View Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MLS Game Guide

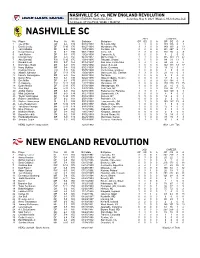

NASHVILLE SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION NISSAN STADIUM, Nashville, Tenn. Saturday, May 8, 2021 (Week 4, MLS Game #44) 12:30 p.m. CT (MyTV30; WSBK / MyRITV) NASHVILLE SC 2021 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Joe Willis GK 6-5 189 08/10/1988 St. Louis, MO 3 3 0 0 139 136 0 1 2 Daniel Lovitz DF 5-10 170 08/27/1991 Wyndmoor, PA 3 3 0 0 149 113 2 13 3 Jalil Anibaba DF 6-0 185 10/19/1988 Fontana, CA 0 0 0 0 231 207 6 14 4 David Romney DF 6-2 190 06/12/1993 Irvine, CA 3 3 0 0 110 95 4 8 5 Jack Maher DF 6-3 175 10/28/1999 Caseyville, IL 0 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 6 Dax McCarty MF 5-9 150 04/30/1987 Winter Park, FL 3 3 0 0 385 353 21 62 7 Abu Danladi FW 5-10 170 10/18/1995 Takoradi, Ghana 0 0 0 0 84 31 13 7 8 Randall Leal FW 5-7 163 01/14/1997 San Jose, Costa Rica 3 3 1 2 24 22 4 6 9 Dominique Badji MF 6-0 170 10/16/1992 Dakar, Senegal 1 0 0 0 142 113 33 17 10 Hany Mukhtar MF 5-8 159 03/21/1995 Berlin, Germany 3 3 1 0 18 16 5 4 11 Rodrigo Pineiro FW 5-9 146 05/05/1999 Montevideo, Uruguay 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 12 Alistair Johnston DF 5-11 170 10/08/1998 Vancouver, BC, Canada 3 3 0 0 21 18 0 1 13 Irakoze Donasiyano MF 5-9 155 02/03/1998 Tanzania 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 Daniel Rios FW 6-1 185 02/22/1995 Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico 0 0 0 0 18 8 4 0 15 Eric Miller DF 6-1 175 01/15/1993 Woodbury, MN 0 0 0 0 121 104 0 3 17 CJ Sapong FW 5-11 185 12/27/1988 Manassas, VA 3 0 0 0 279 210 71 25 18 Dylan Nealis DF 5-11 175 07/30/1998 Massapequa, NY 1 0 0 0 20 10 0 0 19 Alex Muyl MF 5-11 175 09/30/1995 New York, NY 3 2 0 0 134 86 11 20 20 Anibal -

