Carrivickice-Stream Initiation .Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 78/Tuesday, April 23, 2019/Rules

Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 78 / Tuesday, April 23, 2019 / Rules and Regulations 16791 U.S.C. 3501 et seq., nor does it require Agricultural commodities, Pesticides SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The any special considerations under and pests, Reporting and recordkeeping Antarctic Conservation Act of 1978, as Executive Order 12898, entitled requirements. amended (‘‘ACA’’) (16 U.S.C. 2401, et ‘‘Federal Actions to Address Dated: April 12, 2019. seq.) implements the Protocol on Environmental Justice in Minority Environmental Protection to the Richard P. Keigwin, Jr., Populations and Low-Income Antarctic Treaty (‘‘the Protocol’’). Populations’’ (59 FR 7629, February 16, Director, Office of Pesticide Programs. Annex V contains provisions for the 1994). Therefore, 40 CFR chapter I is protection of specially designated areas Since tolerances and exemptions that amended as follows: specially managed areas and historic are established on the basis of a petition sites and monuments. Section 2405 of under FFDCA section 408(d), such as PART 180—[AMENDED] title 16 of the ACA directs the Director the tolerance exemption in this action, of the National Science Foundation to ■ do not require the issuance of a 1. The authority citation for part 180 issue such regulations as are necessary proposed rule, the requirements of the continues to read as follows: and appropriate to implement Annex V Regulatory Flexibility Act (5 U.S.C. 601 Authority: 21 U.S.C. 321(q), 346a and 371. to the Protocol. et seq.) do not apply. ■ 2. Add § 180.1365 to subpart D to read The Antarctic Treaty Parties, which This action directly regulates growers, as follows: includes the United States, periodically food processors, food handlers, and food adopt measures to establish, consolidate retailers, not States or tribes. -

BAS Science Summaries 2018-2019 Antarctic Field Season

BAS Science Summaries 2018-2019 Antarctic field season BAS Science Summaries 2018-2019 Antarctic field season Introduction This booklet contains the project summaries of field, station and ship-based science that the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) is supporting during the forthcoming 2018/19 Antarctic field season. I think it demonstrates once again the breadth and scale of the science that BAS undertakes and supports. For more detailed information about individual projects please contact the Principal Investigators. There is no doubt that 2018/19 is another challenging field season, and it’s one in which the key focus is on the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) and how this has changed in the past, and may change in the future. Three projects, all logistically big in their scale, are BEAMISH, Thwaites and WACSWAIN. They will advance our understanding of the fragility and complexity of the WAIS and how the ice sheets are responding to environmental change, and contributing to global sea-level rise. Please note that only the PIs and field personnel have been listed in this document. PIs appear in capitals and in brackets if they are not present on site, and Field Guides are indicated with an asterisk. Non-BAS personnel are shown in blue. A full list of non-BAS personnel and their affiliated organisations is shown in the Appendix. My thanks to the authors for their contributions, to MAGIC for the field sites map, and to Elaine Fitzcharles and Ali Massey for collating all the material together. Thanks also to members of the Communications Team for the editing and production of this handy summary. -

Public Information Leaflet HISTORY.Indd

British Antarctic Survey History The United Kingdom has a long and distinguished record of scientific exploration in Antarctica. Before the creation of the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), there were many surveying and scientific expeditions that laid the foundations for modern polar science. These ranged from Captain Cook’s naval voyages of the 18th century, to the famous expeditions led by Scott and Shackleton, to a secret wartime operation to secure British interests in Antarctica. Today, BAS is a world leader in polar science, maintaining the UK’s long history of Antarctic discovery and scientific endeavour. The early years Britain’s interests in Antarctica started with the first circumnavigation of the Antarctic continent by Captain James Cook during his voyage of 1772-75. Cook sailed his two ships, HMS Resolution and HMS Adventure, into the pack ice reaching as far as 71°10' south and crossing the Antarctic Circle for the first time. He discovered South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands although he did not set eyes on the Antarctic continent itself. His reports of fur seals led many sealers from Britain and the United States to head to the Antarctic to begin a long and unsustainable exploitation of the Southern Ocean. Image: Unloading cargo for the construction of ‘Base A’ on Goudier Island, Antarctic Peninsula (1944). During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, interest in Antarctica was largely focused on the exploitation of its surrounding waters by sealers and whalers. The discovery of the South Shetland Islands is attributed to Captain William Smith who was blown off course when sailing around Cape Horn in 1819. -

