Hillsdale, a History by Herbert S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REPORTS of the TIBOR T. POLGAR FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM, 2013 David J. Yozzo, Sarah H. Fernald and Helena Andreyko Editors a Joint

REPORTS OF THE TIBOR T. POLGAR FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM, 2013 David J. Yozzo, Sarah H. Fernald and Helena Andreyko Editors A Joint Program of The Hudson River Foundation and The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation December 2015 ABSTRACT Eight studies were conducted within the Hudson River Estuary under the auspices of the Tibor T. Polgar Fellowship Program during 2013. Major objectives of these studies included: (1) reconstruction of past climate events through analysis of sedimentary microfossils, (2) determining past and future ability of New York City salt marshes to accommodate sea level rise through vertical accretion, (3) analysis of the effects of nutrient pollution on greenhouse gas production in Hudson River marshes, (4) detection and identification of pathogens in aerosols and surface waters of Newtown Creek, (5) detection of amphetamine type stimulants at wastewater outflow sites in the Hudson River, (6) investigating establishment limitations of new populations of Oriental bittersweet in Schodack Island State Park, (7) assessing macroinvertebrate tolerance to hypoxia in the presence of water chestnut and submerged aquatic species, and (8) examining the distribution and feeding ecology of larval sea lamprey in the Hudson River basin. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................................... iii Preface ................................................................................................................. vii Fellowship Reports Pelagic Tropical to Subtropical Foraminifera in the Hudson River: What is their Source? Kyle M. Monahan and Dallas Abbott .................................................................. I-1 Sea Level Rise and Sediment: Recent Salt Marsh Accretion in the Hudson River Estuary Troy D. Hill and Shimon C. Anisfeld .................................................................. II-1 Nutrient Pollution in Hudson River Marshes: Effects on Greenhouse Gas Production Angel Montero, Brian Brigham, and Gregory D. -

Designated Protected and Significant Areas of Dutchess County, NY

Chapter 7: Designated Significant and Protected Areas of Dutchess County (DRAFT) Chapter 7: Designated Protected and Significant Areas of Dutchess County, NY ______________________________________________________________________________ Emily Vail, Neil Curri, Noela Hooper, and Allison Chatrchyan1 February 2012 (DRAFT ) Significant natural areas are valued for their environmental importance Chapter Contents and beauty, and include unusual geologic features such as scenic Protected Land Critical Environmental mountain ridges, steep ravines, and caves; hydrological features such Areas as rivers, lakes, springs, and wetlands; and areas that support Other Significant Areas threatened or endangered species or unusually diverse plant and Implications for Decision- Making animal communities. Both significant natural areas and scenic Resources resources enhance the environmental health and quality of life in Dutchess County. An area can be significant for several different reasons, including its habitat, scenic, cultural, economic, or historical values. Many areas are significant because they are unique in some way. 1 This chapter was written by Emily Vail (Cornell Cooperative Extension Environment & Energy Program), Neil Curri (Cornell Cooperative Extension Dutchess County Environment & Energy Program), Noela Hooper (Dutchess County Department of Planning and Development), and Allison Chatrchyan (Cornell Cooperative Extension Dutchess County Environment & Energy Program). The chapter is presented here in DRAFT form. Final version expected March 2012. The Natural Resource Inventory of Dutchess County, NY 1 Chapter 7: Designated Significant and Protected Areas of Dutchess County (DRAFT) Significant natural areas provide many ecosystem services, including wildlife habitat, water supply protection, recreational space, and opportunities for outdoor research. (For more information on ecosystem services, see Chapter 1: Introduction.) In order to sustain their value, it is import to protect these areas. -