PHILADELPHIA UNION V PORTLAND TIMBERS (Sept

PHILADELPHIA UNION v PORTLAND TIMBERS (Sept. 10, PPL Park, 7:30 p.m. ET) 2011 SEASON RECORDS PROBABLE LINEUPS ROSTERS GP W-L-T PTS GF GA PHILADELPHIA UNION Union 26 8-7-11 35 35 30 1 Faryd Mondragon (GK) at home 13 5-1-7 22 19 15 3 Juan Diego Gonzalez (DF) 18 4 Danny Califf (DF) 5 Carlos Valdes (DF) Timbers 26 9-12-5 32 33 41 MacMath 6 Stefani Miglioranzi (MF) on road 12 1-8-3 6 7 22 7 Brian Carroll (MF) 4 5 8 Roger Torres (MF) LEAGUE HEAD-TO-HEAD 25 Califf Valdes 15 9 Sebastien Le Toux (FW) ALL-TIME: 10 Danny Mwanga (FW) Williams G Farfan Timbers 1 win, 1 goal … 7 11 Freddy Adu (MF) Union 0 wins, 0 goals … Ties 0 12 Levi Houapeu (FW) Carroll 13 Kyle Nakazawa (MF) 14 Amobi Okugo (MF) 2011 (MLS): 22 9 15 Gabriel Farfan (MF) 5/6: POR 1, PHI 0 (Danso 71) 11 16 Veljko Paunovic (FW) Mapp Adu Le Toux 17 Keon Daniel (MF) 18 Zac MacMath (GK) 19 Jack McInerney (FW) 16 10 21 Michael Farfan (MF) 22 Justin Mapp (MF) Paunovic Mwanga 23 Ryan Richter (MF) 24 Thorne Holder (GK) 25 Sheanon Williams (DF) UPCOMING MATCHES 15 33 27 Zach Pfeffer (MF) UNION TIMBERS Perlaza Cooper Sat. Sept. 17 Columbus Fri. Sept. 16 New England PORTLAND TIMBERS Fri. Sept. 23 at Sporting KC Wed. Sept. 21 San Jose 1 Troy Perkins (GK) 2 Kevin Goldthwaite (DF) Thu. Sept. 29 D.C. United Sat. Sept. 24 at New York 11 7 4 Mike Chabala (DF) Sun. -

The Marquee Effect : a Study of the Effect of Designated Players On

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research 2016 The aM rquee effect : a study of the effect of designated players on revenue and performance in major league soccer Hannah Holub Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Part of the Economics Commons Recommended Citation Holub, Hannah, "The aM rquee effect : a study of the effect of designated players on revenue and performance in major league soccer" (2016). Honors Theses. Paper 849. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Marquee Effect: A Study of the Effect of Designated Players on Revenue and Performance in Major League Soccer by Hannah Holub Honors Thesis Submitted to Department of Economics University of Richmond Richmond, VA April 28, 2016 Advisor: Dr. Jim Monks 1 Table of Contents I. Introduction 3 II. Literature Review 7 III. Theoretical Model 12 IV. Econometric Models and Methods 16 V. Data 22 VI. Results 23 VII. Robustness 28 VIII. Conclusion 31 IX. Appendix 34 X. References 50 2 Introduction Since its formation in 1994 Major League Soccer (MLS) has slowly been gaining the momentum to reach a level of recognition similar to that of the top four sports leagues in the United States – the National Football League, the National Basketball Association, the National Hockey League, and Major League Baseball. Major League Soccer (MLS) is the top tier professional soccer league in the United States, one of only two leagues to reach that status and the only soccer league to sustain long term success.1 Made up of nineteen teams across the United States and Canada, the MLS is structured much differently than the other leagues both within the United States and internationally. -

MLS As a Sports Product – the Prominence of the World's Game in the U.S

MLS as a Sports Product – the Prominence of the World’s Game in the U.S. Stephen A. Greyser Kenneth Cortsen Working Paper 21-111 MLS as a Sports Product – the Prominence of the World’s Game in the U.S. Stephen A. Greyser Harvard Business School Kenneth Cortsen University College of Northern Denmark (UCN) Working Paper 21-111 Copyright © 2021 by Stephen A. Greyser and Kenneth Cortsen. Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. Funding for this research was provided in part by Harvard Business School. MLS as a Sports Product – the Prominence of the World’s Game in the U.S. April 8, 2021 Abstract The purpose of this Working Paper is to analyze how soccer at the professional level in the U.S., with Major League Soccer as a focal point, has developed over the span of a quarter of a century. It is worthwhile to examine the growth of MLS from its first game in 1996 to where the league currently stands as a business as it moves past its 25th anniversary. The 1994 World Cup (held in the U.S.) and the subsequent implementation of MLS as a U.S. professional league exerted a major positive influence on soccer participation and fandom in the U.S. Consequently, more importance was placed on soccer in the country’s culture. The research reported here explores the league’s evolution and development through the cohesion existing between its sporting and business development, as well as its performance. -

