochyra, R. (1976): Materiały do brioflory południowej Polski [Materials to the bry‑ oflora of southern Poland]. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego 432 Prace Botaniczne 4: 107–125 [in Polish with English summary]. 007. Ochyra, R. (1976): Taxonomic position and geographical distribution of Isoptery‑ giopsis muelleriana (Schimp.) Iwats. Fragmenta Floristica et Geobotanica 22: 129–135 + 1 map as insertion [with Polish summary]. 008. Karczmarz, K., A. Łuczycka & R. Ochyra (1976): Materiały do flory ramienic środkowej i południowej Polski. 2 [A contribution to the flora of Charophyta of central and southern Poland. 2]. Acta Hydrobiologica 18: 193–200 [in Polish with English summary]. -

John Hooper - Pioneer British Batman

NEWSLETTER AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE LINNEAN SOCIETY OF LONDON VOLUME 26 x NUMBER xJULY 2010 THE LINNEAN SOCIETY OF LONDON Registered Charity Number 220509 Burlington House, Piccadilly, London W1J 0BF Tel. (+44) (0)20 7434 4479; Fax: (+44) (0)20 7287 9364 e-mail: [email protected]; internet: www.linnean.org President Secretaries Council Dr Vaughan Southgate BOTANICAL The Officers and Dr Sandra D Knapp Prof Geoffrey Boxshall Vice-Presidents Prof Mark Chase Dr Mike Fay ZOOLOGICAL Prof Dianne Edwards Dr Sandra D Knapp Dr Malcolm Scoble Mr Alistair Land Dr Keith Maybury Dr Terry Langford Dr Malcolm Scoble EDITORIAL Mr Brian Livingstone Dr John R Edmondson Prof Geoff Moore Treasurer Ms Sara Oldfield Professor Gren Ll Lucas OBE COLLECTIONS Dr Sylvia Phillips Mrs Susan Gove Mr Terence Preston Executive Secretary Dr Mark Watson Dr Ruth Temple Librarian Dr David Williams Mrs Lynda Brooks Prof Patricia Willmer Financial Controller/Membership Mr Priya Nithianandan Deputy Librarian Conservator Mr Ben Sherwood Ms Janet Ashdown Building and Office Manager Ms Victoria Smith Honorary Archivist Conservation Assistant Ms Gina Douglas Ms Lucy Gosnay Communications Manager Ms Claire Inman Special Publications and Education Manager Ms Leonie Berwick Office Assistant Mr Tom Helps THE LINNEAN Newsletter and Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London ISSN 0950-1096 Edited by Brian G Gardiner Editorial ................................................................................................................ 1 Society News.............................................................................................................. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/06/2021 12:07:02PM Via Free Access 332 Th E Dream of the North Science, Technology, Progress, Urbanity, Industry, and Even Perfectibility

5. Th e Northern Heyday: 1830–1880 Tipping the Scales In Europe, the mid-nineteenth century witnessed a decisive change in the relative strength of North and South, confi rming a long-term trend that had been visible for a hundred years, and that had accelerated since the fall of Bonaparte. Great Britain was clearly the main driving force behind this development, but by no means the only one. Such key statistical indicators as population growth and GDP show an unquestionable strengthening in several of the northern nations. A comparison between, for instance, Britain, Germany and the Nordic countries, on the one hand, and France, Spain and Italy, on the other, shows that in 1830, the population of the former group was signifi cantly lower than that of the latter, i.e. 58 vs. 67 million.1 By 1880, the balance had shifted decisively in favour of the North, with 90 vs. 82 million. With regard to GDP, the trend is even more explicit. Available estimates from 1820 show that the above group of northern countries together had a GDP of approximately 67 billion dollars, as compared to 69 billion for the southern countries. In 1870, the GDP of the South had risen to 132 billion (a 91 percent increase), but that of the North to 187 billion (179 percent increase).2 During the 1830–1880 period, the Russian population similarly grew from 56 to 98 million, representing by far the biggest nation in the West, whereas the United States was rapidly climbing from only 13 to 50 million, and Canada from 1 to 4 million (“Population Statistics”, 2006). -

