Communication Model Fact Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marshall Mcluhan

Marshall McLuhan: Educational Implications* W.J. Gushue He received the Governor General's award for his work in literature, the Albert Schweitzer Chair at Fordham for his work in communications, and the Moison Award from the Canada Council as "explorer and interpreter of our age." He appeared on the covers of N eW8week, Saturday Review and Canada's largest weekend supplement. NBC made a one-hour docu mentary of his message and later repeated it, and the CBC gave him prime Sunday night viewing time on two occasions. He is one of the most publicized intellectuals of recent times. Ralph Thomas wrote in the Torfmto Star: "He has been explained, knocked and praised in just about every magazine in the EngIish, French, German and Italian languages." 1 As to newspaper coverage, which newspapers have not written about him? He has lectured city planners, advertising men, TV executives, university professors, students, and scientists; business men have sought his message from a yacht in the Aegean Sea, a hotel in the Laurentians, a former firehouse in San Francisco, and in the board rooms of IBM, General Electric, and Bell Telephone. Although "a torrent of criticism" has been heaped upon him by ':' Research for this paper was undertaken while Prof. Gushue was at the .ontario Institute for Studies in Education during the 1967-68 acad emic year. A slightly modified version was delivered at the C.A.P.E. conference in Calgary, June, 1968. - Ed. 3 4 Marshall McLuhan the old dogies of academe and the literary establishment, he has been eulogized in dozens of scholarly magazines and studied serious ly by thousands of intellectuals.2 The best indication of his worth is the fact that among his followers are to be found people (artists, really) who are part of what Susan Sontag calls "the new sensibility." 3 They are, to use Louis Kronenberger's phrase, "the symbol manipulators," the peo ple who are calling the shots - painters, sculptors, publishers, pub lic relations men, architects, film-makers, musicians, designers, consultants, editors, T.V. -

Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies

Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies Working with Autism Spectrum Disorders & Related Communication & Social Skill Challenges Linda Hodgdon, M.Ed., CCC-SLP Speech-Language Pathologist Consultant for Autism Spectrum Disorders [email protected] Learning effective conversation skills ranks as one of the most significant social abilities that students with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) need to accomplish. Educators and parents list the challenges: “Steve talks too much.” “Shannon doesn’t take her turn.” “Aiden talks when no one is listening.” “Brandon perseverates on inappropriate topics.” “Kim doesn’t respond when people try to communicate with her.” The list goes on and on. Difficulty with conversation prevents these students from successfully taking part in social opportunities. What makes learning conversation skills so difficult? Conversation requires exactly the skills these students have difficulty with, such as: • Attending • Quickly taking in and processing information • Interpreting confusing social cues • Understanding vocabulary • Comprehending abstract language Many of those skills that create skillful conversation are just the ones that are difficult as a result of the core deficits in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Think about it. From the student’s point of view, conversation can be very puzzling. Conversation is dynamic. .fleeting. .changing. .unpredictable. © Linda Hodgdon, 2007 1 All Rights Reserved This article may not be duplicated, -

Roth Book Notes--Mcluhan.Pdf

Book Notes: Reading in the Time of Coronavirus By Jefferson Scholar-in-Residence Dr. Andrew Roth Mediated America Part Two: Who Was Marshall McLuhan & What Did He Say? McLuhan, Marshall. The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man. (New York: Vanguard Press, 1951). McLuhan, Marshall and Bruce R. Powers. The Global Village: Transformations in World Life and Media in the 21st Century. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989). McLuhan, Marshall. The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1962). McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994. Originally Published 1964). The Mechanical Bride: The Gutenberg Galaxy Understanding Media: The Folklore of Industrial Man by Marshall McLuhan Extensions of Man by Marshall by Marshall McLuhan McLuhan and Lewis H. Lapham Last week in Book Notes, we discussed Norman Mailer’s discovery in Superman Comes to the Supermarket of mediated America, that trifurcated world in which Americans live simultaneously in three realms, in three realities. One is based, more or less, in the physical world of nouns and verbs, which is to say people, other creatures, and things (objects) that either act or are acted upon. The second is a world of mental images lodged between people’s ears; and, third, and most importantly, the mediasphere. The mediascape is where the two worlds meet, filtering back and forth between each other sometimes in harmony but frequently in a dissonant clanging and clashing of competing images, of competing cultures, of competing realities. Two quick asides: First, it needs to be immediately said that Americans are not the first ever and certainly not the only 21st century denizens of multiple realities, as any glimpse of Japanese anime, Chinese Donghua, or British Cosplay Girls Facebook page will attest, but Americans first gave it full bloom with the “Hollywoodization,” the “Disneyfication” of just about anything, for when Mae West murmured, “Come up and see me some time,” she said more than she could have ever imagined. -