Onside: a Reconsideration of Soccer's Cultural Future in the United States

1 ONSIDE: A RECONSIDERATION OF SOCCER’S CULTURAL FUTURE IN THE UNITED STATES Samuel R. Dockery TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin May 8, 2020 ___________________________________________ Matthew T. Bowers, Ph.D. Department of Kinesiology Supervising Professor ___________________________________________ Elizabeth L. Keating, Ph.D. Department of Anthropology Second Reader 2 ABSTRACT Author: Samuel Reed Dockery Title: Onside: A Reconsideration of Soccer’s Cultural Future in the United States Supervising Professors: Matthew T. Bowers, Ph.D. Department of Kinesiology Elizabeth L. Keating, Ph.D. Department of Anthropology Throughout the course of the 20th century, professional sports have evolved to become a predominant aspect of many societies’ popular cultures. Though sports and related physical activities had existed long before 1900, the advent of industrial economies, specifically growing middle classes and ever-improving methods of communication in countries worldwide, have allowed sports to be played and followed by more people than ever before. As a result, certain games have captured the hearts and minds of so many people in such a way that a culture of following the particular sport has begun to be emphasized over the act of actually doing or performing the sport. One needs to look no further than the hours of football talk shows scheduled weekly on ESPN or the myriad of analytical articles published online and in newspapers daily for evidence of how following and talking about sports has taken on cultural priority over actually playing the sport. Defined as “hegemonic sports cultures” by University of Michigan sociologists Andrei Markovits and Steven Hellerman, these sports are the ones who dominate “a country’s emotional attachments rather than merely representing its callisthenic activities.” Soccer is the world’s game. -

The Effects of Players' Salary Level and a Salary Cap on the Revenue of Professional Soccer Teams in the United States And

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Undergraduate Honors Theses Student Works 5-2018 The ffecE ts of Players’ Salary Level and a Salary Cap on the Revenue of Professional Soccer Teams in the United States and England Tyler Watson Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/honors Part of the Accounting Commons, Finance and Financial Management Commons, Sports Management Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Watson, Tyler, "The Effects of Players’ Salary Level and a Salary Cap on the Revenue of Professional Soccer Teams in the United States and England" (2018). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 455. https://dc.etsu.edu/honors/455 This Honors Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Effects of Players’ Salary Level and a Salary Cap on the Revenue of Professional Soccer Teams in the United States and England By Tyler Todd Watson An Undergraduate Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the University Honors Scholars Program Honors College College of Business and Technology East Tennessee State University ___________________________________________ Tyler T. Watson Date ___________________________________________ Dr. Gary Burkette, Thesis -

The Impact of Designated Players in Major League Soccer

Superstar Salaries and Soccer Success: The Impact of Designated Players in Major League Soccer Dennis Coates Department of Economics University of Maryland, Baltimore County Bernd Frick Department of Management University of Paderborn Todd Jewell Department of Economics University of North Texas December 2012 Abstract This study estimates the relationship between production and salary structure in Major League Soccer (MLS), the highest level of professional soccer (association football) in North America. Soccer production, measured as league-points-per- game, is modeled as a function of a team’s total wage bill, the distribution of the team’s wage bill, and goals per game. Both the gini coefficient and the coefficient of variation are utilized to measure salary inequality. The results indicate that production in MLS is negatively responsive to increases in the salary inequality; this effect is consistently significant when using the coefficient of variation to measure dispersion. 1 I. Introduction Economic theory indicates that the distribution of salaries can affect the productivity of workers and firms. In the theory of tournaments, Lazear and Rosen (1981) discuss the possibility that greater salary inequality can lead to more worker effort and increased productivity. However, cohesion theory (Levine, 1991) implies firms may be able to increase the productivity of workers by equalizing salaries, since a more equal salary distribution will increase unity within the firm. The implication is that firms with more equal salary distributions will be more productive than similar firms with less equal salary structures. The present study attempts to shed light on the question of the connection between salary structure and productivity using professional sports data. -

