Puyer-Yayer: Myths and Rituals of Ancestor Spirits with Buddhism in Luang Prabang, Lao PDR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

غhistorical Presentations in the Lao Textbooks

Historical Presentations in the Lao Textbooks: From the Independent to the Early Socialism Period (1949-1986)1 Dararat Mattariganond Û Yaowalak Apichatvullop This paper presents the presentations of Lao history in the Lao textbooks from the Independent period, starting in 1949 to the Early Socialism period, starting in 1975. We designate the year 1949 as the starting point of our study as it was this year that the Royal Lao Government (RLG) proclaimed independence from France on 19 July. It was also this year that Lao gained international recognition as an independent state, although it was still within the French Union. At the other end, we take the year 1986, as it was the year that the Lao Government declared the new policy çJintanakarn Mai,é which involved a number of changes in Lao 1 Paper presented in First International Conference on Lao Studies, organized by Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL, May 20-22, 2005. 88 «“√ “√ —ߧ¡≈ÿà¡πÈ”‚¢ß social structures. Our purpose is to show that history was manipulated by the Lao governments of both periods as a mechanism to transfer the national social values to the younger generations through textbooks used in school education. Our analysis is based on the Lao textbooks used during the Independent and the Socialism periods (1949- 1986). Presentations of this paper are in two parts: 1) the Lao history in the Lao textbooks of the Independent period (1949-1975), and 2) the Lao history in the Lao textbooks of the Early Socialism period (1975-1986). 1. Lao History Before 1975 Based on Lao historical documents, the Lan Xang kingdom used to be a well united state during King Fa Ngumûs regime. -

Cultural Landscape and Indigenous Knowledge of Natural Resource and Environment Management of Phutai Tribe

CULTURAL LANDSCAPE AND INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE OF NATURAL RESOURCE AND ENVIRONMENT MANAGEMENT OF PHUTAI TRIBE By Mr. Isara In-ya A Thesis Submitted in Partial of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Architectural Heritage Management and Tourism International Program Graduate School, Silpakorn University Academic Year 2014 Copyright of Graduate School, Silpakorn University CULTURAL LANDSCAPE AND INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE OF NATURAL RESOURCE AND ENVIRONMENT MANAGEMENT OF PHUTAI TRIBE By Mr. Isara In-ya A Thesis Submitted in Partial of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Architectural Heritage Management and Tourism International Program Graduate School, Silpakorn University Academic Year 2014 Copyright of Graduate School, Silpakorn University The Graduate School, Silpakorn University has approved and accredited the Thesis title of “Cultural landscape and Indigenous Knowledge of Natural Resource and Environment Management of Phutai Tribe” submitted by Mr.Isara In-ya as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architectural Heritage Management and Tourism. …………………………………………………………... (Associate Professor Panjai Tantatsanawong, Ph.D.) Dean of Graduate School ……..……./………..…./…..………. The Thesis Advisor Professor Ken Taylor The Thesis Examination Committee …………………………………………Chairman (Associate Professor Chaiyasit Dankittikul, Ph.D.) …………../...................../................. …………………………………………Member (Emeritus Professor Ornsiri Panin) …………../...................../................ -

Case of Luang Prabang, Lao PDR

sustainability Article Impact of Tourism Growth on the Changing Landscape of a World Heritage Site: Case of Luang Prabang, Lao PDR Ceelia Leong 1,*, Jun-ichi Takada 2, Shinya Hanaoka 2 and Shinobu Yamaguchi 3 1 Department of International Development Engineering, Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Tokyo 152-8550, Japan 2 Department of Transdisciplinary Science and Engineering, School of Environment and Society, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Tokyo 152-8550, Japan; [email protected] (J.-i.T.); [email protected] (S.H.) 3 Global Scientific and Computing Center, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Tokyo 152-8550, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-3-5734-3282 Received: 2 October 2017; Accepted: 27 October 2017; Published: 1 November 2017 Abstract: Rapid tourism development adversely impacts and negatively transforms World Heritage Sites. This study aimed at examining how tourism growth has impacted the built environment of Luang Prabang, Lao PDR through an empirical approach. Luang Prabang has received a critical warning from World Heritage Committee for the escalating development pressure on its vulnerable landscape. Hence, this study examined two aspects: (1) the spatial pattern of the increase of touristic usage; and (2) the relation between the increase of touristic usage and the significant changes in the built environment. For this, geographical information systems (GIS) are combined with statistical methods such as logistic regression and chi-square test of independence. The results affirmed that the change from other types of usage to touristic usage in existing buildings has a higher chance to occur along riverbank areas than in the middle of the peninsula in the core heritage area. -

