QSC00-013.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RETAIL and COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY CITY of WAGGA WAGGA

ADVISORY REPORT ~ RETAIL and COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY CITY of WAGGA WAGGA Prepared For: WAGGA WAGGA CITY COUNCIL Prepared By: LEYSHON CONSULTING PTY LTD SUITE 1106 LEVEL 11 109 PITT STREET SYDNEY NSW 2000 TELEPHONE (02) 9224- 6111 FACSIMILE (02) 9224-6150 REP0615 APRIL 2007 © Leyshon Consulting Pty Ltd 2007 Leyshon Consulting TABLE of CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY........................................i-iv 1 INTRODUCTION............................................. 1 1.1 Background..............................................1 1.2 Study Tasks..............................................1 1.3 Definitions...............................................3 2 EXISTING CENTRES .......................................... 5 2.1 Introduction..............................................5 2.2 Wagga Wagga CBD........................................6 2.3 CBD North. .............................................8 2.4 Suburban Centres. ........................................9 2.4.1 Kooringal..........................................9 2.4.2 Southcity..........................................9 2.4.3 Lake Albert. ......................................1 0 2.4.4 Tolland. .........................................1 0 2.4.5 Turvey Tops.......................................1 0 2.4.6 Ashmont.........................................1 1 2.5 Bulky Goods. ...........................................1 1 2.6 Approved Development. ..................................1 2 3 DEMAND ANALYSIS ......................................... 1 3 3.1 Introduction.............................................1 -

Commerce Ballarat News Bulletin 12 – 18 February Quote of the Week

Commerce Ballarat News Bulletin 12 – 18 February Quote of the week: “Winning is about heart, not just legs. It’s got to be in the right place" Lance Armstrong Regional Industry Link Workshops BRACE, 602 Urquhart St, Ballarat Thursday 24 February 1 pm – 3 pm Members Free Non-members $25 Want to know how you can access new business opportunities? Register now to attend one of our ‘Regional Industry Link’ workshops and find out how to make the most of this free program that will match your business to relevant supply opportunities across Victoria. "Mind the Gap: Why EVERY generation just doesn’t get it” Alexandria on Lydiard 30 Lydiard St Nth, Ballarat Wednesday 9 March 12.00noon Members $42pp Non-members $50pp Panel discussion about the generation gap, age differences and how to overcome these issues in the workplace. Representing Gen Y: Jessica Saad, Angel Recruitment and Consultancy, and Melissa Abu-Gazaleh, Top Blokes Foundation. Representing Gen X: Glen Walker, Maxitrans, and Jeff Pulford, City of Ballarat. Facilitated by John Fitzgibbon General Manager 3BA & Power/FM. B.L.E.N.D Beaumont Tiles 106 Creswick Road, Ballarat Wednesday 9 March 5.30pm – 7.30pm Members Free Non-members $16.50 Guest speakers: Melissa Abu-Gazaleh, Top Blokes Foundation, and Jessica Saad, Angel Recruitment and Consultancy. Are you 39 and under and looking for an opportunity to share ideas and impressions of today’s business world? Drinks and savouries provided. Commerce Ballarat Race Day Ballarat Turf Club Thursday 14 April $55pp or $550 for a table of ten All those who have attended our race days know this is the fun way to do business. -