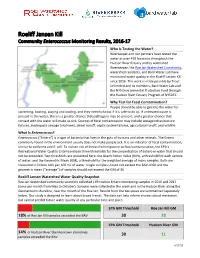

Roeliff Jansen Kill 2016

COMMUNITY WATER QUALITY MONITORING RESULTS ROELIFF JANSEN KILL 2016 OVERVIEW WATERSHED SNAPSHOT Riverkeeper and our partners have been testing These results are for non‐tidal sites only. the Hudson River and its tributaries for the As measured against the Environmental Protection fecal-indicator bacteria Enterococcus (“Entero”) Agency’s recommended Beach Action Value for safe since 2006. Sources of fecal contamination may swimming: include sewage infrastructure failures, sewer overflows, inadequate sewage treatment, septic system failures, agricultural runoff, urban 12% runoff, and wildlife. of Roeliff Jansen Kill samples failed. As measured against the EPA’s recommended In 2016, we began working with the Roe Jan geometric mean (GM, a weighted long‐term average) Watershed Community criterion for safe swimming: (www.roejanwatershed.org) and the Bard Water Lab to conduct testing in the Roeliff Jansen Kill. EPA GM threshold Roe Jan GM Samples were collected monthly (May to October) at 14 watershed locations by Roe Jan 30 24.8 Watershed Community members and local cells/100 mL cells/100 mL residents, and processed by the Bard Water Lab. A total of 84 samples were analyzed in 2016. This water quality monitoring study is designed 3 Best Sites 3 Worst Sites to learn about broad patterns and trends. The Livingston‐ Ancram‐ Hall Hill data can help inform choices about recreation in Above/Below Road Bridge (#6) the creek, but cannot predict future water Bingham Mills (#8, 9) Copake‐ Noster Kill quality at any particular time and place. Germantown‐ trib at Route 7A (#4) Sportsmen’s Club Ancram‐ Wiltsie All results will be available at (#10) Road Bridge fishing www.riverkeeper.org/water-quality/citizen- Hillsdale‐ Collins St access (#5) data/roeliff-jansen-kill soon. -

Before Albany

Before Albany THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Regents of the University ROBERT M. BENNETT, Chancellor, B.A., M.S. ...................................................... Tonawanda MERRYL H. TISCH, Vice Chancellor, B.A., M.A. Ed.D. ........................................ New York SAUL B. COHEN, B.A., M.A., Ph.D. ................................................................... New Rochelle JAMES C. DAWSON, A.A., B.A., M.S., Ph.D. ....................................................... Peru ANTHONY S. BOTTAR, B.A., J.D. ......................................................................... Syracuse GERALDINE D. CHAPEY, B.A., M.A., Ed.D. ......................................................... Belle Harbor ARNOLD B. GARDNER, B.A., LL.B. ...................................................................... Buffalo HARRY PHILLIPS, 3rd, B.A., M.S.F.S. ................................................................... Hartsdale JOSEPH E. BOWMAN,JR., B.A., M.L.S., M.A., M.Ed., Ed.D. ................................ Albany JAMES R. TALLON,JR., B.A., M.A. ...................................................................... Binghamton MILTON L. COFIELD, B.S., M.B.A., Ph.D. ........................................................... Rochester ROGER B. TILLES, B.A., J.D. ............................................................................... Great Neck KAREN BROOKS HOPKINS, B.A., M.F.A. ............................................................... Brooklyn NATALIE M. GOMEZ-VELEZ, B.A., J.D. ............................................................... -

