Catalogue of the Wightman Memorial Art Gallery in the Library of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pope Francis on Flight from UAE Talks About Dialogue, War, Abuse

WWW.THEFLORIDACATHOLIC.ORG | Feb. 8-21, 2019 | Volume 80, Number 7 ORLANDO DIOCESE PALM BEACH DIOCESE VENICE DIOCESE A survivor’s faith story Catholic Schools Week WYD inspires teens Pope Francis on flight from UAE FEAST OF LOURDES talks about dialogue, war, abuse CINDY WOODEN Pope Francis also was asked about Catholic News Service the war in Yemen and about the con- ditions that would be necessary be- ABOARD THE PAPAL FLIGHT fore the Holy See would offer to me- FROM ABU DHABI, United Arab diate in the ongoing political crisis in Emirates | Pope Francis told re- Venezuela. porters he is more afraid of the con- On the question of intervening in sequences of not engaging in inter- Venezuela, Pope Francis said he had religious dialogue than he is of being been informed of the arrival by dip- manipulated by some Muslim lead- lomatic pouch of a letter from Ven- ers. ezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, He told reporters flying back to who is trying to hold on to power in Rome with him Feb. 5 from Abu Dha- Pope Francis aboard his flight from the country. bi that people are always saying he’s the United Arab Emirates, to Rome Asked if he was ready to mediate, letting himself be used by someone, Feb. 5. (PAUL HARING | CNS) Pope Francis said the Vatican would “including journalists, but it’s part of offer assistance only if both sides the job.” a while,” Pope Francis said. “We have requested its help and if both sides “For me, there is only one great suspended some priests, sent them showed a willingness to take steps danger at this moment: destruction, away for this, and -- I’m not sure if the toward resolving the crisis. -

Catholics Tired of Recurring Accusations of Clergy Sexual Abuse

VOL. 57, NO. 3 DIOCESE OF OAKLAND FEBRUARY 4, 2019 www.catholicvoiceoakland.org Serving the East Bay Catholic Community since 1963 Copyright 2019 Catholics tired of recurring accusations of clergy sexual abuse By Albert C. Pacciorini Staff writer A lively, respectful group of about 100 people met with two representatives of the Diocese of Oakland to discuss the issue of clergy sexual abuse and its coverup at St. Joan of Arc Church in San Ramon the evening of Jan. 22. Steve Wilcox, chancellor of the diocese, and Rev. Jayson Landeza outlined the historical issues of clergy sexual abuse while saying the evening would be mostly questions from the audience. Repeatedly, audience members drove home a theme: people, especially the young, are avoiding the Church in vast numbers, older people are falling away. They see the Church as unresponsive in meeting the needs of the gay and transgender community and not doing enough to end clergy sexual abuse. We’ve heard all this before, many said: People’s lives COURTESY PHOTO COURTESY have been ruined. Families are ruined. We’re tired of the About 50 people from St. Joseph Basilica, Alameda, were at the Walk for Life West Coast. Leading up to the apologies and repetition. Do something now.” walk, there were two hours a day for five days of Adoration for Life. On Jan. 26, about 30 walkers gathered Wilcox said he hopes the diocese can release its list at the basilica for a blessing prior to carpooling to BART and were joined by others at the walk. Walkers of credibly accused clergy on Feb. -

