Case of Luang Prabang, Lao PDR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LAOS Opium Survey 2003

LAOS Opium Survey 2003 June 2003 Laos Opium Survey 2003 Abbreviations GOL Government of Lao PDR ICMP UNODC Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme LCDC Lao National Commission for Drug Control and Supervision NSC Lao National Statistics Centre PFU Programme Facilitation Unit UNODC United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Acknowledgements The following organisation and individuals contributed to the implementation of the 2003 opium survey in Lao PDR (Laos) and the preparation of the present report: Government of Lao PDR: Lao National Commission for Drug Control and Supervision National Statistics Centre National Geographic Department Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry The implementation of the survey would not have been possible without the support from the local administrations and the dedicated work of the field surveyors. UNODC: Shariq Bin Raza, Officer-in-charge, UNODC (Field Office - Laos) Leik Boonwaat, Programme Facilitation Unit UNODC (Field Office - Laos) Hakan Demirbuken, Survey data and systems Analyst (ICMP- Research Section) Denis Destrebecq, Survey technical supervision (ICMP-Research Section) Giovanni Narciso, Regional Illicit Crop Monitoring Expert (ICMP-Field Office Myanmar) Thibault le Pichon, Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme Manager (ICMP- Research Section) The implementation of UNODC’s Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme in Southeast Asia and the 2003 Laos Opium survey were made possible thanks to financial support from the Governments of the USA, Japan and Italy. NOTE: This publication has not been formally edited. Laos Opium Survey 2003 LAOS OPIUM SURVEY 2003 Executive Summary Although far behind Afghanistan and Myanmar, the remote and mountainous areas of Northern Laos, which border Thailand, Myanmar, China and Vietnam, have consistently come in third place as a source of the world’s illicit opium and heroin during the last ten years. -

An Assessment of Wildlife Use by Northern Laos Nationals

animals Article An Assessment of Wildlife Use by Northern Laos Nationals Elizabeth Oneita Davis * and Jenny Anne Glikman San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research, 15600 San Pasqual Valley Rd, Escondido, CA 92026, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 17 March 2020; Accepted: 8 April 2020; Published: 15 April 2020 Simple Summary: Although unsustainable wildlife consumption is a leading threat to biodiversity in Southeast Asia, there is still a notable lack of research around the issue, particularly into which animals may be “on the horizon” of impending conservation concern. Using semistructured interviews, we investigated the consumption of wildlife in northern Laos, with a focus on the use of wildlife for medicinal purposes. Bear bile was the most popular product, but serow bile was second in popularity and used for similar ailments. In light of these results, and considering the vulnerability of both bear and serow populations in the wild, greater concern needs to be taken to reduce demand for these products, before this demand becomes a significant conservation challenge. Abstract: Unsustainable wildlife trade is a well-publicized area of international concern in Laos. Historically rich in both ethnic and biological diversity, Laos has emerged in recent years as a nexus for cross-border trade in floral and faunal wildlife, including endangered and threatened species. However, there has been little sustained research into the scale and scope of consumption of wildlife by Laos nationals themselves. Here, we conducted 100 semistructured interviews to gain a snapshot of consumption of wildlife in northern Laos, where international and in some cases illegal wildlife trade is known to occur. -

Highlights of Laos Go Beyond Tour │Physical Level 2 Bangkok - Luang Prabang - Phonsavan - Vang Vieng - Vientiane - Khong Island - Pakse

Highlights of Laos Go Beyond Tour │Physical Level 2 Bangkok - Luang Prabang - Phonsavan - Vang Vieng - Vientiane - Khong Island - Pakse An introduction to the pristine beauty of Laos, this 2-week journey ticks off all of the top sights, such as Luang Prabang, Plain of Jars and 4,000 Islands, as well as visiting little-explored villages to meet the friendly, local communities. • Get spiritual in Luang Prabang • Observe the monks for Takbat • Admire the mystical Kuangsi waterfalls • Wonder at the Plain of Jars • Discover scenic Vang Vieng • Stroll through quaint Vientiane • Unwind at the 4000 islands Visit wendywutours.co.nz Call 0800 936 3998 to speak to a Reservations Consultant Highlights of Laos tour inclusions: ▪ Return international economy flights, taxes and current fuel surcharges (unless a land only option is selected) ▪ All accommodation ▪ Meals as stated on your itinerary ▪ All sightseeing and entrance fees ▪ All transportation and transfers ▪ English speaking National Escort (if your group is 10 or more passengers) or Local Guides ▪ Visa fees for New Zealand passport holders ▪ Specialist advice from our experienced travel consultants ▪ Comprehensive travel guides The only thing you may have to pay for are personal expenditure e.g. drinks, optional excursions or shows, insurance of any kind, tipping, early check in or late checkout and other items not specified on the itinerary. Go Beyond Tours: Venture off the beaten track to explore fascinating destinations away from the tourist trail. You will discover the local culture in depth and see sights rarely witnessed by other travellers. These tours take you away from the comforts of home but will reward you with the experiences of a lifetime. -

