History As a System of Wrongs — Examining South Africa's Marikana Tragedy in a Temporal Legal Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country Guide South Africa

Human Rights and Business Country Guide South Africa March 2015 Table of Contents How to Use this Guide .................................................................................. 3 Background & Context ................................................................................. 7 Rights Holders at Risk ........................................................................... 15 Rights Holders at Risk in the Workplace ..................................................... 15 Rights Holders at Risk in the Community ................................................... 25 Labour Standards ................................................................................. 35 Child Labour ............................................................................................... 35 Forced Labour ............................................................................................ 39 Occupational Health & Safety .................................................................... 42 Trade Unions .............................................................................................. 49 Working Conditions .................................................................................... 56 Community Impacts ............................................................................. 64 Environment ............................................................................................... 64 Land & Property ......................................................................................... 72 Revenue Transparency -

Black South African History Pdf

Black south african history pdf Continue In South African history, this article may require cleaning up in accordance with Wikipedia quality standards. The specific problem is to reduce the overall quality, especially the lead section. Please help improve this article if you can. (June 2019) (Find out how and when to remove this message template) Part of the series on the history of the weapons of the South African Precolonial Middle Stone Age Late Stone Age Bantu expansion kingdom mapungubwe Mutapa Kaditshwene Dutch colonization of the Dutch Cape Colony zulu Kingdom of Shaka kaSenzangakhona Dingane kaSenzangakhona Mpande kaSenzangakhona Cetshwayo kaMpande Dinuzulu kaCetshwayo 1887 Annexation (British) British Colonization Cape Colony Colonia Natal Transvaal Colony Orange River Colony Bur Republic South African Orange Free Republic Natalia Republic Bur War First Storm War Jameson Reid Second World War Union of South Africa First World War of apartheid Legislation South African Border War Angolan Civil War Bantustans Internal Resistance to apartheid referendum after apartheid Mandela Presidency Motlante Presidency of the Presidency of the President zuma The theme of economic history of invention and the opening of the Military History Political History Religious History Slavery Timeline South Africa portalv Part series on Culture History of South Africa People Languages Afrikaans English Ndebele North Soto Sowazi Swazi Tswana Tsonga Venda Xhosa Zulus Kitchens Festivals Public Holidays Religion Literature Writers Music And Performing Arts -

I Stand Corrected and Somnyama Ngonyama

PERFORMANCE PARADIGM 15 (2020) Aylwyn Walsh Poethics of Queer Resurrection in Black South African Performance: I Stand Corrected and Somnyama Ngonyama Mamela Nyamza’s long legs stick out from the dustbin, her torso inside. Her body is surrounded by black trash bags that are illuminated by light. Charlie, played by artist Mojisola Adebayo, spins the narrative that has led to this moment: she is due to be married that morning to her South African lover, Zodwa. While Adebayo’s character waits for her, goes searching for her, and entreats the South African police to help her find her, Zodwa’s body lies in the trash. Murdered, and discarded, like so many other women each year in this violent country. I Stand Corrected (2012-2014) is a performance created collaboratively by British/Nigerian writer/performer Adebayo and South African dancer/choreographer Nyamza.1 Adebayo is a well-known arts practitioner working internationally; and as a young person, Nyamza was taught ballet in a rare opportunity for people living in townships (Giovanni 2014). She is one of South Africa’s leading Black female dance professionals (until recently also artistic director of the South African Dance Umbrella at the State Theatre).2 Starting from the sad and infuriating statistics of an estimated 500,000 rapes a year in South Africa (Action Aid 2009), the work plays on a gruesome phrase: there is a growing trend for men (often groups of men) to rape lesbians to “correct” their sexual orientation. Action Aid reports that: a culture of rape is already being passed down to younger generations of South African men. -

