The Alterity of the Readymade: Fountain and Displaced Artists in Wartime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My New Cover.Pptx

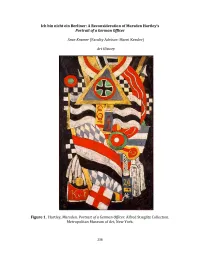

Ich bin nicht ein Berliner: A Reconsideration of Marsden Hartley's Portrait of a German Officer Sean Kramer (FacultyAdvisor: Marni Kessler) Art History Figure I7 8artley9 Marsden7 Portrait of a German Officer. Alfred ;tie<lit= >ollection7 Metro?olitan Museum of Art9 New York. 236 German Officer with a formal analysis of This painting, executed in November 1914, the painting. I then use semiotic theory to shows Hartley's assimilation of both Cubism begin to unpack notions of a singular, (the collagelike juxtapositions of visual fragments) and German Expressionism (the "correct" interpretation of the painting coarse brushwork and dramatic use of bright and to emphasize the multiform nature of colors and black). In 1916 the artist denied that reception. In this section, I seek to the objects in the painting had any special establish that the artist's personal meaning (perhaps as a defensive measure to connection to the artwork is not ward off any attacks provoked by the intense anti-German sentiment in America at the time). necessarily the most important However, his purposeful inclusion of medals, interpretive guideline for working with banners, military insignia, the Iron Cross, and this image. I then use examples of letters the German imperial flag does invoke a specific and numerals within the work to sense of Germany during World War I as well illustrate the plurality of cultural and as a collective psychological and physical linguistic processes which inform portrait of a particular officer.1 viewership of the painting. Meanings in a text, I posit, rely on the interaction between the contexts of the viewer and of This quotation comes from a section the author. -

Marsden Hartley on Cape Ann : Hartley’S 16 Year Relationship with Cape Ann Lecture Transcript

MARSDEN HARTLEY ON CAPE ANN : HARTLEY’S 16 YEAR RELATIONSHIP WITH CAPE ANN LECTURE TRANSCRIPT Speaker: Elyssa East Date: 8/18/2012 Runtime: 0:56:10 Camera Operator: unknown Identification: VL46 ; Video Lecture #46 Citation: East, Elyssa. “Marsden Hartley on Cape Ann : Hartley’s 16 Year Relationship with Cape Ann.” CAM Video Lecture Series, 8/18/2012. VL46, Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, MA. Copyright: Requests for perMission to publish Material from this collection should be addressed to the Librarian/Archivist. Language: English Finding Aid: Video Description: 2012 Press Release Subject List: Trudi Olivetti, 6/24/2020 Transcript: Linda Berard, 4/15/2020. Video Description FroM 2012 Press Release: In 1931, the AMerican Early Modernist painter Marsden Hartley spent a life-altering suMMer in Dogtown. But Hartley had a long-standing relationship with Cape Ann that began years earlier. Elyssa East, author of Dogtown: Death and Enchantment in a New England Ghost Town, will discuss Hartley's sixteen-year relationship with Cape Ann and how it Marsden Hartley on Cape Ann – VL46 – page 2 changed his life and work. “Marsden Hartley on Cape Ann” is offered in conjunction with the special exhibition Marsden Hartley: Soliloquy in Dogtown, which is on display at the Cape Ann MuseuM through October 14. The lecture is generously sponsored by the Cape Ann Savings Bank. Elyssa East is the author of Dogtown: Death and Enchantment in a New England Ghost Town, which won the 2010 P.E.N. New England/L. L. Winship award in Nonfiction. A Boston Globe bestseller, Dogtown was named a “Must-Read Book” by the Massachusetts Book Awards and an Editors’ Choice Selection of the New York TiMes Sunday Book Review. -