Highlights of Laos Go Beyond Tour │Physical Level 2 Bangkok - Luang Prabang - Phonsavan - Vang Vieng - Vientiane - Khong Island - Pakse

Highlights of Laos Go Beyond Tour │Physical Level 2 Bangkok - Luang Prabang - Phonsavan - Vang Vieng - Vientiane - Khong Island - Pakse An introduction to the pristine beauty of Laos, this 2-week journey ticks off all of the top sights, such as Luang Prabang, Plain of Jars and 4,000 Islands, as well as visiting little-explored villages to meet the friendly, local communities. • Get spiritual in Luang Prabang • Observe the monks for Takbat • Admire the mystical Kuangsi waterfalls • Wonder at the Plain of Jars • Discover scenic Vang Vieng • Stroll through quaint Vientiane • Unwind at the 4000 islands Visit wendywutours.co.nz Call 0800 936 3998 to speak to a Reservations Consultant Highlights of Laos tour inclusions: ▪ Return international economy flights, taxes and current fuel surcharges (unless a land only option is selected) ▪ All accommodation ▪ Meals as stated on your itinerary ▪ All sightseeing and entrance fees ▪ All transportation and transfers ▪ English speaking National Escort (if your group is 10 or more passengers) or Local Guides ▪ Visa fees for New Zealand passport holders ▪ Specialist advice from our experienced travel consultants ▪ Comprehensive travel guides The only thing you may have to pay for are personal expenditure e.g. drinks, optional excursions or shows, insurance of any kind, tipping, early check in or late checkout and other items not specified on the itinerary. Go Beyond Tours: Venture off the beaten track to explore fascinating destinations away from the tourist trail. You will discover the local culture in depth and see sights rarely witnessed by other travellers. These tours take you away from the comforts of home but will reward you with the experiences of a lifetime. -

Dress and Identity Among the Black Tai of Loei Province, Thailand

DRESS AND IDENTITY AMONG THE BLACK TAI OF LOEI PROVINCE, THAILAND Franco Amantea Bachelor of Arts, Simon Fraser University 2003 THESIS SUBMITTED 1N PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Sociology and Anthropology O Franco Amantea 2007 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY 2007 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Franco Amantea Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: Dress and Identity Among the Black Tai of Loei Province, Thailand Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Gerardo Otero Professor of Sociology Dr. Michael Howard Senior Supervisor Professor of Anthropology Dr. Marilyn Gates Supervisor Associate Professor of Anthropology Dr. Brian Hayden External Examiner Professor of Archaeology Date Defended: July 25,2007 Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the "Institutional Repository" link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/handle/1892/112>) and, without changing the content, to translate the thesis/project or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

