Landscape No. 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My New Cover.Pptx

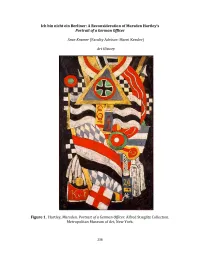

Ich bin nicht ein Berliner: A Reconsideration of Marsden Hartley's Portrait of a German Officer Sean Kramer (FacultyAdvisor: Marni Kessler) Art History Figure I7 8artley9 Marsden7 Portrait of a German Officer. Alfred ;tie<lit= >ollection7 Metro?olitan Museum of Art9 New York. 236 German Officer with a formal analysis of This painting, executed in November 1914, the painting. I then use semiotic theory to shows Hartley's assimilation of both Cubism begin to unpack notions of a singular, (the collagelike juxtapositions of visual fragments) and German Expressionism (the "correct" interpretation of the painting coarse brushwork and dramatic use of bright and to emphasize the multiform nature of colors and black). In 1916 the artist denied that reception. In this section, I seek to the objects in the painting had any special establish that the artist's personal meaning (perhaps as a defensive measure to connection to the artwork is not ward off any attacks provoked by the intense anti-German sentiment in America at the time). necessarily the most important However, his purposeful inclusion of medals, interpretive guideline for working with banners, military insignia, the Iron Cross, and this image. I then use examples of letters the German imperial flag does invoke a specific and numerals within the work to sense of Germany during World War I as well illustrate the plurality of cultural and as a collective psychological and physical linguistic processes which inform portrait of a particular officer.1 viewership of the painting. Meanings in a text, I posit, rely on the interaction between the contexts of the viewer and of This quotation comes from a section the author. -

Marsden Hartley on Cape Ann : Hartley’S 16 Year Relationship with Cape Ann Lecture Transcript

MARSDEN HARTLEY ON CAPE ANN : HARTLEY’S 16 YEAR RELATIONSHIP WITH CAPE ANN LECTURE TRANSCRIPT Speaker: Elyssa East Date: 8/18/2012 Runtime: 0:56:10 Camera Operator: unknown Identification: VL46 ; Video Lecture #46 Citation: East, Elyssa. “Marsden Hartley on Cape Ann : Hartley’s 16 Year Relationship with Cape Ann.” CAM Video Lecture Series, 8/18/2012. VL46, Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, MA. Copyright: Requests for perMission to publish Material from this collection should be addressed to the Librarian/Archivist. Language: English Finding Aid: Video Description: 2012 Press Release Subject List: Trudi Olivetti, 6/24/2020 Transcript: Linda Berard, 4/15/2020. Video Description FroM 2012 Press Release: In 1931, the AMerican Early Modernist painter Marsden Hartley spent a life-altering suMMer in Dogtown. But Hartley had a long-standing relationship with Cape Ann that began years earlier. Elyssa East, author of Dogtown: Death and Enchantment in a New England Ghost Town, will discuss Hartley's sixteen-year relationship with Cape Ann and how it Marsden Hartley on Cape Ann – VL46 – page 2 changed his life and work. “Marsden Hartley on Cape Ann” is offered in conjunction with the special exhibition Marsden Hartley: Soliloquy in Dogtown, which is on display at the Cape Ann MuseuM through October 14. The lecture is generously sponsored by the Cape Ann Savings Bank. Elyssa East is the author of Dogtown: Death and Enchantment in a New England Ghost Town, which won the 2010 P.E.N. New England/L. L. Winship award in Nonfiction. A Boston Globe bestseller, Dogtown was named a “Must-Read Book” by the Massachusetts Book Awards and an Editors’ Choice Selection of the New York TiMes Sunday Book Review. -

Cubism in America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1985 Cubism in America Donald Bartlett Doe Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Part of the Art and Design Commons Doe, Donald Bartlett, "Cubism in America" (1985). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. RESOURCE SERIES CUBISM IN SHELDON MEMORIAL ART GALLERY AMERICA Resource/Reservoir is part of Sheldon's on-going Resource Exhibition Series. Resource/Reservoir explores various aspects of the Gallery's permanent collection. The Resource Series is supported in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. A portion of the Gallery's general operating funds for this fiscal year has been provided through a grant from the Institute of Museum Services, a federal agency that offers general operating support to the nation's museums. Henry Fitch Taylor Cubis t Still Life, c. 19 14, oil on canvas Cubism in America .".. As a style, Cubism constitutes the single effort which began in 1907. Their develop most important revolution in the history of ment of what came to be called Cubism art since the second and third decades of by a hostile critic who took the word from a the 15th century and the beginnings of the skeptical Matisse-can, in very reduced Renaissance. -