200-242 MLS.Pdf

mls staff directory 420 Fifth Avenue, 7th Floor New York, New York 10018 Phone (212) 450-1200 Fax (212) 450-1300 www.MLSnet.com DON GARBER MLS Commissioner COMMISSIONER'S OFFICE LEGAL Commissioner Don Garber VP Business and Legal Affairs William Z. Ordower President, MLS Mark Abbott Legal Counsel Jennifer Duberstein President, SUM Doug Quinn Associate Legal Counsel Brett Lashbrook Executive VP MLS JoAnn Neale Administrator, Legal Jasmin Rivera Chief Financial Officer Sean Prendergast Sr. VP of Strategic Business Development Nelson Rodriguez BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT Special Assistant to the Commissioner Ali Curtis Exec. Vice President, SUM Kathryn Carter Executive Assistant to the Commissioner Erin Grady VP, Business Development Michael Gandler Executive Assistant to Mark Abbott Ashley Drezner Director, Online Ad Network Chris Schlosser Manager, Business Development Courtney Carter BROADCASTING Manager, Business Development Steve Jolley Executive Producer, Broadcasting/SUM Michael Cohen Manager, Business Development Anthony Rivera Director, Broadcasting Larry Tiscornia Executive Assistant, SUM Monique Beau Manager, Broadcasting Jason Saghini Executive Assistant, SUM Alyssa Enverga Coordinator, Broadcasting Johanna Rojas Consultant, SUM Dave Mosca Consultant, Digital Strategy Ahmed El-Kadars COMMUNICATIONS AND MLS INTERNET NETWORK Sr. VP, Marketing and Communications Dan Courtemanche PARTNERSHIP MARKETING Director, Communications Will Kuhns Vice President, Partnership Marketing David Wright Director, International Communications Marisabel Munoz -

Major League Soccer As a Case Study in Complexity Theory

Florida State University Law Review Volume 44 Issue 2 Winter 2017 Article 1 Winter 2017 Major League Soccer as a Case Study in Complexity Theory Steven A. Bank UCLA School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Contracts Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Other Law Commons Recommended Citation Steven A. Bank, Major League Soccer as a Case Study in Complexity Theory, 44 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 385 (2018) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol44/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MAJOR LEAGUE SOCCER AS A CASE STUDY IN COMPLEXITY THEORY STEVEN A. BANK* ABSTRACT Major League Soccer has long been criticized for its “Byzantine” roster rules and regu- lations, rivaled only by the Internal Revenue Code in its complexity. Is this criticism fair? By delving into complexity theory and the unique nature of the league, this Article argues that the traditional complaints may not apply in the context of the league’s roster rules. Effectively, critics are applying the standard used to evaluate the legal complexity found in rules such as statutes and regulations when the standard used to evaluate contractual complexity is more appropriate. Major League Soccer’s system of roster rules is the product of a contractual and organizational arrangement among the investor-operators. -

A Policy Analysis of Player Acquisition Rules in Major League Soccer

A Policy Analysis of Player Acquisition Rules in Major League Soccer Warren, Clint Illinois State University, United States of America [email protected] Aim This study provides a policy analysis of the player acquisition mechanisms utilized in Major League Soccer (MLS) in the United States. Specifically, this study focuses on three unique player acquisition policies that allow MLS clubs to spend beyond the league’s hard salary cap to bring in more talented and marketable players. The three policy changes that are the subject of this study are the 2007 Designated Player Rule (DP Rule), the 2010 expansion of the DP Rule, and the 2015 creation of general allocation money (GAM) and targeted allocation money (TAM). The aim of this research is to estimate the on and off field impact of these three player acquisition policies. As such, three primary research questions are posed. 1) Are MLS teams using these roster policies to financially compensate to performing players in the league? 2) Has the implementation of these policies created a competitive advantage for teams with larger budgets? 3) Has the increased spending allowed for by these regulations correlated with an increase in spectator attendance? Theoretical Background Since the league began play in 1996, MLS has utilized numerous roster management, game play, and financial management policies to ensure a conservative, long-term plan to grow a sustainable top division of professional soccer in the U.S. As with other North American professional sports, MLS adopted a hard salary cap and centralized mechanisms within the league to allocate players to team rosters and share league revenues to the owner-operators of individual league franchises. -