The Loss of the Ou River by Saimok

The Loss of the Ou River By Saimok “Talaeng taeng talam bam!” Sounds of warning: “I am coming to get you!” Khmu children play hide and seek along the banks of the Ou River in North- ern Laos. Ngoi district, Luangprabang province. November 2019. photo by author The Loss of 2 the Ou River The first time I saw the Ou River I was mesmer- Arriving in the northern province of Phongsa- ized by its beauty: the high karst mountains, the ly province by truck, I was surprised that this dense jungle, the structure of the river and the remote corner of the land of a million elephants flow of its waters. The majority of the people felt like a new province of China. Chinese lux- along the Ou River are Khmu, like me. We under- ury cars sped along the bumpy road, posing a stand one another. Our Khmu people belong to danger to the children playing along the dusty specific clans, and my Sim Oam family name en- roadside. In nearly every village I passed, the sures the protection and care of each Sim Oam newer concrete homes featured tiles bearing clan member I meet along my journey. Mao Zedong’s image. “I’ve seen this image in many homes in this area. May I ask who he is?” I Sim Oam is similar to a kingfisher, and as mem- asked the village leader at a local truck stop. bers of the Sim Oam clan, we must protect this animal, and not hunt it. If a member of our clan breaks the taboo and hunts a sim oam, his teeth will fall out and his eyesight will become cloudy. -

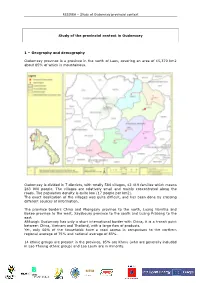

Study of the Provincial Context in Oudomxay 1

RESIREA – Study of Oudomxay provincial context Study of the provincial context in Oudomxay 1 – Geography and demography Oudomxay province is a province in the north of Laos, covering an area of 15,370 km2 about 85% of which is mountainous. Oudomxay is divided in 7 districts, with totally 584 villages, 42 419 families which means 263 000 people. The villages are relatively small and mainly concentrated along the roads. The population density is quite low (17 people per km2). The exact localization of the villages was quite difficult, and has been done by crossing different sources of information. The province borders China and Phongsaly province to the north, Luang Namtha and Bokeo province to the west, Xayaboury province to the south and Luang Prabang to the east. Although Oudomxay has only a short international border with China, it is a transit point between China, Vietnam and Thailand, with a large flow of products. Yet, only 66% of the households have a road access in comparison to the northern regional average of 75% and national average of 83%. 14 ethnic groups are present in the province, 85% are Khmu (who are generally included in Lao Theung ethnic group) and Lao Loum are in minority. MEM Lao PDR RESIREA – Study of Oudomxay provincial context 2- Agriculture and local development The main agricultural crop practiced in Oudomxay provinces is corn, especially located in Houn district. Oudomxay is the second province in terms of corn production: 84 900 tons in 2006, for an area of 20 935 ha. These figures have increased a lot within the last few years. -

