Heart Transplantation: a History Lesson of Lazarus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Immunosuppressive Effects in Infection

I Volume 63 January 1970 I1I J- 6 JAN'7O Section of Clinical ~~~~~~~~~ Immunology & Allergy President Professor Sir Michael Woodruff FRCS FRS Meeting April 14 1969 Immunosuppressive Effects in Infection Dr M H Salaman Measles: In 1908 von Pirquet noticed that the (Department ofPathology, Royal College tuberculin reaction in tuberculous children be- ofSurgeons oJ England, came negative during an attack of measles, and London) that afterwards tuberculosis often advanced rapidly. Later work has confirmed his observa- Immunodepression by tions on tuberculin sensitivity by more sensitive Mammalian Viruses and Plasmodia methods (Mellman & Wetton 1963, Brody & McAlister 1964, Starr & Berkovitch 1964), and it Depression of immune responses by viruses is has been shown (Smithwick & Berkovitch 1966) receiving increasing though much belated atten- that measles virus, added to lymphocytes of tion. Early reports (von Pirquet 1908, Bloomfield tuberculin-positive patients, prevents the mito- & Mateer 1919) were forgotten and the subject genic response to tuberculin PPD, but not the neglected till 1960 when Old and his colleagues response to phytohmmagglutinin (PHA). noticed that the hmemolysin response to sheep erythrocytes (SE) was depressed in mice infected Rubella: In infants with congenital rubella there with Friend's leukeemogenic virus (FV), and is no gross defect of antibody formation, but their Gledhill (1961) found that FV and Moloney virus lymphocytes do not respond to PHA (Alford both enhanced the pathogenicity of mouse 1965, Bellanti et al. 1965, Soothill et al. 1966). hepatitis virus. Since then reports of immuno- Normal lymphocytes treated with rubella virus in depression by a wide variety of viruses, both vitro lose their PHA-responsiveness. -

書 名 等 発行年 出版社 受賞年 備考 N1 Ueber Das Zustandekommen Der

書 名 等 発行年 出版社 受賞年 備考 Ueber das Zustandekommen der Diphtherie-immunitat und der Tetanus-Immunitat bei thieren / Emil Adolf N1 1890 Georg thieme 1901 von Behring N2 Diphtherie und tetanus immunitaet / Emil Adolf von Behring und Kitasato 19-- [Akitomo Matsuki] 1901 Malarial fever its cause, prevention and treatment containing full details for the use of travellers, University press of N3 1902 1902 sportsmen, soldiers, and residents in malarious places / by Ronald Ross liverpool Ueber die Anwendung von concentrirten chemischen Lichtstrahlen in der Medicin / von Prof. Dr. Niels N4 1899 F.C.W.Vogel 1903 Ryberg Finsen Mit 4 Abbildungen und 2 Tafeln Twenty-five years of objective study of the higher nervous activity (behaviour) of animals / Ivan N5 Petrovitch Pavlov ; translated and edited by W. Horsley Gantt ; with the collaboration of G. Volborth ; and c1928 International Publishing 1904 an introduction by Walter B. Cannon Conditioned reflexes : an investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex / by Ivan Oxford University N6 1927 1904 Petrovitch Pavlov ; translated and edited by G.V. Anrep Press N7 Die Ätiologie und die Bekämpfung der Tuberkulose / Robert Koch ; eingeleitet von M. Kirchner 1912 J.A.Barth 1905 N8 Neue Darstellung vom histologischen Bau des Centralnervensystems / von Santiago Ramón y Cajal 1893 Veit 1906 Traité des fiévres palustres : avec la description des microbes du paludisme / par Charles Louis Alphonse N9 1884 Octave Doin 1907 Laveran N10 Embryologie des Scorpions / von Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov 1870 Wilhelm Engelmann 1908 Immunität bei Infektionskrankheiten / Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov ; einzig autorisierte übersetzung von Julius N11 1902 Gustav Fischer 1908 Meyer Die experimentelle Chemotherapie der Spirillosen : Syphilis, Rückfallfieber, Hühnerspirillose, Frambösie / N12 1910 J.Springer 1908 von Paul Ehrlich und S. -