The Loss of the Ou River by Saimok

The Loss of the Ou River By Saimok “Talaeng taeng talam bam!” Sounds of warning: “I am coming to get you!” Khmu children play hide and seek along the banks of the Ou River in North- ern Laos. Ngoi district, Luangprabang province. November 2019. photo by author The Loss of 2 the Ou River The first time I saw the Ou River I was mesmer- Arriving in the northern province of Phongsa- ized by its beauty: the high karst mountains, the ly province by truck, I was surprised that this dense jungle, the structure of the river and the remote corner of the land of a million elephants flow of its waters. The majority of the people felt like a new province of China. Chinese lux- along the Ou River are Khmu, like me. We under- ury cars sped along the bumpy road, posing a stand one another. Our Khmu people belong to danger to the children playing along the dusty specific clans, and my Sim Oam family name en- roadside. In nearly every village I passed, the sures the protection and care of each Sim Oam newer concrete homes featured tiles bearing clan member I meet along my journey. Mao Zedong’s image. “I’ve seen this image in many homes in this area. May I ask who he is?” I Sim Oam is similar to a kingfisher, and as mem- asked the village leader at a local truck stop. bers of the Sim Oam clan, we must protect this animal, and not hunt it. If a member of our clan breaks the taboo and hunts a sim oam, his teeth will fall out and his eyesight will become cloudy. -

Study of the Provincial Context in Oudomxay 1

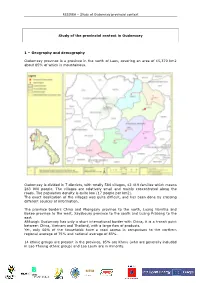

RESIREA – Study of Oudomxay provincial context Study of the provincial context in Oudomxay 1 – Geography and demography Oudomxay province is a province in the north of Laos, covering an area of 15,370 km2 about 85% of which is mountainous. Oudomxay is divided in 7 districts, with totally 584 villages, 42 419 families which means 263 000 people. The villages are relatively small and mainly concentrated along the roads. The population density is quite low (17 people per km2). The exact localization of the villages was quite difficult, and has been done by crossing different sources of information. The province borders China and Phongsaly province to the north, Luang Namtha and Bokeo province to the west, Xayaboury province to the south and Luang Prabang to the east. Although Oudomxay has only a short international border with China, it is a transit point between China, Vietnam and Thailand, with a large flow of products. Yet, only 66% of the households have a road access in comparison to the northern regional average of 75% and national average of 83%. 14 ethnic groups are present in the province, 85% are Khmu (who are generally included in Lao Theung ethnic group) and Lao Loum are in minority. MEM Lao PDR RESIREA – Study of Oudomxay provincial context 2- Agriculture and local development The main agricultural crop practiced in Oudomxay provinces is corn, especially located in Houn district. Oudomxay is the second province in terms of corn production: 84 900 tons in 2006, for an area of 20 935 ha. These figures have increased a lot within the last few years. -

Public Green Spaces and Parks for Tourists and Citizens in Luang Prabang, Laos

Welcome to Luang Prabang World Heritage Town Public Green Spaces and Parks for Tourists and Citizens in Luang Prabang, Laos Prepared by: Urban Development and Administration Authority (UDAA), Luang Prabang, Laos 1 Luang Prabang World Heritage Site Mekong River Namkhan River 2 The Existing of Public Green Spaces and Parks for Tourists and Citizens Prepared by: Urban Development and Administration Authority (UDAA), Luang Prabang, Laos 3 Master Plan of Heritage Preservation and Development (PSMV), 2001 Green areas along mountains Phousi Mount Green areas along wetlands Green areas along river banks 4 Master Plan of Buffer Zone, 2012 Green areas of mountains around city Green areas of agricultural fields 5 Design and Maintenance and Challenges faced regarding Public Green Spaces and Parks for Tourists and Citizens Prepared by: Urban Development and Administration Authority (UDAA), Luang Prabang, Laos 6 Green Spaces in the City Luang Prabang World Heritage Site Protection and Preservation Zones Road-junctions & Parks Small Public Park . Green area along mountains Small Public Park . Green area along rivers . Green area along wetlands Temples & Trees 7 ASEAN ESC Model Cities Programme Activities Wastewater • Master plan for Urban Drainage and Sewerage System in Luang Prabang Municipality Year 2012-2037, funded by French Agency for Development (AFD). • Decentralized Wastewater Treatment Solutions Completed and (DEWATS), 2014/15, funded by Institute for Global implementing Environmental Strategies (IGES). DEWATS Solid waste • LPPE project for : On-site composting activity, Eco- Basket activity, and 3Rs activity. Funded by Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). Completed and operating 8 Problems and Challenges faced Finance • Limitation of finance for construction/improvement work • Lack of cost for operation /maintenance work • Lack of sustainability of the invested protects Wetlands • Maintenance (protection) of wetlands/ponds is the most challenge faced in maintain green spaces. -

