Marsden Hartley: from Maine to Dogtown and Back Again Lecture Finding Aid & Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stuart Davis (1892–1964) by Lisa Bush Hankin

fine art as an investment Stuart Davis (1892–1964) by Lisa Bush Hankin leading member of the first genera- with a current record auction price of four and family friends Robert Henri (1865–1929) and tion of artists who put a distinctly a half million dollars (Fig. 1). John Sloan (1871–1951), whose early artistic A American spin on the modernist ideas Born in Philadelphia, Davis was the son of support enabled the young man to participate then percolating in Europe, Stuart Davis is cel- professional artists (a sculptor and the art in prominent exhibitions including the ebrated for his lively and colorful canvases that director for the Philadelphia Press), who relo- groundbreaking 1913 Armory Show, an event incorporate imagery from the American pop- cated to northern New Jersey, outside New that profoundly affected the direction his art ular culture of his day. Davis is seen as a York City, when Davis was nine. Davis bene- would take. Though Davis’ early works reflect seminal figure in early modernism, and his fited early in his career from the guidance of the influence of the Ashcan school (Fig. 2), he works are highly sought after by both museums soon chose to depart from representing his and collectors. As a result, his major paintings Stuart Davis subjects in an illusionistic manner, dispensing Record Prices for Work at Auction do not appear on the market very frequently, with 3-dimensional form in favor of using and — as back-to-back multimillion dollar Present $4,500,000 line, color, and pattern to capture the energy 2005 $2,400,000 sales at Sotheby’s and Christie’s in the fall of Fig. -

My New Cover.Pptx

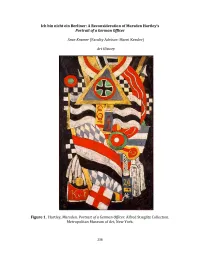

Ich bin nicht ein Berliner: A Reconsideration of Marsden Hartley's Portrait of a German Officer Sean Kramer (FacultyAdvisor: Marni Kessler) Art History Figure I7 8artley9 Marsden7 Portrait of a German Officer. Alfred ;tie<lit= >ollection7 Metro?olitan Museum of Art9 New York. 236 German Officer with a formal analysis of This painting, executed in November 1914, the painting. I then use semiotic theory to shows Hartley's assimilation of both Cubism begin to unpack notions of a singular, (the collagelike juxtapositions of visual fragments) and German Expressionism (the "correct" interpretation of the painting coarse brushwork and dramatic use of bright and to emphasize the multiform nature of colors and black). In 1916 the artist denied that reception. In this section, I seek to the objects in the painting had any special establish that the artist's personal meaning (perhaps as a defensive measure to connection to the artwork is not ward off any attacks provoked by the intense anti-German sentiment in America at the time). necessarily the most important However, his purposeful inclusion of medals, interpretive guideline for working with banners, military insignia, the Iron Cross, and this image. I then use examples of letters the German imperial flag does invoke a specific and numerals within the work to sense of Germany during World War I as well illustrate the plurality of cultural and as a collective psychological and physical linguistic processes which inform portrait of a particular officer.1 viewership of the painting. Meanings in a text, I posit, rely on the interaction between the contexts of the viewer and of This quotation comes from a section the author. -

Exhibition Image Captions

Contacts: Mike Brice Stephanie Elton EXHIBITION Public Relations Specialist Director of Communications IMAGE CAPTIONS 419-255-8000 x7301 419-255-8000 x7428 [email protected] [email protected] Life Is a Highway: Art and American Car Culture 1. Don Eddy (American, born 1944), Red Mercedes. Color lithograph, 1972. 24 1/8 x 30 11/16 in. (61.3 x 78 cm). Toledo Museum of Art (Toledo, Ohio), Frederick B. and Kate L. Shoemaker Fund, 1974.36. © Don Eddy Image Credit: Christopher Ridgway 2. Robert Indiana (American, 1928–2018), South Bend. Color lithograph, 1978. 30 x 27 15/16 in. (76.2 x 71 cm). Toledo Museum of Art, Gift of Art Center, Inc., 1978.63. © Morgan Art Foundation Ltd. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 3. Claes Oldenburg (American, born Sweden, 1929), Profile Airflow. Cast polyurethane relief over two-color lithograph, 1969. 33 1/4 x 65 1/2 x 3 3/4 in. (84.5 x 166.4 x 9.5 cm). Collection of the Flint Institute of Arts, Flint, MI; Museum purchase. © 1969 Claes Oldenburg 1 of 3 4. Kerry James Marshall (American, born 1955), 7am Sunday Morning. Acrylic on canvas banner, 2003. 120 x 216 in. (304.8 x 548.6 cm). Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Joseph and Jory Shapiro Fund by exchange, 2003.16. © Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. 5. Helen Levitt (American, 1913–2009), New York City (Spider Girl). Chromogenic color print, 1980. 12 1/4 × 18 in. (31.1 × 45.7 cm). Toledo Museum of Art, Purchased with funds from the Frederick B. -

