Congressional Ability to Investigate Steroid Use in Major League

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Major League Soccer-Historie a Současnost Bakalářská Práce

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Fakulta sportovních studií Katedra sportovních her Major League Soccer-historie a současnost Bakalářská práce Vedoucí bakalářské práce: Vypracoval: Mgr. Pavel Vacenovský Zdeněk Bezděk TVS/Trenérství Brno, 2013 Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci vypracoval samostatně a na základě literatury a pramenů uvedených v použitých zdrojích. V Brně dne 24. května 2013 podpis Děkuji vedoucímu bakalářské práce Mgr. Pavlu Vacenovskému, za podnětné rady, metodické vedení a připomínky k této práci. Úvod ........................................................................................................................ 6 1. FOTBAL V USA PŘED VZNIKEM MLS .................................................. 8 2. PŘÍPRAVA NA ÚVODNÍ SEZÓNU MLS ............................................... 11 2.1. Tisková konference MLS ze dne 17. října 1995..................................... 12 2.2. Tisková konference MLS ze dne 18. října 1995..................................... 14 2.3. První sponzoři MLS ............................................................................... 15 2.4. Platy Marquee players ............................................................................ 15 2.5. Další události v roce 1995 ...................................................................... 15 2.6. Drafty MLS ............................................................................................ 16 2.6.1. 1996 MLS College Draft ................................................................. 17 2.6.2. 1996 MLS Supplemental Draft ...................................................... -

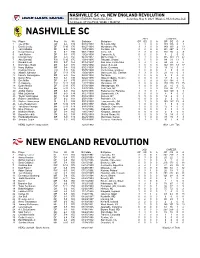

MLS Game Guide

NASHVILLE SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION NISSAN STADIUM, Nashville, Tenn. Saturday, May 8, 2021 (Week 4, MLS Game #44) 12:30 p.m. CT (MyTV30; WSBK / MyRITV) NASHVILLE SC 2021 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Joe Willis GK 6-5 189 08/10/1988 St. Louis, MO 3 3 0 0 139 136 0 1 2 Daniel Lovitz DF 5-10 170 08/27/1991 Wyndmoor, PA 3 3 0 0 149 113 2 13 3 Jalil Anibaba DF 6-0 185 10/19/1988 Fontana, CA 0 0 0 0 231 207 6 14 4 David Romney DF 6-2 190 06/12/1993 Irvine, CA 3 3 0 0 110 95 4 8 5 Jack Maher DF 6-3 175 10/28/1999 Caseyville, IL 0 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 6 Dax McCarty MF 5-9 150 04/30/1987 Winter Park, FL 3 3 0 0 385 353 21 62 7 Abu Danladi FW 5-10 170 10/18/1995 Takoradi, Ghana 0 0 0 0 84 31 13 7 8 Randall Leal FW 5-7 163 01/14/1997 San Jose, Costa Rica 3 3 1 2 24 22 4 6 9 Dominique Badji MF 6-0 170 10/16/1992 Dakar, Senegal 1 0 0 0 142 113 33 17 10 Hany Mukhtar MF 5-8 159 03/21/1995 Berlin, Germany 3 3 1 0 18 16 5 4 11 Rodrigo Pineiro FW 5-9 146 05/05/1999 Montevideo, Uruguay 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 12 Alistair Johnston DF 5-11 170 10/08/1998 Vancouver, BC, Canada 3 3 0 0 21 18 0 1 13 Irakoze Donasiyano MF 5-9 155 02/03/1998 Tanzania 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 Daniel Rios FW 6-1 185 02/22/1995 Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico 0 0 0 0 18 8 4 0 15 Eric Miller DF 6-1 175 01/15/1993 Woodbury, MN 0 0 0 0 121 104 0 3 17 CJ Sapong FW 5-11 185 12/27/1988 Manassas, VA 3 0 0 0 279 210 71 25 18 Dylan Nealis DF 5-11 175 07/30/1998 Massapequa, NY 1 0 0 0 20 10 0 0 19 Alex Muyl MF 5-11 175 09/30/1995 New York, NY 3 2 0 0 134 86 11 20 20 Anibal -