Selected Works Selected Works Works Selected

Celebrating Twenty-five Years in the Snite Museum of Art: 1980–2005 SELECTED WORKS SELECTED WORKS S Snite Museum of Art nite University of Notre Dame M useum of Art SELECTED WORKS SELECTED WORKS Celebrating Twenty-five Years in the Snite Museum of Art: 1980–2005 S nite M useum of Art Snite Museum of Art University of Notre Dame SELECTED WORKS Snite Museum of Art University of Notre Dame Published in commemoration of the 25th anniversary of the opening of the Snite Museum of Art building. Dedicated to Rev. Anthony J. Lauck, C.S.C., and Dean A. Porter Second Edition Copyright © 2005 University of Notre Dame ISBN 978-0-9753984-1-8 CONTENTS 5 Foreword 8 Benefactors 11 Authors 12 Pre-Columbian and Spanish Colonial Art 68 Native North American Art 86 African Art 100 Western Arts 264 Photography FOREWORD From its earliest years, the University of Notre Dame has understood the importance of the visual arts to the academy. In 1874 Notre Dame’s founder, Rev. Edward Sorin, C.S.C., brought Vatican artist Luigi Gregori to campus. For the next seventeen years, Gregori beautified the school’s interiors––painting scenes on the interior of the Golden Dome and the Columbus murals within the Main Building, as well as creating murals and the Stations of the Cross for the Basilica of the Sacred Heart. In 1875 the Bishops Gallery and the Museum of Indian Antiquities opened in the Main Building. The Bishops Gallery featured sixty portraits of bishops painted by Gregori. In 1899 Rev. Edward W. J. -

“Life of Washington” Mural the Importance Of

GEORGE WASHINGTON HIGH SCHOOL “LIFE OF WASHINGTON” MURAL TECHNICAL SOLUTIONS, BUILDING CONSENSUS, RESOURCES (Submitted to SFUSD on 4.17.19, updated 7.16.19) Over the past year, San Francisco Heritage (Heritage) has been researching examples of comparable mural and public art controversies across the country and solutions prescribed for addressing objectionable and offensive imagery. Heritage commissioned the City Landmark nomination for George Washington High School, co-authored by Donna Graves and Christopher VerPlanck, which comprehensively documents the school’s public art and architecture, including Victor Arnautoff’s “Life of Washington” (1936) mural. Heritage is closely following the public process concerning the “Life of Washington” mural, having attended three of the four Reflection and Action Group meetings convened by the school district in early 2019. Regardless of Arnautoff’s original intent, we recognize the offensive nature of the mural’s depictions and their impact on students, especially students of color. Our goal in compiling this memo is to provide a range of technical options for consideration by district officials in order to facilitate a constructive and unifying solution. George Washington High School is the latest in a series of controversies surrounding depictions of Native Americans, African Americans, and other historical events locally and nationally – frequently involving New Deal-era artworks. Although each case must be considered in its own context, taking into account the intent of the artist and how the imagery is experienced by contemporary viewers, there have been a range of creative approaches to remedying inaccurate, offensive, and/or stereotypical content in public art. All of the cases profiled below combine multiple responses to address the controversial historical depictions, including screening, interpretation, education, and/or new artwork to provide a contemporary perspective. -

Memorializing Knute Rockne at the University of Notre Dame: Collegiate Gothic Architecture and Institutional Identity Author(S): Sherry C

Memorializing Knute Rockne at the University of Notre Dame: Collegiate Gothic Architecture and Institutional Identity Author(s): Sherry C. M. Lindquist Source: Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 46, No. 1 (Spring 2012), pp. 1-24 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/665045 . Accessed: 05/11/2013 20:06 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Inc. are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Winterthur Portfolio. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 35.8.11.3 on Tue, 5 Nov 2013 20:06:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Memorializing Knute Rockne at the University of Notre Dame Collegiate Gothic Architecture and Institutional Identity Sherry C. M. Lindquist This article explores how the neo-Gothic building that was eventually built to commemorate Knute Rockne expresses a key moment in which the University of Notre Dame shaped its identity; it considers how the Knute Rockne Memorial Fieldhouse accordingly embodied and negotiated contradictory strains of manliness and civilization, populism and elitism, democracy and church authority. -

