Undergraduate Dissertation Trabajo Fin De Grado

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction: Fairy Tale Films, Old Tales with a New Spin

Notes Introduction: Fairy Tale Films, Old Tales with a New Spin 1. In terms of terminology, ‘folk tales’ are the orally distributed narratives disseminated in ‘premodern’ times, and ‘fairy tales’ their literary equiva- lent, which often utilise related themes, albeit frequently altered. The term ‘ wonder tale’ was favoured by Vladimir Propp and used to encompass both forms. The general absence of any fairies has created something of a mis- nomer yet ‘fairy tale’ is so commonly used it is unlikely to be replaced. An element of magic is often involved, although not guaranteed, particularly in many cinematic treatments, as we shall see. 2. Each show explores fairy tale features from a contemporary perspective. In Grimm a modern-day detective attempts to solve crimes based on tales from the brothers Grimm (initially) while additionally exploring his mythical ancestry. Once Upon a Time follows another detective (a female bounty hunter in this case) who takes up residence in Storybrooke, a town populated with fairy tale characters and ruled by an evil Queen called Regina. The heroine seeks to reclaim her son from Regina and break the curse that prevents resi- dents realising who they truly are. Sleepy Hollow pushes the detective prem- ise to an absurd limit in resurrecting Ichabod Crane and having him work alongside a modern-day detective investigating cult activity in the area. (Its creators, Roberto Orci and Alex Kurtzman, made a name for themselves with Hercules – which treats mythical figures with similar irreverence – and also worked on Lost, which the series references). Beauty and the Beast is based on another cult series (Ron Koslow’s 1980s CBS series of the same name) in which a male/female duo work together to solve crimes, combining procedural fea- tures with mythical elements. -

Escapism and the Ideological Stance in Naomi Novik's

B R U M A L Revista de Investigación sobre lo Fantástico DOI: https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/brumal.606 Research Journal on the Fantastic Vol. VII, n.º 2 (otoño/autumn 2019), pp. 111-131, ISSN: 2014-7910 «I DIDN’T OFFER TO SHAKE HANDS; NO ONE WOULD SHAKE HANDS WITH A JEW»: ESCAPISM AND THE IDEOLOGICAL STANCE IN NAOMI NOVIK’S SPINNING SILVER SARA GONZÁLEZ BERNÁRDEZ Universidade de Santiago de Compostela [email protected] Recibido: 12-06-2019 Aceptado: 11-09-2019 AbsTRACT Naomi Novik, an American writer of Lithuanian-Polish ascendency, is one of the most acclaimed voices in contemporary young-adult fantasy fiction. Her fantasies are heav- ily influenced by her cultural heritage, as well as by the fairy tale tradition, which be- comes most obvious in her two standalone novels, Uprooted and the subject of this es- say, Spinning Silver. As the quote chosen for this essay’s title demonstrates, Novik’s second standalone work constitutes one of the most obvious outward statements of an ideological stance as expressed within fantasy literature, as well as an example of what Jack Zipes (2006) called transfiguration: the rewriting and reworking of traditional tales in order to convey a different, more subversive message. This paper considers how Novik’s retelling takes advantage of traditional fairy-tale elements to create an implicit critique of gender-based oppression, while at the same time, and much more overtly, denouncing racial and religious prejudice. The ideological stance thus conveyed is shown to be intended to have consequences for the reader and the world outside of the fiction. -

Read-Alike Catalog

2 0 2 0 • alike Catalog This catalog contains our recommendations for books that might appeal to readers who enjoyed Naomi Novik’s Spinning Silver. Spinning Silver (2018) by Naomi Novik Miryem is the daughter and grand- daughter of moneylenders, but her father’s inability to collect his debts has left his family on the edge of poverty— until Miryem takes matters into her own hands. Hardening her heart, the young woman sets out to claim what is owed and soon gains a reputation for being able to turn silver into gold. When an ill- advised boast draws the attention of the king of the Staryk—grim fey creatures who seem more ice than flesh—Miryem’s fate, and that of two kingdoms, will be forever altered. “A perfect tale . rich in both ideas and people, with the vastness of Tolkien and the empathy and joy in daily life of Le Guin.” — NY Times Book Review Uprooted (2015) by Naomi Novik “Moving, heartbreaking, and thoroughly satisfying, Uprooted is the fantasy novel I feel I've been waiting a lifetime for. Clear your schedule before picking it up, because you won't want to put it down.” — NPR “Uprooted is also part of the modern fairy-tale retelling tradition, because it is very much concerned with which stories get told, why and how they are told, and what truths might underlie them. That focus makes the novel not just exciting, but emotionally satisfying, and very much worthy of reading.” — TOR.com The Bear and the Nightingale (2017) by Katherine Arden “Arden’s supple, sumptuous first novel transports the reader to a version of medieval Russia where history and myth coexist. -

