Is It Bittersweet to Eat Meat?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Veganism Through a Racial Lens: Vegans of Color Navigating Mainstream Vegan Networks

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College 5-24-2018 Veganism through a Racial Lens: Vegans of Color Navigating Mainstream Vegan Networks Iman Chatila Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Chatila, Iman, "Veganism through a Racial Lens: Vegans of Color Navigating Mainstream Vegan Networks" (2018). University Honors Theses. Paper 562. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.569 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Running head: VEGANISM THROUGH A RACIAL LENS 1 Veganism Through a Racial Lens: Vegans of Color Navigating Mainstream Vegan Networks by Iman Chatila An undergraduate honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Science degree in University Honors and Psychology. Thesis Advisor: Charles Klein, PhD, Department of Anthropology Portland State University 2018 Contact: [email protected] VEGANISM THROUGH A RACIAL LENS 2 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Introduction 4 Background 5 Methods 7 Positionality 7 Research Questions 7 Interviews & Analysis 8 Results & Discussion 8 Demographics: Race, Age, Education, & Duration of Veganism 8 Social Norms of Vegan Communities 9 Leadership & Redefining Activism 13 Food -

Animal Rights Conference 2018 ‘Strengthening the Movement’ Organized by Farm in Los Angeles, California, from 28Th of June Till 1St of July 2018

ANIMAL RIGHTS CONFERENCE 2018 ‘STRENGTHENING THE MOVEMENT’ ORGANIZED BY FARM IN LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA, FROM 28TH OF JUNE TILL 1ST OF JULY 2018 Source: FARM, for the Animal Rights The Save Movement, The Humane Attending the conference has been Conference 2018 in Los Angeles, League, The International Primate an experience rich in sense and in California Protection League, A Well-Fed World, meetings; it has been the opportunity Stop Animal Exploitation NOW!, to approach animal rights from a new, Vegan Outreach, VegFund, Veganuary, multilayered perspective, recognizing etc. The program of the conference is the variety of paths to advance the FARM logo available here. rights of animals: that of activism on the one hand, and of the many Inspiring, challenging, exciting. So ramifications and relations the animal can we summarize the Animal Rights rights movement maintains with a vast Conference of 2018, ‘Strengthening the swath of social justice issues at global Movement’, that took place from June level on the other hand. 28th till July 1st of 2018 at the Sheraton Gateway Hotel in Los Angeles, California. Marine Lercier1, Researcher at ICALP and PhD candidate at the Faculty of Law of the Autonomous University of Barcelona, could attend Opening speech to the Animal Rights Conference thanks to a scholarship granted by the 2018, preceded by a minute of silence for the animals exploited and abused worldwide organizers. The conference was organized by the Farm Animal Rights Movement 2 (FARM) and sponsored by many Dr. Milton Mills giving a presentation on myths of the most influent and human- and facts about the human diet during a Plenary Assembly at the Conference. -

Issue 22, 2018 '

ISSUE 22, 2018 ' - / 2ausa CREDITS EDITOR EDITORIAL Andrew Winstanley DESIGN Nick Withers 5 NEWS 6 FEATURES EDITOR Daniel Gambitsis POLITICS AND NEWS EDITOR COMMUNITY Cameron Leakey COMMUNITY EDITOR Emelia Masari 10 ARTS & LIFESTYLE EDITORS Rushika Bhatnagar & Chris Wong SCIENCE EDITOR ADVANCING Nandita Bhatnagar & Naomi Simon- Kumar VISUAL ARTS EDITOR & ORIGINAL DESIGN ANIMAL Daphne Zheng PUZZLES Courtesy of Puzzles, Riddles and Quizzes Society RIGHTS SOCIAL MEDIA TEAM Uvini Panditharatne CONTRIBUTORS 12 MEET Thomas Carr, Cameron Leakey, Lachlan Mitchell, Kat Tokareva, Keera Ofren, Sarah Tribble, Sheuk-Yeeng Tang, Mary CAMERON 16 Gwendolon, Sophia Santillan, Astrid Cro- sland, Emelia Masari, Brian Gu, Daniel Gambitsis, Orlando Kwok-Cameron, Rushika Bhatnagar AND JOY COVER ARTIST Kaye Kennedy ILLUSTRATORS 20 ARTS & Kaye Kennedy, Jenn Cheuk, Youngi Kim CALL FOR WRITERS AND ILLUSTRATORS! Flick us an email at [email protected] REVIEWS 23 if you’re interested in contributing. FIND US ONLINE www.craccum.co.nz COLUMNS CraccumMagazine @craccum 34 SCIENCE EDITORIAL OFFICE 4 Alfred Street, Private Bag 92019, Auckland PUZZLES ADVERTISING 36 Aaron Haugh [email protected] THE ARTICLES AND OPINIONS CONTAINED 38 WITHIN THIS MAGAZINE ARE NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF THE STAFF, AUSA OR PRINTERS. • Great discount off the RRP on most items in store* ubiq.co.nz • We buy and sell second-hand textbooks* - instant cash if you sell • Over 100,000 books in stock* - no waiting weeks for books to arrive • Open Monday to Saturday or buy securely from our website 24/7 100% Student owned - your store on campus *See in store for details 3 ' / 4 ausa ' EDITORIALEDITORIAL DUDE, WHERE’S MY EDITORIAL So: It’s that time of year again. -