History of Lung Transplantation Akciğer Transplantasyonu Tarihçesi

REVIEW History of Lung Transplantation Akciğer Transplantasyonu Tarihçesi Gül Dabak Unit of Pulmonology, Kartal Kosuyolu Yüksek Ihtisas Teaching Hospital for Cardiovascular Diseases and Surgery, İstanbul ABSTRACT ÖZET History of lung transplantation in the world dates back to the early 20 Dünyada akciğer transplantasyonu tarihçesi, deneysel çalışmala- th century, continues to the first clinical transplantation performed rın yapılmaya başlandığı 20. yüzyılın ilk yıllarından itibaren Ja- by James Hardy in the United States of America in 1963 and comes mes Hardy’ nin Amerika Birleşik Devletleri’nde 1963’te yaptığı to the present with increased frequency. Over 40.000 heart-lung ilk klinik transplantasyona uzanır ve hızlanarak günümüze gelir. and lung transplantations were carried out in the world up to 2011 yılına kadar dünyada 40,000’in üzerinde kalp-akciğer ve 2011. The number of transplant centers and patients is flourishing akciğer transplantasyonu yapılmıştır. Transplantasyon alanındaki in accordance with the increasing demand and success rate in that artan ihtiyaca ve başarılara paralel olarak transplant merkezleri arena. Lung transplantations that started in Turkey at Sureyyapasa ve hasta sayıları da giderek artmaktadır. Türkiye’de 2009 yılında Teaching Hospital for Pulmonary Diseases and Thoracic Surgery Süreyyapaşa Göğüs Hastalıkları ve Cerrahisi Eğitim ve Araştırma in 2009 are being performed at two centers actively to date. This Hastanesi’ nde başlayan akciğer transplantasyonları günümüzde review covers a general outlook on lung transplantations both in iki merkezde aktif olarak yapılmaktadır. Bu derlemede, ülkemiz- the world and in Turkey with details of the first successful lung deki ilk başarılı akciğer transplantasyonu detaylandırılarak dün- transplantation in our country. yada ve ülkemizdeki akciğer transplantasyonu tarihçesi gözden Keywords: Lung transplantation, heart-lung transplantation, his- geçirilmektedir. -

The History of the First Kidney Transplantation

165+3 14 mm "Service to society is the rent we pay for living on this planet" The History of the Joseph E. Murray, 1990 Nobel-laureate who performed the first long-term functioning kidney transplantation in the world First Kidney "The pioneers sacrificed their scientific life to convince the medical society that this will become sooner or later a successful procedure… – …it is a feeling – now I am Transplantation going to overdo - like taking part in creation...” András Németh, who performed the first – a European Overview Hungarian renal transplantation in 1962 E d i t e d b y : "Professor Langer contributes an outstanding “service” to the field by a detailed Robert Langer recording of the history of kidney transplantation as developed throughout Europe. The authoritative information is assembled country by country by a generation of transplant professionals who knew the work of their pioneer predecessors. The accounting as compiled by Professor Langer becomes an essential and exceptional reference document that conveys the “service to society” that kidney transplantation has provided for all mankind and that Dr. Murray urged be done.” Francis L. Delmonico, M.D. Professor of Surgery, Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital Past President The Transplantation Society and the Organ Procurement Transplant Network (UNOS) Chair, WHO Task Force Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation The History of the First Kidney Transplantation – a European Overview European a – Transplantation Kidney First the of History The ISBN 978-963-331-476-0 Robert Langer 9 789633 314760 The History of the First Kidney Transplantation – a European Overview Edited by: Robert Langer SemmelweisPublishers www.semmelweiskiado.hu Budapest, 2019 © Semmelweis Press and Multimedia Studio Budapest, 2019 eISBN 978-963-331-473-9 All rights reserved. -