Acts of the Ten Years of Decentralised Cooperation Chinon

TEN YEARS OF DECENTRALISED COOPERATION BETWEEN THE CITIES OF CHINON AND LUANG PRABANG SPONSORED BY UNESCO TEN YEARS OF DECENTRALISED COOPERATION BETWEEN THE CITIES OF CHINON AND LUANG PRABANG SPONSORED BY UNESCO TEN YEARS OF DECENTRALISED COOPERATION BETWEEN THE CITIES OF CHINON AND LUANG PRABANG SPONSORED BY UNESCO This publication is a collective work produced by the Chinon Development and City Planning Agency, under the coordination of Ms. Cathy Savourey, assisted by Ms. Aude Sivigny. This publication was conceived on the initiative of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which has from the beginning responded energetically to the request of UNESCO and the Laotian government for the establishment of a decentralised cooperation programme for the World Heritage City of Luang Prabang. Its preparation and publication were made possible through funding from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the French Development Agency, the Centre region of France (Région Centre) and the France-UNESCO Cooperation Agreement for Heritage. The editorial team expresses its thanks to Ms. Minja Yang, Mr. Yves Dauge and Ms. Emmanuelle Robert for their guidance in the preparation of this publication. cover Meeting of the Nam Khan and Mekong rivers in Luang Prabang during the dry season, aerial photo taken by kite © Nicolas Chorier, May 2004 photo credits Karine Amarine, Michel Brodovitch, Philippe Colucci, Felipe Delmont, Francis Engelmann, Pierre Guédant, Cathy Savourey, Aude Sivigny, Anne-Gaëlle Verdier, and all particiapants who provided documentation and archival material layout Laurent Bruel et Nicolas Frühauf The Chinon–Luang Prabang decentralised cooperation programme was awarded the Grand Prize for Cooperation from the High Commissioner for International Cooperation in 2001. -

Public Green Spaces and Parks for Tourists and Citizens in Luang Prabang, Laos

Welcome to Luang Prabang World Heritage Town Public Green Spaces and Parks for Tourists and Citizens in Luang Prabang, Laos Prepared by: Urban Development and Administration Authority (UDAA), Luang Prabang, Laos 1 Luang Prabang World Heritage Site Mekong River Namkhan River 2 The Existing of Public Green Spaces and Parks for Tourists and Citizens Prepared by: Urban Development and Administration Authority (UDAA), Luang Prabang, Laos 3 Master Plan of Heritage Preservation and Development (PSMV), 2001 Green areas along mountains Phousi Mount Green areas along wetlands Green areas along river banks 4 Master Plan of Buffer Zone, 2012 Green areas of mountains around city Green areas of agricultural fields 5 Design and Maintenance and Challenges faced regarding Public Green Spaces and Parks for Tourists and Citizens Prepared by: Urban Development and Administration Authority (UDAA), Luang Prabang, Laos 6 Green Spaces in the City Luang Prabang World Heritage Site Protection and Preservation Zones Road-junctions & Parks Small Public Park . Green area along mountains Small Public Park . Green area along rivers . Green area along wetlands Temples & Trees 7 ASEAN ESC Model Cities Programme Activities Wastewater • Master plan for Urban Drainage and Sewerage System in Luang Prabang Municipality Year 2012-2037, funded by French Agency for Development (AFD). • Decentralized Wastewater Treatment Solutions Completed and (DEWATS), 2014/15, funded by Institute for Global implementing Environmental Strategies (IGES). DEWATS Solid waste • LPPE project for : On-site composting activity, Eco- Basket activity, and 3Rs activity. Funded by Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). Completed and operating 8 Problems and Challenges faced Finance • Limitation of finance for construction/improvement work • Lack of cost for operation /maintenance work • Lack of sustainability of the invested protects Wetlands • Maintenance (protection) of wetlands/ponds is the most challenge faced in maintain green spaces. -

