31-1-131-Jakobsze-Pdfa.Pdf (369.4Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SMC Security Probes Assaults by EMILY WILLETT Normal Build, Dark Hair and Saint Mary’S Editor Approximately Six Feet Tall

# — Saint Mary’s College The Observer NOTRE DAME « INDIANA VOL. XXIV NO. 15 FRIDAY , SEPTEMBER 13, 1991 THE INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER SERVING NOTRE DAME AND SAINT MARY’S SMC Security probes assaults By EMILY WILLETT normal build, dark hair and Saint Mary’s Editor approximately six feet tall. Security conducted an inves Saint Mary’s Security is in tigation of the area which was vestigating the assault of a to no avail. Saint Mary’s student which took This incident is the second place at approximately 8:30 reported attack on campus this p.m. Wednesday night on the week. On Monday evening campus. Security responded to a The victim reported that she reported assault on the was walking from her car in the walkway between McCandless Angela Athletic Facility parking Hall and the Cushwa-Leighton lot on the walkway which runs Library. While both cases are beside the building when the still under investigation, at this attacker approached her from time the two incidents are behind. believed to be unrelated. The victim said that the as “We do not have enough con sailant covered her mouth with crete evidence at this time to his hand and attempted to drag show that the incidents are as her toward a nearby tree. The sociated,” said Richard Chle- victim said she freed herself bek, Director of Safety and Se The Observer/Andrew McCloskey from the attacker, slashing his curity. Football fanatics face with her keys, and ran to Saint Mary’s Security will be McCandless Hall. increasing security presence in Football fans of all kinds came together last Saturday to show their support for the Notre Dame She described the attacker to the areas of the two attacks, football team. -

2019Collegealmanac 8-13-19.Pdf

college soccer almanac Table of Contents Intercollegiate Coaching Records .............................................................................................................................2-5 Intercollegiate Soccer Association of America (ISAA) .......................................................................................6 United Soccer Coaches Rankings Program ...........................................................................................................7 Bill Jeffrey Award...........................................................................................................................................................8-9 United Soccer Coaches Staffs of the Year ..............................................................................................................10-12 United Soccer Coaches Players of the Year ...........................................................................................................13-16 All-Time Team Academic Award Winners ..............................................................................................................17-27 All-Time College Championship Results .................................................................................................................28-30 Intercollegiate Athletic Conferences/Allied Organizations ...............................................................................32-35 All-Time United Soccer Coaches All-Americas .....................................................................................................36-85 -

Congressional Ability to Investigate Steroid Use in Major League

LeCrom et al. Page 32 THE IMPACT OF NIKE PROJECT 40/GENERATION ADIDAS PLAYERS ON MAJOR LEAGUE SOCCER Carrie W. LeCrom, John P. Selwood, Philipp Daldrup, & Mark Driscoll Carrie LeCrom, Ph.D., is the Director Abstract of Instruction and Academic Affairs at Created in 1997, the Nike Project40/Generation Adidas program encourages soccer players the Center for Sport to leave college early to sign professional contracts with Major League Soccer teams, Leadership at VCU. guaranteeing them a 3-year salary with two one-year options. In theory, if the best players Jay Selwood is the are being chosen to this program each year, they should be outperforming those who are Soccer Program drafted to MLS teams but are not a part of the program. By comparing the top draft picks Manager at the Maryland SoccerPlex within and outside the program, researchers hoped to determine whether Nike/Adidas in Boyds, Maryland. players were having a different impact on the league than their counterparts. Results showed Philipp Daldrup is a that, of 15 statistical categories analyzed, only three resulted in a statistically significant Marketing Manager difference between groups. Though Nike/Adidas players were outperforming players who at BASF Coatings were not a part of the program, they were not doing so at a rate to justify the claim that they GmbH in Münster, Germany. have a greater impact on the league. Mark J. Driscoll, M.Ed., is the Assistant Box Office Keywords: Major League Soccer, Nike Project 40, Generation Adidas, MLS SuperDraft Manager at the John Paul Jones Arena in Charlottesville, LeCrom, C. -