Marsden Hartley on Cape Ann : Hartley’S 16 Year Relationship with Cape Ann Lecture Transcript

MARSDEN HARTLEY ON CAPE ANN : HARTLEY’S 16 YEAR RELATIONSHIP WITH CAPE ANN LECTURE TRANSCRIPT Speaker: Elyssa East Date: 8/18/2012 Runtime: 0:56:10 Camera Operator: unknown Identification: VL46 ; Video Lecture #46 Citation: East, Elyssa. “Marsden Hartley on Cape Ann : Hartley’s 16 Year Relationship with Cape Ann.” CAM Video Lecture Series, 8/18/2012. VL46, Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, MA. Copyright: Requests for perMission to publish Material from this collection should be addressed to the Librarian/Archivist. Language: English Finding Aid: Video Description: 2012 Press Release Subject List: Trudi Olivetti, 6/24/2020 Transcript: Linda Berard, 4/15/2020. Video Description FroM 2012 Press Release: In 1931, the AMerican Early Modernist painter Marsden Hartley spent a life-altering suMMer in Dogtown. But Hartley had a long-standing relationship with Cape Ann that began years earlier. Elyssa East, author of Dogtown: Death and Enchantment in a New England Ghost Town, will discuss Hartley's sixteen-year relationship with Cape Ann and how it Marsden Hartley on Cape Ann – VL46 – page 2 changed his life and work. “Marsden Hartley on Cape Ann” is offered in conjunction with the special exhibition Marsden Hartley: Soliloquy in Dogtown, which is on display at the Cape Ann MuseuM through October 14. The lecture is generously sponsored by the Cape Ann Savings Bank. Elyssa East is the author of Dogtown: Death and Enchantment in a New England Ghost Town, which won the 2010 P.E.N. New England/L. L. Winship award in Nonfiction. A Boston Globe bestseller, Dogtown was named a “Must-Read Book” by the Massachusetts Book Awards and an Editors’ Choice Selection of the New York TiMes Sunday Book Review. -

Swing Landscape

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS American Paintings, 1900–1945 Stuart Davis American, 1892 - 1964 Study for "Swing Landscape" 1937-1938 oil on canvas overall: 55.9 × 73 cm (22 × 28 3/4 in.) framed: 77.8 × 94.6 × 7 cm (30 5/8 × 37 1/4 × 2 3/4 in.) Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase and exchange through a gift given in memory of Edith Gregor Halpert by the Halpert Foundation and the William A. Clark Fund) 2014.79.15 ENTRY Swing Landscape [fig. 1] was the first of two commissions that Stuart Davis received from the Mural Division of the Federal Art Project (FAP), an agency of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), to make large-scale paintings for specific sites in New York. The other was Mural for Studio B, WNYC, Municipal Broadcasting Company [fig. 2]. [1] The 1930s were a great era of mural painting in the United States, and Davis, along with such artists as Thomas Hart Benton (American, 1889 - 1975), Arshile Gorky (American, born Armenia, c. 1902 - 1948), and Philip Guston (American, born Canada, 1913 - 1980), was an important participant. In the fall of 1936, Burgoyne Diller (American, 1906 - 1965), the head of the Mural Division and a painter in his own right, convinced the New York Housing Authority to commission artists to decorate some basement social rooms in the Williamsburg Houses, a massive, new public housing project in Brooklyn. A dozen artists were chosen to submit work, and, while Davis’s painting was never installed, it turned out to be a watershed in his development. -

2010-2011 Newsletter

Newsletter WILLIAMS G RADUATE PROGRAM IN THE HISTORY OF A RT OFFERED IN COLLABORATION WITH THE CLARK ACADEMIC YEAR 2010–11 Newsletter ••••• 1 1 CLASS OF 1955 MEMORIAL PROFESSOR OF ART MARC GOTLIEB Letter from the Director Greetings from Williamstown! Our New features of the program this past year include an alumni now number well over 400 internship for a Williams graduate student at the High Mu- going back nearly 40 years, and we seum of Art. Many thanks to Michael Shapiro, Philip Verre, hope this newsletter both brings and all the High staff for partnering with us in what promises back memories and informs you to serve as a key plank in our effort to expand opportuni- of our recent efforts to keep the ties for our graduate students in the years to come. We had a thrilling study-trip to Greece last January with the kind program academically healthy and participation of Elizabeth McGowan; coming up we will be indeed second to none. To our substantial community of alumni heading to Paris, Rome, and Naples. An ambitious trajectory we must add the astonishingly rich constellation of art histori- to be sure, and in Rome and Naples in particular we will be ans, conservators, and professionals in related fields that, for a exploring 16th- and 17th-century art—and perhaps some brief period, a summer, or on a permanent basis, make William- sense of Rome from a 19th-century point of view, if I am al- stown and its vicinity their home. The atmosphere we cultivate is lowed to have my way. -