Cubism in America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1985 Cubism in America Donald Bartlett Doe Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Part of the Art and Design Commons Doe, Donald Bartlett, "Cubism in America" (1985). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. RESOURCE SERIES CUBISM IN SHELDON MEMORIAL ART GALLERY AMERICA Resource/Reservoir is part of Sheldon's on-going Resource Exhibition Series. Resource/Reservoir explores various aspects of the Gallery's permanent collection. The Resource Series is supported in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. A portion of the Gallery's general operating funds for this fiscal year has been provided through a grant from the Institute of Museum Services, a federal agency that offers general operating support to the nation's museums. Henry Fitch Taylor Cubis t Still Life, c. 19 14, oil on canvas Cubism in America .".. As a style, Cubism constitutes the single effort which began in 1907. Their develop most important revolution in the history of ment of what came to be called Cubism art since the second and third decades of by a hostile critic who took the word from a the 15th century and the beginnings of the skeptical Matisse-can, in very reduced Renaissance. -

The German Century? How a Geopolitical Approach Could Transform the History of Modernism Catherine Dossin, Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel

The German Century? How a Geopolitical Approach Could Transform The History of Modernism Catherine Dossin, Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel To cite this version: Catherine Dossin, Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel. The German Century? How a Geopolitical Approach Could Transform The History of Modernism. Circulations in the Global History of Art, Ashgate / Routledge, 2015, 9781472454560. hal-01479061 HAL Id: hal-01479061 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01479061 Submitted on 12 Feb 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright Warning : this document is proposed at its state before publication. I encourage you to use the version published by Ashgate, which includes definitive maps and graphs, and in a revised version. The German Century: How a Geopolitical Approach Could Transform the History of Modernism Catherine Dossin and Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel Writing a global history of art is one of the highest challenges faced by the specialists of modernism, but not their favorite orientation.1 When writing a global history of modern and contemporary art, the trend seems to be directed towards adding chapters dedicated to non-Western regions.2 Yet, those added chapters do not fundamentally alter the main narrative. -

HARD FACTS and SOFT SPECULATION Thierry De Duve

THE STORY OF FOUNTAIN: HARD FACTS AND SOFT SPECULATION Thierry de Duve ABSTRACT Thierry de Duve’s essay is anchored to the one and perhaps only hard fact that we possess regarding the story of Fountain: its photo in The Blind Man No. 2, triply captioned “Fountain by R. Mutt,” “Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz,” and “THE EXHIBIT REFUSED BY THE INDEPENDENTS,” and the editorial on the facing page, titled “The Richard Mutt Case.” He examines what kind of agency is involved in that triple “by,” and revisits Duchamp’s intentions and motivations when he created the fictitious R. Mutt, manipulated Stieglitz, and set a trap to the Independents. De Duve concludes with an invitation to art historians to abandon the “by” questions (attribution, etc.) and to focus on the “from” questions that arise when Fountain is not seen as a work of art so much as the bearer of the news that the art world has radically changed. KEYWORDS, Readymade, Fountain, Independents, Stieglitz, Sanitary pottery Then the smell of wet glue! Mentally I was not spelling art with a capital A. — Beatrice Wood1 No doubt, Marcel Duchamp’s best known and most controversial readymade is a men’s urinal tipped on its side, signed R. Mutt, dated 1917, and titled Fountain. The 2017 centennial of Fountain brought us a harvest of new books and articles on the famous or infamous urinal. I read most of them in the hope of gleaning enough newly verified facts to curtail my natural tendency to speculate. But newly verified facts are few and far between. -