Public Information Leaflet HISTORY.Indd

British Antarctic Survey History The United Kingdom has a long and distinguished record of scientific exploration in Antarctica. Before the creation of the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), there were many surveying and scientific expeditions that laid the foundations for modern polar science. These ranged from Captain Cook’s naval voyages of the 18th century, to the famous expeditions led by Scott and Shackleton, to a secret wartime operation to secure British interests in Antarctica. Today, BAS is a world leader in polar science, maintaining the UK’s long history of Antarctic discovery and scientific endeavour. The early years Britain’s interests in Antarctica started with the first circumnavigation of the Antarctic continent by Captain James Cook during his voyage of 1772-75. Cook sailed his two ships, HMS Resolution and HMS Adventure, into the pack ice reaching as far as 71°10' south and crossing the Antarctic Circle for the first time. He discovered South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands although he did not set eyes on the Antarctic continent itself. His reports of fur seals led many sealers from Britain and the United States to head to the Antarctic to begin a long and unsustainable exploitation of the Southern Ocean. Image: Unloading cargo for the construction of ‘Base A’ on Goudier Island, Antarctic Peninsula (1944). During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, interest in Antarctica was largely focused on the exploitation of its surrounding waters by sealers and whalers. The discovery of the South Shetland Islands is attributed to Captain William Smith who was blown off course when sailing around Cape Horn in 1819. -

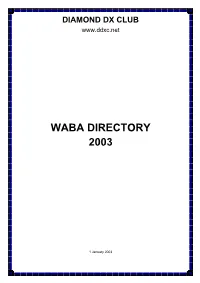

Waba Directory 2003

DIAMOND DX CLUB www.ddxc.net WABA DIRECTORY 2003 1 January 2003 DIAMOND DX CLUB WABA DIRECTORY 2003 ARGENTINA LU-01 Alférez de Navió José María Sobral Base (Army)1 Filchner Ice Shelf 81°04 S 40°31 W AN-016 LU-02 Almirante Brown Station (IAA)2 Coughtrey Peninsula, Paradise Harbour, 64°53 S 62°53 W AN-016 Danco Coast, Graham Land (West), Antarctic Peninsula LU-19 Byers Camp (IAA) Byers Peninsula, Livingston Island, South 62°39 S 61°00 W AN-010 Shetland Islands LU-04 Decepción Detachment (Navy)3 Primero de Mayo Bay, Port Foster, 62°59 S 60°43 W AN-010 Deception Island, South Shetland Islands LU-07 Ellsworth Station4 Filchner Ice Shelf 77°38 S 41°08 W AN-016 LU-06 Esperanza Base (Army)5 Seal Point, Hope Bay, Trinity Peninsula 63°24 S 56°59 W AN-016 (Antarctic Peninsula) LU- Francisco de Gurruchaga Refuge (Navy)6 Harmony Cove, Nelson Island, South 62°18 S 59°13 W AN-010 Shetland Islands LU-10 General Manuel Belgrano Base (Army)7 Filchner Ice Shelf 77°46 S 38°11 W AN-016 LU-08 General Manuel Belgrano II Base (Army)8 Bertrab Nunatak, Vahsel Bay, Luitpold 77°52 S 34°37 W AN-016 Coast, Coats Land LU-09 General Manuel Belgrano III Base (Army)9 Berkner Island, Filchner-Ronne Ice 77°34 S 45°59 W AN-014 Shelves LU-11 General San Martín Base (Army)10 Barry Island in Marguerite Bay, along 68°07 S 67°06 W AN-016 Fallières Coast of Graham Land (West), Antarctic Peninsula LU-21 Groussac Refuge (Navy)11 Petermann Island, off Graham Coast of 65°11 S 64°10 W AN-006 Graham Land (West); Antarctic Peninsula LU-05 Melchior Detachment (Navy)12 Isla Observatorio -

Darwin's Botanical Arithmetic and the "Principle of Divergence," 1854-1858

Darwin's Botanical Arithmetic and the Principle of Divergence, 1854-1858 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Browne, Janet. 1980. Darwin's botanical arithmetic and the principle of divergence, 1854-1858. Journal of the History of Biology 13(1): 53-89. Published Version http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00125354 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:3372262 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Darwin'sBotanical Arithmetic and the "Principle of Divergence,"1854-1858 JANET BROWNE Department of the History of Science Imperial College Exhibition Road London SW7 2AZ, England The story of Charles Darwin's intellectual development during the years 1837 to 1859 is the most famous and extensively documented story in the history of biology. Yet despite continued interest in Dar- win's papers, there are many problems and novel topics still to be explored that will indubitablyadd to such an account. It is the purpose of this paper to describe a little-known aspect of Darwin'sresearches during the pre-Originperiod and to place this in the largerframe of his developing theories. The subject is what was then known as "botanical arithmetic"and its object, so far as Darwinwas concerned,was to dis- cover quantitative rules for the appearanceof varietiesin nature.These arithmeticalexercises supplied the context in which Darwindiscovered his "principle of divergence."I propose that Darwin'sbotanical arith- metic also provided a great deal of the content of that principle,or, to speak more precisely,provided the informationthat disclosed problems which could only be solved by the intervention of an extra "force" in evolutionary theory.