Like Most Others, I Always Thought of Farm Animals As

2017- A Year of Growth and Opportunity We began the year with a brand-new team empowered And, myself along with FARM's former Managing Direc- by an uncommon sense of dedication and enthusiasm and the tor Jen Riley managed another winning animal rights confer- leadership of Eric Lindstrom, our new Marketing Director, ence (this is our 26th year!) near our nation's capital, assisted who has been doubling as Program Coordinator. by a dozen managers, including Vicki Beechler, Chen Cohen, Eric is directly supervising our leading programs of col- Chelsea Davis, Maggie Funkhouser, Deva Holub, Stepha- lecting hundreds of thousands of vegan pledges through online nie Jeanty, Elena Johnson, John Kane, Matt Marshall, Bryan views, then supporting these viewers on their vegan journey Monell, Rachel Pawelski, as well as staffers Ethan Eldreth, through weekly emails, with recipes and videos. He is ably Hayden Hamilton Hall, Ally Hinton, Eric Lindstrom, LaKia assisted by our new Social Media Manager Ally Hinton and Art Roberts, William Sidman, and "Woody" Wooden. (pgs. 10-11) Production Manager Christopher "Woody" Wooden. (pg. 3) We experienced a major loss this year, with Managing Our Staff We have been collecting more vegan pledges during dra- Director Jen Riley deciding to take a break from 13 years of matic visits to college campuses, street fairs, and concerts with intense activism with FARM, following our conference. We our custom-built outreach setup. The tours are staffed by were most fortunate to welcome Jessica Carlson as our new activists and led by our new Have We Been Lied To? Program Director of Operations starting in October. -

Is It Easy to Go VEGAN? 1) What to Eat? Where Can – I

Is it easy to go VEGAN? 1) What to eat? Where can – I find recipes? You can still enjoy your favourite food but in a vegan version! As you can enjoy many other wonderful tastes without supporting the violent industry of animal agriculture which abuses them. You can find many ideas & easy recipes in the following blogs: Veggie - Wedgie The Greek Vegan 2 Broke Vegans 2) Where can – I go shopping? You can find many vegan products [such as smoked tofu, plant-based milk & cheese, yogurts (soya or coconut based), vegan ice cream and of course meat substitutes] in all bio / organic market stores which are also selling some cruelty-free cosmetics and personal hygiene products. But you can also find some vegan products (milk, yogurt, shower-gel) in some conventional super – markets. Athens: Bamboo Vegan, the first vegan market in Greece which is located in Solonos street, near Panepistimio metro stop. Online orders possible too! Larissa: Vegan Way (They deliver throughout the whole country) Katerini: Amore bio – You can find them on Facebook with the profile name AmoreBio Katerinis. For online orders you can also check these 2 websites which have a big variety of products: www.veggie- shop24.com & Boutique Vegan Cruelty free cosmetics and hygiene products Shoes, clothes, accessories etc: Online platform All Vegan All Good & Small Greek Businesses: My Hugo Vegan – Calupi Handmade - Handmade Vegan Shoes 3) Are – there any vegan / vegan friendly restaurants – sweetshops in Greece? Athens Τrivoliι Vegan Nation Lime Bistro Zachari & Αlati Peas ΜΑΜΑTIERRA (Attention! Some choices may contain dairy) THE VEGAN FAIRIES ΓΗ – Attention, some deserts and smoothies may contain honey & the coffee may have dairy milk if you don’t mention that you want plant – based milk. -