Cubism in America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1985 Cubism in America Donald Bartlett Doe Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Part of the Art and Design Commons Doe, Donald Bartlett, "Cubism in America" (1985). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. RESOURCE SERIES CUBISM IN SHELDON MEMORIAL ART GALLERY AMERICA Resource/Reservoir is part of Sheldon's on-going Resource Exhibition Series. Resource/Reservoir explores various aspects of the Gallery's permanent collection. The Resource Series is supported in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. A portion of the Gallery's general operating funds for this fiscal year has been provided through a grant from the Institute of Museum Services, a federal agency that offers general operating support to the nation's museums. Henry Fitch Taylor Cubis t Still Life, c. 19 14, oil on canvas Cubism in America .".. As a style, Cubism constitutes the single effort which began in 1907. Their develop most important revolution in the history of ment of what came to be called Cubism art since the second and third decades of by a hostile critic who took the word from a the 15th century and the beginnings of the skeptical Matisse-can, in very reduced Renaissance. -

HARD FACTS and SOFT SPECULATION Thierry De Duve

THE STORY OF FOUNTAIN: HARD FACTS AND SOFT SPECULATION Thierry de Duve ABSTRACT Thierry de Duve’s essay is anchored to the one and perhaps only hard fact that we possess regarding the story of Fountain: its photo in The Blind Man No. 2, triply captioned “Fountain by R. Mutt,” “Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz,” and “THE EXHIBIT REFUSED BY THE INDEPENDENTS,” and the editorial on the facing page, titled “The Richard Mutt Case.” He examines what kind of agency is involved in that triple “by,” and revisits Duchamp’s intentions and motivations when he created the fictitious R. Mutt, manipulated Stieglitz, and set a trap to the Independents. De Duve concludes with an invitation to art historians to abandon the “by” questions (attribution, etc.) and to focus on the “from” questions that arise when Fountain is not seen as a work of art so much as the bearer of the news that the art world has radically changed. KEYWORDS, Readymade, Fountain, Independents, Stieglitz, Sanitary pottery Then the smell of wet glue! Mentally I was not spelling art with a capital A. — Beatrice Wood1 No doubt, Marcel Duchamp’s best known and most controversial readymade is a men’s urinal tipped on its side, signed R. Mutt, dated 1917, and titled Fountain. The 2017 centennial of Fountain brought us a harvest of new books and articles on the famous or infamous urinal. I read most of them in the hope of gleaning enough newly verified facts to curtail my natural tendency to speculate. But newly verified facts are few and far between. -

The Influence of Gertrude Stein on Marsden Hartley’S Approach to the Object Portrait Genre Christal Hensley

One Portrait of One Woman: The Influence of Gertrude Stein on Marsden Hartley’s Approach to the Object Portrait Genre Christal Hensley Marsden Hartley’s 1916 painting One Portrait of One Woman Hartley’s circle that assembled abstract and/or symbolic forms is an object portrait of the American abstractionist poet and in works called “portraits.”4 writer Gertrude Stein (Figure 1). Object portraits are based on Although several monographs address Stein’s impact on an object or a collage of objects, which through their associa- Hartley’s object portraits, none explores the formal aspects of tion evoke the image of the subject in the title. In this portrait, this relationship.5 This paper first argues that Hartley’s initial the centrally located cup is set upon an abstraction of a checker- approach to the object portrait genre developed independently board table, placed before a half-mandorla of alternating bands of that of other artists in his circle. Secondly, this discussion of yellow and white, and positioned behind the French word posits that Hartley’s debt to Stein was not limited to her liter- moi. Rising from the half-mandorla is a red, white and blue ary word portraits of Picasso and Matisse but extended to her pattern that Gail Scott reads as an abstraction of the Ameri- collection of “portraits” of objects entitled Tender Buttons: can and French flags.1 On the right and left sides of the can- Objects, Food, Rooms, published in book form in 1914. And vas are fragments of candles and four unidentified forms that finally, this paper concludes that Hartley’s One Portrait of echo the shape of the half-mandorla. -