Congenital Heart Disease

GUEST EDITORIAL Congenital heart disease Pediatric Anesthesia is the only anesthesia journal ded- who developed hypoglycemia were infants. (9). Steven icated exclusively to perioperative issues in children and Nicolson take the opposite approach of ‘first do undergoing procedures under anesthesia and sedation. no harm’ (10). If we do not want ‘tight glycemic con- It is a privilege to be the guest editor of this special trol’ because of concern about hypoglycemic brain issue dedicated to the care of children with heart dis- injury, when should we start treating blood sugars? ease. The target audience is anesthetists who care for There are no clear answers based on neurological out- children with heart disease both during cardiac and comes in children. non-cardiac procedures. The latter takes on increasing Williams and Cohen (11) discuss the care of low importance as children with heart disease undergoing birth weight (LBW) infants and their outcomes. Pre- non-cardiac procedures appear to be at a higher risk maturity and LBW are independent risk factors for for cardiac arrest under anesthesia than those without adverse outcomes after cardiac surgery. Do the anes- heart disease (1). We hope the articles in this special thetics we use add to this insult? If prolonged exposure issue will provide guidelines for management and to volatile anesthetics is bad for the developing neona- spark discussions leading to the production of new tal brain, would avoiding them make for improved guidelines. outcomes? Wise-Faberowski and Loepke (12) review Over a decade ago Austin et al. (2) demonstrated the current research in search of a clear answer and the benefits of neurological monitoring during heart conclude that there isn’t one. -

Downloaded and Ready for Use As Soon As the Grade 8S Received - VHS Video on Landforms Their Shiny New Laptops

THE HILTONIAN EDITION 154 APRIL 2019 Contents Board of Governors, Staff and Salvete 2018 4 The Hilton Year 19 Academic Affairs 58 Sport 107 Old Hiltonian News 177 1 2 12 Foreword Within every great institution, the compilation of each year’s On the sporting front, our boys did remarkably. Most history is integral to its grand story. It’s a privilege for me to importantly, all are engaged and learning, whether they're be a part of this particular grand story. 2018 turned out to be playing for the As or the Ds. Our 1st XV had a tremendous a superb year for Hilton College. unbeaten season worthy of celebration. We've also made great strides in our basketball and soccer offerings, which all Our bold vision is to deliver on A Plan for Every Hilton Boy. our boys enjoy. This brave strategy aims to ensure that each boy is understood and then challenged appropriately to work The various reports in this edition of the Hiltonian serve as a towards developing his best version of himself. While we record of events and achievements, but I also hope they continuously work on refining this strategy, we're proud of the convey some of the spirit of this great school which continues fact that each Hilton boy can feel that he has some autonomy to mould boys into young men, ready to take on the world. in his choices and in achieving his personal dreams. Hilton College, founded to raise gentlemen and simultaneously Academically, we embraced a new approach to teaching our serve as a beacon of hope to its surrounding community, is grade 8s and 9s, redesigning the curriculum with an intentional achieving its aims. -

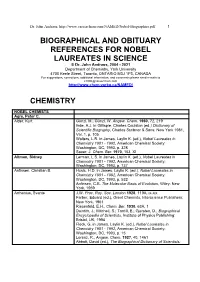

Biographical References for Nobel Laureates

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Nobel-Biographies.pdf 1 BIOGRAPHICAL AND OBITUARY REFERENCES FOR NOBEL LAUREATES IN SCIENCE © Dr. John Andraos, 2004 - 2021 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ CHEMISTRY NOBEL CHEMISTS Agre, Peter C. Alder, Kurt Günzl, M.; Günzl, W. Angew. Chem. 1960, 72, 219 Ihde, A.J. in Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.) Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Charles Scribner & Sons: New York 1981, Vol. 1, p. 105 Walters, L.R. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 328 Sauer, J. Chem. Ber. 1970, 103, XI Altman, Sidney Lerman, L.S. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 737 Anfinsen, Christian B. Husic, H.D. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 532 Anfinsen, C.B. The Molecular Basis of Evolution, Wiley: New York, 1959 Arrhenius, Svante J.W. Proc. Roy. Soc. London 1928, 119A, ix-xix Farber, Eduard (ed.), Great Chemists, Interscience Publishers: New York, 1961 Riesenfeld, E.H., Chem. Ber. 1930, 63A, 1 Daintith, J.; Mitchell, S.; Tootill, E.; Gjersten, D., Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists, Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1994 Fleck, G. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 15 Lorenz, R., Angew. -