Children of Blood and Bone Named Audiobook of the Year at the 2019

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Danielle Katz, The Media Grind (818) 823-6603 Children of Blood and Bone named Audiobook of the Year at the 2019 Audie Awards Megan Mullally and Nick Offerman among others recognized last night for achievement in spoken word entertainment New York, NY – March 5, 2019 – The Audio Publishers Association (APA), the premiere trade organization of audiobooks and spoken word entertainment, announces today the winners of last night’s annual awards gala, The Audie Awards. The event was hosted by Queer Eye fashion expert, upcoming memoirist and audiobook narrator, Tan France, who lent his charming personality and delightful wit to the evening’s festivities. The Audies recognizes outstanding achievement from the authors, narrators, publishers, and producers of the most talked-about audiobooks in the industry. This year’s most prestigious award, Audiobook of the Year, has been named Tomi Adeyemi’s Children of Blood and Bone, published by Macmillan Audio. Recognized by the esteemed judging panel of Ron Charles (Book Critic for The Washington Post), Linda Holmes (Host of NPR's Pop Culture Happy Hour), and Lisa Lucas (Executive Director of the National Book Foundation), the Audiobook of the Year acknowledges the work that, through quality and influence, has caught the attention of the industry’s most important thought leaders. The panel praised Adeyemi’s work and Bahni Turpin’s captivating narration. “There's something magical about the timbre of Turpin’s voice that's perfectly tuned to the fantastical nature of this novel. I felt transported into the world of "Children of Blood and Bone," said Ron Charles. -

How Harry Potter Became the Boy Who Lived Forever

12/17/12 How Harry Potter Became the Boy Who Lived Forever ‑‑ Printout ‑‑ TIME Back to Article Click to Print Thursday, Jul. 07, 2011 The Boy Who Lived Forever By Lev Grossman J.K. Rowling probably isn't going to write any more Harry Potter books. That doesn't mean there won't be any more. It just means they won't be written by J.K. Rowling. Instead they'll be written by people like Racheline Maltese. Maltese is 38. She's an actor and a professional writer — journalism, cultural criticism, fiction, poetry. She describes herself as queer. She lives in New York City. She's a fan of Harry Potter. Sometimes she writes stories about Harry and the other characters from the Potterverse and posts them online for free. "For me, it's sort of like an acting or improvisation exercise," Maltese says. "You have known characters. You apply a set of given circumstances to them. Then you wait and see what happens." (See a Harry Potter primer.) Maltese is a writer of fan fiction: stories and novels that make use of the characters and settings from other people's professional creative work. Fan fiction is what literature might look like if it were reinvented from scratch after a nuclear apocalypse by a band of brilliant pop-culture junkies trapped in a sealed bunker. They don't do it for money. That's not what it's about. The writers write it and put it up online just for the satisfaction. They're fans, but they're not silent, couchbound consumers of media. -

The Tales of the Grimm Brothers in Colombia: Introduction, Dissemination, and Reception

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2012 The alest of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception Alexandra Michaelis-Vultorius Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the German Literature Commons, and the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Michaelis-Vultorius, Alexandra, "The alet s of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception" (2012). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 386. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. THE TALES OF THE GRIMM BROTHERS IN COLOMBIA: INTRODUCTION, DISSEMINATION, AND RECEPTION by ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2011 MAJOR: MODERN LANGUAGES (German Studies) Approved by: __________________________________ Advisor Date __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS 2011 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To my parents, Lucio and Clemencia, for your unconditional love and support, for instilling in me the joy of learning, and for believing in happy endings. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This journey with the Brothers Grimm was made possible through the valuable help, expertise, and kindness of a great number of people. First and foremost I want to thank my advisor and mentor, Professor Don Haase. You have been a wonderful teacher and a great inspiration for me over the past years. I am deeply grateful for your insight, guidance, dedication, and infinite patience throughout the writing of this dissertation. -

