Of Owner Or Discontinuance of His Possession. 2257. in Yeknath Vs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6. Understanding the Epistemology of Talaq

2016 (2) Elen. L R 6. UNDERSTANDING THE EPISTEMOLOGY OF TALAQ UNDER THE SHARIAT LAW Neema Noor Mohamed1 Introduction “Talaq” has turned out to be one of the most debated topic in the recent past in the contemporary India. Indian Muslim women living in the 21st century globalising world had to be the victims of the most arbitrary practice called “Triple Talaq” that legally prevailed in India until the historic judgement delivered by the constitutional Bench of Supreme court through ShayaraBano and others vs Union of India. This is a time to retrospect what made India, the largest democratic country to take such a long time to abolish this unislamic and unconstitutional practice, which has been abolished even by those countries where Shariat is the law of the land. This practice of triple Talaq was totally in contradiction with the law of divorce as held in the Quran. The sad reality is that divorce especially in the form of Talaq (divorce by husband) is the most misinterpreted incident leading to much suffering to the Muslim women. To quote Noel James Coulson, “without doubt it is the institution of Talaq which stands out in the whole range of the family law as occasioning the gravest prejudice to the status of Muslim women” (Quoted in Pearl and Meski 1988: 286). To a vast extend during his lifetime; Prophet Mohammad (PBUH) through his intellectualism and divinity, brought systematisation and Islamicization in every aspect of human conduct and relations. Unfortunately after the death of Prophet, his followers could not take up the legacy with the time and space which led to havoc in various aspects of Islamic Jurisprudence. -

Dictionary of Martyrs: India's Freedom Struggle

DICTIONARY OF MARTYRS INDIA’S FREEDOM STRUGGLE (1857-1947) Vol. 5 Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu & Kerala ii Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) Vol. 5 DICTIONARY OF MARTYRSMARTYRS INDIA’S FREEDOM STRUGGLE (1857-1947) Vol. 5 Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu & Kerala General Editor Arvind P. Jamkhedkar Chairman, ICHR Executive Editor Rajaneesh Kumar Shukla Member Secretary, ICHR Research Consultant Amit Kumar Gupta Research and Editorial Team Ashfaque Ali Md. Naushad Ali Md. Shakeeb Athar Muhammad Niyas A. Published by MINISTRY OF CULTURE, GOVERNMENT OF IDNIA AND INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH iv Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) Vol. 5 MINISTRY OF CULTURE, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA and INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH First Edition 2018 Published by MINISTRY OF CULTURE Government of India and INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH 35, Ferozeshah Road, New Delhi - 110 001 © ICHR & Ministry of Culture, GoI No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN 978-81-938176-1-2 Printed in India by MANAK PUBLICATIONS PVT. LTD B-7, Saraswati Complex, Subhash Chowk, Laxmi Nagar, New Delhi 110092 INDIA Phone: 22453894, 22042529 [email protected] State Co-ordinators and their Researchers Andhra Pradesh & Telangana Karnataka (Co-ordinator) (Co-ordinator) V. Ramakrishna B. Surendra Rao S.K. Aruni Research Assistants Research Assistants V. Ramakrishna Reddy A.B. Vaggar I. Sudarshan Rao Ravindranath B.Venkataiah Tamil Nadu Kerala (Co-ordinator) (Co-ordinator) N. -

VADLAMUDI-THESIS.Pdf (550.0Kb)

Copyright By Sundara Sreenivasa R Vadlamudi 2010 The Thesis Committee for Sundara Sreenivasa R Vadlamudi Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Daud Shah and Socio-religious reform among Muslims in the Madras Presidency APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE Supervisor: ______________________________ Gail Minault _____________________________ Cynthia Talbot Daud Shah and Socio-religious Reform among Muslims in the Madras Presidency by Sundara Sreenivasa R Vadlamudi, M.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2010 Dedication To my family For believing in me and my dreams Acknowledgements This work would not have been accomplished without the support and guidance of several people. Professor Gail Minault was a tremendous source of guidance and encouragement. Her interest and curiosity about Muslims in Tamil Nadu has greatly inspired me. Professor Cynthia Talbot patiently waited, read earlier drafts, and provided extremely useful comments. Marilyn Lehman uncomplainingly answered my questions and tolerated my requests regarding coursework and funding. I would like to thank members of the History Department’s Graduate Program Committee (GPC) for funding my research. I am extremely grateful to Qazi Zainul Abideen for providing me with copies of journals that are used in this thesis. He has become a good friend and I am glad to have met such a wonderful person. I would also like to thank the staff of the Tamil Nadu State Archives for going the extra mile to retrieve dusty records without any complaints. -