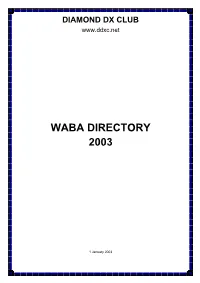

Waba Directory 2003

DIAMOND DX CLUB www.ddxc.net WABA DIRECTORY 2003 1 January 2003 DIAMOND DX CLUB WABA DIRECTORY 2003 ARGENTINA LU-01 Alférez de Navió José María Sobral Base (Army)1 Filchner Ice Shelf 81°04 S 40°31 W AN-016 LU-02 Almirante Brown Station (IAA)2 Coughtrey Peninsula, Paradise Harbour, 64°53 S 62°53 W AN-016 Danco Coast, Graham Land (West), Antarctic Peninsula LU-19 Byers Camp (IAA) Byers Peninsula, Livingston Island, South 62°39 S 61°00 W AN-010 Shetland Islands LU-04 Decepción Detachment (Navy)3 Primero de Mayo Bay, Port Foster, 62°59 S 60°43 W AN-010 Deception Island, South Shetland Islands LU-07 Ellsworth Station4 Filchner Ice Shelf 77°38 S 41°08 W AN-016 LU-06 Esperanza Base (Army)5 Seal Point, Hope Bay, Trinity Peninsula 63°24 S 56°59 W AN-016 (Antarctic Peninsula) LU- Francisco de Gurruchaga Refuge (Navy)6 Harmony Cove, Nelson Island, South 62°18 S 59°13 W AN-010 Shetland Islands LU-10 General Manuel Belgrano Base (Army)7 Filchner Ice Shelf 77°46 S 38°11 W AN-016 LU-08 General Manuel Belgrano II Base (Army)8 Bertrab Nunatak, Vahsel Bay, Luitpold 77°52 S 34°37 W AN-016 Coast, Coats Land LU-09 General Manuel Belgrano III Base (Army)9 Berkner Island, Filchner-Ronne Ice 77°34 S 45°59 W AN-014 Shelves LU-11 General San Martín Base (Army)10 Barry Island in Marguerite Bay, along 68°07 S 67°06 W AN-016 Fallières Coast of Graham Land (West), Antarctic Peninsula LU-21 Groussac Refuge (Navy)11 Petermann Island, off Graham Coast of 65°11 S 64°10 W AN-006 Graham Land (West); Antarctic Peninsula LU-05 Melchior Detachment (Navy)12 Isla Observatorio -

Short Note Late Ordovician–Silurian Orthoconic Nautiloid Cephalopods in the View Point Formation Conglomerate, Antarctic Peninsula ALAN P.M

Antarctic Science 24(6), 635–636 (2012) & Antarctic Science Ltd 2012 doi:10.1017/S095410201200065X Short Note Late Ordovician–Silurian orthoconic nautiloid cephalopods in the View Point Formation conglomerate, Antarctic Peninsula ALAN P.M. VAUGHAN1, CHARLES H. HOLLAND2, JOHN D. BRADSHAW3 and MICHAEL R.A. THOMSON4 1British Antarctic Survey, NERC, High Cross, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0ET, UK 2Department of Geology, Trinity College, Dublin 2, Ireland 3Department of Geological Sciences, University of Canterbury, Private Bag 4800, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand 4Centre for Polar Sciences, School of Earth Sciences, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK [email protected] Received 12 April 2012, accepted 11 July 2012, first published online 13 August 2012 Introduction preserved diameter of about 9 x 10 mm (Fig. 2a). A convex septal surface is preserved at the adapical end with depth of The Trinity Peninsula Group at View Point, northern Antarctic 0.5 mm (Fig. 2b). A very small siphuncle, only about 1 mm Peninsula comprises a succession of thin sandstone-mudstone in diameter, is seen approximately centrally (Fig. 2b). couplets of probably turbidity current origin (Bradshaw et al. 2012). This succession, which is southward younging and overturned, hosts 100 m-thick sequences of lenticular Interpretation sandstone bodies, at least ten of which include pebble to In the absence of information on ornamentation or internal boulder conglomerates up to 15 m thick. The deposits structure, both of which figure so prominently in nautiloid are probably of submarine fan origin and it is thought that taxonomy, it is difficult to identify this material, but it is the thick lenticular sequences (with boulders up to 1.3 m) reasonable to suppose that the two specimens represent the are derived from contemporary or slightly older Permo- same taxon. -