PHILADELPHIA UNION V PORTLAND TIMBERS (Sept

PHILADELPHIA UNION v PORTLAND TIMBERS (Sept. 10, PPL Park, 7:30 p.m. ET) 2011 SEASON RECORDS PROBABLE LINEUPS ROSTERS GP W-L-T PTS GF GA PHILADELPHIA UNION Union 26 8-7-11 35 35 30 1 Faryd Mondragon (GK) at home 13 5-1-7 22 19 15 3 Juan Diego Gonzalez (DF) 18 4 Danny Califf (DF) 5 Carlos Valdes (DF) Timbers 26 9-12-5 32 33 41 MacMath 6 Stefani Miglioranzi (MF) on road 12 1-8-3 6 7 22 7 Brian Carroll (MF) 4 5 8 Roger Torres (MF) LEAGUE HEAD-TO-HEAD 25 Califf Valdes 15 9 Sebastien Le Toux (FW) ALL-TIME: 10 Danny Mwanga (FW) Williams G Farfan Timbers 1 win, 1 goal … 7 11 Freddy Adu (MF) Union 0 wins, 0 goals … Ties 0 12 Levi Houapeu (FW) Carroll 13 Kyle Nakazawa (MF) 14 Amobi Okugo (MF) 2011 (MLS): 22 9 15 Gabriel Farfan (MF) 5/6: POR 1, PHI 0 (Danso 71) 11 16 Veljko Paunovic (FW) Mapp Adu Le Toux 17 Keon Daniel (MF) 18 Zac MacMath (GK) 19 Jack McInerney (FW) 16 10 21 Michael Farfan (MF) 22 Justin Mapp (MF) Paunovic Mwanga 23 Ryan Richter (MF) 24 Thorne Holder (GK) 25 Sheanon Williams (DF) UPCOMING MATCHES 15 33 27 Zach Pfeffer (MF) UNION TIMBERS Perlaza Cooper Sat. Sept. 17 Columbus Fri. Sept. 16 New England PORTLAND TIMBERS Fri. Sept. 23 at Sporting KC Wed. Sept. 21 San Jose 1 Troy Perkins (GK) 2 Kevin Goldthwaite (DF) Thu. Sept. 29 D.C. United Sat. Sept. 24 at New York 11 7 4 Mike Chabala (DF) Sun. -

U12 Boys Generation Adidas Cup Atlanta, Georgia November 29 – December 1, 2019

U12 Boys Generation Adidas Cup Atlanta, Georgia November 29 – December 1, 2019 Day 1 The Whitecaps Academy Centre team composing of 9 players from the Alberta Whitecaps Academy Centre network and 1 player from the Saskatchewan Academy Centre network arrived in Georgia, Atlanta to compete at the U12 MLS Generation Adidas Cup competition. The team were placed in the MLS Affiliate division in a group consisting of Minnesota United, Houston Dynamo and DC United. The boys opened up their tournament with games against Minnesota United and Houston Dynamo. Both teams proved to be excellent opposition for the boys but they held their own and scored a couple of goals through Osagie Aihobaku and Milan Patik. Osagie scored an excellent individual goal while Milan Patik finished off a clever team move. The games were played at a tempo and intensity that challenged the boys in all pillars of the game. Day 2 The boys had an early start for the first of three games. They played against DC United and got their reward for some excellent work out of possession through a goal from Dominic Joseph. DC United came back though in the second half and deservedly scored a couple of goals. Whitecaps then played against Boise Timbers in the play offs and despite not playing particularly well in this game, the boys managed to grind out a win on penalty kicks after a tie. Osagie scoring another skillful goal in this game. The team then saved their best performance for the semi-final against New York Red Bulls. Matching their skillful opponents, the game swung to and fro with chances at either end. -

Houapeu Becomes First Retriever Drafted Into MLS

14 FEBRUARY 1, 2011 THE RETRIEVER WEEKLY Houapeu becomes first Retriever drafted into MLS Corey Johns — TRW Levi Houapeu took the men’s soccer team to a level they’ve never been to before, and now he is the first ever to play in the MLS, drafted by the Philadelphia Union with the 41st overall pick. the team drafted, and was greeted by the York Red Bulls, Chicago Fire, Vancouver no-brainer for our pick when he was still go in and just find a role on his new team Corey Johns S.O.B.'s, Philadelphia Union's fans, an White Caps, Portland Timbers, and, the eligible who we were going to draft and and says he is going into training camp EDITORIAL STAFF experience Houapeu simply said "was a team that drafted him, the Philadelphia I think we got fortunate that he fell as far "open minded and will do what ever I great feeling." Union. as he did." can to help the team. But at the end of On January 13, 2011, Major League After a season in which Houapeu led At one point, several draft projections During the 2010 season Houapeu was the day, I want to score goals. No matter Soccer held their 12th annual MLS Su- UMBC to their first-ever second round had the 21-year-old Houapeu being not worried about his future in the MLS where they put me, I will find a way to perDraft at the Baltimore Convention appearance in the NCAA tournament by drafted as high as number 10 overall, and he was not worried about finding put the ball in the back of the net." Center. -