Notre Dame Scholastic, Vol. 20, No. 04

vV rj^ IX :^ ^rSGE-QMSI.SEHPER.YicTTIRTr$ -nn- QMSI • CB3S • HOSITURUsr. Vol.. XX. NOTRE DAME, INDIANA, SEPTEMBER 25, 18S6. No. 4. But Avhen the sun climbed up the sky. In the Desert. We drooped beneath its torrid rays, And knew, at last, thot Ave must die— We wandered long through pleasant vales, The sands beneath us AA^ere ablaze; And over simlit hillside slopes; The A'ery air seemed liquid flame; Each day Ave followed fairer trails, The earth a sea Avithout a shore; And each day i-ealized new Jiopes, We softly breathed the Father's name. And oft my dear companion said: Said one last prayer, and all Avas o'er. " Why should we leave this glorious land? Here let us bide till life has fled, Tlie stars that night their vigils kept And I'est content with joys at hand." Above tAvo corpses, ghastly Avhite; Yet knew not that tAvo spirits slept I had no thought of further gain. An endless sleep, more dark than night. Nor M-ished to find a fairer land; Rich were the vales and fair the slopes But rest to me was keenest pain; They left behind in discontent, Desires I could not understand And death the end of all their hopes I Still urged me on, until, at last, Who shall condemn their punishment.'' The desert wild before us lay; Yet thoughts of places we had passed Press on in eA-'ery noble strife, Could not restrain iny onward way. But folloAv not in pleasure's path If thou Avouldst lead a Christian life Forward I went. -

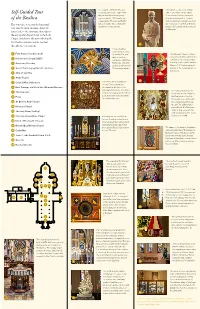

Self-Guided Tour of the Basilica

The magnificent Paul Fritts and St. André Bessette, C.S.C. (1845- Self-Guided Tour Company pipe organ, a gift of the 1937; canonized 2010), a Holy Wayne and Diana Murdy family, Cross brother, lived a simple and of the Basilica was installed in 2016 and boasts holy life and founded St. Joseph’s 4 keyboards, 70 stops and 5,164 Oratory, Montréal, Canada, out of his This tour takes you from the baptismal pipes. It stands 40 feet high and devotion to St. Joseph. Rev. Anthony weighs more than 20 tons. Lauck, C.S.C., designed the statue of font near the main entrance, down the St. Bessette. center aisle to the sanctuary, then right to the east apsidal chapels, back to the Lady Chapel, and then to the west-side chapels. 2 The Basilica museum may be reached 11 through the west transept. The gold ceiling marks the sanctuary 1 Font, Ambry, Paschal Candle of the Basilica, and The Reliquary Chapel contains depicts the four relics of most of the saints in the 2 Murdy Family Organ (2016) evangelists Matthew, calendar of the Liturgical Year, 3 Sanctuary Crossing Mark, Luke and John including a relic of Blessed Basil as well as various Old Moreau, C.S.C. (pictured here), 4 Seal of the Congregation of Holy Cross Testament prophets. founder of the Congregation of Holy Cross. 3 5 Altar of Sacrifice 6 Ambo (Pulpit) 12 7 Original Altar /Tabernacle The seal of the Congregation of Holy Cross, carved into 8 East Transept and World War I Memorial Entrance the marble at the front of the sanctuary, honors the spot where The Lady Chapel is known 9 Tintinnabulum Holy Cross religious profess their historically as the Chapel of perpetual vows and seminarians 10 Pietà the Exaltation of the Holy are ordained priests. -