Ernestine White-Mifetu

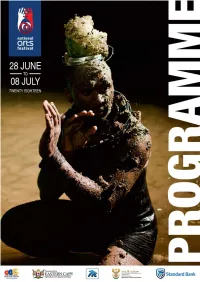

20 2018 Festival Curators Visual and Performance Art Ernestine White-Mifetu ERNESTINE WHITE-MIFETU is currently the curator of Contemporary Art at Iziko’s South African National Gallery. Her experience within the arts and culture sector spans a period of fifteen years. She holds a Bachelors degree in Fine Art (1999) cum CURATED PROGRAMME laude from the State University of Purchase College in New York, a Master Printer degree in Fine Art Lithography (2001) from the Tamarind Institute in New Mexico, a Masters degree in Fine Art (2004) from the Michaelis School of Fine Art, Cape Town, and a Honours degree in Curatorship (2013) from the University of Cape Town’s Michaelis School of Fine Art. Ms White-Mifetu obtained her initial curatorial experience working as the Exhibitions Coordinator (2004-2006) and thereafter as Senior Projects Coordinator for Parliament’s nation building initiative, the Parliamentary Millennium Programme. Prior to this she worked as the Collections Manager for Iziko’s South African National Gallery. As an independent artist her work can be found in major collections in South Africa as well as in the United States. Ernestine White’s most recent accomplishment was the inclusion of her artwork into permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art, US. Music Samson Diamond SAMSON DIAMOND is the appointed leader of the Odeion String Quartet at the University of the Free State and concertmaster of the Free State Symphony Orchestra (FSSO). He has appeared as violin soloist with all premier South African orchestras and has played principal second of Europe’s first black and ethnic minority orchestra, Chineke! Orchestra, since its inception. -

Massacre at Marikana

MASSACRE AT MARIKANA Michael Power & Manson Gwanyanya • A failure of oversight and the need • for direct community involvement ABSTRACT This paper assesses the findings of the Marikana Commission of Inquiry against Lonmin – the mining company at the centre of a wage dispute that led to the deaths of 34 protesting mineworkers in South Africa’s platinum belt – and the South African Department of Mineral Resources (DMR), particularly in relation to: (1) Lonmin’s failure to provide adequate housing to mineworkers; (2) DMR’s failure to exercise appropriate oversight over Lonmin; (3) how Lonmin and the DMR helped create an environment conducive to the massacre; and (4) how little will change without direct community involvement and oversight. KEYWORDS Marikana | South Africa | Department of Mineral Resources | South African Police Service | Lonmin • SUR 25 - v.14 n.25 • 61 - 69 | 2017 61 MASSACRE AT MARIKANA 1 • Introduction On 16 August 2012, 34 protesting mineworkers were shot and killed by members of the South African Police Service (SAPS) near a koppie1 in Marikana,2 located in South Africa’s North West Province. A further 79 mineworkers were injured and 259 were arrested. The mineworkers, employed to mine platinum at Lonmin’s Marikana operations,3 were protesting against Lonmin for a “living wage” of R12,500 per month (approx. $930). During the week preceding the shootings, 10 people were killed, including two private security guards and two police officers. The Commission of Inquiry (Marikana Commission) that was appointed by South African -

The Marikana Massacre and Lessons for the Left

The Marikana Massacre and Lessons for the Left Mary Smith TV coverage of the Marikana massacre dozen of the dead were cap- had a sickening sense of d´ej`avu about tured in news footage shot it; uniformed men, rifles aimed, the crack at the scene. The majority of gunfire, black bodies in the dust - of those who died, according Sharpeville, Soweto, iconic images of South to surviving strikers and re- Africa under Apartheid. But this was Au- searchers, were killed beyond gust 16th 2012, not the last century; the the view of cameras at a non- killers took their orders not from the old descript collection of boulders racist Apartheid regime of Botha or de some 300 metres behind Won- Klerk, but from the state headed by the derkop. `liberators' - the African National Congress (ANC). On one of these rocks, encom- Another image of South Africa: the passed closely on all sides by long patient queues, waiting since dawn solid granite boulders, is the to vote for the first time; hope and pride letter `N', the 14th letter of and joy in the faces. That was 1994 - the alphabet. Here, N repre- the year the struggle had smashed through sents the 14th body of a strik- Apartheid and ushered in a government led ing miner to be found by a po- by the ANC, pledged to `peace, jobs, free- lice forensics team in this iso- dom'. lated place. These letters are So how could it have come to this, used by forensics to detail were to state-sponsored murder, eighteen years the corpses lay. -

'Big Man', an Animated Film with an Accompanying Analysis of Its Relationship to the Theory and Practice of Art and Animation

