MIAMI UNIVERSITY the Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We Hereby Approve the Dissertation of Lara Chatm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Ft"3Bliriiat $T;0O

ft"3bliriiaT $T;0O On a political level, LIBERA deals with the STAFF FOR THIS ISSUE: Ned Asta, contemporary woman as she joins with others in an Susan Stern, Dianna (loodwin, Lynda effort to effect a change upon her condition. Koolish, Marion Sircfman, Cathy Drey fuss, Emotionally, it explores the root level of our feelings, Janet Phe la n, Jo Ann Wash) burn, Jana Harris, those beyond the ambitions and purposes women have traditionally been conditioned to embrace. One AnfTMize and Suzanne l.oomis of our objectives is to provide a medium for the new Published by LIBERA with the sponsorship of the woman to present herself without inhibition or Associated Students of the University of California affectation. By illuminating not only women's (Berkeley) and the Berkeley Women's Collective. Sub- political and intellectual achievements, but also her scription rates: $3 for 3 issues. $1.25 per copy for fantasies, dreams, art, the dark side of her face, we issue number 1. $1 per copy for following issues. come to know more her depths, and redefine ourselves. This publication on file at the International Women's\ History Archive, 2325 Oak St., Berkeley CA. 94708. V WOMEN: We need your contributions of articles, poetry, prose, humor, drawings and photographs (black and white). If you'd like your work returned, please send a stamped, self-addressed envelope. We also welcome any interested women to join the LIBERA collective. \: 516 Eshleman Hall U. of California Berkeley, California no. 3 winter 1973 94720 (415) 642-6673 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARTICLES Jeff Desmond's Letter 3 Vietnam: A Feminist Analysis Lesbian Feminists 14 Unequal Opportunity and the Chicana Linda Peralta Aquilar 32 - Femal Heterosexuality: Its Causes and Cures Joan Hand 38 POETRY a letter to sisters in the women's movement Lynda Koolish 3 POEM FOR MY FATHER Janet Phelan 4 to my mother Susan Stern 11 LITTLE POEMS FOR SLEEPING WITH YOU Sharon Barba 13 Ben Lomond, Ca. -

Mitch Maclay Sings Just for You

MITCH MACLAY SINGS JUST FOR YOU A Play in One Act by Craig Bailey Craig Bailey 350 Woodbine Rd Shelburne VT 05482-6777 (802) 655-1197 ©2019 Craig Bailey [email protected] All rights reserved www.mitchmaclay.com CHARACTERS CHRISTOPHER WOOD Early-30s. Program Director and morning board operator for radio station TRU-92. HE capitalizes on the invisibility of his medium by dressing in casual clothing including baggy khakis, sneakers with no socks, and a comfortable T-shirt sporting the logo of an alternative band. His cynical attitude and occasionally snide veneer reflect the mind-set of an up-and- coming industry man who somehow made a wrong turn only to find himself, inexplicably, in rural Iowa. LORALIE KENT Early- to mid-20s. Evening board operator for TRU-92. SHE is dressed in simple slacks, blouse and stocking feet at rise -- with a fresh, natural, cheerful face that's wasted on the radio. Her eccentricity and inclination for seemingly pointless chatter disguise her high level of intelligence -- an asset that's thwarted only by her rose-colored naivete. SETTING Front office of radio station TRU-92 in a small Iowa town TIME A Saturday in the late-1980s 1. ACT I Scene 1 (The second story front office of radio station TRU-92 in a small Iowa town, late-1980s. The furnishings and decor are about 30 years behind the times. The overall atmosphere is drab, bordering on depressed. A doorway UC leads to a hallway. Entranceways DR and DL lead to the air studio and sales offices, respectively. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home -