This Article Was Originally Published in a Journal Published by Elsevier

This article was originally published in a journal published by Elsevier, and the attached copy is provided by Elsevier for the author’s benefit and for the benefit of the author’s institution, for non-commercial research and educational use including without limitation use in instruction at your institution, sending it to specific colleagues that you know, and providing a copy to your institution’s administrator. All other uses, reproduction and distribution, including without limitation commercial reprints, selling or licensing copies or access, or posting on open internet sites, your personal or institution’s website or repository, are prohibited. For exceptions, permission may be sought for such use through Elsevier’s permissions site at: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/permissionusematerial Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 71 (2007) 259e277 www.elsevier.com/locate/ecss Regional patterns and local variations of sediment distribution in the Hudson River Estuary F.O. Nitsche a,*, W.B.F. Ryan a, S.M. Carbotte a, R.E. Bell a, A. Slagle a, C. Bertinado a, R. Flood c, T. Kenna a, C. McHugh a,b a Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia Univeristy, Palisades, NY 10964, USA b Queens College, City University New York, Flushing, NY, USA c Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, USA Received 3 November 2005; accepted 27 July 2006 Available online 2 October 2006 Abstract The Hudson River Benthic Mapping Project, funded by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, resulted in a com- prehensive data set consisting of high-resolution multibeam bathymetry, sidescan sonar, and sub-bottom data, as well as over 400 sediment cores and 600 grab samples. -

Water-Quality Assessment of the Hudson River Basin in New York and Adjacent States −

Water-quality Assessment Of The Hudson River Basin In New York And Adjacent States − Analysis of available nutrient, pesticide, volatile organic compound, and suspended-sediment data, 1970-90 By Patrick J. Phillips and Dorothea W. Hanchar _____________________________________ U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 96-4065 Troy, New York 1996 i U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gordon Eaton, Director For additional information Copies of this report can be write to: purchased from: U.S. Geological Survey District Chief Branch of Information Services U.S. Geological Survey, WRD Federal Center 425 Jordan Road Box 25425 Troy, N.Y. 12180 Denver, CO 80225-8286 ii FOREWORD The mission of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) is to assess the quantity and quality of the earth resources of the Nation and to provide information that will assist resource managers and policymakers at Federal, State, and local levels in making sound decisions. Assessment of water-quality conditions and trends is an important part of this overall mission. One of the greatest challenges faced by water-resources scientists is acquiring reliable information that will guide the use and protection of the Nation's water resources. That challenge is being addressed by Federal, State, interstate, and local water-resource agencies and by many academic institutions. These organizations are collecting water-quality data for a host of purposes that include: compliance with permits and water-supply standards; development of remediation plans for a specific contamination problem; operational decisions on industrial, wastewater, or water-supply facilities; and research on factors that affect water quality. -

Resilient NY Program

1 Resilient NY Program October 29, 2019 Thomas R. Snow Jr. New York City Watershed and Flood Resiliency Programs 2 Resilient NY Program Flood/Ice Jam studies - • Includes 48 high-priority watersheds across NYS § Comprehensive hydrologic and hydraulic analysis (HEC-RAS) and ice jams (where applicable); § Fluvial geomorphic assessment; § Current and future flood flows due to climate change will be evaluated; and § Reports will include specific project recommendations to mitigate flooding and ice jams. 3 4 Hudson River Watershed - Wappinger Creek – Dutchess County Roeliff Jansen Kill – Dutchess/Columbia Main Street Brook – Ulster County Catskill Creek – Greene County Stockport Creek – Columbia/Rensselaer 5 How where these watersheds chosen? • # of Repetitive Losses/community (FEMA information). • # Repetitive Losses/stream (FEMA/DEC information); • Total $ flood insurance payment (FEMA information); • DEC technical staff; • Consultation with Departments of Homeland Security and EmerGency Services and State; and • County Soil and Water Conservation District staff. 6 Flooding - • An unfortunate reality in and near riverine areas across NYS • Most recent catastrophic floods 2006, 2011, 2012 and 2013 • Isolated storms § July 2017 – Town of Whitestown/Village of Whitesboro, Hoosick Falls • Ice jam flooding is also a common occurrence 7 Mohawk River Watershed Flooding • In 2013/14, completed 13 state-of- the-art flood studies completed in high priority watersheds § 4 - Oneida County § 8 – Herkimer § 1 – Montgomery • Schoharie Creek – initiated -