Special Issue 5 November 2018 E-ISSN: 2456-5571

BODHI International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Science Vol: 3 Special Issue: 5 November 2018 E-ISSN: 2456-5571 CENTRE FOR RESOURCE, RESEARCH & PUBLICATION SERVICES (CRRPS) www.crrps.in | www.bodhijournals.com BODHI BODHI International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Science (E-ISSN: 2456-5571) is online, peer reviewed, Refereed and Quarterly Journal, which is powered & published by Center for Resource, Research and Publication Services, (CRRPS) India. It is committed to bring together academicians, research scholars and students from all over the world who work professionally to upgrade status of academic career and society by their ideas and aims to promote interdisciplinary studies in the fields of humanities, arts and science. The journal welcomes publications of quality papers on research in humanities, arts, science. agriculture, anthropology, education, geography, advertising, botany, business studies, chemistry, commerce, computer science, communication studies, criminology, cross cultural studies, demography, development studies, geography, library science, methodology, management studies, earth sciences, economics, bioscience, entrepreneurship, fisheries, history, information science & technology, law, life sciences, logistics and performing arts (music, theatre & dance), religious studies, visual arts, women studies, physics, fine art, microbiology, physical education, public administration, philosophy, political sciences, psychology, population studies, social science, sociology, social welfare, linguistics, literature and so on. Research should be at the core and must be instrumental in generating a major interface with the academic world. It must provide a new theoretical frame work that enable reassessment and refinement of current practices and thinking. This may result in a fundamental discovery and an extension of the knowledge acquired. Research is meant to establish or confirm facts, reaffirm the results of previous works, solve new or existing problems, support theorems; or develop new theorems. -

Pembagian Waris Pada Komunitas Tamil Muslim Di Kota Medan

PEMBAGIAN WARIS PADA KOMUNITAS TAMIL MUSLIM DI KOTA MEDAN TESIS Oleh MUMTAZHA AMIN 147011016/M.Kn FAKULTAS HUKUM UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2016 Universitas Sumatera Utara PEMBAGIAN WARIS PADA KOMUNITAS TAMIL MUSLIM DI KOTA MEDAN TESIS Diajukan Untuk Memperoleh Gelar Magister Kenotariatan Pada Program Studi Magister Kenotariatan Fakultas Hukum Universitas Sumatera Utara Oleh MUMTAZHA AMIN 147011016/M.Kn FAKULTAS HUKUM UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2016 Universitas Sumatera Utara Judul Tesis : PEMBAGIAN WARIS PADA KOMUNITAS TAMIL MUSLIM DI KOTA MEDAN Nama Mahasiswa : MUMTAZHA AMIN NomorPokok : 147011016 Program Studi : Kenotariatan Menyetujui Komisi Pembimbing (Dr. Edy Ikhsan, SH, MA) Pembimbing Pembimbing (Dr. T. Keizerina Devi A, SH, CN, MHum) (Dr.Utary Maharany Barus, SH, MHum) Ketua Program Studi, Dekan, (Prof.Dr.Muhammad Yamin,SH,MS,CN) (Prof.Dr.Budiman Ginting,SH,MHum) Tanggal lulus : 16 Juni 2016 Universitas Sumatera Utara Telah diuji pada Tanggal : 16 Juni 2016 PANITIA PENGUJI TESIS Ketua : Dr. Edy Ikhsan, SH, MA Anggota : 1. Dr. T. Keizerina Devi A, SH, CN, MHum 2. Dr. Utary Maharany Barus, SH, MHum 3. Prof. Dr. Muhammad Yamin, SH, MS, CN 4. Dr. Rosnidar Sembiring, SH, MHum Universitas Sumatera Utara SURAT PERNYATAAN Saya yang bertanda tangan dibawah ini : Nama : MUMTAZHA AMIN Nim : 147011016 Program Studi : Magister Kenotariatan FH USU Judul Tesis : PEMBAGIAN WARIS PADA KOMUNITAS TAMIL MUSLIM DI KOTA MEDAN Dengan ini menyatakan bahwa Tesis yang saya buat adalah asli karya saya sendiri bukan Plagiat, apabila dikemudian hari diketahui Tesis saya tersebut Plagiat karena kesalahan saya sendiri, maka saya bersedia diberi sanksi apapun oleh Program Studi Magister Kenotariatan FH USU dan saya tidak akan menuntut pihak manapun atas perbuatan saya tersebut. -