Digital Rhetoric: Toward an Integrated Theory

TECHNICAL COMMUNICATION QUARTERLY, 14(3), 319–325 Copyright © 2005, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Digital Rhetoric: Toward an Integrated Theory James P. Zappen Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute This article surveys the literature on digital rhetoric, which encompasses a wide range of issues, including novel strategies of self-expression and collaboration, the characteristics, affordances, and constraints of the new digital media, and the forma- tion of identities and communities in digital spaces. It notes the current disparate na- ture of the field and calls for an integrated theory of digital rhetoric that charts new di- rections for rhetorical studies in general and the rhetoric of science and technology in particular. Theconceptofadigitalrhetoricisatonceexcitingandtroublesome.Itisexcitingbe- causeitholdspromiseofopeningnewvistasofopportunityforrhetoricalstudiesand troublesome because it reveals the difficulties and the challenges of adapting a rhe- torical tradition more than 2,000 years old to the conditions and constraints of the new digital media. Explorations of this concept show how traditional rhetorical strategies function in digital spaces and suggest how these strategies are being reconceived and reconfiguredDo within Not these Copy spaces (Fogg; Gurak, Persuasion; Warnick; Welch). Studies of the new digital media explore their basic characteris- tics, affordances, and constraints (Fagerjord; Gurak, Cyberliteracy; Manovich), their opportunities for creating individual identities (Johnson-Eilola; Miller; Turkle), and their potential for building social communities (Arnold, Gibbs, and Wright; Blanchard; Matei and Ball-Rokeach; Quan-Haase and Wellman). Collec- tively, these studies suggest how traditional rhetoric might be extended and trans- formed into a comprehensive theory of digital rhetoric and how such a theory might contribute to the larger body of rhetorical theory and criticism and the rhetoric of sci- ence and technology in particular. -

Securities Whistleblowing Under Dodd-Frank: Neglecting the Power of “Enterprising Privateers” in Favor of the “Slow-Going Public Vessel”

Do Not Delete 2/14/2012 1:27 PM SECURITIES WHISTLEBLOWING UNDER DODD-FRANK: NEGLECTING THE POWER OF “ENTERPRISING PRIVATEERS” IN FAVOR OF THE “SLOW-GOING PUBLIC VESSEL” by Michael Neal∗ This Note analyzes the SEC whistleblower program, as modified by the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010. It reviews the history of whistleblowing-like statutes in the United States and analyzes the successes and failures of prior whistleblowers after dividing them into two mutually exclusive groups: Insiders, those who are employed by the company against whom they report; and Outsiders, non-employees. The Note concludes that the new SEC whistleblower program is deficient in two ways. First, it does not create an affirmative duty for Insiders to internally report when their employer has a functioning compliance department; and second, Outsiders lack an offensive private cause of action granting them standing to sue on behalf of the SEC. The Note recommends changes to the program that resolve these deficiencies and better align the SEC’s required functions with its resources. The Note concludes that, as enacted, the SEC whistleblower program encourages the avoidance of internal corporate compliance systems, externalizes corporate compliance to a regulatory body already struggling to provide adequate oversight, weakens the partnership between the regulator and the regulated, and has the potential of reversing the positive progression in corporate cultures developed over the past decade. I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................... 1108 II. U.S. INFORMANT PROGRAMS ................................................. 1110 A. Stealing from the Government—The False Claims Act ................ 1110 B. The IRS Informant Program—“The Reward for Rats” ............... 1114 C. The SEC Informant Program ................................................... -

Sherron Watkins and Whistle Blowing at Enron Ethics of 3

BUSINESS Cases in Corporate Ethics: Contemporary Challenges and Imperatives; Strategy & General Management, Ethics and Social Justice, Organizational Behavior, Human Resource, Operations, Finance and Accounting, Marketing and Sales. Case 2.3: Sherron Watkins and Whistle Blowing at Enron Ozzie Mascarenhas SJ, PhD DRD Tata Chair Professor of Business Ethics, XLRI Jamshedpur, India | Published: June 2015 | Redistribution or use without the expressed, written permission of The Global Jesuit Case Series is prohibited. For information on usage rights, contact the Global Jesuit Case Series at [email protected] ________________________________________________________________________ Cases in Corporate Ethics: Contemporary Challenges and Imperatives Jesuit Series, Madden School of Business, Le Moyne College, Syracuse, NY Donated by: Ozzie Mascarenhas SJ, PhD JRD Tata Chair Professor of Business Ethics, XLRI, Jamshedpur, India June 15, 2015 The fifteen cases in Business ethics included here represent the first installment of the thirty cases promised to the Cases in Business Ethics – The Jesuit Series at the University of Le Moyne, Syracuse, NY. We have added three more. The remaining eighteen cases will follow shortly. The thirty three cases illustrate and depend upon the content of corporate ethics outlined in Table 1. As might be clear from Table I, the Course in Corporate Ethics has three parts: Part One explores the ethical quality of moral agents embedded in the capitalist markets such as the human person, the fraud-prone person, the virtuous actor (virtue ethics) and the trusting executive (ethics of trust). Part Two investigates the ethical quality of moral agencies of executive decisions, choices and actions when supported by ethics of critical thinking, moral reasoning, ethics of rights and duties, and ethics of moral leadership. -