Annual Report 2012 67 Stores in Prime Locations

ANNUAL REPORT 2012 67 STORES IN PRIME LOCATIONS FIRST CHOICE for fashion, cosmetics and the home CONTENTS About Myer • 02 2012 Financial Results • 04 From the Chairman • 06 From the CEO • 08 Review of Operations • 10 Sustainability • 18 Board of Directors • 22 Management Team • 24 Corporate Governance Statement • 26 Directors’ Report • 39 Remuneration Report • 44 Financial Report • 60 Auditor’s Report • 112 Shareholder Information • 115 Corporate Directory Inside back cover MYER A MYER NN U AL R EPORT 2012 EPORT Annual General Meeting The 2012 Annual General Meeting of Myer Holdings Limited will be held at Mural Hall, Level 6, Myer Melbourne, / Bourke Street Mall, Melbourne, Victoria on Friday, 7 December 2012 at 11am. 01 Myer Holdings Limited ABN 14 119 085 602 Our vertically-integrated Myer Exclusive Brand model ABOUT MYER of managing the design, development and sourcing of wanted brands provides us with significant control and flexibility. This model, together with our two sourcing Myer is Australia’s largest department store offices in Asia, our world-class supply chain, and group, synonymous with style and fashion updated IT and merchandise systems, delivers speed to market, and effective inventory control, and gives us a for over 100 years. key competitive advantage. We also seek to acquire wanted brands where it makes commercial sense and where the addition of the brand Our focus on providing inspiration to everyone includes will further strengthen our merchandise offer. our customers, our 12,500 team members, our 54,000 shareholders, our 1,200 suppliers globally and the many Improve customer service and efficiency communities that we engage with our strong brand. -

Sidney Myer Fund the Myer Foundation Annual Report 2018–19

Sidney Myer Fund The Myer Foundation Annual Report 2018–19 Contents Mission 3 How to Read this Report 4 Joint Statement 5 Sidney Myer Fund Trustees 6 The Myer Foundation Directors 7 Strategic Theme: People 8 Strategic Theme: Organisations 10 Strategic Theme: Beyond Grantmaking 12 Strategic Theme: Family Engagement 14 Grant Listings 16 Summary Financial Information 23 L2R’s Due West 1 2 The Sidney Myer Fund and The Myer Foundation are two separate philanthropic entities of Myer family philanthropy. They are both managed by the same team and have separate but complementary philanthropic programs and activities. Sidney Myer, a generous philanthropist in his lifetime, left a portion of his estate upon his death in 1934 to be invested for the benefit of the community in which he made his fortune. That act created the Sidney Myer Fund which will exist in perpetuity. The income of the Fund is distributed annually. The Myer Foundation was established in 1959 by Sidney Myer’s sons, the late Kenneth Myer AC DSC, and Baillieu Myer AC, as a way to support initiatives and new opportunities arising from contemporary issues. The Myer Foundation was endowed through Kenneth Myer’s estate following his death in 1992. The Sidney Myer Fund and The Myer Foundation continue the legacy of Myer family generosity, through members of four succeeding generations of the Myer family, who give in many ways, to make significant and lasting contributions to our society. 3 How to Read this Report The FY19 Annual Report is organised Each pillar of the strategy features in a double page spread in this report. -

New Myer Store for Darwin

ASX & Media Release Tuesday 26 June 2012 New Myer store for Darwin Myer Holdings Limited (MYR) today announced plans to build a new store in Darwin, Northern Territory. The new Myer Darwin will be a two-level 12,000 square metre store featuring a large range of apparel, cosmetics, homewares and electrical merchandise. Myer Chief Executive Officer, Bernie Brookes, said that the new store would be the first full-line department store in Darwin and delivered an opportunity for Myer to reach a significant growth area and a new customer base in the north of Australia. “As we optimise our store network across the country, Darwin is the ideal location for a new store, and will expand our customer base and footprint into the Northern Territory for the first time. Darwin is a region of significant economic growth and the community support for the addition of a Myer store has been tremendous,” Mr Brookes said. “The store will be in an ideal location for us. Casuarina Square is already a well-established centre that has a strong customer offer including specialty retail, supermarkets, discount department stores and a cinema. We believe the addition of a full-line Myer store will further strengthen the customer proposition. “We are delighted to have reached an agreement with GPT Group to be a part of their proposed expansion of the Casuarina Square Shopping Centre. We also welcome the Territory Government's willingness to work towards integrating public transport into the development. “As we build on the success of our new Mackay store in Queensland, we are looking forward to the opening of our next two new stores at Fountain Gate (Victoria) in September and Townsville (Queensland) in October this year. -