CLIVAR/Clic/SCAR Southern Ocean Region Panel SORP National

CLIVAR/CliC/SCAR Southern Ocean Region Panel SORP National activities report Country__BELGIUM______________________________ Contributor(s) (writer(s)) __François Massonnet________________ Date__February 1st, 2019_________________ Receipt of material prior to 1 February 2019 will ensure inclusion discussions at the first SORP video conference for 2019. The reports contribute to future SORP discussions, as well as input to the SOOS and other CLIVAR/CliC/SCAR activities. All reports will be posted on the SORP website. Purpose of material gathered for the SORP: To build an overview of observational, modeling, national projects and initiatives, ocean reanalysis and state estimation initiatives relevant to the SORP (This can be detailed as a list of activities; maps showing where instruments have been or will be deployed; examples of modeling developments, experiments and set-ups; major national and international project involvement; etc.) Please refer to SORP’s terms of reference (also given at the end of this template) for guidance on scope: http://www.clivar.org/clivar-panels/southern Note: Biological topics such as marine ecology research, for example, are not within the scope of SORP’s terms of reference and are therefore not required in these reports. However, SOOS has an interest in such research, so National Representatives are encouraged to include summaries of such research as separate sections. Note: The Southern Ocean is not explicitly defined in SORP’s terms of reference, so please note what the limit used for your national report is (e.g., research on regions only beyond an oceanographic boundary like “south of the Polar Front”, or research contained within latitudinal limits like “south of 50°S”). -

Configuration of the Northern Antarctic Peninsula Ice Sheet at LGM Based on a New Synthesis of Seabed Imagery

The Cryosphere, 9, 613–629, 2015 www.the-cryosphere.net/9/613/2015/ doi:10.5194/tc-9-613-2015 © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Configuration of the Northern Antarctic Peninsula Ice Sheet at LGM based on a new synthesis of seabed imagery C. Lavoie1,2, E. W. Domack3, E. C. Pettit4, T. A. Scambos5, R. D. Larter6, H.-W. Schenke7, K. C. Yoo8, J. Gutt7, J. Wellner9, M. Canals10, J. B. Anderson11, and D. Amblas10 1Istituto Nazionale di Oceanografia e di Geofisica Sperimentale (OGS), Borgo Grotta Gigante, Sgonico, 34010, Italy 2Department of Geosciences/CESAM, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, 3810-193, Portugal 3College of Marine Science, University of South Florida, St. Petersburg, Florida 33701, USA 4Department of Geosciences, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, Alaska 99775, USA 5National Snow and Ice Data Center, University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado 80309, USA 6British Antarctic Survey, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, CB3 0ET, UK 7Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven, 27568, Germany 8Korean Polar Research Institute, Incheon, 406-840, Republic of Korea 9Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Houston, Houston, Texas 77204, USA 10Departament d’Estratigrafia, Paleontologia i Geociències Marines/GRR Marine Geosciences, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona 08028, Spain 11Department of Earth Science, Rice University, Houston, Texas 77251, USA Correspondence to: C. Lavoie ([email protected]) or E. W. Domack ([email protected]) Received: 13 September 2014 – Published in The Cryosphere Discuss.: 15 October 2014 Revised: 18 February 2015 – Accepted: 9 March 2015 – Published: 1 April 2015 Abstract. We present a new seafloor map for the northern centered on the continental shelf at LGM. -

Questions to Ask Before Selecting Your Travel Company Cover Photo: © Ralph Lee Hopkins