Download a Copy of the 2019 Soccer

“To Catch a Foul Ball You Need a Ticket to the Game” - Dr. G. Lynn Lashbrook January 11-12, 2019 DURING THE MLS SuperDraft The Global Leader in Sports Business Education | SMWW.com SOCCER CAREER CONFERENCE AGENDA NOTES Friday, January 11th 10am-noon Registration open at Marriott Marquis 11:30am-3pm MLS Super Draft at McCormick Place 4-6:00pm SMWW Welcome Reception at Kroll’s South Loop, 1736 S Michigan Ave Saturday, January 12th - Conference @ Marriott Marquis 8:00am PRE-GAME: Registration Opens 8:45am KICK-OFF: Welcome and Opening Remarks Dr. Lynn Lashbrook, SMWW President & Founder Dr. Lashbrook, President & Founder of Sports Management Worldwide, the first ever online sports management school with a mission to educate sports business executives. SMWW, under Dr. Lashbrook’s guidance, offers a global sports faculty with students from over 162 countries. In addition, Dr. Lashbrook is an NFL registered Agent having personally represented over 100 NFL clients including current Miami Dolphins Quarterback Matt Moore and Minnesota Vikings Quarterback, Kyle Sloter. Lynn is President of the SMWW Agency with over 200 Agent Advisors worldwide representing hundreds of athletes. Dr. Lashbrook continues to spearhead an effort to bring Major League Baseball to Portland, Oregon. He led the lobbying efforts that resulted in a $150 million construction bill for a new baseball stadium. Under his leadership, the group secured legislative action to subsidize a new stadium with ballplayers payroll taxes. Due to this campaign, a 25,000- seat stadium in the heart of the city was revitalized rather than torn down, now home to the MLS Portland Timbers. -

Eligibility Rules

Chapter 6 Christopher R. Deubert I. Glenn Cohen Holly Fernandez Lynch Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics at Harvard Law School Eligibility Rules Each of the leagues has rules governing when individuals become eligible to play in their leagues. While we fully acknowledge the unique nature and needs of the leagues and their athletes, we believe the leagues can learn from the other leagues’ policies. Leagues’ eligibility rules affect player health in two somewhat opposite directions: (1) by potentially forcing some players who might be ready to begin a career playing for the leagues to instead continue playing in amateur or lesser professional leagues with less (or no) compensation and at the risk of being injured; and, (2) by protecting other players from entering the leagues before they might be physically, intellectually, or emotionally ready. As will be shown, the NCAA’s Bylaws are an impor- tant factor in considering the eligibility rules and their effects on player health and thus must be included in this discussion. This issue too is discussed in our Recommendations. 206. \ Comparing Health-Related Policies & Practices in Sports In this Chapter we explain each of the leagues’ eligibility Nevertheless, the leagues’ eligibility rules have been gener- rules as well as the rules’ relationship to player health, if ally treated as not subject to antitrust scrutiny. Certain any. But first, we provide: (1) information on the eligibil- collective actions by the clubs are exempt from antitrust ity rules’ legal standing; (2) general information about laws under what is known as the non-statutory labor the leagues’ drafts that correspond to their eligibility exemption. -

Jan12it Is Superdraft Morning Feel the Excitement? the Hum Yeah This Chart Is Shaping up to Be an Interesting Ride Tomorrow

Jan12It is SuperDraft morning Feel the excitement? The hum Yeah this chart is shaping up to be an interesting ride tomorrow. Teams are within Baltimore as we talk getting geared up as this thing.This want be my final jeer chart as this SuperDraft. Today I?¡¥m going board and will be doing a two round version,nfl jersey wholesale. I know I?¡¥ve done now four of these things barely its something I enjoy a lot during the off season. It may be over kill aboard my part to do as much as I do merely with each passing week current information comes out alternatively I chat to alter folks approximately the alliance that aid form my opinions here so changes must be made.I?¡¥ve had a lot of fun this year with this chart probably as its allowed me to help out aboard other venues favor SBnation.com and more recently aboard FCDallas.com. I try my best what can I say,football jersey maker.Below is my two circular ridicule draft I?¡¥ll have adding comments under as I think there longing be some trades that jolt this plenary thing up. Should any colossal trade come down within the morning I?¡¥ll dispute it and what it longing mean as the blueprint at that point. For now the order is where it?¡¥s been by as a pair weeks immediately so as contentions sake, nothing is changing and this is how I see it playing out tomorrow.2011 WVH Mock Draft(* = Generation adidas)1. Vancouver Whitecaps ??Perry Kitchen*, M, AkronA present leader within the house is Kitchen. -

Press Release Contact: Sean Doyle, Director of Social Media [email protected] 484-269-0319