The Influence of Gertrude Stein on Marsden Hartley’S Approach to the Object Portrait Genre Christal Hensley

One Portrait of One Woman: The Influence of Gertrude Stein on Marsden Hartley’s Approach to the Object Portrait Genre Christal Hensley Marsden Hartley’s 1916 painting One Portrait of One Woman Hartley’s circle that assembled abstract and/or symbolic forms is an object portrait of the American abstractionist poet and in works called “portraits.”4 writer Gertrude Stein (Figure 1). Object portraits are based on Although several monographs address Stein’s impact on an object or a collage of objects, which through their associa- Hartley’s object portraits, none explores the formal aspects of tion evoke the image of the subject in the title. In this portrait, this relationship.5 This paper first argues that Hartley’s initial the centrally located cup is set upon an abstraction of a checker- approach to the object portrait genre developed independently board table, placed before a half-mandorla of alternating bands of that of other artists in his circle. Secondly, this discussion of yellow and white, and positioned behind the French word posits that Hartley’s debt to Stein was not limited to her liter- moi. Rising from the half-mandorla is a red, white and blue ary word portraits of Picasso and Matisse but extended to her pattern that Gail Scott reads as an abstraction of the Ameri- collection of “portraits” of objects entitled Tender Buttons: can and French flags.1 On the right and left sides of the can- Objects, Food, Rooms, published in book form in 1914. And vas are fragments of candles and four unidentified forms that finally, this paper concludes that Hartley’s One Portrait of echo the shape of the half-mandorla. -

The Alterity of the Readymade: Fountain and Displaced Artists in Wartime

THE ENDURING IMPACT OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR A collection of perspectives Edited by Gail Romano and Kingsley Baird The Alterity of the Readymade: Fountain and Displaced Artists in Wartime Marcus Moore Massey University Abstract In April 1917, a porcelain urinal titled Fountain was submitted by Marcel Duchamp (or by his female friend, Louise Norton) under the pseudonym ‘R. MUTT’, to the Society of Independent Artists in New York. The Society’s committee refused to show it in their annual exhibition of some 2,125 works held at the Grand Central Palace. Eighty-seven years later, in 2004, Fountain was voted the most influential work of art in the 20th century by a panel of world experts. We inherit the 1917 work not because the original object survived—it was thrown out into the rubbish—but through a photographic image that Alfred Steiglitz was commissioned to take. In this photo, Marsden Hartley’s The Warriors, painted in 1913 in Berlin, also appears, enlisted as the backdrop for the piece of American hardware Duchamp selected from a plumbing showroom. To highlight the era of the Great War and its effects of displacement on individuals, this article considers each subject in turn: Marcel Duchamp’s departure from Paris and arrival in New York in 1915, and Marsden Hartley’s return to New York in 1915 after two years immersing himself in the gay subculture in pre-war Berlin. As much as describe the artists’ experiences of wartime, explain the origin of the readymade and reconstruct the events of the notorious example, Fountain, the aim of this article is to additionally bring to the fore the alterity of the other item imported ready-made in the photographic construction—the painting The Warriors. -

AMERICAN MODERNIST MASTERWORKS PROVIDE a DISTINCT FOCUS THIS DECEMBER at CHRISTIE's NEW YORK Important American Paintings

For Immediate Release November 9, 2005 Contact: Rik Pike 212.636.2680 [email protected] AMERICAN MODERNIST MASTERWORKS PROVIDE A DISTINCT FOCUS THIS DECEMBER AT CHRISTIE’S NEW YORK Important American Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture December 1, 2005 New York – Christie’s Fall 2005 sale of Important American Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture will take place on Thursday December 1 in the Galleries at Rockefeller Center. Featuring 148 lots, the auction features an exemplary array of Modernist works, including masterpieces by Stuart Davis, John Marin, Marsden Hartley and Max Weber - and three lots consigned by The Museum of Modern Art. The sale is expected to realize in excess of $25 million. The American modernist market has been gaining considerable strength in recent seasons. With the rapid growth in the post- war and contemporary market, collectors who traditionally have bought in this category are showing increased interest in American modernism, an essential precursor to the international post-war art movements. Christie’s auction offers such buyers an excellent opportunity to further develop their own collections in this field. The modernist works are led by Still Life with Flowers by Stuart Davis (estimate: $2,000,000- 3,000,000). A student of Robert Henri and an early proponent of the Ashcan School, Davis was one of the first American painters to embrace Modernism after his encounter with the European avant- garde at the ground-breaking Armory Show of 1913 in New York. After raising enough money after his first one-man show at the Downtown Gallery in 1927, Davis traveled to Paris. The trip galvanized his new visual aesthetic, combining his abstract exploration with forms inspired by Parisian façades and streets. -