Vader Couple's Arraignment Delayed Doctor's Office Steps Away From

$1 Weekend Edition Saturday, Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com Dec. 6, 2014 Napavine Heartbreak Ski Season Underway Tigers Fall in Title Game / Sports 1 at White Pass / Main 5 Vader Couple’s Arraignment Delayed DELAYED: Brenda Wing Danny Wing, 26, and his ard L. Brosey continued the ar- it is “best” for him to continue the one who’s in jail, so you’re wife, Brenda Wing, 27, were raignment a week. his client’s arraignment as well. the one I’m concerned with,” Gets New Attorney; each scheduled to be arraigned “If Mr. Crowley is not here Before Pascoe stopped him Brosey said. Arraignment Will Take for the Oct. 5 death of Jasper at that time, I’m not inclined to from speaking, Danny Wing According to court docu- Henderling-Warner, who they continue a hearing … such as said his previously counsel was ments, the Wings’ timeline of Place Next Week had been caring for at the time. appointing an attorney to repre- “set up” by Brenda Wing’s family. events don’t quite match up — The both face a charge of sent your interests,” Brosey said. Danny Wing said he had no By Kaylee Osowski including when they picked up homicide by abuse, but their ar- Danny Wing has retained problem with the continuance Jasper to care for him. Both say [email protected] raignments were pushed back to representation with Vancouver- when asked by the judge if he they were only caring for him Dec. 11. Brenda Wing said since based defense attorney Todd was OK with the request. -

Major League Soccer-Historie a Současnost Bakalářská Práce

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Fakulta sportovních studií Katedra sportovních her Major League Soccer-historie a současnost Bakalářská práce Vedoucí bakalářské práce: Vypracoval: Mgr. Pavel Vacenovský Zdeněk Bezděk TVS/Trenérství Brno, 2013 Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci vypracoval samostatně a na základě literatury a pramenů uvedených v použitých zdrojích. V Brně dne 24. května 2013 podpis Děkuji vedoucímu bakalářské práce Mgr. Pavlu Vacenovskému, za podnětné rady, metodické vedení a připomínky k této práci. Úvod ........................................................................................................................ 6 1. FOTBAL V USA PŘED VZNIKEM MLS .................................................. 8 2. PŘÍPRAVA NA ÚVODNÍ SEZÓNU MLS ............................................... 11 2.1. Tisková konference MLS ze dne 17. října 1995..................................... 12 2.2. Tisková konference MLS ze dne 18. října 1995..................................... 14 2.3. První sponzoři MLS ............................................................................... 15 2.4. Platy Marquee players ............................................................................ 15 2.5. Další události v roce 1995 ...................................................................... 15 2.6. Drafty MLS ............................................................................................ 16 2.6.1. 1996 MLS College Draft ................................................................. 17 2.6.2. 1996 MLS Supplemental Draft ...................................................... -