The Political Construction of Caste in South India

The Political Construction of Caste in South India Vijayendra Rao ([email protected]) Development Research Group, The World Bank And Radu Ban ([email protected]) London School of Economics and Development Research Group, The World Bank August 2007 We thank seminar participants at the World Bank’s research department and Karla Hoff for helpful conversations and comments. Jillian Waid and Babu Srinivas Dasari provided excellent research assistance. This paper reflects the views of the authors and should not be attributed to the World Bank, its member countries or any affiliated organization. We are indebted to the Dutch government, and the Research Support Budget of the Development Economics Vice-Presidency of the World Bank, for financial support. Abstract Are social institutions endogenous? Can measures of social diversity (e.g. fractionalization) be treated as exogenous variables in assessing their impact on economic and political outcomes? The caste system, which categorizes Hindus into endogamous and stratified social groups, is considered to be the organizing institution of Indian society. It is widely thought to have stayed stable for hundreds if not thousands of years -- so deeply resistant to change that it has been blamed for everything from (formerly) anemic “Hindu” rates of growth, to persistent “inequality traps.” This paper uses a natural experiment -- the 1956 reorganization of Indian states along linguistic lines – to demonstrate that the number and nomenclature of castes has significantly changed in linguistically matched villages (i.e. “mistakes” in the reorganization) at the borders of these states. This shows that the caste system is not stable but a pliable institution - endogenous to political change. -

Print Culture Amongst Tamils and Tamil Muslims in Southeast Asia, C.1860-1960

Working Paper No. 167 Print Culture amongst Tamils and Tamil Muslims in Southeast Asia, c.1860-1960 by Dr. S.M.A.K. Fakhri Madras Institute of Development Studies 79, Second Main Road, Gandhi Nagar Adyar, Chennai 600 020 February 2002 Print Culture amongst Tamils and Tamil Muslims in Southeast Asia, c. 1860-1960 Authors name and institutional affiliation: Dr SM AK Fakhri Affiliate, June-December 2001 Madras Institute of Development Studies. Abstract of paper: This paper is about the significance of print in the history of Tamil migration to Southeast Asia. During the age of Empire people migrated from India to colonial Malaya resulting in the creation of newer cultural and social groups in their destination (s). What this .meant in a post-colonial context is that while they are citizens of a country they share languages of culture, religion and politics with 'ethnic kin' in other countries. Tamils and Tamil-speaking Muslims from India were one such highly mobile group. They could truly be called 'Bay of Bengal transnational communities' dispersed in Myanmar, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam. The construction of post-colonial national boundaries constricted but did not affect the transnationalism of Tamils across geographies and nation-states. A thriving and successful print culture is a pointer to the manner in which Tamils and Tamil Muslim expressed their transnational (Tamil) identities. Such a print culture this paper suggests is a rich and valuable source of social history. Keywords Print, Print Culture, transnational communities, migration, mobility, social history, Tamils, Tamil Muslims, India, Indian migrants, Indian Ocean region. Acknowledgements This paper was presented at the Conference on 'Southeast Asian Historiography since 1945' July 30 to August I, 1999 by the History Section, School of Humanities, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia as 'Cues for Historiography?•: Print Culture, Print Leaders and Print Mobility among Tamil Muslims in Southeast Asia, c. -

Legal Change and Gender Inequality: Changes in Muslim Family Law In

Law & Social Inquiry Volume 33, Issue 3, 631–672, Summer 2008 LegalBlackwellOxford,LSILaw0897-65461747-4469©XXXOriginalLAW 2008 & Change& Social AmericanUKSOCIALArticles Publishing andInquiry Gender INQUIRYBar Ltd Foundation. Inequality Change and Gender Inequality: Changes in Muslim Family Law in India Narendra Subramanian Group-specific family laws are said to provide women fewer rights and impede policy change. India’s family law systems specific to religious groups underwent important gender-equalizing changes over the last generation. The changes in the laws of the religious minorities were unexpected, as conservative elites had considerable indirect influence over these laws. Policy elites changed minority law only if they found credible justification for change in group laws, group norms, and group initiatives, not only in constitutional rights and transnational human rights law. Muslim alimony and divorce laws were changed on this basis, giving women more rights without abandoning cultural accommodation. Legal mobilization and the outlook of policy makers—specifically their approach to regulating family life, their understanding of group norms, and their normative vision of family life—shaped the major changes in Indian Muslim law. More gender- equalizing legal changes are possible based on the same sources. Narendra Subramanian is an associate professor of political science at McGill University; he can be reached at [email protected]. The author wishes to thank Josh Cohen, Lawrence Cohen, David Gilmartin, Akhil Gupta, Wael Hallaq, Donald Horowitz, Nazia Yusuf Izuddin, Werner Menski, K. Sivaramakrishnan, Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Sylvia Vatuk, and four anonymous referees for their comments on earlier drafts; and Ashok Kotwal, Tuli Banerjee, K. Sivaramakrishnan, Akhil Gupta, and Tambirajah Ponnuthurai for providing opportunities to present the article. -