Hartley, Marsden (1877-1943) by Ken Gonzales-Day

Hartley, Marsden (1877-1943) by Ken Gonzales-Day Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com A central figure in the evolution of modern American art, Marsden Hartley was also among a handful of gay and lesbian artists who came to define the delicate balance between the poetic and the erotic in the early days of the American avant-garde. He was born Edmund Hartley in Lewiston, Maine in 1877. His mother died when he was only eight years old, an event that may have haunted him his entire life. Certainly, death was to be the occasion of many of his most memorable paintings. In 1889, four years after the death of his mother, Hartley's farther married Martha Marsden, whose maiden name the painter was to adopt as his first name in 1906. From 1898 to 1904, Hartley studied at the Cleveland School of Art, the New York School of Marsden Hartley (top, in Art, and the National Academy of Design. 1939) painted Portrait of a German Officer (1914, above) as a memorial to In 1909, Hartley landed his first major exhibition at Alfred Stieglitz's highly respected a friend and an New York gallery, gallery 291, followed by a second exhibition in 1912. In that same expression of forbidden year, like many artists of his generation, he made a pilgrimage to Paris, where he met passion. the well-known art collectors Leo and Gertrude Stein. Photographic portrait of Marsden Hartley by Carl van Vechten, June 7, In 1913, Hartley visited Berlin and Munich, where he met artists Franz Marc and 1939. -

RESOURCE GUIDE American Moderns, 1910-1960: from O’Keeffe to Rockwell Was Organized by the Brooklyn Museum

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986). 2 Yellow Leaves (Yellow Leaves), 1928. Oil on canvas, 40 x 30 1/8 in. (101.6 x 76.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Georgia O’Keeffe, 87.136.6. RESOURCE GUIDE American Moderns, 1910-1960: From O’Keeffe to Rockwell was organized by the Brooklyn Museum. AMERICAN MODERNS, 1910—1960: FROM O’KEEFFE TO ROCKWELL 01 “One cannot be an American by going about saying that one is an American. It is necessary to feel America, like America, love America and then work.” Georgia O’Keeffe, 1926 Detail: George Wesley Bellows (American, 1882-1925). The Sand Cart, 1917. Oil on canvas. Brooklyn Museum, John B. Woodward Memorial Fund, 24.85 AMERICAN MODERNS, 1910–1960: TABLE OF CONTENTS FROM O‘KEEFFE TO ROCKWELL 1 Exhibition Introduction September 27, 2012–January 6, 2013 2 Cubist Experiments The five decades from 1910 to 1960 witnessed tumultuous and widespread 3 The Still Life Revisited changes in American society. As the United States assumed international prominence as an economic, industrial, and military superpower, it also faced the 4 Nature Essentialized difficulties of wars and the Great Depression. New technologies altered all aspects of modern life, and a diverse and mobile population challenged old 5 Modern Structures social patterns and clamored for the equality and opportunities promised by the American dream. 6 Engaging Characters These dramatic social and technological changes inform the paintings and sculptures from the world-renowned collection of the Brooklyn Museum in 7 Americana American Moderns, 1910—1960: From O’Keeffe to Rockwell. In seeking new ways 8 Reading Lists to make their work relevant to contemporary audiences, many American artists rejected long-standing artistic traditions of realism and narrative and 11 Lessons Plans reformulated the genres of figure painting, landscape, and still life. -

Marsden Hartley: the German Paintings 1913–1915 on View: August 3–November 30, 2014 Location: BCAM, Level 2

^ Exhibition advisory Exhibition: Marsden Hartley: The German Paintings 1913–1915 On View: August 3–November 30, 2014 Location: BCAM, Level 2 (Image captions on p age 4) The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) presents Marsden Hartley: The German Paintings 1913–1915 (August 3–November 30, 2014), the first focused look and the first solo exhibition on the West Coast in almost ten years of the American-born artist’s German paintings in the United States. From 1912 to 1915, Hartley lived in Europe—first in Paris and then in Berlin. There he developed a singular style that reflected his modern surroundings and the tumultuous time before and during World War I. Berlin’s exciting urban environment, prominent gay community, and military spectacle had a profound impact upon him. Marsden Hartley features approximately 25 paintings from this critical moment in Hartley’s career that reveal dynamic shifts in style and subject matter comprised of musical and spiritual abstractions, city portraits, and military symbols to Native American motifs. "The timing of this exhibition at LACMA is right, as it coincides with the centennial anniversary of World War I and the period in which Hartley made these paintings," says Michael Govan, LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director. "It also affords our visitors a unique opportunity to see three different exhibitions looking at art made in Germany made in and around this era: in addition to Marsden Hartley , LACMA is also presenting Expressionism in Germany and France: Van Gogh to Kandinsky through September 14; and on September 21 will open Haunted Screens: German Cinema in the 1920s ." “This is the first exhibition focused on Hartley’s Berlin paintings in the United States,” says Stephanie Barron, senior curator and department head of modern art at LACMA. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