HETAG: the Houston Earlier Texas Art Group

HETAG: The Houston Earlier Texas Art Group Jack Key Flanagan [Townscape] c.1946 HETAG Newsletter November/December 2017 Here it is almost the end of another year. Yes, they do fly by, but there’s no time to dwell on that. As you will see later in the newsletter, planning is already well underway on a number of fronts for exciting HETAG, CASETA and other exhibitions, gatherings and publications in 2018 relating to Earlier Houston and Early Texas Art. Stay tuned for another exciting year. The newsletter image theme for this issue: Works by some Earlier Houston Artists you may never have heard of. Plus a recreation of a special Emma Richardson Cherry exhibition at the end. Charles Allyn Gordon [Farmhouse] c.1935-1940 (l); Florence B. Grant Winter in Houston c.1943 (r) HETAG: The Houston Earlier Texas Art Group Upcoming HETAG meeting: Our next HETAG meeting will be a visit to Betty Moody Gallery 2815 Colquitt St., Houston Sunday January 7, 2018, at 2:30 p.m. Betty will welcome us for a look at the amazing paintings by Sarah Williams Sarah Williams Abilene 2017 Oil on Board 18x24 And the end-of-year gallery artist group exhibition. There will be lots of fun and fascinating stories about the Houston art scene going back a few years, as only Betty can tell them. Michael Kennaugh Beyond Delta 2017 (l); Lucas Johnson La Entrada 1977 (r) Jim Love Ash Tray/Candle Holder 1957 HETAG: The Houston Earlier Texas Art Group “Planned, Organized and Established: Houston Artist Cooperatives of the 1930s,” like all good things (as the saying goes), has come to an end. -

Bruce and Barbara Feldacker Labor Art Collection Reference Collection

Page 1 of 31 Bruce and Barbara Feldacker Labor Art Collection Reference Collection These books may be accessed through the Mercantile Library Rare Book Reading Room. All books are non-circulating. Book # Author Title Publication Info. Notes The Painter's America: Rural and Urban In association with the Whitney 4 Hills, Patricia Life, 1810-1910 [The] New York: Praeger Publishers, 1974 Museum of American Art Selections from the Penny and Elton Yasuna Collection; Essays Jeffett, William, ed. Surrealism in America During the 1930s by Martica Sawin and William 6 (curator) and 1940s FL: Salvador Dali Museum Jeffett With an essay by Guy Davenport; New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., from the Museum of Modern Art, 7 Castleman, Riva (ed.) Art of the Forties 1994 New York Los Angeles: The Wheatley Press, In association with the University 8 DeNoon, Christopher Posters of the WPA 1987 of Washington Press, Seattle Social Concern and Urban Realism: Publication Center Cultural Resources, 9 Hills, Patricia American Painting of the 1930s 1983 With an essay by Raphael Soyer Precisionism in America 1915-1941: New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., In association with the Montclair 11 Murphy, Diana Reordering Reality 1995 Art Museum 13 Kent, Norman (ed.) Drawings by American Artists New York: Bonanza Books, 1970 ASIN: B000G5WO7Q Page 2 of 31 Slatkin, Charles E. and New York: Oxford University Press, 14 Shoolman, Regina Treasury of American Drawings 1947 ASIN: B0006AR778 15 American Art Today National Art Society, 1939 ASIN: B000KNGRSG Eyes on America: The United States as New York: The Studio Publications, Introduction and commentary on 16 Hall, W.S. -

Retrospective Exhibit of Stuart Davis

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ACRTMMEDIATE RELEASE tl WEST 53RD STREET, NEW YORK 19, N. Y. ELEPHONE: MfAggP^ e8& MODERN ART PRESENTS ONE-MAN RETROSPECTIVE EXHIBITION OF PAINTINGS BY STUART DAVIS Stuart Davis is a painter of the American scene. Through his art he translates its spirit and its rhythms into paint. As he expresses it: "I have enjoyed the dynamic American scene for many years, and all my pictures (including the ones I painted in Paris) are referential to it. They all have their originating impulse in the impact of contemporary American environment. Some of the things that have made me want to paint, outside of other paintings are: American wood and iron work1 of the past; Civil War and skyscraper architecture; the brilliant colors on gasoline stations, chain store fronts, and taxicabs; the music of Bach; synthetic chemistry; ... fast travel "by train, auto and aeroplane which has brought new and multiple perspectives; electric signs; the landscape and boats of Gloucester, Massa chusetts; five-and-ten-cent store kitchen utensils; movies and radio; Earl Hines1 hot piano and Negro Jazz music in general, etc." A one-man show of Stuart Davis' work will open at the Museum of Modern Art Wednesday, October 17. It will cover his production from Self-Portrait painted in 1912 when the artist was only eighteen, to paintings of 1945—showing a cross-section of the work which has caused Davis to be regarded as one of the leaders of American art. The exhibition, which will remain'on.view through February 3, 1946, will consist of approximately fifty oil paintings, mural panels, drawings and watercolors.