A Guide to Radio Communications Standards for Emergency Responders

A GUIDE TO RADIO COMMUNICATIONS STANDARDS FOR EMERGENCY RESPONDERS Prepared Under United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the European Commission Humanitarian Office (ECHO) Through the Disaster Preparedness Programme (DIPECHO) Regional Initiative in Disaster Risk Reduction March, 2010 Maputo - Mozambique GUIDE TO RADIO COMMUNICATIONS STANDARDS FOR EMERGENCY RESPONDERS GUIDE TO RADIO COMMUNICATIONS STANDARDS FOR EMERGENCY RESPONDERS Table of Contents Introductory Remarks and Acknowledgments 5 Communication Operations and Procedures 6 1. Communications in Emergencies ...................................6 The Role of the Radio Telephone Operator (RTO)...........................7 Description of Duties ..............................................................................7 Radio Operator Logs................................................................................9 Radio Logs..................................................................................................9 Programming Radios............................................................................10 Care of Equipment and Operator Maintenance...........................10 Solar Panels..............................................................................................10 Types of Radios.......................................................................................11 The HF Digital E-mail.............................................................................12 Improved Communication Technologies......................................12 -

The Complexity of Richness: Media, Message, and Communication Outcomes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of North Carolina at Greensboro The complexity of richness: Media, message, and communication outcomes By: Robert F. Otondo, James R. Van Scotter, David G. Allen, Prashant Palvia Otondo, R.F., Van Scotter, J.R., Allen, D.G., and Palvia, P. ―The Complexity of Richness: Media, Message, and Communication Outcomes.‖ Information & Management. Vol. 40, 2008, pp. 21-30. Made available courtesy of Elsevier: http://www.elsevier.com ***Reprinted with permission. No further reproduction is authorized without written permission from Elsevier. This version of the document is not the version of record. Figures and/or pictures may be missing from this format of the document.*** Abstract: Dynamic web-based multimedia communication has been increasingly used in organizations, necessitating a better understanding of how it affects their outcomes. We investigated factor structures and relationships involving media and information richness and communication outcomes using an experimental design. We found that these multimedia contexts were best explained by models with multiple fine-grained constructs rather than those based on one- or two-dimensions. Also, media richness theory poorly predicted relationships involving these constructs. Keywords: Media richness theory; Information richness; Communication theory Article: 1. Introduction Investigation of relationships between the media and communication effectiveness has not provided consistent results. However, lack of understanding has not deterred organizations from investing heavily in new and dynamic forms of web-based multimedia for their marketing, public relations, training, and recruiting activities. Few studies have examined the effects of media channels and informational content on decision-making and other organizational outcomes. -

Writing Systems Reading and Spelling

Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems LING 200: Introduction to the Study of Language Hadas Kotek February 2016 Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Outline 1 Writing systems 2 Reading and spelling Spelling How we read Slides credit: David Pesetsky, Richard Sproat, Janice Fon Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems What is writing? Writing is not language, but merely a way of recording language by visible marks. –Leonard Bloomfield, Language (1933) Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems Writing and speech Until the 1800s, writing, not spoken language, was what linguists studied. Speech was often ignored. However, writing is secondary to spoken language in at least 3 ways: Children naturally acquire language without being taught, independently of intelligence or education levels. µ Many people struggle to learn to read. All human groups ever encountered possess spoken language. All are equal; no language is more “sophisticated” or “expressive” than others. µ Many languages have no written form. Humans have probably been speaking for as long as there have been anatomically modern Homo Sapiens in the world. µ Writing is a much younger phenomenon. Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems (Possibly) Independent Inventions of Writing Sumeria: ca. 3,200 BC Egypt: ca. 3,200 BC Indus Valley: ca. 2,500 BC China: ca. 1,500 BC Central America: ca. 250 BC (Olmecs, Mayans, Zapotecs) Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems Writing and pictures Let’s define the distinction between pictures and true writing. -