Program Schedule

Please Note: Class times, titles, and descriptionS may still change. WEDNESDAY SCHEDULE September 15th, 2021 CONFERENCE PREPARATION Meet the Agents, Publishers and Producers Taking Pitches at PNWA’s 66th Annual Conference. There will be a panel, followed by Spotlights on Tule Publishing and The Wild Rose Press. Agent, Editor, Publisher, and Producer Panel with Moderator Robert Dugoni and Judy Taylor 8:00 a.m. to 9:30 a.m. 9:00 a.m. to 10:30 a.m. 11:00 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. Spotlight On Publisher The Wild Rose Press with Moderator Pam Binder 10:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. 11:00 a.m. to Noon 1:00 p.m. to 2:00 p.m. Spotlight On Publisher Tule With Moderator Gerri Russell 11:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. 12:30 p.m. to 1:30 p.m. 2:30 p.m. – 3:30 p.m. -----------LUNCH BREAK------------- WORKSHOP 12:45 p.m. to 1:45 p.m. PDT 1:45 p.m. to 2:45 p.m. MDT 2:45 p.m. – 3:45 p.m. EDT Virtual Conference Do’s and Don’ts Ever wonder if there’s a certain etiquette you should be following at a professional conference? Does it apply in person as well as online? Join us and find out. Presenters: Pam Binder, Jennifer Douwes, Scott Douwes, Adam Russell, TBA Moderator: Pam Binder Updated August 30, 2021 1 Please Note: Class times, titles, and descriptionS may still change. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2:15 p.m. to 3:15 p.m. -

TESTIMONY of NAOMI NOVIK Before the Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property, and the Internet

TESTIMONY OF NAOMI NOVIK Before the Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property, and the Internet I’d like to thank the House Judiciary Committee for inviting me to testify about fair use and its role in promoting creativity. I am not a lawyer, but as one of the creators and artists whose work is deeply affected by copyright law, I hope to explain how vital fair use is to preserving our freedom and enabling us to create new and more innovative work. I urge Congress to not only preserve but strengthen fair use, to encourage still more innovation and creative work by more new artists. I would ask in particular that Congress consider improving protections for fair users, especially individual artists, who are threatened with lawsuits or DMCA takedowns. I. Fair use is vital to developing artists and creative communities. Today, I’m the author of ten novels including the New York Times bestselling Temeraire series, which has been optioned for the movies by Peter Jackson, the director of The Lord of the Rings. I’ve worked on professional computer games and graphic novels, and on both commercial and opensource software. I’m a founding member of the Organization of Transformative Works and served as its first President, and I’m one of the architects and programmers of the Archive of Our Own, home to nearly a million transformative works by individual writers and artists. And I would have done none of these things if I hadn’t begun by writing fanfiction. In 1994, while I was still in college, I first came across the online remix community. -

Fairy Tales in European Context Gen Ed Course Submission: for Inquiry – Humanitites

GER 103: Fairy Tales in European Context Gen Ed Course Submission: for Inquiry – Humanitites 2 lectures PLUS 1 discussion section: Professor Linda Kraus Worley 1063 Patterson Office Tower Phone: 257 1198 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Wednesdays 10 - 12; Fridays 10 – 12 and by appointment FOLKTALES AND FAIRY TALES entertain and teach their audiences about culture. They designate taboos, write out life scripts for ideal behaviors, and demonstrate the punishments for violating the collective and its prescribed social roles. Tales pass on key cultural and social histories all in a metaphoric language. In this course, we will examine a variety of classical and contemporary fairy and folktale texts from German and other European cultures, learn about approaches to folklore materials and fairy tale texts, and look at our own culture with a critical-historical perspective. We will highlight key issues, values, and anxieties of European (and U.S.) culture as they evolve from 1400 to the present. These aspects of human life include arranged marriage, infanticide, incest, economic struggles, boundaries between the animal and human, gender roles, and class antagonisms. Among the tales we will read and learn to analyze using various interpretive methods are tales collected by the Brothers Grimm, by the Italians Basile and Straparola, by seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French writers such as D‘Aulnoy, de Beaumont, and Perrault, by Hans Christian Andersen and Oscar Wilde. We will also read 20th century re-workings of classical fairy tale motifs. The course is organized around clusters of Aarne, Thompson and Uther‘s ―tale types‖ such as the Cinderella, Bluebeard, and the Hansel-and-Gretel tales. -

Five for Frightening Inside Prometheus: Prometheus Award the Keep: the Graphic Novel by F