Information About Coles Group

6 Information about Coles Group 6.1 Background Information Coles Group (ASX:CGJ) is one of Australia’s largest retailers with approximately 3,000 stores, revenue of $34.7 billion (FY2007) and market capitalisation of approximately $18.0 billion as at 25 September 2007. Coles Group is headquartered in Melbourne, Australia and employs approximately 170,000 people nationally. A brief history of Coles Group is set out below. • The fi rst Coles Group variety store was opened in Melbourne, Victoria in 1914 and the fi rst Coles Group supermarket was opened in 1960. At the end of the 2007 fi nancial year, 674 Coles and 71 Bi-Lo supermarkets were open. • The fi rst Kmart opened in Melbourne, Victoria in 1969, and as at the end of the 2007 fi nancial year, there were 182 Kmart stores in Australia and New Zealand, making it Australia’s largest discount department store operator. • In 1985, Coles Group merged with The Myer Emporium Limited to create Coles Myer Limited. • The merger with the Myer Emporium brought Target into the brand portfolio which, as at the end of the 2007 fi nancial year, had 268 locations in metropolitan and country areas offering on-trend apparel and soft home-wares. • Through the 1980s and 1990s Coles Group acquired a number of liquor businesses and over the past six years it has continued to expand its liquor business by acquiring hotels and rolling out superstores. • In 1994 the fi rst Offi ceworks store opened, with the chain having grown to 107 stores and nine Harris Technology Business Centres as at the end of the 2007 fi nancial year. -

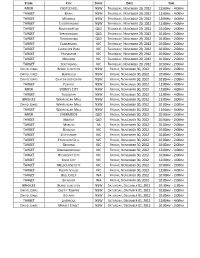

Myer Castle Hill 12:00Pm

STORE CITY STATE DATE TIME MYER CASTLE HILL NSW THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 29, 2012 12:00PM - 4:00PM TARGET ERINA NSW THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 29, 2012 12:00PM - 4:00PM TARGET MIRANDA NSW THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 29, 2012 12:00PM - 4:00PM TARGET TUGGERANONG NSW THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 29, 2012 12:00PM - 4:00PM TARGET ROCKHAMPTON QLD THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 29, 2012 10:00AM - 2:00PM TARGET SPRINGWOOD QLD THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 29, 2012 10:00AM - 2:00PM TARGET TOOWOOMBA QLD THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 29, 2012 10:00AM - 2:00PM TARGET CAMBERWELL VIC THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 29, 2012 10:00AM - 2:00PM TARGET CHIRNSIDE PARK VIC THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 29, 2012 10:00AM - 2:00PM TARGET FRANKSTON VIC THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 29, 2012 10:00AM - 2:00PM TARGET MALVERN VIC THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 29, 2012 10:00AM - 2:00PM TARGET SOUTHLAND VIC THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 29, 2012 10:00AM - 2:00PM DAVID JONES BONDI JUNCTION NSW FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 2012 10:00AM - 2:00PM DAVID JONES BURWOOD NSW FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 2012 10:00AM - 2:00PM DAVID JONES CHATSWOOD CHASE NSW FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 2012 10:00AM - 2:00PM TARGET PENRITH NSW FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 2012 12:00PM - 4:00PM MYER SYDNEY CITY NSW FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 2012 12:00PM - 4:00PM TARGET TUGGERAH NSW FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 2012 12:00PM - 4:00PM BING LEE WARRINGAH MALL NSW FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 2012 11:00AM - 3:00PM DAVID JONES WARRINGAH MALL NSW FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 2012 10:00AM - 2:00PM TARGET WARRINGAH MALL NSW FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 2012 11:00AM - 3:00PM MYER CHERMSIDE QLD FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 2012 10:00AM - 2:00PM TARGET MACKAY QLD FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 2012 10:00AM - 2:00PM -