MLS Game Guide

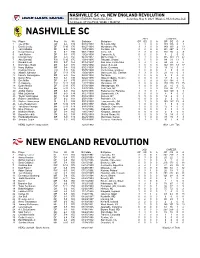

NASHVILLE SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION NISSAN STADIUM, Nashville, Tenn. Saturday, May 8, 2021 (Week 4, MLS Game #44) 12:30 p.m. CT (MyTV30; WSBK / MyRITV) NASHVILLE SC 2021 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Joe Willis GK 6-5 189 08/10/1988 St. Louis, MO 3 3 0 0 139 136 0 1 2 Daniel Lovitz DF 5-10 170 08/27/1991 Wyndmoor, PA 3 3 0 0 149 113 2 13 3 Jalil Anibaba DF 6-0 185 10/19/1988 Fontana, CA 0 0 0 0 231 207 6 14 4 David Romney DF 6-2 190 06/12/1993 Irvine, CA 3 3 0 0 110 95 4 8 5 Jack Maher DF 6-3 175 10/28/1999 Caseyville, IL 0 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 6 Dax McCarty MF 5-9 150 04/30/1987 Winter Park, FL 3 3 0 0 385 353 21 62 7 Abu Danladi FW 5-10 170 10/18/1995 Takoradi, Ghana 0 0 0 0 84 31 13 7 8 Randall Leal FW 5-7 163 01/14/1997 San Jose, Costa Rica 3 3 1 2 24 22 4 6 9 Dominique Badji MF 6-0 170 10/16/1992 Dakar, Senegal 1 0 0 0 142 113 33 17 10 Hany Mukhtar MF 5-8 159 03/21/1995 Berlin, Germany 3 3 1 0 18 16 5 4 11 Rodrigo Pineiro FW 5-9 146 05/05/1999 Montevideo, Uruguay 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 12 Alistair Johnston DF 5-11 170 10/08/1998 Vancouver, BC, Canada 3 3 0 0 21 18 0 1 13 Irakoze Donasiyano MF 5-9 155 02/03/1998 Tanzania 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 Daniel Rios FW 6-1 185 02/22/1995 Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico 0 0 0 0 18 8 4 0 15 Eric Miller DF 6-1 175 01/15/1993 Woodbury, MN 0 0 0 0 121 104 0 3 17 CJ Sapong FW 5-11 185 12/27/1988 Manassas, VA 3 0 0 0 279 210 71 25 18 Dylan Nealis DF 5-11 175 07/30/1998 Massapequa, NY 1 0 0 0 20 10 0 0 19 Alex Muyl MF 5-11 175 09/30/1995 New York, NY 3 2 0 0 134 86 11 20 20 Anibal -

2017 United Soccer League Media Guide

Table of Contents LEAGUE ALIGNMENT/IMPORTANT DATES ..............................................................................................4 USL EXECUTIVE BIOS & STAFF ..................................................................................................................6 Bethlehem Steel FC .....................................................................................................................................................................8 Charleston Battery ......................................................................................................................................................................10 Charlotte Independence ............................................................................................................................................................12 Colorado Springs Switchbacks FC .......................................................................................................................................14 FC Cincinnati .................................................................................................................................................................................16 Harrisburg City Islanders ........................................................................................................................................................18 LA Galaxy II ..................................................................................................................................................................................20 -

Chastain, Dooley, Doyle, Harkes, Kraft, Mankameyer, Messersmith

MINUTES UNITED STATES SOCCER FEDERATION, INC. BOARD OF DIRECTOR’S MEETING TELEPHONE CONFERENCE JANUARY 10, 2007 5:00 P.M. CENTRAL TIME ______________________________________________________________________________ VIA TELEPHONE: Sunil Gulati, Mike Edwards, Bill Goaziou, Bill Bosgraaf, Paul Caligiuri, Dr. S. Robert Contiguglia, Daniel Flynn, Don Garber, Burton Haimes, Linda Hamilton, Brooks McCormick, Mike McDaniel, Larry Monaco, Kevin Payne. REGRETS: Peter Vermes. IN ATTENDANCE: Jay Berhalter, Timothy Pinto, Gregory Fike, Asher Mendelsohn. ______________________________________________________________________________ President Gulati called the meeting to order at 5:00 p.m. Asher Mendelsohn took roll call and announced that a quorum was present. PRESIDENT’S/SECRETARY GENERAL’S REPORT Dan Flynn updated the Board regarding the negotiation of the split between SUM and U.S. Soccer of television revenues. He also informed the Board that there was an agreement in principle with SUM. President Gulati informed the Board that there had been negotiations with MNT interim coach Bob Bradley regarding the terms to which he might be named the permanent MNT coach. He also told the Board that U.S. Soccer needed an update of the progress on creating a Women’s Professional Soccer League by the 2007 AGM. He emphasized that it is important to FIFA that the league be structured and supported in such a way that guarantees that the league will succeed for the long-term. TREASURER’S REPORT Bill Goaziou informed the Board that U.S. Soccer is in a strong financial position. UNFINISHED BUSINESS Tim Pinto updated the Board regarding the fact that the U.S. Futsal Federation was removed as a member of U.S. -