2014 FP 1-78:4-Color Section

FINAL PROGRAM 34th Annual Meeting and Scientific Sessions April 10 – 13, 2014 MANCHESTER GRAND HYATT SAN DIEGO International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Gilead is committed to expanding healthcare options for individuals living with cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases through innovative research, access, and education programs. © 2013 Gilead Sciences, Inc. All rights reserved. UNBP0009 March 2013 Gilead and the Gilead logo are trademarks of Gilead Sciences, Inc. INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR HEART AND LUNG TRANSPLANTATION 34th ANNUAL MEETING and SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS April 10 – 13, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS About ISHLT 2 Board of Directors 4 Scientific Program Committee 6 Abstract Reviewers 8 Committees 17 Scientific Councils 25 Past Presidents 32 Daily Schedule Foldouts between 34-47 Award Recipients 35 Continuing Medical Education 46 Annual Meeting 49 Scientific Session Highlights Manchester Grand Hyatt Floor Plans 64 Annual Meeting 67 Schedule At a Glance Corporate Partners 78 Annual Meeting 79 Scientific Program and Schedule Exhibit Hall Floor Plan 278 List of Exhibitors 280 1 2 THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR HEART AND LUNG TRANSPLANTATION (ISHLT) is a not-for-profit, multidisciplinary, professional organization dedicated to improving the care of patients with advanced heart or lung disease through transplantation, mechanical support and innovative therapies via research, educa- tion and advocacy. ISHLT was created in 1981 at a small gathering of The about 15 cardiologists and Purposes cardiac surgeons. Today we of the have over 2700 members from over 45 countries, rep- Society resenting over 15 different are: professional disciplines in- 1. To associate persons volved in the management interested in the fields of heart and treatment of end-stage and lung transplantation, end- heart and lung disease. -

St Catharine's College Society Magazine 1

CONTENTS Sir Terence English 1 Honours and Awards 2 Editorial 3 The Master Elect, Professor David Ingram; University Appointments 4 Governing Body 5 Cheering up Depressed Mussels. Dr David Aldridge 8 Publications 9 Reviews and Notes 10 The College Staff 15 Dr Robert Evans' 90th Birthday Celebration; St Catharine's Gild 16 St Catharine of Alexandria 17 Arctic Circle Ski Race. Hugh Pritchard 18 College Society Reports 21 The St Catharine's Society: The President Elect and Officers of the Society 25 The St Catharine's Society: The AGM 1999 26 The St Catharine's Society: Mr Tom Cook (Honorary Secretary Retired): Presentation 27 The St Catharine's Society: The AGM 2000 Agenda and Sports Fund 28 The St Catharine's Society: Accounts 29 Weddings Births and Deaths 30 Obituaries 37 Matriculations 1999-2000 40 Postgraduates Registered and PhDs Approved 1999-2000 42 Appointments and Notes 44 M.C.R. and J.C.R 48 The Matterhorn Disaster. A. J. Longford 49 Kittens, Cardinals, and Alley cats. Professor Donald Broom 51 Gifts and Bequests; American & Canadian Friends 52 The College Chapel and Choir 53 The Singing Cats. Paul Griffin 54 The St Catharine's Society: Branch News 55 Down to the Sea in Ships. Captain Charles Styles R.N 56 College Club Reports 58 The University Cross Channel Race 2000 64 Blues 1999-2000 65 An Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race 1950 66 Awards and Prizes 68 Dr Paul Raithby and Chemists 72 Honorary Fellowships: Mr Jeremy Paxman and Professor Jonathan Bate 73 The Editor's Desk 74 Development Campaign 76 Annual Dinners: The Society; The Governing Body Invitation 80 Important Notes and Dates for All Readers 81 Cover: As we step into the new millennium College Main Court on Saturday 17th June 2000. -

