The Greater Bay Area: Integration, Differentiation and Regenerative Ecologies | Archdaily

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 1: Rank of China's 338 Prefecture-Level Cities

Appendix 1: Rank of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities © The Author(s) 2018 149 Y. Zheng, K. Deng, State Failure and Distorted Urbanisation in Post-Mao’s China, 1993–2012, Palgrave Studies in Economic History, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92168-6 150 First-tier cities (4) Beijing Shanghai Guangzhou Shenzhen First-tier cities-to-be (15) Chengdu Hangzhou Wuhan Nanjing Chongqing Tianjin Suzhou苏州 Appendix Rank 1: of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities Xi’an Changsha Shenyang Qingdao Zhengzhou Dalian Dongguan Ningbo Second-tier cities (30) Xiamen Fuzhou福州 Wuxi Hefei Kunming Harbin Jinan Foshan Changchun Wenzhou Shijiazhuang Nanning Changzhou Quanzhou Nanchang Guiyang Taiyuan Jinhua Zhuhai Huizhou Xuzhou Yantai Jiaxing Nantong Urumqi Shaoxing Zhongshan Taizhou Lanzhou Haikou Third-tier cities (70) Weifang Baoding Zhenjiang Yangzhou Guilin Tangshan Sanya Huhehot Langfang Luoyang Weihai Yangcheng Linyi Jiangmen Taizhou Zhangzhou Handan Jining Wuhu Zibo Yinchuan Liuzhou Mianyang Zhanjiang Anshan Huzhou Shantou Nanping Ganzhou Daqing Yichang Baotou Xianyang Qinhuangdao Lianyungang Zhuzhou Putian Jilin Huai’an Zhaoqing Ningde Hengyang Dandong Lijiang Jieyang Sanming Zhoushan Xiaogan Qiqihar Jiujiang Longyan Cangzhou Fushun Xiangyang Shangrao Yingkou Bengbu Lishui Yueyang Qingyuan Jingzhou Taian Quzhou Panjin Dongying Nanyang Ma’anshan Nanchong Xining Yanbian prefecture Fourth-tier cities (90) Leshan Xiangtan Zunyi Suqian Xinxiang Xinyang Chuzhou Jinzhou Chaozhou Huanggang Kaifeng Deyang Dezhou Meizhou Ordos Xingtai Maoming Jingdezhen Shaoguan -

Impact Stories from the People's Republic of China: Partnership For

Impact Stories from the People’s Republic of China Partnership for Prosperity Contents 2 Introduction Bridges Bring Boom 4 By Ian Gill The phenomenal 20% growth rate of Shanghai’s Pudong area is linked to new infrastructure— and plans exist to build a lot more. Road to Prosperity 8 By Ian Gill A four-lane highway makes traveling faster, cheaper, and safer—and brings new economic opportunities. On the Right Track 12 By Ian Gill A new railway and supporting roads have become a lifeline for one of the PRC’s poorest regions. Pioneering Project 16 By Ian Gill A model build–operate–transfer water project passes its crucial first test as the PRC encourages foreign-financed deals. Reviving a Historic Waterway 20 By Ian Gill Once smelly and black with pollution, a “grandmother” river is revived in Shanghai. From Waste to Energy 24 By Lei Kan Technology that can turn animal waste into gas is changing daily life for the better in rural PRC. From Pollution to Solution 28 By Lei Kan A project that captures and uses methane that would otherwise be released into the atmosphere during the mining process is set to become a model for thousands of coal mines across the PRC. Saving Sanjiang Wetlands 35 By Lei Kan A massive ecological preservation project is fighting to preserve the Sanjiang Plain wetlands, home to some of the richest biodiversity in the PRC . From Clean Water to Green Energy 38 By Lei Kan Two new hydropower plants in northwest PRC are providing clean, efficient energy to rural farming and herding families. -