Entire Issue

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 105 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 143 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, JULY 17, 1997 No. 102 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. GOVERNMENT CANNOT BUILD temporary help industry is exploding. The Chaplain, Rev. James David PROSPERITY; ONLY FREE INDI- Workers can no longer count on work- Ford, D.D., offered the following pray- VIDUALS CAN ing for the same employer for their en- er: (Mr. BALLENGER asked and was tire lives. Now is the time for Federal With all the wonderful traditions given permission to address the House policy to promote a high-wage/high- that have blessed our lives, we pray, for 1 minute and to revise and extend skill economy which values workers gracious God, that we will be more ap- his remarks.) and encourages employers to invest in preciative of the families who have Mr. BALLENGER. Mr. Speaker, I the skills and long-term productivity nurtured us along the way and given us often wonder if the other side has for- of working people. But the independent contractor pro- the very gift of life. For mothers and gotten what motivated people from vision in the Revenue Reconciliation fathers, for grandparents and relatives, every corner of the globe to come to Act would reclassify and misclassify and for all those people who fostered our shores throughout history. Indeed, American working people as independ- our growth and looked to our care, we the forefathers of the very same people offer words of thanksgiving and grati- ent contractors without wage and ben- who reflexively attack the idea of tax efit guarantees, without unemploy- tude. -

ULTIMATE BLUES GUITAR CHEAT SHEET - WRITTEN MANUAL - Page 2 of 39

ULTIMATE BLUES GUITAR CHEAT SHEET - WRITTEN MANUAL - Page 2 of 39 INTRODUCTION: This book of written lessons is an excellent tool and reference manual to develop and enhance your guitar skills. Use these instructional materials to help open up guitar avenues and to examine different chords and rhythms, lead guitar techniques, learning the fretboard, music theory,scales, and the world of playing over chord changes. If you don’t keep a practice log you want to start one for sure. A three ring binder with filler paper works best. Print out this booklet of written lessons and keep it with all other music reference materials in the three ring binder. Keep these items handy so you can refer to them when studying and practicing. Add filler paper to your binder and keep accurate records in your practice log of the items you are working on, what needs work, chord changes, progressions, songs, original material, scales, etc. Date the entries and keep track of your progress as you move forward in your guitar journey. Just like settings goals in life you want to set musical goals……and then go out there and achieve them. Remember to follow my structured curriculum, keep on practicing the right things, and keep developing your ear. Don’t overwhelm yourself by trying to take on too many new things at once. Take these lessons and techniques in stages and slow and steady wins the race. Some of the more advanced lead guitar avenues will take time to digest. One of the keys is consistency. Keep trying to put those guitars in your hands every day, even if its only for 10-15 minutes. -

Preparing Preservice Teachers for a Diverse Society: a Cosmopolitan Approach to Literacy Education Through Children's Literature

Preparing Preservice Teachers for a Diverse Society: A Cosmopolitan Approach to Literacy Education through Children's Literature Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Ryman, Cynthia Kay Citation Ryman, Cynthia Kay. (2021). Preparing Preservice Teachers for a Diverse Society: A Cosmopolitan Approach to Literacy Education through Children's Literature (Doctoral dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA). Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 14:28:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/658615 PREPARING PRESERVICE TEACHERS FOR A DIVERSE SOCIETY: A COSMOPOLITAN APPROACH TO LITERACY EDUCATION THROUGH CHILDREN’S LITERATURE by Cynthia K. Ryman __________________________ Copyright © Cynthia K Ryman 2021 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF TEACHING, LEARNING, AND SOCIOCULTURAL STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2021 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by: Cynthia K. Ryman, titled: Preparing Preservice Teachers for a Diverse Society: A Cosmopolitan Approach to Literacy Education through Children's Literature and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Kathy G. Short Date: 3/24/2021 Dr. Kathy Short Perry Gilmore Date: 3/24/2021 Dr. -