(C) No. 118 of 2016 Shayara Bano … Petitioner Versus Union of India and Others … Respondents

Reportable IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Original Civil Jurisdiction Writ Petition (C) No. 118 of 2016 Shayara Bano … Petitioner versus Union of India and others … Respondents with Suo Motu Writ (C) No. 2 of 2015 In Re: Muslim Women’s Quest For Equality versus Jamiat Ulma-I-Hind Writ Petition(C) No. 288 of 2016 Aafreen Rehman … Petitioner versus Union of India and others … Respondents Writ Petition(C) No. 327 of 2016 Gulshan Parveen … Petitioner versus Union of India and others … Respondents Writ Petition(C) No. 665 of 2016 Ishrat Jahan … Petitioner versus Union of India and others … Respondents Writ Petition(C) No. 43 of 2017 Atiya Sabri … Petitioner versus Union of India and others … Respondents J U D G M E N T Jagdish Singh Khehar, CJI. 2 Index Sl. Divisions Contents Para-grap No. hs 1. Part-1 The petitioner’s marital discord, and the 1- 10 petitioner’s prayers 2. Part-2 The practiced modes of ‘talaq’ amongst 11- 16 Muslims 3. Part-3 The Holy Quran – with reference to ‘talaq’ 17- 21 4. Part-4 Legislation in India, in the field of Muslim 22- 27 ‘personal law’ 5. Part-5 Abrogation of the practice of ‘talaq-e-biddat’ by 28- 29 legislation, the world over, in Islamic, as well as, non-Islamic States A. Laws of Arab States (i) – (xiii) B. Laws of Southeast Asian States (i) – (iii) C. Laws of Sub-continental States (i) – (ii) 6. Part-6 Judicial pronouncements, on the subject of 30 - 34 ‘talaq-e-biddat’ 7. Part-7 The petitioner’s and the interveners’ 35 – 78 contentions: 8. -

Supreme Court of India Judgment WP(C)

Reportable IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Original Civil Jurisdiction Writ Petition (C) No. 118 of 2016 Shayara Bano … Petitioner versus Union of India and others … Respondents with Suo Motu Writ (C) No. 2 of 2015 In Re: Muslim Women’s Quest For Equality versus Jamiat Ulma-I-Hind Writ Petition(C) No. 288 of 2016 Aafreen Rehman … Petitioner versus Union of India and others … Respondents Writ Petition(C) No. 327 of 2016 Gulshan Parveen … Petitioner versus Union of India and others … Respondents Writ Petition(C) No. 665 of 2016 Ishrat Jahan … Petitioner versus Union of India and others … Respondents Writ Petition(C) No. 43 of 2017 Atiya Sabri … Petitioner versus Union of India and others … Respondents J U D G M E N T Jagdish Singh Khehar, CJI. Index Sl. Divisions Contents Para - No. graphs 1. Part -1 The petitioner’s marital discord, and the 1- 10 petitioner’s prayers 2. Part -2 The practiced modes of ‘talaq’ amongst 11 - 16 Muslims 3. Part -3 The Holy Quran – with reference to ‘talaq’ 17 - 21 4. Part -4 Legislation in India, in the field of Muslim 22 - 27 ‘personal law’ 5. Part -5 Abrogation of the practice of ‘talaq -e-biddat’ by 28 - 29 legislation, the world over, in Islamic, as well as, non-Islamic States A. Laws of Arab States (i) – (xiii) B. Laws of Southeast Asian States (i) – (iii) C. Laws of Sub -continental States (i) – (ii) 6. Part -6 Judicial pronouncements, on the subject of 30 - 34 ‘talaq-e-biddat’ 7. Part -7 The petitioner’s and the interven ers’ 35 – 78 contentions: 8. -