ANTARCTICA A HOW-TO GUIDE TO A SAFE & REWARDING ANTARCTICA EXPERIENCE 6 Questions to ask before selecting your travel company Cover photo: © Ralph Lee Hopkins. Above: © Andrew Peacock. here are many, many reasons to want to visit Antarctica: the dashing history of the Heroic Age of exploration; the penguins; the majestic icebergs and glaciers; the breathtaking mountains surging 9,000 feet straight up from the sea; the ability to breathe in some of the most pristine air on the planet; or the profound absence of anything man-made. TAntarctica is a place of extraordinary natural beauty that calls to many travelers. It is one of the world’s last great wildernesses, providing travelers with the opportunity to experience genuine pristine wildness. And it is inarguably threatened by climate change, providing an urgent mission for many to view this increasingly vulnerable ecosystem. However, the risks, inherent in any travel, of bringing guests to a remote and fickle environment are magnified in Antarctica, because there are potential perils and fewer rescue resources for vessels in trouble. Over the last several years, safety has become an increasingly important component of any discussion on Antarctica since many more travel companies are sending ships there. A century ago, visiting Antarctica was only possible for explorers and scientists. The first vessel specifically built for the purpose of taking ‘citizen explorers’ to Antarctica was the ice-strengthened Lindblad Explorer launched in 1969. She paved the way for travelers to experience the world’s last unspoiled continent by means of “expedition cruising”—defined by the industry as cruising coupled with education as a major theme. -

Trinity Peninsula Group (Permo-Triassic?) at Hope Bay, Antarctic Peninsula

POLISH POLAR RESEARCH 13 3-4 215-240 1992 Krzysztof BIRKENMAJER Institute of Geological Sciences Polish Academy of Sciences Senacka 1 — 3 31-002 Kraków, POLAND Trinity Peninsula Group (Permo-Triassic?) at Hope Bay, Antarctic Peninsula ABSTRACT: The Trinity Peninsula Group (Permo-Triassic?) at Hope Bay, northern Antarctic Peninsula, is represented by the Hope Bay Formation, more than 1200 m thick. It is subdivided into three members: the Hut Cove Member (HBF,), more than 500 m thick (base unknown), is a generally unfossiliferous marine turbidite unit formed under anaerobic to dysaerobic conditions, with trace fossils only in its upper part; the Seal Point Member (HBF2), 170—200 m thick, is a marine turbidite unit formed under dysaerobic conditions, with trace fossils and allochthonous plant detritus; the Scar Hills Member (HBF3), more than 550 m thick (top unknown), is a predominantly sandstone unit rich in plant detritus, probably formed under deltaic conditions. The supply of clastic material was from northeastern sources. The Hope Bay Formation was folded prior to Middle Jurassic terrestrial plant-bearing beds (Mount Flora Formation), from which it is separated by angular unconformity. Acidic porphyritic dykes and sills cut through the Hope Bay Formation. They were probably feeders for terrestrial volcanics of the Kenney Glacier Formation (Lower Cretaceous) which unconformably covers the Mount Flora Formation. Andean-type diorite and gabbro plutons and dykes (Cretaceous) intrude the Hope Bay Formation, causing thermal alteration of its deposits in a zone up to several hundred metres thick. All the above units are displaced by two system of faults, an older longitudinal, and a younger transversal, of late Cretaceous or Tertiary age. -

Revised List of Historic Sites and Monuments

Measure 19 (2015) Annex Revised List of Historic Sites and Monuments Designation/ No. Description Location Amendment 1. Flag mast erected in December 1965 at the South Geographical Pole by the First Argentine Overland Polar 90S Rec. VII-9 Expedition. Original proposing Party: Argentina Party undertaking management: Argentina 2. Rock cairn and plaques at Syowa Station in memory of Shin Fukushima, a member of the 4th Japanese 6900'S, Rec. VII-9 Antarctic Research Expedition, who died in October 1960 while performing official duties. The cairn was 3935'E erected on 11 January 1961, by his colleagues. Some of his ashes repose in the cairn. Original proposing Party: Japan Party undertaking management: Japan 3. Rock cairn and plaque on Proclamation Island, Enderby Land, erected in January 1930 by Sir Douglas 6551'S, Rec.VII-9 Mawson. The cairn and plaque commemorate the landing on Proclamation Island of Sir Douglas 5341'E Mawson with a party from the British, Australian and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition of 1929-31. Original proposing Party: Australia Party undertaking management: Australia 4. Pole of Inaccessibility Station building. Station building to which a bust of V.I. Lenin is fixed, together 82°06'42”S, Rec. VII-9 with a plaque in memory of the conquest of the Pole of Inaccessibility by Soviet Antarctic explorers in 55°01'57”E Measure 11(2012) 1958. As of 2007 the station building was covered by snow. The bust of Lenin is erected on the wooden stand mounted on the building roof at about 1.5 m high above the snow surface. -