A Perfect Ending Dialogue List Draft

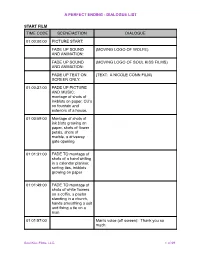

A PERFECT ENDING - DIALOGUE LIST START FILM TIME CODE SCENE/ACTION DIALOGUE 01:00:00:00 PICTURE START: FADE UP SOUND (MOVING LOGO OF WOLFE) AND ANIMATION: FADE UP SOUND (MOVING LOGO OF SOUL KISS FILMS) AND ANIMATION: FADE UP TEXT ON (TEXT: A NICOLE CONN FILM) SCREEN ONLY: 01:00:27:00 FADE UP PICTURE AND MUSIC: montage of shots of inkblots on paper, CU's on fountain and exteriors of a house. 01:00:59:00 Montage of shots of ink blots growing on paper, shots of flower petals, shots of marble, a driveway gate opening 01:01:31:00 FADE TO montage of shots of a hand writing in a calendar planner, sorting ties, inkblots growing on paper 01:01:49:00 FADE TO montage of shots of white flowers on a coffin, a pastor standing in a church, hands smoothing a suit and fixing a tie on a man 01:01:57:00 Man's voice (off screen): Thank you so much. Soul Kiss Films, LLC. 1 of 69 A PERFECT ENDING - DIALOGUE LIST TIME CODE SCENE/ACTION DIALOGUE 01:02:04:00 Montage of shots of Paris walking down a long corridor, a liquor shot is poured, a tie is undone, pills are being popped, hands rubbing jewelry, a hand scribbles in an appointment book 01:02:25:00 Montage of shots of ink blots, an S&M John and Paris in bed, the Rebecca having a drink & eating dinner, scribbling in an appointment book 01:02:37:00 CU of S&M John in S&M John: Aaaaah! bed 01:02:40:00 Montage of shots of S&M John (whispering): What are you going ink blots, S&M John to do to me? and Paris in bed, Rebecca having a drink & eating dinner, scribbling in an appointment book Paris: What do you say? 01:02:53:00 S&M John: Harder. -

Progressions

PROGRESSIONS Play along slowly CIRCLE OF FIFTHS • G-E7-A7-D7-G MORE CIRCLE OF FIFTHS • D-B7-E7-A7-D • C-A7-D7-G7-C • A-F#7-B7-E7-A • F-D7-G7-C7-F • Bd-G7-C7-F-Bd • Ed-C7-F-Bd-Ed • E-C#-F#7-B7-E 1-6 minor-4-5-1 • G-EM-C-D-G • C-AM-F-G-C • D-BM-G-A-D • E-C#M-A-B-E • F-DM-Bd-C-F 4-2M-6M-3M-5-1-6M-1 • C-AM-EM-BM-D-G-EM-G • F-DM-AM-EM-G-C-AM-C • G-EM-BM-F#M-A-D-BM-D • A-F#M-C#M-G#M-B-E-C#M-E • Bd-GM-DM-AM-C-F-DM-F • D-BM-F#M-C#M-E-A-F#M-A ROCKY TOP • G-C-G-EM-D-G (Repeat) EM-D-F-C-G- F-G-F-G • C-F-C-AM-G-C (Repeat) AM-G-Bd-F-C- Bd-C-Bd-C • D-G-D-BM-A-D (Repeat) BM-A-C-G-D- C-D-C-D • E-A-E-C#M-B-E (Repeat) C#M-B-D-A- E-D-E-D-E 1-4-5-1-4-1-5-1 • G-C-D-G-C-G-D-G • C-F-G-C-F-C-G-C • D-G-A-D-G-D-A-D • E-A-B-E-A-E-B-E • F-Bd-C-F-Bd-F-C-F • A-D-E-A-D-A-E-A • B-E-F#-B-E-B-F#-B THE BASICS AND WHY THEY’RE IMPORTANT I think it’s very important to start with the basics no matter what your level. -

Message in the Music 5 1

c. …To Messenger Of God i. He is a messenger who just wants to get his message (God’s music) out there! ii. What has he learned most recently? Learned patience… God will get you through anything! iii. Which really is the theme for this song / night iv. His music = 3 albums, songs like: “You Are”, “Love Has Come For Me”, “More Of You”, “Through All Of It”, and “Limitless” v. This is too good not to share… the rest of the interview, getting to know him: Video = Getting To Know Colton Dixon – Part 2 (3:17) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZSDJ1DVpM44 vi. Don’t you just love this guy? Love his heart? vii. Listen to his life verse again… Message in the Music 5 1. John 13:16 = “Very truly I tell you, no First Baptist Student Ministry - Wednesday, July 20, 2016 servant is greater than his master, nor is a messenger greater than the one who sent Here’s someone just like you, a former teenager, who just wants to be used by him.” (NIV) God. Meet Colton Dixon and the message behind one of his greatest songs ever viii. That should remind you that God wants to use your called “Through All Of It”… life, no matter who you are and what you’ve done! I. The Man Known As Colton Dixon II. The Struggles Known As Life a. From Average Teenager… a. We All Struggle! i. Michael Colton Dixon i. That’s a fact… we all face hard times in life ii. Born in 1991 (age 24) in Murfreesboro, TN ii. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P.