REREADING ALFRED STIEGLITZ’S EQUIVALENTS By NICOLE E. SOUKUP A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2009 1 © 2009 Nicole E. Soukup 2 To my family 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my committee—Dr. Eric Segal, Dr. Shepherd Steiner and Dr. Alex Alberro—for their guidance and insight as I developed my ideas. Molly Bloom at the National Gallery of Art, deserves special recognition for her assistance viewing a selection of the Equivalents series. I am indebted to the librarians at the Cooper Hewitt Library, part of the Smithsonian Institute, New York City, and at the University of Florida. My editors—Amy C. Rieke and Sheila Bishop—made sure my writing was clear and concise. I especially am grateful to my friends and family for their support and encouragement. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...............................................................................................................4 ABSTRACT.....................................................................................................................................6 CHAPTER 1 REREADING ALFRED STIEGLITZ’S EQUIVALENTS .......................................................8 Introduction...............................................................................................................................8 The Equivalents ........................................................................................................................9 -

Hartley, Marsden American, 1877 - 1943

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS American Paintings, 1900–1945 Hartley, Marsden American, 1877 - 1943 Alfred Stieglitz, Marsden Hartley, 1916, platinum print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection BIOGRAPHY Marsden Hartley was born on January 4, l877, in Lewiston, Maine, to English immigrant parents. In 1893 he moved with his family to Ohio, where he studied at the Cleveland School of Art. Hartley took private lessons with John Semon, a Barbizon-style painter, and in 1898 he took a summer class with Cullen Yates, a local impressionist. Hartley excelled at the Cleveland School of Art, and a trustee provided him with financial backing to study in New York for five years. He moved to Manhattan in 1899 and attended William Merritt Chase’s School of Art before transferring to the National Academy of Design. In 1902, after Hartley won the Academy’s Suydam Silver Medal for still-life drawing, he spent the summer painting landscapes in Center Lovell, Maine. During the summer of 1907 in Eliot, Maine, Hartley attended a retreat for mystics called Green Acre, where he immersed himself in the study of Eastern religions. In 1908 he went to Boston and met Maurice Prendergast (American, 1858 - 1924), whose neoimpressionist style influenced his Maine landscapes. A major turning point in the artist’s career occurred in 1909, when Hartley was introduced to the photographer and art impresario Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864 - 1946), who arranged a one-man exhibition at his 291 gallery. With the financial support of Stieglitz and Arthur B. Davies (American, 1862 - 1928), Hartley traveled to Paris in 1912 and encountered the work of Paul Cézanne (French, 1839 - 1906), Henri Matisse (French, 1869 - 1954), and Pablo Picasso Hartley, Marsden 1 © National Gallery of Art, Washington National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS American Paintings, 1900–1945 (Spanish, 1881 - 1973), along with other French modernists at the home of the prominent American collectors Gertrude and Leo Stein. -

How Do YOU Spotlight? Spotlight 2015–16 Marsden Hartley, Portrait Arrangement

How do YOU Spotlight? Spotlight 2015–16 Marsden Hartley, Portrait Arrangement Watch the Spotlight Video Hear from teachers and students who participated in Spotlight and see past projects at mcnayart.org/spotlight. Schedule an Optional Classroom Visit Prior to beginning your Spotlight project, schedule a classroom visit from a McNay educator. The visit includes in-depth looking at a reproduction of the Spotlight selection and an art historical background of the artist and the work of art. Students learn how to look closely and theorize about the style or content of the work of art supported by visual evidence. Plan a Free Student Tour A museum visit is the best way to prepare for Spotlight. On a free student tour, students closely examine the Spotlight selection in person and consider how and why it was made with the help of a museum docent. For more information on student tours, visit mcnayart.org/tours. Learn about the Artist Conduct your own research about the artist and the work of art online or with your campus librarian. The McNay Library is also an excellent resource. Brainstorm Project Ideas Spotlight projects can take on many forms and are not limited to art making, with past submissions including painting and sculpture, but also poetry and film. The goal is to respond to the work of art in a creative way. That could be a science experiment, a choreographed dance, or a video game. Execute Your Idea Spotlight encourages experimentation. Students learn problem solving skills as they experiment, evaluate the results, and adapt their approach.