160528 Dr. Edgar Franke

Prof. Dr. J. Floege • Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hochschule Aachen Universitätsklinikum • Medizinische Klinik II • Pauwelsstr. 30 • 52074 Aachen Geschäftsstelle Seumestr. 8 10245 Berlin Dr. Edgar Franke Ausschuss für Gesundheit Telefon: 030 52137269 Deutscher Bundestag Telefax: 030 52137270 Platz der Republik 1 E-Mail: [email protected] 11011 Berlin www.dgfn.eu Berlin, 29.5.2016 Vorstand: Prof. Dr. J. Floege (Präsident) Rheinisch-Westfälische Sehr geehrter Herr Dr. Franke, Technische Hochschule Aachen Universitätsklinikum Medizinische Klinik II, die Dt. Gesellschaft für Nephrologie bedankt sich für die Gelegenheit Nephrologie und Klinische einer Stellungnahme zum geplanten Transplantationsregister. Immunologie Pauwelsstr. 30 Wir begrüßen die Initiative eines bundesweiten Transplantationsregisters 52074 Aachen ausdrücklich, möchten aber unter Bezugnahme auf das mit Frau Prof. Dr. Elke Telefon: 0241 8089530 Schäffner am 15.4.16 geführte Obleutegespräch an dieser Stelle erneut auf Telefax: 0241 8082446 E-Mail: [email protected] einen Umstand hinweisen, der unserer Ansicht nach in dem bisherigen Gesetzesentwurf zu kurz greift, die Verknüpfung eines Prof. Dr. K. Amann Transplantationsregisters mit einem Dialyseregister. Prof. Dr. M. D. Alscher Prof. Dr. A. Kribben Aus folgenden Gründen halten wir eine solche Datenverknüpfung für Dr. T. Weinreich unerlässlich: Kuratorium: • Die Nephrologie ist in der Transplantationslandschaft einzigartig, da es Prof. Dr. A. Kribben flächendeckend und jahre/jahrzehntelang Nierenersatzverfahren gibt, die (Vorsitzender) -

Balcomk41251.Pdf (558.9Kb)

Copyright by Karen Suzanne Balcom 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Karen Suzanne Balcom Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Discovery and Information Use Patterns of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine Committee: E. Glynn Harmon, Supervisor Julie Hallmark Billie Grace Herring James D. Legler Brooke E. Sheldon Discovery and Information Use Patterns of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine by Karen Suzanne Balcom, B.A., M.L.S. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August, 2005 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my first teachers: my father, George Sheldon Balcom, who passed away before this task was begun, and to my mother, Marian Dyer Balcom, who passed away before it was completed. I also dedicate it to my dissertation committee members: Drs. Billie Grace Herring, Brooke Sheldon, Julie Hallmark and to my supervisor, Dr. Glynn Harmon. They were all teachers, mentors, and friends who lifted me up when I was down. Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my committee: Julie Hallmark, Billie Grace Herring, Jim Legler, M.D., Brooke E. Sheldon, and Glynn Harmon for their encouragement, patience and support during the nine years that this investigation was a work in progress. I could not have had a better committee. They are my enduring friends and I hope I prove worthy of the faith they have always showed in me. I am grateful to Dr. -

Combined Book Exhibit® Xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Welcome to the 2013 London Book Fair at Earls Court, The London Book Fair and the Combined Book Exhibit welcome you to the 7th Annual London Book Fair New Title Showcase. We are proud to present over of 300 print titles and ebook titles. We are pleased that you have taken the time to visit this special exhibit, and invite you to peruse the hundreds of titles and publishers on display. This catalogue provides you with their company, contact, and other relevant information so you can contact them after the show has ended. In addition, all titles will be included on a New Title Showcase searchable database, and can be on the Internet at http://NewTitleShowcase.com. Please take this catalogue with our compliments, and keep it along with your London Book Fair show directory as a record of what you saw, and whom you visited at the 2013 Fair. At the conclusion of the London Book Fair, this catalogue will be available on the London Book Fair web site (www.londonbookfair.co.uk), and the Combined Book Exhibit web site (www.combinedbook.com) in pdf format. Once again, thank you for visiting this showcase, and we hope you have a successful and rewarding experience at this years show. Jacks Thomas Jon Malinowski Group Exhibition Director President London Book Fair Combined Book Exhibit London Book Fair New Title Showcase 2013 Afflatus Press, Imagine Creative Ang'dora Productions, LLC Technology 15275 Collier Blvd 201-300, Naples, Florida USA 34119. Tel: 2392509220;Email: [email protected] 1000 Universal Studios Plaza, Sound Stage 17, Orlando, Web: www.readourwrites.com Florida USA 32819.