2006-07 Softball 2006-07 University Of2006-07 University Notre Dame

2006-07 UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME SOFTBALL 2006-07 SOFTBALL 2006-07 UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME NOTRE 2006-07 UNIVERSITY OF Gessica Hufnagle SeniorSenior SOFTBALL Stephanie Brown SeniorSenior •• CaptainCaptain 2006 NFCA Second Team All-American 2006 First Team All- BIG EAST 2007 Notre Dame’s Softball Schedule Date Day Opponent Site Time Date Day Opponent Site Time February April Tiger Invitational, Feb. 16-18, Auburn, Ala 1 Sunday SYRACUSE* Notre Dame, Ind. 12 p.m. (DH) 16 Friday at Auburn Auburn, Ala. 3 p.m. 4 Wednesday VALPARAISO Notre Dame, Ind. 5 p.m. 16 Friday vs. UAB Auburn, Ala. 5:30 p.m. 5 Thursday DePaul* Chicago, Ill. 12 p.m. (DH) 17 Saturday vs. Tennessee Tech Auburn, Ala. (Field 2) 2 p.m. 10 Tuesday EASTERN MICHIGAN Notre Dame, Ind. 4 p.m. (DH) 17 Saturday vs. Tulsa Auburn, Ala. 5:30 p.m. 14 Saturday Providence* Providence, R.I. 12 p.m. (DH) 18 Sunday vs. Virginia Tech Auburn, Ala. 12:30 p.m. 15 Sunday Connecticut* Storrs, Conn. 12 p.m. (DH) 17 Tuesday WESTERN MICHIGAN Notre Dame, Ind. 3 p.m. (DH) Palm Springs Tournament, Feb 23-25, Palm Springs, Calif. 18 Wednesday BALL STATE Notre Dame, Ind. 5 p.m. 23 Friday vs. Oklahoma Palm Springs, Calif. 10 a.m. 21 Saturday LOUISVILLE* Notre Dame, Ind. 12 p.m. (DH) 23 Friday vs. California Palm Springs, Calif. 12:30 p.m. 22 Sunday SOUTH FLORIDA* Notre Dame, Ind. 12 p.m. (DH) 24 Saturday vs. UNLV Palm Springs, Calif. 10:30 a.m. 24 Tuesday NORTHWESTERN Notre Dame, Ind. -

A Father's Lesson, a Son's Gift

Olympic inspiration Columnist Christina Capecchi explains how the Olympic spirit is a needed virtue, page 12. Serving the Church in Central and Southern Indiana Since 1960 CriterionOnline.com August 12, 2016 Vol. LVI, No. 44 75¢ New Zika infection fears A father’s lesson, spark renewed debate on abortion a son’s gift WEST PALM BEACH, Fla. (CNS)—With a growing number of U.S. travelers returning from abroad with the Zika virus and with several cases of Zika-related microcephaly and birth defects reported in the U.S., the disease has inflamed the abortion debate domestically. U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio. a Republican from Miami, where the Zika virus has now started spreading in one neighborhood through mosquito transmission, said he does not believe the Zika virus should be a pretext for an infected pregnant woman to get an abortion. Rubio met in Miami on Sen. Marco Rubio Aug. 4 with Dr. Tom Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Florida’s Gov. Rick Scott. The senator also was making a renewed push to call the U.S. Congress back into session to approve funding for combating Zika domestically and to introduce legislation that would provide U.S. troops serving in high-risk areas with additional protections from Zika. He also reportedly told the news magazine Politico on Aug. 8: “Obviously, microcephaly is a terrible prenatal condition that kids are Brendan McCormick, left, and Johnny Malan had never met until a magical moment at an Indianapolis Indians’ baseball game earlier this year brought born with. -

099978-03 Imh June

Action, Agency, Affect Thomas Hart Benton’s Hoosier History ERIKA DOSS y longstanding interests as a cultural historian have repeatedly Mturned to issues of public popularity: to how and why certain kinds or styles of art become popular among the American public, how public tastes and preferences change, and how public popularity has affected and continues to affect the course of America’s visual cultures. By extension, they have focused on issues of cultural conflict and con- troversy—issues that are especially relevant in the story of Thomas Hart Benton’s 1933 mural, A Social History of the State of Indiana. Benton was the leader of the Regionalist art movement, a strain of American art that dominated from the late 1920s through the early 1940s, or the era of the Great Depression. He was probably the best- known American artist of the era: depicted on the cover of Time maga- zine in December 1934; often covered in the pages of Life magazine and other popular periodicals; and even selected in 1940 by the Divorce Reform League as one of America’s “best husbands” (along with President Franklin Delano Roosevelt).1 Benton’s brand of Regionalism __________________________ Erika Doss is professor in the Department of American Studies at the University of Notre Dame. This essay is adapted from her keynote address given at the conference “Thomas Hart Benton’s Indiana Murals at 75: Public Art and the Public University,” Indiana University, April 26, 2007. 1Henry Adams, Thomas Hart Benton: An American Original (New York, 1989), 299. INDIANA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY, 105 (June 2009) ᭧ 2009, Trustees of Indiana University. -