Recovering Xiangshan Culture and the Joint Local Development

Asian Social Science; Vol. 10, No. 11; 2014 ISSN 1911-2017 E-ISSN 1911-2025 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Recovering Xiangshan Culture and the Joint Local Development Ruihui Han1 1 Humanities School, Jinan University, Zhuhai, Guangdong Province, China Correspondence: Ruihui Han, Humanities School, Jinan University, Zhuhai, Guangdong Province, China. E-mail: [email protected] Received: April 21, 2014 Accepted: May 5, 2014 Online Published: May 30, 2014 doi:10.5539/ass.v10n11p77 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v10n11p77 Abstract Xiangshan culture is a beautiful flower in Chinese modern history. The paper analyzes the origin, development, waning and influence of it. It is innovating and pioneering, and has the features of inclusiveness, mercantilism and its own historical heritage. Recovering Xiangshan culture has significant meaning for the local development of economy, society and culture. And that would also provide the positive driving force for the historic progress of all the China. Keywords: Xiangshan culture, Xiangshanese, modernization, social development, cultural development 1. Introduction The requirement of regional integration of Zhongshan, Zhuhai and Jiangmen often appeared in recent years. For example, the bill for combining Zhongshan, Zhuhai and Jiangmen as Zhujiang City was tabled by Guangdong Zhigong Party committee in January, 2014. The same bill was also tabled by the Macau member of CPPCC(Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference) in March, 2013. The city administration partition hinders the regional development of Xiangshan. Integration of the three cities can improve the cooperation with the destruction of administration partition. The bills are thought as a good idea but cannot be realized easily. -

Deciphering the Spatial Structures of City Networks in the Economic Zone of the West Side of the Taiwan Strait Through the Lens of Functional and Innovation Networks

sustainability Article Deciphering the Spatial Structures of City Networks in the Economic Zone of the West Side of the Taiwan Strait through the Lens of Functional and Innovation Networks Yan Ma * and Feng Xue School of Architecture and Urban-Rural Planning, Fuzhou University, Fuzhou 350108, Fujian, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 17 April 2019; Accepted: 21 May 2019; Published: 24 May 2019 Abstract: Globalization and the spread of information have made city networks more complex. The existing research on city network structures has usually focused on discussions of regional integration. With the development of interconnections among cities, however, the characterization of city network structures on a regional scale is limited in the ability to capture a network’s complexity. To improve this characterization, this study focused on network structures at both regional and local scales. Through the lens of function and innovation, we characterized the city network structure of the Economic Zone of the West Side of the Taiwan Strait through a social network analysis and a Fast Unfolding Community Detection algorithm. We found a significant imbalance in the innovation cooperation among cities in the region. When considering people flow, a multilevel spatial network structure had taken shape. Among cities with strong centrality, Xiamen, Fuzhou, and Whenzhou had a significant spillover effect, which meant the region was depolarizing. Quanzhou and Ganzhou had a significant siphon effect, which was unsustainable. Generally, urbanization in small and midsize cities was common. These findings provide support for government policy making. Keywords: city network; spatial organization; people flows; innovation network 1. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 341 5th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2019) Protection and Development of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Lingnan Embroidery from the Perspective of Maritime Silk Road Shujun Zheng Fuzhou University of International Studies and Trade Fuzhou, China 350001 Abstract—In the 21st century, people of insight in the Now, it has been endowed with new era connotation by this society called for saving and protecting the dying Chaozhou new grand idea. Lingnan area, which is rich in intangible embroidery techniques, and Chaozhou embroidery was cultural heritage resources of Chaozhou embroidery, lacks included in the first national intangible cultural heritage list. long-term development strategy. Lingnan area related to the However, the protection of intangible cultural heritage has maritime silk route is rich in intangible cultural heritage different views in the academic circle, and specific protection resources, which has a long history. Therefore, it is important projects of intangible cultural heritage have their bases. to take this opportunity to set up the Lingnan clan Although fashionable embroidery is highly sought after in the embroidery "Hester" brand, and the Lingnan area Maritime market in recent years, it is difficult to conceal the Silk Road and pass down depth of resources, strengthen embarrassment of the industry development. The output of Lingnan area through cultural construction of intangible Chaozhou embroidery is extremely limited, and the quantity of remaining products is not large. The market still has a large cultural heritage protection, and promote the development demand for Chaozhou embroidery products which generally and growth of the third industry, such as embroidery. -