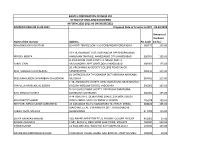

DIVIDEND PAID on 15.04.2021 Name of the Investor

RAILTEL CORPORATION OF INDIA LTD DETAILS OF UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND INTERIM 2020-2021 AS ON 30/06/2021 DIVIDEND PAID ON 15.04.2021 Proposed Date of Transfer to IEPF : 28.04.2028 Amount of Dividend Name of the Investor Address Pin Code (In Rs.) MR MANSUKH M DATTANI B/H KIRTI TEMPLE SONI VAD PORBANDAR PORBANDAR 360575 155.00 10-118, NAVRANG FLAT, BAPUNAGAR OPP BHIDBHANJAN MR DEV MEHTA HANUMAN TAMPALE, AHMEDABAD CITY AHMEDABAD 380024 155.00 B-1/64,ARJUN TOWER OPP.C.P.NAGAR PART-2 SAROJ JOSHI NR.SAUNDRYA APPT.GHATLODIA AHMEDABAD 380061 155.00 20, KRUSHNAKUNJ SOCIETY COLLEGE ROAD,TALOD MRS. SONALBEN B BHALAVAT SABARKANTHA 383215 155.00 61 CHITRODIPURA TA VISNAGAR DIST MEHSANA MEHSANA MISS RAMILABEN ISHWARBHAI CHAUDHARI MEHSANA 384001 155.00 C 38, ANANDVAN SOCIETY, NEW SAMA ROAD, NEAR NAVYUG PRAFULLA HARSUKHLAL SODHA ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL VADODARA 390002 192.00 B-201 GOKULDHAM SOCIETY DEDIYASAN MAHESANA RAVI PRAKASH GUPTA MAHESANA MAHESANA 384001 155.00 A 44 HIM STATE DEWA ROAD SHAHEED BHAGAT SINGH MR MUAZZIZ SHARAF WARD AMRAI GAON LUCKNOW LUCKNOW 226028 155.00 MR PATEL NIRAVKUMAR SURESHBHAI 19 DAMODAR FALIYU VARADHARA TA VIRPUR KHEDA 388260 155.00 WARD NO 1, TAL .SHRIRAMPUR DIST. AHMEDNAGAR SARIKA AMOL MAHALE SHRIRAMPUR 413709 155.00 SATYA NARAYAN MANTRI 203, ANAND APPARTMENT, 9, BIJASAN COLONY INDORE 452001 15.00 ROSHNI AGARWAL P 887, BLOCK A, 2ND FLOOR LAKE TOWN KOLKATA 700089 310.00 VINOD KUMAR 11 RAJA ENCLAVE, ROAD NO. 44 PITAMPURA DELHI 110034 155.00 NAYAN MAHENDRABHAI BHOJAK S RAJAWADI CHAWL JAMBLI GALI BORIVALI WEST MUMBAI 400092 10.00 VETTOM HOUSE PANACHEPPALLY P O KOOVAPPALLY (VIA) TOM JOSE VETTOM KOTTAYAM DIST 686518 100.00 FLAT NO-108,ADHITYA TOWERS BALAJI COLONY TIRUPATI T.V.RAJA GOPALAN CHITTOOR(A.P) 517502 100.00 R K ESTET, VIMA NAGAR, RAIYA ROAD, NEAR DR. -

The Impact of Being Tamil on Religious Life Among Tamil Muslims in Singapore Torsten Tschacher a Thesis Submitted for the Degree

THE IMPACT OF BEING TAMIL ON RELIGIOUS LIFE AMONG TAMIL MUSLIMS IN SINGAPORE TORSTEN TSCHACHER (M.A, UNIVERSITY OF COLOGNE, GERMANY) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2006 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is difficult to enumerate all the individuals and institutions in Singapore, India, and Europe that helped me conduct my research and provided me with information and hospitality. Respondents were enthusiastic and helpful, and I have accumulated many debts in the course of my research. In Singapore, the greatest thanks have to go to all the Tamil Muslims, too numerous to enumerate in detail, who shared their views, opinions and knowledge about Singaporean Tamil Muslim society with me in interviews and conversations. I am also indebted to the members of many Indian Muslim associations who allowed me to observe and study their activities and kept me updated about recent developments. In this regard, special mention has to be made of Mohamed Nasim and K. Sulaiman (Malabar Muslim Juma-ath); A.G. Mohamed Mustapha (Rifayee Thareeq Association of Singapore); Naseer Ghani, A.R. Mashuthoo, M.A. Malike, Raja Mohamed Maiden, Moulana Moulavi M. Mohamed Mohideen Faizi, and Jalaludin Peer Mohamed (Singapore Kadayanallur Muslim League); K.O. Shaik Alaudeen, A.S. Sayed Majunoon, and Mohamed Jaafar (Singapore Tenkasi Muslim Welfare Society); Ebrahim Marican (South Indian Jamiathul Ulama and Tamil Muslim Jama‘at); M. Feroz Khan (Thiruvithancode Muslim Union); K.M. Deen (Thopputhurai Muslim Association (Singapore)); Pakir Maideen and Mohd Kamal (Thuckalay Muslim Association); and Farihullah s/o Abdul Wahab Safiullah (United Indian Muslim Association).