'BIG MAN', AN ANIMATED FILM WITH AN ACCOMPANYING ANALYSIS OF ITS RELATIONSHIP TO THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF ART AND ANIMATION by Michelle Stewart Student Number: 875878231 Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Media and Cultural Studies University of KwaZulu-Natal, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa August 2016 DECLARATION I, Michelle Stewart, declare that The research reported in this thesis, except where otherwise indicated, is my original work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or examination at any other university. This thesis does not contain text, data, pictures, graphs or other information obtained from another person or source, unless specifically acknowledged as being so obtained. This thesis does not contain any other person’s writing, unless specifically acknowledged. Where such written sources have been used then they have always been acknowledged through the use of in-text quotation marks or indented paragraphs with accompanying in-text references and in the bibliography. This thesis does not contain text, graphics or tables copied and pasted from the Internet, unless specifically acknowledged through in-text references and in the bibliography. Student name: Michelle Stewart Signature: ________________________________ Date: ______________ As the supervisor, I acknowledge that this research dissertation/thesis is ready for examination. Name: Professor Anton Van der Hoven Signature: ________________________________ Date: _____________ As the co-supervisor, I acknowledge that this research dissertation/thesis is ready for examination. Name: Dr Louise Hall Signature: ________________________________ Date: _____________ ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Anton van der Hoven, for his consistent support and invaluable commentary. -

Intellectual Practices of a Poor People's Movement in Post

Interface: a journal for and about social movements Article Volume 6 (1): 185 – 210 (May 2014) Robertson, Professors of our own poverty Professors of our own poverty: intellectual practices of a poor people’s movement in post-apartheid South Africa Cerianne Robertson Abstract This paper addresses how a poor people’s movement contests dominant portrayals of ‘the poor’ as a violent mass in contemporary South African public discourse. To explore how Abahlali baseMjondolo, a leading poor people’s movement, articulates its own representation of ‘the poor,’ I examine two primary intellectual and pedagogical practices identified by movement members: first, discussion sessions in which members reflect on their experiences of mobilizing as Abahlali, and second, the website through which the movement archives a library of its own homegrown knowledge. I argue that these intellectual practices open new spaces for the poor to represent themselves to movement members and to publics beyond shack settlements. Through these spaces, Abahlali demonstrates and asserts the intelligence which exists in the shack settlements, and demands that its publics rethink dominant portrayals of ‘the poor.’ Keywords: Abahlali baseMjondolo, the poor, movement, intellectual and pedagogical practices, South Africa, post-apartheid Introduction On August 16, 2012, at a Lonmin platinum mine in Marikana, South Africa, 34 miners on strike were shot dead by police. South African and global press quickly dubbed the event, “The Marikana Massacre,” printing headlines such as “Killing Field”, “Mine Slaughter”, and “Bloodbath,” while videos of police shooting miners went viral and photographs showed bodies strewn on the ground (Herzkovitz, 2012). In September, South Africa’s Mail & Guardian reported that more striking miners “threw stones at officers” while “plumes of black smoke poured into the sky from burning tyres which workers used as barricades” ("Marikana," 2012). -

Marikana, Turning Point in South African History

Marikana, turning point in South African history By Peter Alexander∗ University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa Equating a ‘turning point’ with what William Sewell terms an ‘event’, it is argued that Marikana is a turning point in South African history. The massacre was a rupture that led to a sequence of further occurrences, notably a massive wave of strikes, which are changing structures that shape people’s lives. We have not yet reached the end of this chain of occurrences, and the scale of the turning point remains uncertain. In common with other events, Marikana has revealed structures unseen in normal times, providing an exceptional vantage point, allowing space for collective creativity, and enabling actors to envisage alternative futures. Keywords: South Africa; Marikana; Lonmin; massacre; turning point; event [Marikana, moment de´cisif de l’histoire sud-africaine.] Assimiler un « moment de´cisif » a` ce qu’appelle William Sewell un « e´ve`nement », il est avance´ que Marikana est un moment de´cisif de l’histoire sud-africaine. Le massacre est une rupture qui a mene´ a` une se´rie d’autres faits, notamment une vague importante de gre`ves, qui sont en train de changer les structures qui fac¸onnent la vie des populations. Nous n’avons pas encore atteint la fin de cette se´rie de faits, et l’e´chelle de ce moment de´cisif reste incertaine. Comme les autres e´ve`nements, Marikana a re´ve´le´ des structures jamais vues en temps normal, offrant un point de vue privile´gie´ exceptionnel, ainsi qu’un espace pour la cre´ativite´ collective, et permettant aux acteurs d’envisager un autre futur. -