Education for All. South East Asia and South Pacific Sub-Regional

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 332 852 RC 018 161 AUTHOR Devlin, Brian C., Ed. TITLE Education for All. South East Asia andSouth Pacific Si:lip-Regional Conference Report (Darwin,Northern Territory, Australia, October 14-19, 1990). INSTITUTION Northern Territory Dept. of Education,Darwin (Australia). SPONS AGENCY Australian Dept. of Employment, Educationand Training, Canberra.; Australian International Development Assistance Bureau.; International Literacy Year Secretariat, Canberra (Australia).; United Nations Educational, Scientificand Cultural Organization, Bangkok (Thailand). PrincipalRegional Office for Asia and the Pacific. REPORT NO ISBN-0-7245-2500-9 PUB DATE 91 NOTE 232p. PUB TYPE Collected Works - Conference Proceedings(021) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Access to Education; Adult Education;Bilingual Education; *Disabilities; Education Work Relationship; Elementary SecondaryEducation; Equal Education; Foreign Countries; *Indigenous Populations; *Literacy Education; Multicultural Education; Poverty; *Rural Education;Teacher Education; *Womens Education IDENTIFIERS *Asia (Southeast); Australia; PacificIslands; *South Pacific ABSTRACT In October 1990, 223 delegates from 22nations of Southeast Asia and the South Pacific metin Australia to discuss plans and strategies for achieving universaleducation in the region. To inform planning and action, theconference defined fivegroups of people for whom universal education isa priority: indigenous people and minorities, people in poverty,people in remote areas,people with disabilities, -

2020 Annual Report

24 September 2020 The Manager Company Announcements Office Australian Securities Exchange Dear Manager, 2020 ANNUAL REPORT In accordance with the ASX Listing Rules, attached for release to the market is Coles Group Limited’s 2020 Annual Report. This announcement is authorised by the Board. Yours faithfully, Daniella Pereira Company Secretary For more information: Investor Relations Media Mark Howell Meg Rayner Mobile: +61 400 332 640 Mobile: +61 439 518 456 E-mail: E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Coles Group Limited ABN 11 004 089 936 800 Toorak Road Hawthorn East Victoria 3123 Australia PO Box 2000 Glen Iris Victoria 3146 Australia Telephone +61 3 9829 5111 www.colesgroup.com.au 2020 Annual Report Sustainably feed all Australians to help them lead healthier, happier lives Coles Group Limited ABN 11 004 089 936 Coles Group Limited 2020 Annual Report Coles acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of Country throughout Australia and pays its respects to elders past and present. We recognise their rich cultures and continuing connection to land and waters. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are advised that this document may contain names and images of people who are deceased. All references to Indigenous people in this document are intended to include Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people. DRAFT 21 COL1634_An- nualReport_d31a – Rnd 16 Copy September23, 2020 7:52 PM Forward-looking statements This report contains forward-looking statements in relation to Coles Group Limited (‘the Company’) and its controlled entities (together ‘Coles’ or ‘the Group’), including statements regarding the Group’s intent, belief, goals, objectives, initiatives, commitments or current expectations with respect to the Group’s business and operations, market conditions, results of operations and financial conditions, and risk management practices. -