Fox Sports Highlights – 3 Things You Need to Know

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Wednesday, Sept. 17, 2014 FOX SPORTS HIGHLIGHTS – 3 THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW NFL: Philadelphia Hosts Washington and Dallas Meets St. Louis in Regionalized Matchups COLLEGE FOOTBALL: No. 4 Oklahoma Faces West Virginia in Big 12 Showdown on FOX MLB: AL Central Battle Between Tigers and Royals, Plus Dodgers vs. Cubs in FOX Saturday Baseball ******************************************************************************************************* NFL DIVISIONAL MATCHUPS HIGHLIGHT WEEK 3 OF THE NFL ON FOX The NFL on FOX continues this week with five regionalized matchups across the country, highlighted by three divisional matchups, as the Philadelphia Eagles host the Washington Redskins, the Detroit Lions welcome the Green Bay Packers, and the San Francisco 49ers play at the Arizona Cardinals. Other action this week includes the Dallas Cowboys at St. Louis Rams and Minnesota Vikings at New Orleans Saints. FOX Sports’ NFL coverage begins each Sunday on FOX Sports 1 with FOX NFL KICKOFF at 11:00 AM ET with host Joel Klatt and analysts Donovan McNabb and Randy Moss. On the FOX broadcast network, FOX NFL SUNDAY immediately follows FOX NFL KICKOFF at 12:00 PM ET with co-hosts Terry Bradshaw and Curt Menefee alongside analysts Howie Long, Michael Strahan, Jimmy Johnson, insider Jay Glazer and rules analyst Mike Pereira. SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 21 GAME PLAY-BY-PLAY/ANALYST/SIDELINE COV. TIME (ET) Washington Redskins at Philadelphia Eagles Joe Buck, Troy Aikman 24% 1:00PM & Erin Andrews Lincoln Financial Field – Philadelphia, Pa. MARKETS INCLUDE: Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Washington, Miami, Raleigh, Charlotte, Hartford, Greenville, West Palm Beach, Norfolk, Greensboro, Richmond, Knoxville Green Bay Packers at Detroit Lions Kevin Burkhardt, John Lynch 22% 1:00PM & Pam Oliver Ford Field – Detroit, Mich. -

MEDIA GUIDE 2019 Triple-A Affiliate of the Seattle Mariners

MEDIA GUIDE 2019 Triple-A Affiliate of the Seattle Mariners TACOMA RAINIERS BASEBALL tacomarainiers.com CHENEY STADIUM /TacomaRainiers 2502 S. Tyler Street Tacoma, WA 98405 @RainiersLand Phone: 253.752.7707 tacomarainiers Fax: 253.752.7135 2019 TACOMA RAINIERS MEDIA GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Front Office/Contact Info .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Cheney Stadium .....................................................................................................................................................6-9 Coaching Staff ....................................................................................................................................................10-14 2019 Tacoma Rainiers Players ...........................................................................................................................15-76 2018 Season Review ........................................................................................................................................77-106 League Leaders and Final Standings .........................................................................................................78-79 Team Batting/Pitching/Fielding Summary ..................................................................................................80-81 Monthly Batting/Pitching Totals ..................................................................................................................82-85 Situational -

Paolo Delpiccolo, the Team Morning, and I Said, ‘Are You Ready for the Captain, Has Been with Loucity Through Playoffs?’” Hackwork Remembers