Reading United A.C. 3103 Paper Mill Rd. Wyomissing, PA 19610 www.readingunitedac.com Press Release Contact: Sean Doyle, Director of Social Media [email protected] 484-269-0319 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Former Reading United stars hear names called at 2017 MLS SuperDraft Storm, Delgado and Mfeka selected by professional clubs READING, PA (January 13, 2016) – For the eighth consecutive year, Reading United A.C. saw former players selected at Major League Soccer’s SuperDraft which was conducted in Los Angeles, California earlier today. Colton Storm, Guillermo Delgado and Lindo Mfeka, who each spent time in Reading on their path to professional soccer, heard their names called during annual draft. Since 2008, 32 former Reading United players have been selected in the MLS SuperDraft. Colton Storm, a defender who featured in eleven games for Reading in 2014 & 2015, was selected in the first round of the SuperDraft by Sporting Kansas City with the 14th overall selection. A native of Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, Storm is the 19th Reading United player to be selected in the first round of the MLS SuperDraft. A former Philadelphia Union Academy player, Storm played collegiately with the University of North Carolina, where he earned All-Atlantic Coast Conference Second Team honors in 2016. Former Reading United forward Guillermo Delgado was selected with the 5th pick in the second round (27th overall) by the Chicago Fire. The native Tres Cantos, Spain, Delgado spent the 2014 season with Reading, playing in nine matches and scoring two goals. The former United standout starred for the University of Delaware, where he is the school’s all time leader in goals, assists and points. -

Major League Soccer As a Case Study in Complexity Theory

Florida State University Law Review Volume 44 Issue 2 Winter 2017 Article 1 Winter 2017 Major League Soccer as a Case Study in Complexity Theory Steven A. Bank UCLA School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Contracts Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Other Law Commons Recommended Citation Steven A. Bank, Major League Soccer as a Case Study in Complexity Theory, 44 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 385 (2018) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol44/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MAJOR LEAGUE SOCCER AS A CASE STUDY IN COMPLEXITY THEORY STEVEN A. BANK* ABSTRACT Major League Soccer has long been criticized for its “Byzantine” roster rules and regu- lations, rivaled only by the Internal Revenue Code in its complexity. Is this criticism fair? By delving into complexity theory and the unique nature of the league, this Article argues that the traditional complaints may not apply in the context of the league’s roster rules. Effectively, critics are applying the standard used to evaluate the legal complexity found in rules such as statutes and regulations when the standard used to evaluate contractual complexity is more appropriate. Major League Soccer’s system of roster rules is the product of a contractual and organizational arrangement among the investor-operators. -

Jan12it Is Superdraft Morning Feel the Excitement? the Hum Yeah This Chart Is Shaping up to Be an Interesting Ride Tomorrow

Jan12It is SuperDraft morning Feel the excitement? The hum Yeah this chart is shaping up to be an interesting ride tomorrow. Teams are within Baltimore as we talk getting geared up as this thing.This want be my final jeer chart as this SuperDraft. Today I?¡¥m going board and will be doing a two round version,nfl jersey wholesale. I know I?¡¥ve done now four of these things barely its something I enjoy a lot during the off season. It may be over kill aboard my part to do as much as I do merely with each passing week current information comes out alternatively I chat to alter folks approximately the alliance that aid form my opinions here so changes must be made.I?¡¥ve had a lot of fun this year with this chart probably as its allowed me to help out aboard other venues favor SBnation.com and more recently aboard FCDallas.com. I try my best what can I say,football jersey maker.Below is my two circular ridicule draft I?¡¥ll have adding comments under as I think there longing be some trades that jolt this plenary thing up. Should any colossal trade come down within the morning I?¡¥ll dispute it and what it longing mean as the blueprint at that point. For now the order is where it?¡¥s been by as a pair weeks immediately so as contentions sake, nothing is changing and this is how I see it playing out tomorrow.2011 WVH Mock Draft(* = Generation adidas)1. Vancouver Whitecaps ??Perry Kitchen*, M, AkronA present leader within the house is Kitchen. -

Ezana Kahsay Daniel Strachan Ben Lundt Marcel Zajac David Egbo

Ben Lundt Ezana Kahsay David Egbo Skye Harter Daniel Strachan Marcel Zajac www.adidas.com TABLE OF CONTENTS TEAM INFORMATION MEET THE 2018 AKRON ZIPS MEDIA GUIDE 2018 Table of Contents ............................................................................................. 1 Meet the Zips ....................................................................................... 20-30 Quick Facts ...................................................................................................2 Directions to Campus ....................................................................................... 3 THIS IS AKRON SOCCER Athletics Communications ............................................................................... 3 This is Akron Soccer ............................................................................. 32-35 Quick Facts ....................................................................................................... 4 MLS Draft History ................................................................................. 36-38 2018 Schedule ................................................................................................. 5 Zips In The Pros ..........................................................................................39 Series Records vs. 2018 Opponents .............................................................6-7 Zips by Class ..............................................................................................40 Roster Information ..........................................................................................