Laos and Ethnic Minority Cultures: Promoting Heritage Edited by Yves Goudineau

Laos and Ethnic Minority Cultures: Promoting Heritage Edited by Yves Goudineau UNESCO PUBLISHING MEMORY OF PEOPLES 34_Laos_GB_INT 26/06/03 10:24 Page 1 Laos and Ethnic Minority Cultures 34_Laos_GB_INT 26/06/03 10:24 Page 3 Laos and Ethnic Minority Cultures: Promoting Heritage Edited by YVES GOUDINEAU Memory of Peoples | UNESCO Publishing 34_Laos_GB_INT 7/07/03 11:12 Page 4 The authors are responsible for the choice and the presentation of the facts contained in this book and for the opinions expressed therein, which are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. UNESCO wishes to express its gratitude to the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs for its support to this publication through the UNESCO/Japan Funds-in-Trust for the Safeguarding and Promotion of Intangible Heritage. Published in 2003 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, place de Fontenoy F-75352 Paris 07 SP Plate section: Marion Dejean Cartography and drawings: Marina Taurus Composed by La Mise en page Printed by Imprimerie Leclerc, Abbeville, France ISBN 92-3-103891-5 © UNESCO 2003 Printed in France 34_Laos_GB_INT 26/06/03 10:24 Page 5 5 Foreword YVES GOUDINEAU It is quite clear to every observer that Laos owes part of its cultural wealth to the unique diversity which resides in the bosom of the different populations that have settled on its present territory down the ages, bringing with them a mix of languages, beliefs and aesthetic traditions. -

Destinations Luang Say Mekong Cruise 3 Days

BestPrice Travel., JSC Address: 12A, Ba Trieu Alley, Ba Trieu Street, Hai Ba Trung District, Hanoi, Vietnam Email: [email protected] Tel: +84 436-249-007 Fax: +84 436-249-007 Website: https://bestpricevn.com Tour Luang Say Mekong Cruise 3 days Itinerary Itinerary Overview Includes & Excludes Detail Itinerary I. Itinerary Overview Date Activities Accommodations Meals DOWN RIVER : Houei Sai -> Luang Prabang Day 1 HUAY XAI > VILLAGE > PAKBENG Luang Say Lodge L, D Day 2 PAKBENG > BAW VILLAGE > KAMU LODGE Kamu Lodge Lodge B, L, D Day 3 KAMU LODGE > PAK OU > LUANG PRABANG B, L UP RIVER: Luang Prabang -> Houei Sai Day 3 LUANG PRABANG > PAK OU > KAMU LODGE Kamu Lodge L, D Day 2 KAMU LODGE > BAW VILLAGE > LUANG SAY LODGE B, L, D Day 3 PAKBENG > VILLAGE > HUAY XAI B, L II. Includes & Excludes Includes -Transfer from Laos’s immigration to the pier in Houayxay or v.v. - 2 days cruise with stops and visits en route - 1 night accommodation at the Luang Say Lodge - Meal plan as mentioned in the program - ( 2 lunches, 1 dinner, 2 breakfasts ) - Coffee, tea & drinking water on board and during meals. - Admission fee at visiting points as mentioned in the program. - Services of qualified crews during the cruise Excludes - Transfer from/to hotel to pier in Luang Prabang - Shuttle boats to Chiang Khong / Houayxayor Houayxay / Chiang Khong - Immigration fees in Houayxay - Soft and Alcoholic Drinks during the trip. - visa approval and fees for Laos - Services in Luang Prabang - Personal insurance - Other personal expenses III. Detail Itinerary DOWN RIVER : Houei Sai -> Luang Prabang Day 1 HUAY XAI > VILLAGE > PAKBENG The Luang Say riverboat leaves Houai Xay pier at 09h30am(please be at Luang Say Houei Sai office not later than at 8.30am) for cruising down the Mekong River to Luang Say Lodge in Pakbeng. -