World Bank Document

E289 Volume 3 PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA CHONGQING MUNICIPAL GOVERNMENT I HE WORLD BANK Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized CHONGQING URBAN ENVIRONMENT PROJECT NEW COMPONENTS DESIGN REVIEW AND ADVISORY SERVICES Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT VOLUME 1: WASTE WATER CONS L!DATEDEA AUGUST 2004 No. 23500321.R3.1 Public Disclosure Authorized TT IN COLLABORATION 0 INWITH ( SOGREAH I I i I I I I I I PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA CHONGQING MUNICIPAL MANAGEMENT OFFICE OF THE ROGREAH WORLD BANK'S CAPITAL 1 __ ____ __ __ ___-_ CCONS0 N5 U L I A\NN I S UTILIZATION CHONGQING URBAN ENVIRONMENT PROJECT NEW COMPONENTS CONSOLIDATED EA FOR WASTEWATER COMPONENTS IDENTIFICATION N°: 23500321.R3.1 DATE: AUGUST 2004 World Bank financed This document has been produced by SOGREAH Consultants as part of the Management Office Chongqing Urban Environment Project (CUEP 1) to the Chongqing Municipal of the World Bank's capital utilization. the Project Director This document has been prepared by the project team under the supervision of foilowing Quality Assurance Procedures of SOGREAH in compliance with IS09001. APPROVED BY DATE AUTHCP CHECKED Y (PROJECT INDEY PURPOSE OFMODIFICATION DIRECTOR) CISDI / GDM GDM B Second Issue 12/08/04 BYN Chongqing Project Management zli()cqdoc:P=v.cn 1 Office iiahui(cta.co.cn cmgpmo(dcta.cg.cn 2 The World Bank tzearlev(.worldbank.org 3 SOGREAH (SOGREAH France, alain.gueguen(.soqreah.fr, SOGREAH China) qmoysc!soQreah.com.cn CHONGQING MUNICIPALITY - THE WORLD BANK CHONGQING URBAN ENVIRONMENT PROJECT - NEW COMPONENTS CONSOLIDATED EA FOR WASTEWATER COMPONENTS CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............. .. I 1.1. -

Guide to Chengdu

AUSTRALIA CHINA YOUTH ASSOCIATION’S Guide to Chengdu 成都留学指南 Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province, is one of the largest metropolises in China. A city of great cultural import, Chengdu is the home of a number temples, historical townships, and sites of natural beauty. Coupled with great food such as the famous Sichuan hotpot and eighty per cent of the world’s panda population, Chengdu makes for one of the more memorable and unique exchange study experiences in China. ]\ Welcome! Jesse Glass / ACYA Chengdu Chapter President 2017 Contained in the following pages is a brief introduction to Chengdu. As the current chapter president of the Australia-China Youth Association (ACYA) in Chengdu, I hope that my suggestions will make for a better exchange study experience. The ACYA Chengdu chapter has been in existence and I have been in this wonderful city for almost four years. I have spent much of that time studying Chinese. Therefore, it is my sincere hope that the contents of this guide will highlight the local “ins” and “outs” of Chengdu. Chengdu is a truly unique and intriguing part of not only China but of the world at-large. It is a city that is certainly worth your consideration. An exchange study experience here will undoubtedly improve your Chinese language skills and understanding of China. ACYA GUIDE to CHENGDU — 1 ]\ What is ACYA? We strive to bridge the gap between Australia and China and to develop a generation of young professionals who are able to identify, seize and create opportunities for closer bilateral ties and greater mutual understanding between our two countries. -