Roeliff Jansen Kill

Roeliff Jansen Kill Community Enterococcus Monitoring Results, 2016‐17 Who Is Testing the Water? Riverkeeper and our partners have tested the water at over 450 locations throughout the Hudson River Estuary and its watershed. Riverkeeper, the Roe Jan Watershed Community, watershed residents, and Bard Water Lab have monitored water quality in the Roeliff Jansen Kill since 2016. This work is made possible by Trout Unlimited and its members, Bard Water Lab and the NYS Environmental Protection Fund through the Hudson River Estuary Program of NYSDEC. Why Test for Fecal Contamination? People should be able to get into the water for swimming, boating, playing and wading, and they need to know if it is safe to do so. If untreated waste is present in the water, there is a greater chance that pathogens may be present, and a greater chance that contact with the water will make us sick. Sources of fecal contamination may include sewage infrastructure failures, inadequate sewage treatment, street runoff, septic system failures, agricultural runoff, and wildlife. What Is Enterococcus? Enterococcus (“Entero”) is a type of bacteria that lives in the guts of humans and other animals. The Entero commonly found in the environment usually does not make people sick. It is an indicator of fecal contamination, similar to coliforms and E. coli. To reduce risk of illness from exposure to fecal contamination, the EPA’s Recreational Water Quality Criteria include three thresholds for the concentration of Entero in water that should not be exceeded. Two thresholds are presented here: the Beach Action Value (BAV), a threshold for each sample of water; and the Geometric Mean (GM), a threshold for the weighted average of many samples. -

Wappingers Creek Watershed Management Plan

Natural Resource Management Plan For the Wappinger Creek Watershed Prepared by the: Dutchess County Environmental Management Council Dutchess County Soil and Water Conservation District Wappinger Creek Watershed Planning Committee Dutchess County Water Quality Strategy Committee With assistance from: Marist College Institute of Ecosystem Studies Dutchess County Department of Health Mid-Hudson Chapter of Trout Unlimited Cornell Cooperative Extension Dutchess County Land Use Law Center at Pace University School of Law YRDC-AmeriCorps Glynwood Center ImpAct, LLC Primary support was provided by: United States Environmental Protection Agency Wetlands Demonstration Grant Under Section 104 (b) (3) of the Clean Water Act NYS Department of Environmental Conservation Watershed Planning Grant under Section 319 of the Clean Water Act Rural New York Grant Program Dutchess County Staff for the project: Barbara Kendall, Executive Director, Dutchess County Environmental Management Council Edwin Hoxsie, Executive Director, Dutchess County Soil & Water Conservation District Dave Burns, Watershed Coordinator, DC Environmental Management Council Dalene Varney, Watershed Technician DC Environmental Management Council Bernadette Goebel, Program Assistant, DC Environmental Management Council Sarah Love, GIS Project Manager, DC Environmental Management Council Cara Stackpoole, GIS Technician, DC Environmental Management Council Meredith Hummel, Educator, DC Soil & Water Conservation District Amy DeGaetano, AEM Coordinator, DC Soil & Water Conservation District -

2014 Meeting Abstracts

PRESENTATION ABSTRACTS 2014 ANNUAL MEETING PROGRAM NEW YORK CHAPTER AMERICAN FISHERIES SOCIETY “Quantifying angler behavior: current practices and emerging methods ” February 5-7, 2014 Ramada Geneva Lakefront Geneva NY PLENARY What Can We Learn From The New York Statewide Angler Survey? Authors: Nancy A. Connelly 1, Shaun Keeler 2, and Barbara A. Knuth 1 Affiliations: 1: Human Dimensions Research Unit, Department of Natural Resources, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14850, 2: New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Bureau of Fisheries, 625 Broadway, Albany, NY 12233-4753 Presenter email: [email protected] Abstract: Since 1973 the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Bureau of Fisheries has conducted statewide angler surveys about every 10 years, with the most recent one in 2007. These large surveys, usually with an initial sample size of 17,000 or more, were designed primarily to provide fishery managers with information about angler effort on water bodies throughout the state. Having data on trends in fishing effort has been a particularly valuable outcome of these surveys. Efforts to improve the estimates of days fished have taken the form of several methods experiments conducted in conjunction with the statewide survey, including the use of angler diaries and reducing the recall period. Over the years additional questions have been added to the questionnaires to gauge angler opinions on various management issues, angler preferences for different types of fishing opportunities, level of satisfaction with the management agency, and angler awareness and knowledge of sport fish consumption advisories. However, because of the infrequent nature of the surveys they have not been particularly effective at providing feedback to managers from anglers on current or pressing management issues, other than at (or near) the actual year the statewide survey is conducted. -