Destinations Luang Say Mekong Cruise 3 Days

BestPrice Travel., JSC Address: 12A, Ba Trieu Alley, Ba Trieu Street, Hai Ba Trung District, Hanoi, Vietnam Email: [email protected] Tel: +84 436-249-007 Fax: +84 436-249-007 Website: https://bestpricevn.com Tour Luang Say Mekong Cruise 3 days Itinerary Itinerary Overview Includes & Excludes Detail Itinerary I. Itinerary Overview Date Activities Accommodations Meals DOWN RIVER : Houei Sai -> Luang Prabang Day 1 HUAY XAI > VILLAGE > PAKBENG Luang Say Lodge L, D Day 2 PAKBENG > BAW VILLAGE > KAMU LODGE Kamu Lodge Lodge B, L, D Day 3 KAMU LODGE > PAK OU > LUANG PRABANG B, L UP RIVER: Luang Prabang -> Houei Sai Day 3 LUANG PRABANG > PAK OU > KAMU LODGE Kamu Lodge L, D Day 2 KAMU LODGE > BAW VILLAGE > LUANG SAY LODGE B, L, D Day 3 PAKBENG > VILLAGE > HUAY XAI B, L II. Includes & Excludes Includes -Transfer from Laos’s immigration to the pier in Houayxay or v.v. - 2 days cruise with stops and visits en route - 1 night accommodation at the Luang Say Lodge - Meal plan as mentioned in the program - ( 2 lunches, 1 dinner, 2 breakfasts ) - Coffee, tea & drinking water on board and during meals. - Admission fee at visiting points as mentioned in the program. - Services of qualified crews during the cruise Excludes - Transfer from/to hotel to pier in Luang Prabang - Shuttle boats to Chiang Khong / Houayxayor Houayxay / Chiang Khong - Immigration fees in Houayxay - Soft and Alcoholic Drinks during the trip. - visa approval and fees for Laos - Services in Luang Prabang - Personal insurance - Other personal expenses III. Detail Itinerary DOWN RIVER : Houei Sai -> Luang Prabang Day 1 HUAY XAI > VILLAGE > PAKBENG The Luang Say riverboat leaves Houai Xay pier at 09h30am(please be at Luang Say Houei Sai office not later than at 8.30am) for cruising down the Mekong River to Luang Say Lodge in Pakbeng. -

Tourist Map 8 Northern Provinces of Laos Ph

czomujmjv'mjP; ) c0;'rkdg|nv0v']k; Xiangseo Menkouapoung Sudayngam Tourist Map 8 Northern Provinces of Laos Ph. Kotosan Bosao Ou Nua Pacha Ph. Kheukaysan Nam Khang Ou Tai Nam OU Yofam Phou Den Din Ngay nua Nam Ngay NPA 1A Hat Sa Noy Nam Khong PHONGSALI Nam Houn Boun Neua Ya Poung Bo may Chi Cho Nam Boun Nam Leng Ban Yo Pakha 1B Boun Tai PHONGSALI Nam Ban Nam Li Xieng Mom Sanomay Samphanh Kheng Aya Mohan Chulaosen Nam Ou Sop Houn Tay Trang Muang Sing Namly Muang May Boten Lak Kham Ma Meochai Picheumua Khouang Bouamphanh Sophoun LUANG Tin Nam Tha Khoa Omtot That NAMTHA Donexay Na Teuy Kok Phao Sin Xai Pang Tong Khoung Muang Khua Kok Hine Nam Phak 2E Thad Sop Kai Fate Nam Yang Nam Pheng Gnome Pakha Kang Kao Long LUANGNAMTHA Pang Thong Xieng Kok Na Tong Houay Pae Somepanema Na Mor Nam Ou Chaloen Suk Hattat Keo Choub Hat Aine Nam Ha Huoi Puoc Nam Fa Phou Thong Muang La Pha Dam Nam Ha Nam Bak Na Son Xieng Dao Samsop Kou Long Muang Et Nam Sing Nam Le Houay La Xiang Kho Pha Ngam Nam Ma Tha Luang Nam Eng Houay Gnung Houay Sou Muang Meung Phou Lanh Hatnaleng Muang Ngoi Muang Per Sop Bao Nong Kham Nam Kon Pahang Huai NamKha Sang At OUDOM XAI Bom Ph. Phakhao Tang Or Vieng Phoukha LUANG PRABANG Ph. Houaynamkat Nam Et Houay Lin HOUA PHAN Nam Ngeun Guy Prabat Nam You Pang Xai Hat Lom Song Cha Nam Bak Nong Khiew Namti Namon Pak Mong Pha Tok Muang Kao Sop Hao Nam Phae Lai Lot Nam Chi Lak 32 OUDOM XAI Nam Khan Bouamban Hang Luang Sin Jai Nale Houay Houm Phu Ban Sang BOKEO Phiahouana Nam Thouam Long Xot Siengda Sam Ton LUANG Vieng Kham Muang Xon Ban Mom -

Do Relocated Villages Experience More Forest Cover Change? Resettlements, Shifting Cultivation and Forests in the Lao PDR