November 2020 Trade Bulletin

November 9, 2020 Highlights of This Month’s Edition • Bilateral trade: In the first three quarters of 2020, the U.S. goods trade deficit was $223 billion, down 5 percent year-on-year, with agricultural exports to China up 92.8 percent from last year; in Q2 2020, the U.S. services surplus with China reached $11.7 billion, a record low due to the COVID-19 pandemic. • Policy trends in China’s economy: At the Fifth Plenum, the CCP stressed economic self-reliance and stronger domestic innovation; China’s new Export Control Law has a broad scope that creates the potential for arbitrary restrictions on Chinese exports, extraterritorial reach, and retaliation against foreign exporters and end users; China’s government introduced the digital RMB; the new Chengdu-Chongqing regional integration plan reflects a multiyear strategy of fostering economic development centered on innovation and exports. • Quarterly review of China’s economy: China reported GDP growth of 4.9 percent year-on-year in Q3, but a sluggish recovery elsewhere in the world and concerns over debt could undermine growth going forward; this year’s “Golden Week” saw a return to consumption, though indicators point to worsening income disparities. • Financial markets: Suspension of blockbuster Ant Group IPO underscores the CCP’s control over private enterprise in China. • In focus – Trends in supply chain realignment: Preliminary data and anecdotal evidence suggest the complete uprooting of supply chains out of China is unlikely, with gradual diversification emerging as a more prominent -

Supersized Cities China's 13 Megalopolises

TM Supersized cities China’s 13 megalopolises A report from the Economist Intelligence Unit www.eiu.com Supersized cities China’s 13 megalopolises China will see its number of megalopolises grow from three in 2000 to 13 in 2020. We analyse their varying stages of demographic development and the implications their expansion will have for several core sectors. The rise and decline of great cities past was largely based on their ability to draw the ambitious and the restless from other places. China’s cities are on the rise. Their growth has been fuelled both by the large-scale internal migration of those seeking better lives and by government initiatives encouraging the expansion of urban areas. The government hopes that the swelling urban populace will spend more in a more highly concentrated retail environment, thereby helping to rebalance the Chinese economy towards private consumption. Progress has been rapid. The country’s urbanisation rate surpassed 50% for the first time in 2011, up from a little over one-third just ten years earlier. Even though the growth of China’s total population will soon slow to a near standstill, the urban population is expected to continue expanding for at least another decade. China’s cities will continue to grow. Some cities have grown more rapidly than others. The metropolitan population of the southern city of Shenzhen, China’s poster child for the liberal economic reforms of the past 30 years, has nearly doubled since 2000. However, development has also spread through more of the country, and today the fastest-growing cities are no longer all on the eastern seaboard. -

U.S. Investors Are Funding Malign PRC Companies on Major Indices

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE Office of the Spokesperson For Immediate Release FACT SHEET December 8, 2020 U.S. Investors Are Funding Malign PRC Companies on Major Indices “Under Xi Jinping, the CCP has prioritized something called ‘military-civil fusion.’ … Chinese companies and researchers must… under penalty of law – share technology with the Chinese military. The goal is to ensure that the People’s Liberation Army has military dominance. And the PLA’s core mission is to sustain the Chinese Communist Party’s grip on power.” – Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo, January 13, 2020 The Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) threat to American national security extends into our financial markets and impacts American investors. Many major stock and bond indices developed by index providers like MSCI and FTSE include malign People’s Republic of China (PRC) companies that are listed on the Department of Commerce’s Entity List and/or the Department of Defense’s List of “Communist Chinese military companies” (CCMCs). The money flowing into these index funds – often passively, from U.S. retail investors – supports Chinese companies involved in both civilian and military production. Some of these companies produce technologies for the surveillance of civilians and repression of human rights, as is the case with Uyghurs and other Muslim minority groups in Xinjiang, China, as well as in other repressive regimes, such as Iran and Venezuela. As of December 2020, at least 24 of the 35 parent-level CCMCs had affiliates’ securities included on a major securities index. This includes at least 71 distinct affiliate-level securities issuers. -