2019 Annual Report. Sustainably Feed All Australians to Help Them Lead Healthier, Happier Lives

2019 Annual Report. Sustainably feed all Australians to help them lead healthier, happier lives. Coles Group Ltd / Annual Report & Financial Statements 2019 Coles Group Limited 2019 Annual Report1 1 Coles acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of Country throughout Australia and pays its respects to elders past and present. We recognise their rich 1914. 1914 cultures and continuing connection to land and waters. The first Coles variety store opens in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are Collingwood, Victoria, advised that this document may contain names and founded by George James Coles and his images of people who are deceased. 1924 brother Jim. Coles’ first city store All references to Indigenous people in this document opens in Bourke Street, Melbourne. are intended to include Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people. 1939-1945 During World War II, women manage the stores as 90% of male Contents team members enlist 1956 to fight. The first self-service store opens in February. 3 Welcome to Coles 4 2019 performance 1960 5 2019 highlights The first Coles 6 Message from the Chairman supermarket opens 8 Managing Director and in North Balwyn, Victoria. 1980s Chief Executive Ocer’s report Coles acquires a number 12 Our vision, purpose and strategy of liquor businesses, 14 How we create value including the Liquorland and Vintage Cellars 17 Sustainability overview 1985 brands. 18 Sustainability highlights Coles merges with The Myer Emporium 20 Our financial and operating performance Limited to create 29 Looking to the future Coles Myer Limited. 30 How we manage risk 1999 35 Climate change Online shopping is first 38 Corporate governance 2003 trialled by Coles in 23 Melbourne postcodes, 45 Directors’ report Coles enters into an Alliance Agreement paving the way for the 63 Financial report with Shell whereby current Coles Online 104 Shareholder information Coles operates the oering. -

Interview with Bill Wavish, Executive Chairman of Myer 50 Days After Acquisition

INTERVIEW WITH BILL WAVISH, EXECUTIVE CHAIRMAN OF MYER 50 DAYS AFTER ACQUISITION Q. Bill, what were the first things you and Bernie did upon arriving at Myer? A. I had had a over six months doing due diligence, then Bernie and I had two months to get ready between when the sale was announced and when we got the keys on June 2. Thus by Day One we had detailed strategies formulated with help from TPG Newbridge and Debenhams. Our Team was almost complete, comprising mainly retained Myer executives, together with a sprinkling of new talent. Our "Hundred Day Plan" was ready in great detail. We were able to hit the ground running. A clear focus was for us to develop a clear plan and vision and numbers to satisfy ourselves, TPG Newbridge, the Myer Family and our financiers, yet to remain flexible enough and listen enough to our remaining Myer executives, especially given our limited knowledge of fashion. We have tried to tread that path very carefully, and I believe that the Team understand and appreciate that. On Days 0 and 1, we took the Management Board of ten (2 had yet to join) to Mornington Peninsula to get to know each other, to talk strategy, and importantly to talk "Culture." At that time we told them that we appreciated that they had endured a long arduous and uncertain time during the due diligence period and the sales process by CML. Bernie and I said that we wanted each Management Board Member to fly business class to London for a week with their partner to look at Debenham's (and London) then to come back and further review strategy. -

'Shop-Top Living': the Past and Future of Launceston

Sustainable Heritage and ‘Shop-Top Living’: The Past and Future of Launceston Katrina L. Hill Masters of Planning University of Tasmania Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for Master of Planning University of Tasmania October 2017 Declaration I declare that all the material in this thesis contains no materials previously published or written by others except where there is clear acknowledgement or reference to the work of others and I have complied with and agreed to the University statement on Plagiarism and Academic Integrity on the University website at http://www.students.utas.edu.au/plagiarism/ Katrina L. Hill Date: 20 October 2017 pg. 2 Abstract “heritage led regeneration raises aspirations” HRH Prince Charles - Dumfries House, Britain’s Hidden Heritage (BBC One, 2011) A great city is vibrant and dynamic because of the people who live in it. For the city of Launceston, a restorative tonic can be found in a return to living ‘above the shop’ lost due to societal change and successive urban planning strategies designed to improve public health and safety outcomes. This research project demonstrates the complexity of ‘shop-top living’ and that all the internalities and externalities at work within the city have affected shops and shopping. Launceston is perfect for examining urban planning and design coupled with heritage revitalization and also government and private spending on significant development projects. The City of Launceston’s significant heritage values greatly impact enabling measures and implementation schemes for urban regeneration. An understanding of both the retail and urban planning history of Launceston provides the background to the problems and issues of today with restoring both the form and function that ‘shop-top living’ affords.