Probable Lineups a 20 86 17 0 3 1 8 10 17 27 14 6 4 5 21 3 18 6 7

SAN JOSE EARTHQUAKES v LA GALAXY (June 27, Stanford Stadium, 7:30 p.m. PT) 2015 SEASON RECORDS PROBABLE LINEUPS ROSTERS GP W-L-T PTS GF GA S.J. EARTHQUAKES Earthquakes 15 6-5-4 22 16 15 1 David Bingham (GK) at home 6 3-1-2 11 6 3 2 Ty Harden (DF) 3 Jordan Stewart (DF) 1 4 Marvell Wynne (DF) Galaxy 19 7-5-7 28 26 20 Bingham 5 Victor Bernardez (DF) on road 9 0-4-5 5 7 15 6 Shea Salinas (MF) 5 21 7 Cordell Cato (MF) LEAGUE HEAD-TO-HEAD 4 Bernardez Goodson 3 8 Chris Wondolowski (FW) ALL-TIME (57 meetings): 9 Khari Stephenson (MF) Earthquakes 18 wins (1 shootout), 75 goals… Wynne Stewart 10 Matias Perez Garcia (MF) Galaxy 27 wins (4 shootout), 89 goals…Ties 12 27 11 Innocent Emeghara (FW) Alashe 12 Mark Sherrod (FW) AT SAN JOSE (30 meetings): 14 Adam Jahn (FW) Earthquakes 13 wins (1 shootout), 43 goals … 15 JJ Koval (MF) Galaxy 10 wins (2 shootout), 39 goals … Ties 7 17 8 10 6 17 Sanna Nyassi (MF) 18 Tomas Gomez (GK) Nyassi Wondolowski Perez Garcia Salinas LAST YEAR (MLS) 19 Mike Fucito (FW) 6/28: SJ 0, LA 1 (Zardes 61) 20 Shaun Francis (DF) 21 Clarence Goodson (DF) 8/8: LA 2, SJ 2 (Zardes 29; Gonzalez 49 – Wondolowski 18; 14 22 Tommy Thompson (FW) Garcia 31) Jahn 23 Leandro Barrera (MF) 9/14: SJ 1, LA 1 (Wondolowski 66 – Gonzalez 28) 24 Steven Lenhart (FW) 7 11 27 Fatai Alashe (MF) UPCOMING MATCHES 35 Bryan Meredith (GK) EARTHQUAKES GALAXY Keane Zardes 38 Paulo Renato (DF) Sun. -

Major League Soccer Case Study an Examination Into the Future of the League

Syracuse University SURFACE Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects Projects Spring 5-1-2013 Major League Soccer Case Study An Examination into the Future of the League Matt Samost Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, and the Sports Management Commons Recommended Citation Samost, Matt, "Major League Soccer Case Study An Examination into the Future of the League" (2013). Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects. 94. https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone/94 This Honors Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Major League Soccer Case Study An Examination into the Future of the League Honors Advisor: . Honors Reader: . Matt Samost SPM 499 Honors Capstone Fall 2012 Abstract Major League Soccer has grown tremendously since its inception in 1996. The league, however, still is a work in progress. The overarching question of this case study deals with an examination into the future of the league. Will it continue to be a niche sport on the American sports landscape or will it challenge the big four leagues in the years to come? Broken into five subtopics, the case study looks to address this question by examining the league through multiple lenses in order to be able to take both an in-depth and wide look at the current condition of the league.