Softball Schedule February 12 (Fri.) (1) Vs

AleXia ClaY SENIOR UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME 2010 2010 SOFTBALL SCHEDULE February 12 (Fri.) (1) vs. Creighton Tempe, Ariz. 9:00 a.m. Softball (1) vs. Oregon Tempe, Ariz. 11:30 a.m. February 13 (Sat.) (1) vs. Auburn Tempe, Ariz. 4:30 p.m. (1) vs. Oregon State Tempe, Ariz. 7:00 p.m. February 14 (Sun.) (1) vs. Washington Tempe, Ariz. 10:30 a.m. February 20 (Sat.) (2) vs. Louisiana Tech Hattiesburg, Miss. 2:00 p.m. (2) at Southern Miss Hattiesburg, Miss. 7:00 p.m. February 21 (Sun.) (2) vs. Stephen F. Austin Hattiesburg, Miss. 9:00 a.m. (2) vs. Alcorn State Hattiesburg, Miss. 2:00 p.m. February 26 (Fri.) (3) vs. Lehigh Charlottesville, Va. 9:00 a.m. (3) vs. Ohio Charlottesville, Va. 11:30 a.m. February 27 (Sat.) (3) at Virginia Charlottesville, Va. 4:30 p.m. (3) vs. George Washington Charlottesville, Va. 7:00 p.m. February 28 (Sun.) (3) vs. Lehigh Charlottesville, Va. 11:30 a.m. March 6 (Sat.) (4) vs. Ohio State Riverside, Calif. 9:00 a.m. SOFTBALL DAME 2010 NOTRE (4) vs. East Tennessee State Riverside, Calif. 11:30 a.m. March 7 (Sun.) (4) at UC Riverside Riverside, Calif. 11:30 a.m. March 10 (Wed.) at Cal State Northridge Northridge, Calif. -- Katie FLEURY March 12 (Fri.) (5) vs. Buffalo Lakewood, Calif. 9:00 a.m. Junior • Team CapTain (5) vs. San Diego Lakewood, Calif. 11:15 a.m. March 13 (Sat.) (5) vs. UNLV Lakewood, Calif. 3:45 p.m. 2008 Third Team all-BiG EAST (5) vs. -

Diaspora Destiny: Joseph Jessing and Competing Narratives of Nation, 1860-1899

Diaspora Destiny: Joseph Jessing and Competing Narratives of Nation, 1860-1899 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Thomas Stefaniuk Graduate Program in Germanic Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Barbara Becker-Cantarino, Ph.D., Advisor Bernhard Malkmus, Ph.D. Carmen Taleghani-Nikazm, Ph.D. Copyright by Thomas Stefaniuk 2012 Abstract In what is increasingly considered a post-secular age, the role of religion in immigrants’ negotiations of transnational identities and search for national belonging is once again thought to be a significant one. The growing presence of Islamic diaspora communities in Europe and America has brought to the fore questions of how a “foreign” religious faith and heritage can be reconciled with the modern and secular – and yet latently Christian – cultures of their host countries. This dissertation attempts to contribute to this discourse by shedding light on a somewhat similar chapter in American and German migration and religious history. Returning to the so-called era of secularization in the late nineteenth century, I investigate the problem of how religion and nationalism were reconciled in a transnational context, namely in a German Catholic diaspora’s emerging construction of German-American identity. The vehicle for this analysis is the rhetoric of a leading opinion-shaper in the German-American Catholic community, Joseph Jessing, as it was performed in his leading German language Catholic newspaper, the Ohio Waisenfreund. Focusing on the print medium that was so crucial for the spread of ideas in the nineteenth century, I research almost thirty years of Jessing’s newspaper, as well as other German-American newspaper of the time, and place Jessing’s contribution to the diaspora group’s identity construction in the context of his day.