How's the Water? Hudson River Water Quality and Water Infrastructure

HOW’S THE WATER? Hudson River Water Quality and Water Infrastructure The Hudson River Estuary is an engine of life for the coastal ecosystem, the source of drinking water for more than 100,000 people, home to the longest open water swim event in the world, and the central feature supporting the quality of life and $4.4 billion tourism economy for the region. This report focuses on one important aspect of protecting and improving Hudson River Estuary water quality – sewage-related contamination and water infrastructure. Untreated sewage puts drinking water and recreational users at risk. Water quality data presented here are based on analysis of more than 8,200 samples taken since 2008 from the Hudson River Estuary by Riverkeeper, CUNY Queens College, Columbia University’s Lamont- Doherty Earth Observatory; and from its tributaries by dozens of partner organizations and individual 21% community scientists. Water infrastructure information Hudson River Estuary samples presented here is based on data from the Department that failed to meet federal safe of Environmental Conservation and Environmental swimming guidelines Facilities Corporation, which administers State Revolving Funds. 44 Municipally owned wastewater While the Hudson River is safe for swimming at most treatment plants that locations on most days sampled, raw sewage overflows discharge to the Estuary and leaks from aging and failing infrastructure too often make waters unsafe. The Hudson’s tributaries $4.8 Billion – the smaller creeks and rivers that feed it – are often Investment needed in sources of contamination. wastewater infrastructure in the Hudson River Watershed To improve water quality, action is needed at the federal, state and local levels to increase and prioritize infrastructure investments. -

This Document Is Intended for Informational Use Only. Contact

***This document is intended for informational use only. Contact NYS DEC for regulations and accessibility*** Dutchess County Baxtertown Woods - 250 acres,upland and wetland forest communities, hunting, fishing, hiking, wildlife observation, and nature photography. Hunting access is from designated parking areas only. Big game hunting is restricted to bows and crossbows only. Rifles are prohibited. NOTE: The adjacent Stony Kill Farm Environmental Education Center remains closed to hunting and trapping. Depot Hill Multiple Use Area- This 260 acre multiple use area (MUA) is distinctive for hosting part of the Appalachian Trail. Located in the towns of Beekman and Pawling, there are several parking lots along the town road with unofficial trails for hiking and wildlife enjoyment. Possible recreational pursuits for this area include, hunting, hiking, wildlife and bird observation, and camping. Hudson Highlands State Park Preserve- Need permit from Parks office. Unlimited archery permits. Shotgun only- limited to the first 200 hunters. Big-game only. Lafayetteville Multiple Use Area- Lafayetteville Multiple Use Area consists of 715 acres in the Town of Milan, Dutchess County. This area has both fields and forests and is regularly stocked with pheasants during hunting season. Roeliff Jansen Kill Multiple Use Area-The Roeliff Jansen Kill Multiple Use Area consists of 128 acres in the Town of Milan, Dutchess County. Stissing Mountain Multiple Use Area- Stissing Mountain Multiple Use Area consists of 590 acres in the Tows of Milan, Pine Plains, and Stanford in Dutchess County. Taconic-Hereford Multiple Use Area- Taconic Hereford Mutiple Use Area consists of 917 acres located in the Towns of Pleasant Valley and LaGrange, Dutchess County.