Assessing How Far Democracy in South Africa Is Liberal Or Illiberal Written by Bryant Edward Harden

Assessing How Far Democracy in South Africa is Liberal or Illiberal Written by Bryant Edward Harden This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. Assessing How Far Democracy in South Africa is Liberal or Illiberal https://www.e-ir.info/2014/03/06/assessing-how-far-democracy-in-south-africa-is-liberal-or-illiberal/ BRYANT EDWARD HARDEN, MAR 6 2014 Introduction The history of South Africa includes a difficult path and a constant struggle of racism and inequality, of which remnants can be seen in present-day society. A territorial struggle involving trade posts, diamonds, gold, and societal expansion among different groups vying for control of what would become the Union of South Africa in 1910 eventually led to the establishment of the Republic of South Africa. This history involves complex relationships between “the Khoisan peoples, African pastoralists and farmers, ‘Boer’ European-descended settlers, and British imperialists” (Butler, 2003: 5). These economic and political struggles developed further in the mid-20th century as segregation laws were passed and the Afrikaner ‘Nationalist Party’ won power under the banner of ‘apartheid,’ meaning separation or apartness (ibid: 15). Under this slogan of apartheid, laws such as the Population Registration Act, Immorality Act, Group Areas Act, and Reservation of Separate Amenities Act further institutionalised the separation of White, Coloured, Indian, and African people (ibid: 17). In spite of these separatist laws, “the stagnation of the economy, the collapse of labour control, and urbanisation” led to collaboration between the African National Congress and the Nationalist Party (ibid: 23). -

South African Political Economy After Marikana

South African political economy after Marikana By Patrick Bond When a ruling party in any African country sinks to the depths of allowing its police force to serve white‐dominated multinational capital by killing dozens of black workers so as to end a brief strike, as happened in South Africa in August, it represents not just human‐rights and labour‐relations travesties. The incident offers the potential for a deep political rethink. But that can only happen if the society openly confronts the chilling lessons learned in the process about the moral degeneration of a liberation movement that the world had supported for decades. Support was near universal from progressives of all political hues, because that movement, the African National Congress (ANC), promised to rid this land not only of formal apartheid but of all unfair racial inequality and indeed class and gender exploitation as well. And now the ANC seems to be making many things worse. There are five immediate considerations about what happened at Marikana, 100km northwest of Johannesburg, beginning around 4pm on August 16: • South African police ordered several thousand striking platinum mineworkers – rock drill operators – off a hill where they had gathered as usual over the prior four days, surrounding the workers with barbed wire; • the hill was more than a kilometer away from Lonmin property, the mineworkers were not blocking mining operations or any other facility, and although they were on an ‘unprotected’ wildcat strike, the workers had a constitutional right to gather; -

South African Journalism and the Marikana Massacre: a Case Study of an Editorial Failure

The Political Economy of Communication 1(2), 65–88 © The Author 2013 http://www.polecom.org South African journalism and the Marikana massacre: A case study of an editorial failure Jane Duncan, Rhodes University Keywords: Marikana massacre; South African media; political economy; workers in the media; investigative journalism Abstract This article examines the early press coverage of the police massacre of striking mineworkers in Marikana, South Africa, on the 16th of August 2012. It includes a quantitative and qualitative content analysis of a representative coverage sample from the country’s mainstream newspapers. From this analysis, it is apparent that the coverage was heavily biased towards official accounts of the massacre, and that it overwhelmingly favoured business sources of news and analysis. Business sources were the most likely to be primary definers of news stories. In contrast, the miners’ voices barely featured independently of the main trade union protagonists, which was significant as many miners did not feel sufficiently represented by the unions. The failure of journalists to speak to miners sufficiently led to a major editorial failure in the early press coverage, as it failed to reveal the full extent of police violence against the miners. As a result, the police version of events was allowed to stand largely unchallenged before a group of academics put the fuller account into the public domain after having interviewed miners. The coverage also contained dominant themes which portrayed the miners as inherently violent, disposed to irrationality and even criminality. The article traces the problems that arose in the coverage, specifically, in regard to organisational and occupational demands in South African newsrooms.