Vegan Starter Kit Vegan Starter Kit Everything You Need to Fight Climate Change with Diet Change

VEGAN STARTER KIT VEGAN STARTER KIT EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO FIGHT CLIMATE CHANGE WITH DIET CHANGE THANK YOU. YOUR SUPPORT LITERALLY MEANS“ THE WORLD. LET’S DO THIS TOGETHER. Genesis Butler 1 VEGAN STARTER KIT CONTENTS PLEASE CONSIDER 03 | WHAT IS VEGAN? “ 04 | WHY VEGAN? MY GENERATION - THE PLANET AND FUTURE - SUSTAINABILITY - BENEVOLENCE GENERATIONS, AND - ANIMALS - HEALTH KNOW THAT WE ARE 12 | TEN COMMONLY ASKED QUESTIONS ABOUT VEGANS WORRIED ABOUT 16 | BREAKING BAD HABITS OUR FUTURE ON 17 | TEN TIPS TO GET YOU STARTED THIS PLANET. 19 | VEGAN NUTRITION 21 | MEAL IDEAS Genesis Butler 23 | WHERE TO BUY VEGAN PRODUCTS 26 | EATING OUT AS A VEGAN 27 | VEGAN INSPIRATION 29 | TEN TIPS ON NAVIGATING A NON-VEGAN WORLD 31 | WHAT NEXT? 32 | APPENDIX 2 VEGAN STARTER KIT WHAT IS VEGAN? A vegan diet contains no animal products or by-products. This includes the obvious items such as meat, fish, eggs, dairy and honey, but vegans also avoid hidden animal ingredients such as gelatin, cochineal and rennet. So, what do vegans eat?! The answer to that is: the same as everyone else, they just choose plant-based versions. For almost every animal-derived ingredient and product, there is now a vegan alternative. There are cheeses, milks, yogurts and ice creams, sausages, bacon and pepperoni. There are even steaks and burgers that look, taste and feel like meat but are made entirely from plants. All of these delicious and convenient products - and more - mean we need to make only small changes in our diet to create a huge difference in the world. -

In LOVE with Humanity

In LOVE with Humanity re-Membering the GOOD within ourselves, by remembering the GOOD lived by others … a tribute to some of humanity‘s greatest Heroes; 153 men & women who have chosen, via their brave words &/or noble deeds, to reflect the deeper Greatness residing within us all via Scaughdt an (i)am publication 1 NOTE: This work is Purpose-fully non-copyrighted, and may therefore be copied, reprinted, forwarded &/or gifted onward in whatever ways any of its readers deem fit. That having been said, the author would also like to remind anyone so doing that he has no claim of legal ownership over the images used herein. Of equal importance, it is the author‘s intent that -- just as they have been given to all for free herein, so too should these entries be freely given onward to others; fully profitless to the giver; without any additional costs or conditions attached for the recipients thereof … Thank you. 2 ―There are two kinds of heroes: those who shine in the face of great adversity – who perform amazing feats in difficult situations, and those who live among us – who do their work unceremoniously; unnoticed by many, and yet making a difference in the lives of others anyway. Heroes are often nothing more than ordinary people who perform extraordinary acts, and the mark of those heroes is not the result of their actions, but the simple fact that they have chosen to willingly serve others &/or their cause. Indeed, even if they completely fail in their attempts, the purity of their intention and the durability of their determination still shines on for others to follow. -