Archives of American Art Journal, Vol. 49 Nos. 1-2: the Anniversary Issue

From the director This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of theArchives of American Art Journal. What started as a modest pamphlet for announcing new acquisitions and other Archives’ activities soon blossomed into one of the signature publications for the dissemination of new research in the field of American art history. During its history, the Archives has published the work of most of the leading thinkers in the field. The list of contributors is far too long to include, but choose a name and most likely their bibliography will include an essay for the Journal. To celebrate this occasion, we mined the Journal’s archive and reprinted some of the finest and most representative work to have appeared in these pages in the past five decades. Additionally, we invited several leading scholars to prepare short testimonies to the value of the Journal and to the crucial role that the Archives has played in advancing not only their own work, but its larger mission to foster a wider appreciation and deeper understanding of American art and artists. I’m particularly grateful to Neil Harris, Patricia Hills, Gail Levin, Lucy Lippard, and H. Barbara Weinberg for their thoughtful tributes to the Journal. Additionally, I’d like to thank David McCarthy, Gerald Monroe, H. Barbara Weinberg, and Judith Zilczer for their essays. And I would like to make a very special acknowledgement to Garnett McCoy, who served as the Journal’s editor for thirty years. As our current editor Darcy Tell points out, the Journal’s vigor and intellectual rigor owe much to Garnett’s stewardship and keen Endpapers inspired by the Artists' Union logo. -

The Richard Mutt Case'

248 Rationalization and Transformation Dadaism - a mask play, a burst of laughter? And behind it, a synthesis of the romantic, dandyistic and - daemonistic theories of the 19thcentury. 2 Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) 'The Richard Mutt Case' Duchamp, having abandoned painting and emigrated to America, began to produce 'Readymades', works calculated to reveal, among their other effects, the workings of the art institution as inseparable from the attribution of artistic value. In 1917, under the pseudonym Richard Mutt, he submitted a urinal to an open sculpture exhibition; the piece was refused entry (as he no doubt intended). The present text was originally published in The Blind Man, New York, 1917. It is reproduced here from Lucy Lipparcl (ed.), Dadas on Art, New Jersey, 1971. They say any artist paying six dollars may exhibit. Mr Richard Mutt sent ih a 'fountain. Without discussion this article disap peared and never was exhibited. What were the grounds for refusing Mr Mutt's fountain: - 1 Some contended it was immoral, vulgar. 2 Others, it was plagiarism, a plain pkce of plumbing. Now Mr Mutt's fountain is not immoral, that is absurd, no more than a bathtub is immoral. It is a fixture that you see every day in plumbers' show windows. Whether Mr Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view - created a new thought for that object. ' · As for plumbing, that is absurd. -

Genius Is Nothing but an Extravagant Manifestation of the Body. — Arthur Cravan, 1914

1 ........................................... The Baroness and Neurasthenic Art History Genius is nothing but an extravagant manifestation of the body. — Arthur Cravan, 1914 Some people think the women are the cause of [artistic] modernism, whatever that is. — New York Evening Sun, 1917 I hear “New York” has gone mad about “Dada,” and that the most exotic and worthless review is being concocted by Man Ray and Duchamp. What next! This is worse than The Baroness. By the way I like the way the discovery has suddenly been made that she has all along been, unconsciously, a Dadaist. I cannot figure out just what Dadaism is beyond an insane jumble of the four winds, the six senses, and plum pudding. But if the Baroness is to be a keystone for it,—then I think I can possibly know when it is coming and avoid it. — Hart Crane, c. 1920 Paris has had Dada for five years, and we have had Else von Freytag-Loringhoven for quite two years. But great minds think alike and great natural truths force themselves into cognition at vastly separated spots. In Else von Freytag-Loringhoven Paris is mystically united [with] New York. — John Rodker, 1920 My mind is one rebellion. Permit me, oh permit me to rebel! — Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, c. 19251 In a 1921 letter from Man Ray, New York artist, to Tristan Tzara, the Romanian poet who had spearheaded the spread of Dada to Paris, the “shit” of Dada being sent across the sea (“merdelamerdelamerdela . .”) is illustrated by the naked body of German expatriate the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (see fig. -

Information to Users

Alfred Stieglitz and the opponents of Photo-Secessionism Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Zimlich, Leon Edwin, Jr., 1955- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 21:07:09 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/291519 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

The Influence of Gertrude Stein on Marsden Hartley’S Approach to the Object Portrait Genre Christal Hensley