Liberty and Culture Vol. 25, No. 1 Fall 2006 Five for frightening Inside Prometheus: Prometheus Award The Keep: The Graphic Novel By F. Paul Wilson, Art by Matthew Smith winners’ remarks; IDW, 2005/2006, Issues 1-5, $3.99 ea; WorldCon Report; Trade paperback $19.99 Reviews of fiction by Reviewed by Anders Monsen Gary Bennett, Keith Brooke, David Louis Edelman, The fourth incarnation of F. Paul Wilson’s 1980 horror Naomi Novik, novel, The Keep, appeared in five comic book format in- Ian MacDonald, stallments before being bound into trade paperback edition Chris Roberson; in August, 2006. Counting the novel, the other two ways you David Lloyd’s Kickback; can experience the story is through a feature film (VHS) and Movie review: a board game, although Wilson himself has disparaged the V for Vendetta film version of his novel, and labored for years to bring a new and truer version to the screen. What happens when Wilson writes his own visual script and finds an artist capable and willing to remain loyal to novel, yet also felt deliberately over-stylized. With The Keep: the story? First, to reduce a 332-page novel packed with The Graphic Novel, the roles are almost reversed; the stark ideas about power and mankind’s self-inflicted horrors sketches illuminate the pain of the characters (especially mixed with alien designs upon humanity into 110 pages Glaeken and Magda’s father), and the depth of Rasalom’s of sketches and brief dialog requires some sacrifices. A evil to a much greater degree than the novel. -

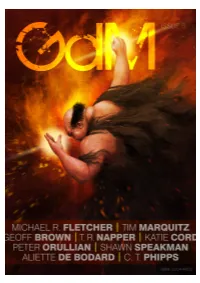

Grimdark-Magazine-Issue-6-PDF.Pdf

Contents From the Editor By Adrian Collins A Fair Man From The Vault of Heaven By Peter Orullian The Grimdark Villain Article by C.T. Phipps Review: Son of the Black Sword Author: Larry Correia Review by malrubius Excerpt: Blood of Innocents By Mitchell Hogan Publisher Roundtable Shawn Speakman, Katie Cord, Tim Marquitz, and Geoff Brown. Twelve Minutes to Vinh Quang By T.R. Napper Review: Dishonoured By CT Phipps An Interview with Aliette de Bodard At the Walls of Sinnlos A Manifest Delusions developmental short story by Michael R. Fletcher 2 The cover art for Grimdark Magazine issue #6 was created by Jason Deem. Jason Deem is an artist and designer residing in Dallas, Texas. More of his work can be found at: spiralhorizon.deviantart.com, on Twitter (@jason_deem) and on Instagram (spiralhorizonart). 3 From the Editor ADRIAN COLLINS On the 6th of November, 2015, our friend, colleague, and fellow grimdark enthusiast Kennet Rowan Gencks passed away unexpectedly. This one is for you, mate. Adrian Collins Founder Connect with the Grimdark Magazine team at: facebook.com/grimdarkmagazine twitter.com/AdrianGdMag grimdarkmagazine.com plus.google.com/+AdrianCollinsGdM/ pinterest.com/AdrianGdM/ 4 A Fair Man A story from The Vault of Heaven PETER ORULLIAN Pit Row reeked of sweat. And fear. Heavy sun fell across the necks of those who waited their turn in the pit. Some sat in silence, weapons like afterthoughts in their laps. Others trembled and chattered to anyone who’d spare a moment to listen. Fallow dust lazed around them all. The smell of old earth newly turned. -

CFP: Fairy Tales and Fantasy Fiction / Contes De Fées Et Fantasy

H-Portugal CFP: Fairy Tales and Fantasy Fiction / Contes de fées et Fantasy Discussion published by Viviane Bergue on Tuesday, September 7, 2021 Type: Call for Papers Date: October 25, 2021 Location: France Subject Fields: Literature, Film and Film History, Cultural History / Studies, Humanities In 1947, Tolkien published “On Fairy Stories”, an essay on fairy tales which grew out of his 1939 Andrew Lang Lecture and has since become the basis for the theorisation of the modern Fantasy genre. This essay popularised the terms secondary world, subcreation and subcreator in specialist criticism. Yet Tolkien’s text, often presented as being more a reflection on the author’s own literary conception and his Fantasy work, is indeed supposed to be about fairy tales and to offer a definition and presentation of their main characteristics, such as the notion of eucatastrophe, a concept coined by Tolkien to refer to the happy ending of fairy tales and which can be put into perspective with the naïve ethics of these tales, as examined by André Jolles in his book Simple Forms (1930). While it might therefore seem remarkable that Tolkien’s essay has become the basis for the theorisation of Fantasy, this is hardly surprising to Fantasy scholars, as Fantasy regularly borrows from the marvellous staff and structure of the fairy tale. It should not be forgotten that Tolkien himself considered The Lord of the Rings to be a fairy tale for adults and that his work is not free of elements and motifs from fairy tales. Moreover, the rewriting of fairy tales is recurrent within Fantasy to the point of having become an obligatory part of the genre for authors, willingly encouraged by publishers.