JVS Mag No.201 – June 2017

The pictured: jvs patron rabbi david rosen rabbis warn of spiritual & moral dangers of eating since 1966 No. 201 summer 2017 sivan 5777 meat: page 8 ‘They shall not hurt nor destroy 1 on all my holy mountain’ (Isaiah) which you can read about on page 4. Welcome to See page 6 for details of upcoming events. As always, we love hearing from the jewish you. Please do get in touch with us via [email protected] with ideas you have for vegetarian this magazine, and for our events. hat a busy few months it has been! In May we hosted Lara Smallman our 52nd Annual General Director, Jewish Vegetarian Society WMeeting. A big thank you to Ori Shavit, who joined us live from Israel via Skype to talk about her role in building the vegan movement as well as the many fantastic developments in Israel, see vegansontop.co.il to find out more about Ori. We were also joined by Gavin Fernback who spoke about his personal journey to veganism, and how he veganised his London café The Fields Beneath, which you can read all about on page 13 We were delighted to secure a double page spread in the Jewish Chronicle newspaper during National Vegetarian Week, in which I shared my top tips for going veggie, see campaigning reaches page 10 for more. new heights, p26 Recently the JVS Board met Jeffrey Cohan, Director of Jewish Veg in the US, who is a regular contributor to this magazine. We look forward to collaborating with Jewish Veg in the future on joint projects - watch this space. -

Recipes Sauces & Fixins 14 Inc

Down-To-Earth Vegan Index: Introduction 3/4 Useful to know & links 5/6 Inc. books, documentaries, youtube channels etc. Let’s start at the very beginning 7 Gadgets & Goods 8/9/10 Cleaning & Personal Products 10 Meal Ideas Breakfast ideas 11 Lunch ideas 12 Dinner ideas 13 Recipes Sauces & Fixins 14 Inc. Vegan Mayo, Ranch and Tartar sauce recipes Fabulous Festive Puff Pastry Plait 15 More Pastry Plaits 16 Inc. bacon double cheeseburger, sausage and mash and full vegan breakfast. Stovetop Sausage Casserole 17 Indulgent Chocolate Brownie 18 Crispy Baked Tofu 19 Lentil Gardeners Pie 20 Cookies (& donuts) 21 Quiche Karen 22 Mini Crust-Less Quiches 23 Luxury Hummus 24 Creamy Pasta Sauce (carbonara style) 25 Delicious Focaccia 26 Tofu Scramble & BBQ Jackfruit 27 Salads, Soups & Stews 28 Quick Tips & Tricks 29 Bibimbap & Noodle Dishes 30 Inc. morning boost ice cubes, burgers, tempeh bacon and nice cream Family Meals & Festivities 31 Inc. holiday guides and eating out Growing Food & Pesto Recipe 32 Companies We Love 33 Randoms Memes We Made 34/35/36 FAQ 37 FOR THE ANIMALS! 2 | Page © Copyright 2020 - Those Vegan Guys Down-To-Earth Vegan Introduction This publication will digitally link to content on Those Vegan Guys YouTube channel, and to other online resources. Whenever you see underlined blue text - that will be a clickable link. First and foremost, HELLO (waves), we are Paul & Jason, a vegan couple from Oldham, Greater Manchester. We first met in 1997 at college, became great friends who soon became a couple & then married in 2009. So that’s us. -

The Suffragette Movement and Vegetarianism

now in our 40th year Newsletter of the Young Indian Vegetarians Summer 2018 | Issue 61 Eva Gore-Booth The Charlotte Suffragette Despard movement and Lady Constance Vegetarianism Lytton Leonara Cohen up for animals were muzzled and ridiculed. A world where there was no empathy or mercy towards the animal kingdom also extended to a cavalier attitude Is the world moving away from towards the environment and the ecological balance the mass killing of animals in of the planet. The plundering of resources provided by nature for short term gains became respectable. slaughterhouses? Is a new dawn of Nobody thought of the consequences. Drunk with human civilisation on the horizon? arrogance and a belief that science would cure all our Throughout history great thinkers, philosophers, ills we have brought the planet to its knees. A planet spiritual leaders and even economists have spoken that had been handed over to future generations out against wanton cruelty towards animals. in a healthy state for millennia has been plundered However, the arrival of the Industrial revolution in the last 200 years - the consequences of which spelled doom for animals. Along with everything are already being felt and will jeopardise the lives that was being mechanised animals came to be of future generations. In the name of progress the seen as mere commodities and it gave birth to the human race lost its soul. idea of factory farming of animals. The dominant However against all odds tens of thousands of ideologies of the 19th Century, namely capitalism compassionate souls never gave up. In the last 50 and communism put their faith in mechanisation of years here in the UK they have campaigned day and products. -