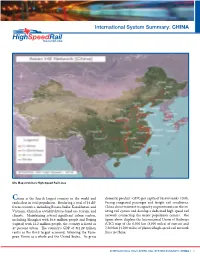

International System Summary: CHINA

International System Summary: CHINA UIC Map of China’s High-Speed Rail Lines China is the fourth largest country in the world and domestic product (GDP) per capita of $8,400 ranks 120th. ranks first in total population. Bordering a total of 14 dif- Facing congested passenger and freight rail conditions, ferent countries, including Russia, India, Kazakhstan, and China chose to invest in capacity improvements on the ex- Vietnam, China has a widely diverse land use, terrain, and isting rail system and develop a dedicated high-speed rail climate. Maintaining several significant urban centers, network connecting the major population centers. The including Shanghai with 16.6 million people and Beijing figure above displays the International Union of Railways (capital) with 12.2 million people, the country is listed as (UIC) map of the 6,300 km (3,900 miles) of current and 47 percent urban. The country’s GDP of $11.29 trillion 7,200 km (4,500 miles) of planned high-speed rail network ranks as the third largest economy, following the Euro- lines in China. pean Union as a whole and the United States.. Its gross INTERNATIONAL HIGH-SPEED RAIL SYSTEM SUMMARY: CHINA | 1 SY STEM DESCRIPTION AND HISTORY Speed Year Length Stage According to the UIC, the first high-speed rail line seg- km/h mph Opened km miles ment in the China opened in 2003 between Qinhuangdao Under Consturction: Guangzhou – Zhuhai 160 100 2011 49 30 and Shenyang. The 405 km (252 mile) segment operates (include Extend Line) at a speed of 200 km/h (125 mph) is now part of a 6,299 Wuhan – Yichang 300 185 2011 293 182 km (3,914 mile) network of high-speed rail lines stretching Tianjin – Qinhuangdao 300 185 2011 261 162 across China operating at maximum operating speeds of Nanjing – Hangzhou 300 185 2011 249 155 at least 160 km/h (100 mph) as shown in the table below. -

Min Yiming Born in June 1957 in Xi'an, China, Graduated from Xi'an

Min Yiming Born in June 1957 in Xi’an, China, graduated from Xi’an Academy of Fine Arts. Now lives and works in Xiamen, Fujian Province, China. Min also serves as President of the Chinese Academy for Beaux-Arts and Territory Development for the City of Amoy and Director of the Academic Sculpture Society for the City of Amoy in Xiamen. Prizes and Awards 2014 Meiren Public Park Beaux-Art Price-Amoy Award for Excellence, Xiamen, China 2013 Competition Urban Sculptures for Art in Companies and Public Equipments 2013 “Dance in the Wind”, sculpture selected for the 1st International Sculpture Exhibition at Pingta 2013 “Aijing”, awarded at the Third International Competition Dedicated to Landscape and Environment Planning 2011 Named by UNO as one of the top 10 designers for a territory development project in South Taiwu, China 2010 “Sea-Music”, selected for the Amy Exhibition 2008 Jury member for the First City Architecture Competition-Amoy, Xiamen, China 2006 “The law is the law”, Gold Medal, 9th International Contemporary Art Fair, Beijing, China 2004 Third Price Borders - project with Belgian-Chinese artists 1999 First Price with Le banian-Jianbin public Garden, city of Fuzhou Solo Exhibition 2015 Therefore Protein studio, London, England 2014 Mention this moment, Espace Pierre Cardin Pairs, France 2013 759 Square Chi? Hong Kong Contemporary Art Museum, Beijing, China 2009 Posture, Paragon International Center, Xiamen, China 2005 Deep Space, Nihao Art Gallery, Xiamen, China 2002 Urban Expression, Xiamen, China 1998 Square Continuous Exhibition,