LouCity Program Ad 2020 b.pdf 1 8/24/20 12:04 PM WE NEED OFFICIAL PARTNER OF TO BENOWNOW MOREMORE THANTHAN EVEREVER Prosource® helps companies large and small optimize processes, reduce costs, and drive profits through industry-leading C Office Equipment, Document Automation, M and Technology Solutions, delivered with Y CM Just as LouCity playersan unmatched work together customer on experience. the field, MY we work together in innovative ways with businesses, CY individuals, nonprofits and government orgs to CMY empower individuals and families in our community K to achieve their fullest potential. We mean it when we say that with your help, we will create a better – more equitable future for all – right here at home! Go LouCity! totalprosource.com I 888.698.0763 Cincinnati I Dayton I Louisville I Lexington I Huntington I Charleston metrounitedway.org/2020 IN THIS ISSUE GAME PREVIEW 04 LouCity gets playoff-ready; 'that's just what we do here' TEAM ROSTERS 05 A look at team rosters for Louisville City FC and Pittsburgh Riverhounds SC LYNN FAMILY STADIUM 06 Key details about LouCity's new home EASTERN CONFERENCE STANDINGS 07 Where LouCity currently stands in the Eastern Conference JOHN HACKWORTH 08 Meet Louisville City FC's head coach LOUCITY STAFF 10-11 Louisville City's Coaches, Front Office, Technical Staff, & Medical Staff MEET THE TEAM 13-17 Player profiles for every athlete PLAYOFF BRACKET 20 USL Championship 2020 playoffs bracket COMMUNITY AND CHAMBER PARTNERS 28 A listing of Louisville City's business and civic partners 03 LOUCITY GETS PLAYOFF-READY; 'THAT'S JUST WHAT WE DO HERE' By Maggie Wesley The postseason brings a different sort of himself to LouCity’s culture. -

Seoul Calgary 1988

24, Ocean City, N.J. (Eight w/coxswain) "Peg" Mallery, 26, Delhi, N.Y. (Eight (Smallbore Rifle, Prone) / *Darius Young, /John Riley, 24, Coventry, R.l. (Sweeps w/coxswain) / Anne Marden, 29, Con 50, Winterburn, Alberta, Canada (Free spare) / Raoul Rodriguez, 25, New cord, Mass. (Single sculls) / Jennie Pistol) Orleans, La. (Four w/o coxswain) / John Marshall, 27, Durham, N.H. (Quad) I *Young is an American citizen living in "Jack" Rusher, 21, Westwood, Mass. Anne Martin, 26, Cambridge, Mass. Canada. (Eight w/coxswain) / Jon Smith, 26, (Quad) / Stephanie Maxwell, 24, Swampscott, Mass. (Eight w/coxswain) / Somerville, N.J. (Eight w/coxswain) / Mixed Greg Springer, 27, Newport Beach, Ca Abby Peck, 31, Waverly, Pa. (Eight Brian Ballard, 27, Fort Benning, Ga. lif. (Sculls spare) I Kevin Still, 27, New w/coxswain) I *Kimberly Santiago, 26, (Trap) / Daniel Carlisle, 32, Corona, Ca Rochelle, N.Y. (Double sculls) / John Madison, Wis. (Four w/coxswain) / Anna lif. (Trap; Skeet) / #Terry Carlisle, 34, Strotbeck, 31, Margate, N.J. (Quad) / Seaton, 24, Manhattan, Kan. (Eight Downey, Calif. (Skeet) / Matt Dryke, 30, Andy Sudduth, 27, Cambridge, Mass. w/coxswain) / Ann Strayer, 28, Belmont, Redmond, Wash. (Skeet) / George Haas (Single sculls) I Theodore "Ted" Mass. (Quad spare) / Juliet Thompson, III, 25, Gainesville, Fla. (Trap) I Carolyn Swinford, 28, Piedmont, Calif. (Sweeps 21, Medfield, Mass. (Eight w/coxswain) Koch, 21, Duncan, Okla. (Trap) / spare) / John Terwilliger, 30, Cincinnati, / Kristen Thorsness, 28, Anchorage, Richard "Rick" Smith, 38, Redmond, Ohio (Four w/coxswain) I Mike Teti, 31, Alaska (Sweeps spare) I Cathy Tippett, Wash. (Skeet) Upper Darby, Pa. (Eight w/coxswain) / 31, Irvine, Calif.