Vernissage Jeudi 15 Mars 2018, 18H Exposition Jusqu'au 25 Avril

6 ANIMAL À PART Vernissage jeudi 15 mars 2018, 18H 8 Exposition jusqu’au 25 avril 2018 1. Nicolas Tondeux Entrée libre, lundi > vendredi, 11h - 17h 2. Célia Dubus 5 7 Yeonha Shin Maeva Chappelle, Juliette Delattre, Célia Dubus, Franck Fagel, Margaux Findinier, Stéphane Gaultier, Céline Gauthier, Claire Hiegel, Emmanuel 9 3. Margaux Findinier Jacquet, Orlane Laage, Pierre Mascret, Alice Perrin, Geoffrey Régnier, Lina 4. Maëva Chappelle Shimano-Bardai, Yeonha Shin, Nicolas Tondeux, Savina Topurska 4 5. Stéphane Gaultier 10 « On ne pourrait nier, sans contredire Qu’y a-t-il de commun entre Laïka le chien 6. Pierre Mascret l’expérience la plus quotidienne, que la vie devenu célèbre après avoir été sacrifié humaine et la vie animale ne cessent de se dans l’espace et la cochenille du colorant 7. Emmanuel Jacquet rencontrer. Qu’il soit familier, domestiqué, alimentaire E120 ? Que nous disent les 3 dressé, utilisé, exposé, ou sauvage, l’animal noms d’Attenborough ou Vinciane Despret. 8. Savina Topurska traverse continuellement notre expérience Peut-on adopter un axolotl ? Les fourmis du monde. Les intérêts en jeu dans cette tisserandes ont-elles bien précédé l’industrie 9. Geoffrey Régnier relation sont d’une grande variété, depuis textile ? Comment se ventile une termitière 2 l’intérêt purement pratique, pragmatique, et se climatise un immeuble ? Pourquoi jusqu’à l’intérêt affectif. L’enjeu, alors, n’est insulte-t-on avec des noms d’oiseaux ? 11 10. Orlane Laage plus de savoir quelle place tient et s’attribue Ce sont autant de propositions que réunit 11. Céline Gauthier l’humanité vis-à-vis de l’animalité, mais il l’exposition Animal à part. -

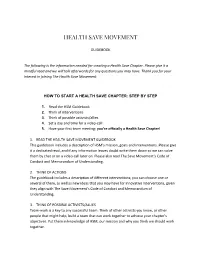

Health Save Movement

HEALTH SAVE MOVEMENT GUIDEBOOK The following is the information needed for creating a Health Save Chapter. Please give it a mindful read and we will talk afterwards for any questions you may have. Thank you for your interest in joining The Health Save Movement. HOW TO START A HEALTH SAVE CHAPTER: STEP BY STEP 1. Read the HSM Guidebook 2. Think of interventions 3. Think of possible activists/allies 4. Set a day and time for a video-call 5. Have your first team meeting; you’re officially a Health Save Chapter! 1. READ THE HEALTH SAVE MOVEMENT GUIDEBOOK This guidebook includes a description of HSM’s mission, goals and interventions. Please give it a dedicated read, and if any information leaves doubt write them down so we can solve them by chat or on a video-call later on. Please also read The Save Movement’s Code of Conduct and Memorandum of Understanding. 2. THINK OF ACTIONS The guidebook includes a description of different interventions; you can choose one or several of them, as well as new ideas that you may have for innovative interventions, given they align with The Save Movement’s Code of Conduct and Memorandum of Understanding. 3. THINK OF POSSIBLE ACTIVISTS/ALLIES Team-work is a key to any successful team. Think of other activists you know, or other people that might help, build a team that can work together to achieve your chapter’s objectives. Put them in knowledge of HSM, our mission and why you think we should work together. 4. SET A DAY AND TIME FOR A VIDEO CALL After you’ve read the guidebook and solved your doubts via chat, let’s have a video call.