Former Enron Vice President Sherron Watkins on the Enron Collapse

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Former Enron vice president Sherron Watkins on the Enron collapse Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9pb4r7nj Journal Academy of Management Executive, 17(4) ISSN 1079-5545 Author Pearce, JL Publication Date 2003 DOI 10.5465/ame.2003.11851888 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ? Academy of Management Executive, 2003, Vol. 17, No. 4 Former Enron vice president Sherron Watkins on the Enron collapse Academy Address, August 3, 2003, by Sherron Watkins Introduction to the address by Academy President Jone L. Pearce It is my pleasure to introduce Sherron Watkins, the Academy of Management's 2003 Distinguished Executive Speaker. By now, her story as the former vice president of Enron Corporation who tried to bring what she called "an elaborate accounting hoax" to the attention of Enron's chief executive officer is well known. In August 2001, responding to his invitation to employees to put any concerns in a comment box, she did so. When he did not address her explosive charges at a subsequent company-wide meeting, she sought a face-to-face meeting with him. A month later the CEO announced to employees that "our financial liquidity has never been stronger," while exercising his own $1.5 billion in stock options, just ahead of the company's announcement of a $618 million quarterly loss. When United States Congressional investigators uncovered her letter buried in boxes of documents, they brought Ms. Watkins before the United States Senate in February 2002 to testify about her warnings. -

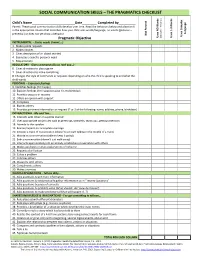

Social Communication Skills – the Pragmatics Checklist

SOCIAL COMMUNICATION SKILLS – THE PRAGMATICS CHECKLIST Child’s Name Date .Completed by . Words Preverbal) Parent: These social communication skills develop over time. Read the behaviors below and place an X - 3 in the appropriate column that describes how your child uses words/language, no words (gestures – - Language preverbal) or does not yet show a behavior. Present Not Uses Complex Uses Complex Gestures Uses Words NO Uses 1 Pragmatic Objective ( INSTRUMENTAL – States needs (I want….) 1. Makes polite requests 2. Makes choices 3. Gives description of an object wanted 4. Expresses a specific personal need 5. Requests help REGULATORY - Gives commands (Do as I tell you…) 6. Gives directions to play a game 7. Gives directions to make something 8. Changes the style of commands or requests depending on who the child is speaking to and what the child wants PERSONAL – Expresses feelings 9. Identifies feelings (I’m happy.) 10. Explains feelings (I’m happy because it’s my birthday) 11. Provides excuses or reasons 12. Offers an opinion with support 13. Complains 14. Blames others 15. Provides pertinent information on request (2 or 3 of the following: name, address, phone, birthdate) INTERACTIONAL - Me and You… 16. Interacts with others in a polite manner 17. Uses appropriate social rules such as greetings, farewells, thank you, getting attention 18. Attends to the speaker 19. Revises/repairs an incomplete message 20. Initiates a topic of conversation (doesn’t just start talking in the middle of a topic) 21. Maintains a conversation (able to keep it going) 22. Ends a conversation (doesn’t just walk away) 23. -

Unit – 1 Overview of Optical Fiber Communication

www.getmyuni.com Optical Fiber Communication 10EC72 Unit – 1 Overview of Optical Fiber communication 1. Historical Development Fiber optics deals with study of propagation of light through transparent dielectric waveguides. The fiber optics are used for transmission of data from point to point location. Fiber optic systems currently used most extensively as the transmission line between terrestrial hardwired systems. The carrier frequencies used in conventional systems had the limitations in handling the volume and rate of the data transmission. The greater the carrier frequency larger the available bandwidth and information carrying capacity. First generation The first generation of light wave systems uses GaAs semiconductor laser and operating region was near 0.8 μm. Other specifications of this generation are as under: i) Bit rate : 45 Mb/s ii) Repeater spacing : 10 km Second generation i) Bit rate: 100 Mb/s to 1.7 Gb/s ii) Repeater spacing: 50 km iii) Operation wavelength: 1.3 μm iv) Semiconductor: In GaAsP Third generation i) Bit rate : 10 Gb/s ii) Repeater spacing: 100 km iii) Operating wavelength: 1.55 μm Fourth generation Fourth generation uses WDM technique. i) Bit rate: 10 Tb/s ii) Repeater spacing: > 10,000 km Iii) Operating wavelength: 1.45 to 1.62 μm Page 5 www.getmyuni.com Optical Fiber Communication 10EC72 Fifth generation Fifth generation uses Roman amplification technique and optical solitiors. i) Bit rate: 40 - 160 Gb/s ii) Repeater spacing: 24000 km - 35000 km iii) Operating wavelength: 1.53 to 1.57 μm Need of fiber optic communication Fiber optic communication system has emerged as most important communication system.