Environments 2015, 2, 250–279; doi:10.3390/environments2020250 OPEN ACCESS environments ISSN 2076-3298 www.mdpi.com/journal/environments Article Do Relocated Villages Experience More Forest Cover Change? Resettlements, Shifting Cultivation and Forests in the Lao PDR Sébastien Boillat 1,2,*, Corinna Stich 1, Joan Bastide 1,3, Michael Epprecht 3, Sithong Thongmanivong 4 and Andreas Heinimann 3 1 Department of Geography and Environment, University of Geneva, Uni Mail, 40 Bd du Pont-d’Arve, CH-1211 Genève 4, Switzerland; E-Mails: [email protected] (C.S.); [email protected] (J.B.) 2 Centro de Ciência do Sistema Terrestre, National Institute for Space Research (INPE), Av. dos Astronautas, 1758, CEP 12201-027, São José dos Campos 12630-000, Brazil 3 Centre for Development and Environment & Institute of Geography, University of Bern, Hallerstrasse 10, Bern CH-3012, Switzerland; E-Mails: [email protected] (M.E.); [email protected] (A.H.) 4 Faculty of Forestry, National University of Laos, Dongdok, Xaythany District, Vientiane 7332, Laos; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +41-22-379-83-32; Fax: +41-22-379-83-53. Academic Editor: Yu-Pin Lin Received: 30 December 2014 / Accepted: 5 June 2015 / Published: 12 June 2015 Abstract: This study explores the relationships between forest cover change and the village resettlement and land planning policies implemented in Laos, which have led to the relocation of remote and dispersed populations into clustered villages with easier access to state services and market facilities. -

Highlights Highlights

© Lonely Planet Publications 343 L a o s HIGHLIGHTS Luang Prabang – enchanted mystical city of treasured wats, French cuisine and Indochinese villas overlooking the Mekong River ( p368 ) Luang Nam Tha and Muang Sing – taking eco-conscious treks into the feral jungle of Nam Ha National Protected Area and ethnic Akha villages ( p385 , p387 ) Si Phan Don – a lazy maze of shady islands and rocky islets, home to the rare Irrawaddy dolphin ( p400 ) Wat Phu Champasak – Khmer-era ruins perfectly placed beneath a mountain facing the peaceful riverside village of Champasak ( p399 ) Bolaven Plateau – home to the best coffee in Laos and dotted with ice-cold waterfalls to relieve the heat of the south ( p398) Off the beaten track – visiting Vieng Xai caves, the remote and forbidding home of Pathet Lao revolutionaries and the prison of the last king of Laos ( p382 ) FAST FACTS ATMs two in Vientiane, one in Luang Prabang, Vang Vieng and Pakse, all with international facilities Budget US$15 to US$20 a day Capital Vientiane Costs city guesthouse US$4-10, four-hour bus ride US$1.50, Beer Lao US$0.80 Country code %856 Languages Lao, ethnic dialects Money US$1 = 9627 kip Phrases sábąai-dii (hello), sábąai-dii (good- bye), khàwp jąi (thank you) Population 6.5 million Time GMT + seven hours Visas Thirty-day tourist visas are available arrival in Vientiane, Luang Prabang and in advance in Thailand, China, Vietnam or Pakse international airports, and when Cambodia. On-the-spot 30-day visas are crossing the border from Thailand, China available for US$30 with two photos on and Vietnam. -

Xaignabouli Province, Laos, January 2012 by Yuan

Road Trip with Child's Dream Laos Laos is beautiful. The people are very poor, yet so peaceful and friendly. Everywhere we go, everybody always carries a smile on the lips. Our trip takes me from Vientiane to Vang Vieng, Sainyabuli, Luang Prabang and then to the North of Laos. sunrise over Van Vieng We visit many different provinces, schools, education ministers and local communities. In some places, CD has already built a school so we're checking on the progress. In other areas, we are told that a school needs to be built/restored, so we pass by for an evaluation. Then again, we are meeting up with other NGOs to learn about potential collaboration possibilities in order to profit from synergies. There is also a lot of relationship-building that needs to be done with local government officials or village heads. It's a very diverse, busy trip filled with meetings, visits and talks. The schools that we visit are all completely different. There are primary schools, secondary schools and high schools... some schools consist of wooden piles and a few blades of grass on the roof. There are no tables, the students are squeezed together on some benches, the "blackboards" are filled with holes... and the teacher is often not present, the students study on their own. what do they do during rainy season, I wonder? Other schools have real walls and their own water filter system (which purifies the water from the wells, so that the children can drink it). The students wear pretty school uniforms, farm in their own garden (where they cultivate vegetables), play pétanque or volleyball and sip fresh young coconut juice (the coconuts grow in the school area).