High Resolution Spatial Mapping of Human Footprint Across Antarctica and Its Implications for the Strategic Conservation of Avifauna

RESEARCH ARTICLE High Resolution Spatial Mapping of Human Footprint across Antarctica and Its Implications for the Strategic Conservation of Avifauna Luis R. Pertierra1*, Kevin A. Hughes2, Greta C. Vega1, Miguel A . Olalla-TaÂrraga1 1 Area de Biodiversidad y ConservacioÂn, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, MoÂstoles, Spain, 2 British Antarctic Survey, National Environment Research Council, High Cross, Madingley Road, Cambridge, United Kingdom a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Human footprint models allow visualization of human spatial pressure across the globe. Up until now, Antarctica has been omitted from global footprint models, due possibly to the lack of a permanent human population and poor accessibility to necessary datasets. Yet Antarc- OPEN ACCESS tic ecosystems face increasing cumulative impacts from the expanding tourism industry Citation: Pertierra LR, Hughes KA, Vega GC, Olalla- and national Antarctic operator activities, the management of which could be improved with  TaÂrraga MA (2017) High Resolution Spatial footprint assessment tools. Moreover, Antarctic ecosystem dynamics could be modelled to Mapping of Human Footprint across Antarctica and Its Implications for the Strategic Conservation incorporate human drivers. Here we present the first model of estimated human footprint of Avifauna. PLoS ONE 12(1): e0168280. across predominantly ice-free areas of Antarctica. To facilitate integration into global mod- doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0168280 els, the Antarctic model was created using methodologies applied elsewhere with land use, Editor: Hans-Ulrich Peter, Friedrich-Schiller- density and accessibility features incorporated. Results showed that human pressure is Universitat Jena, GERMANY clustered predominantly in the Antarctic Peninsula, southern Victoria Land and several Received: September 13, 2016 areas of East Antarctica. -

Avanço E Retração De Área Glacial No Extremo Norte Da Península Trinity, Antártica, Entre 1988 E 2015

Revista do Departamento de Geografia Universidade de São Paulo www.revistas.usp.br/rdg ISSN 2236-2878 V.31 (2016) AVANÇO E RETRAÇÃO DE ÁREA GLACIAL NO EXTREMO NORTE DA PENÍNSULA TRINITY, ANTÁRTICA, ENTRE 1988 E 2015 ADVANCE AND RETREAT OF GLACIERS IN THE NORTHERN TIP OF THE TRINITY PENINSULA, ANTARCTICA, 1988-2015 Maria Eliza Sotille Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul [email protected] Ulisses Franz Bremer Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul Jefferson Cardia Simões Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul Recebido (Received): 22/09/2015 Aceito (Accepted): 27/01/2016 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.11606/rdg.v31i0.104513 Resumo: O extremo norte da Península Trinity, na Abstract: The north tip of the Trinity Peninsula, Antarctic Península Antártica, sofreu mudanças na sua área coberta Peninsula, has undergone changes in its ice-covered area de gelo e na temperatura do ar ao longo das últimas três and in the air temperature over the last three decades. décadas. Visando apontar os avanços e as retrações da Aiming to identify ice mass advances and retractions that massa de gelo ocorridas na área, realizamos um occurred in the area, we conducted a survey of the levantamento das variações da posição das frentes de 32 changes in the ice front positions of 32 glaciers over 27 geleiras ao longo de 27 anos (1988–2015). O estudo usou years (1988-2015). The study used 10 Landsat images to 10 imagens Landsat para identificar as variações das identify variations of glaciers fronts and compare them frentes das geleiras e compará-las com as variações na with variations in the mean annual air temperature.