Tourist Map 8 Northern Provinces of Laos Ph

czomujmjv'mjP; ) c0;'rkdg|nv0v']k; Xiangseo Menkouapoung Sudayngam Tourist Map 8 Northern Provinces of Laos Ph. Kotosan Bosao Ou Nua Pacha Ph. Kheukaysan Nam Khang Ou Tai Nam OU Yofam Phou Den Din Ngay nua Nam Ngay NPA 1A Hat Sa Noy Nam Khong PHONGSALI Nam Houn Boun Neua Ya Poung Bo may Chi Cho Nam Boun Nam Leng Ban Yo Pakha 1B Boun Tai PHONGSALI Nam Ban Nam Li Xieng Mom Sanomay Samphanh Kheng Aya Mohan Chulaosen Nam Ou Sop Houn Tay Trang Muang Sing Namly Muang May Boten Lak Kham Ma Meochai Picheumua Khouang Bouamphanh Sophoun LUANG Tin Nam Tha Khoa Omtot That NAMTHA Donexay Na Teuy Kok Phao Sin Xai Pang Tong Khoung Muang Khua Kok Hine Nam Phak 2E Thad Sop Kai Fate Nam Yang Nam Pheng Gnome Pakha Kang Kao Long LUANGNAMTHA Pang Thong Xieng Kok Na Tong Houay Pae Somepanema Na Mor Nam Ou Chaloen Suk Hattat Keo Choub Hat Aine Nam Ha Huoi Puoc Nam Fa Phou Thong Muang La Pha Dam Nam Ha Nam Bak Na Son Xieng Dao Samsop Kou Long Muang Et Nam Sing Nam Le Houay La Xiang Kho Pha Ngam Nam Ma Tha Luang Nam Eng Houay Gnung Houay Sou Muang Meung Phou Lanh Hatnaleng Muang Ngoi Muang Per Sop Bao Nong Kham Nam Kon Pahang Huai NamKha Sang At OUDOM XAI Bom Ph. Phakhao Tang Or Vieng Phoukha LUANG PRABANG Ph. Houaynamkat Nam Et Houay Lin HOUA PHAN Nam Ngeun Guy Prabat Nam You Pang Xai Hat Lom Song Cha Nam Bak Nong Khiew Namti Namon Pak Mong Pha Tok Muang Kao Sop Hao Nam Phae Lai Lot Nam Chi Lak 32 OUDOM XAI Nam Khan Bouamban Hang Luang Sin Jai Nale Houay Houm Phu Ban Sang BOKEO Phiahouana Nam Thouam Long Xot Siengda Sam Ton LUANG Vieng Kham Muang Xon Ban Mom -

Conflict in Laos: the Politics of Neutralization Joel Halpern University of Massachusetts, Amherst, [email protected]

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Anthropology Department Faculty Publication Anthropology Series August 1965 Conflict in Laos: the Politics of Neutralization Joel Halpern University of Massachusetts, Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/anthro_faculty_pubs Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Halpern, Joel, "Conflict in Laos: the Politics of Neutralization" (1965). The Journal of Asian Studies. 18. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/anthro_faculty_pubs/18 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Department Faculty Publication Series by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Conflict in Laos: the Politics of Neutralization. Review Author[s] : Joel M. Halpern The Journal ofAsian Studies, Vol. 24, No. 4 (Aug., 1965), 703-704. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0021-9118%28196508%2924%3A4%3C703%3ACILTP0%3E2.O.CO%3B2-O The Journal of Asian Studies is currently published by Association for Asian Studies. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work.