One Portrait of One Woman: The Influence of Gertrude Stein on Marsden Hartley’s Approach to the Object Portrait Genre Christal Hensley Marsden Hartley’s 1916 painting One Portrait of One Woman Hartley’s circle that assembled abstract and/or symbolic forms is an object portrait of the American abstractionist poet and in works called “portraits.”4 writer Gertrude Stein (Figure 1). Object portraits are based on Although several monographs address Stein’s impact on an object or a collage of objects, which through their associa- Hartley’s object portraits, none explores the formal aspects of tion evoke the image of the subject in the title. In this portrait, this relationship.5 This paper first argues that Hartley’s initial the centrally located cup is set upon an abstraction of a checker- approach to the object portrait genre developed independently board table, placed before a half-mandorla of alternating bands of that of other artists in his circle. Secondly, this discussion of yellow and white, and positioned behind the French word posits that Hartley’s debt to Stein was not limited to her liter- moi. Rising from the half-mandorla is a red, white and blue ary word portraits of Picasso and Matisse but extended to her pattern that Gail Scott reads as an abstraction of the Ameri- collection of “portraits” of objects entitled Tender Buttons: can and French flags.1 On the right and left sides of the can- Objects, Food, Rooms, published in book form in 1914. And vas are fragments of candles and four unidentified forms that finally, this paper concludes that Hartley’s One Portrait of echo the shape of the half-mandorla. -

The Artwork Caught by the Tail*

The Artwork Caught by the Tail* GEORGE BAKER If it were married to logic, art would be living in incest, engulfing, swallowing its own tail. —Tristan Tzara, Manifeste Dada 1918 The only word that is not ephemeral is the word death. To death, to death, to death. The only thing that doesn’t die is money, it just leaves on trips. —Francis Picabia, Manifeste Cannibale Dada, 1920 Je m’appelle Dada He is staring at us, smiling, his face emerging like an exclamation point from the gap separating his first from his last name. “Francis Picabia,” he writes, and the letters are blunt and childish, projecting gaudily off the canvas with the stiff pride of an advertisement, or the incontinence of a finger painting. (The shriek of the commodity and the babble of the infant: Dada always heard these sounds as one and the same.) And so here is Picabia. He is staring at us, smiling, a face with- out a body, or rather, a face that has lost its body, a portrait of the artist under the knife. Decimated. Decapitated. But not quite acephalic, to use a Bataillean term: rather the reverse. Here we don’t have the body without a head, but heads without bodies, for there is more than one. Picabia may be the only face that meets our gaze, but there is also Metzinger, at the top and to the right. And there, just below * This essay was written in the fall of 1999 to serve as a catalog essay for the exhibition Worthless (Invaluable): The Concept of Value in Contemporary Art, curated by Carlos Basualdo at the Moderna Galerija Ljubljana, Slovenia. -

Before Zen: the Nothing of American Dada

Before Zen The Nothing of American Dada Jacquelynn Baas One of the challenges confronting our modern era has been how to re- solve the subject-object dichotomy proposed by Descartes and refined by Newton—the belief that reality consists of matter and motion, and that all questions can be answered by means of the scientific method of objective observation and measurement. This egocentric perspective has been cast into doubt by evidence from quantum mechanics that matter and motion are interdependent forms of energy and that the observer is always in an experiential relationship with the observed.1 To understand ourselves as in- terconnected beings who experience time and space rather than being sub- ject to them takes a radical shift of perspective, and artists have been at the leading edge of this exploration. From Marcel Duchamp and Dada to John Cage and Fluxus, to William T. Wiley and his West Coast colleagues, to the recent international explosion of participatory artwork, artists have been trying to get us to change how we see. Nor should it be surprising that in our global era Asian perspectives regarding the nature of reality have been a crucial factor in effecting this shift.2 The 2009 Guggenheim exhibition The Third Mind emphasized the im- portance of Asian philosophical and spiritual texts in the development of American modernism.3 Zen Buddhism especially was of great interest to artists and writers in the United States following World War II. The histo- ries of modernism traced by the exhibition reflected the well-documented influence of Zen, but did not include another, earlier link—that of Daoism and American Dada.