Sefton Metropolitan Borough Council Care Practice Diagnostic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Verification Requirements for Cover Systems YALPAG Technical Guidance for Developers, Landowners and Consultants Page | 1 Overview Flowchart

VERIFICATION REQUIREMENTS FOR COVER SYSTEMS Technical Guidance for Developers, Landowners and Consultants Yorkshire and Lincolnshire Pollution Advisory Group Version 4.1 – June 2021 The purpose of this guidance is to promote consistency and good practice for development on land affected by contamination. The Local Authorities in Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, the North East of England, East Anglia, Greater Manchester and St Helens who have adopted this guidance are shown below: Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 The Process of Verification .................................................................................................... 1 Overview Flowchart ................................................................................................................ 2 Key Points ............................................................................................................................... 3 KP1: Source of Material ...................................................................................................... 3 KP2: Characterisation of Material ...................................................................................... 3 KP3: Suitability of Material ................................................................................................. 5 KP5: Verification of Required Depth .................................................................................. 6 KP6: Reporting ................................................................................................................... -

Introduction Accessibility Across UK Local Authorities

Accessibility across UK Local Authorities Socitm and Sitemorse collaboration – supporting BetterConnected Introduction Digital accessibility regulation is challenging to manage and is negatively impacting those for whom the rules should be assisting. Public sector bodies must deal with accessibility, against a timetable. Now with a specific timeline in relation to the public sector achieving accessibility compliance for their websites, we have summarised our Q3 / 2019 results, reporting the position across the sector. For over 10 years Sitemorse have been in partnership with Socitm, working on numerous initiatives including BetterConnected. Sept. 29th 2019 | Ver. 1.9 | Release | © Sitemorse In Summary. For the Sitemorse 2019 Q3 UK Local Government INDEX we assessed over 400 authority websites for adherence to WCAG 2.1. The INDEX was compiled 37% following some 250 million tests, checks and measures across nearly 820,000 URLs. 17% Comparing the Q3 to the Q2 results; 49 improved, 44 dropped, with the balance remaining the same. Three Local Authorities achieved a score of 10 (out of 10) for accessibility. It’s important to note that the INDEX covers the main website of each authority. The law applies to all websites operated, directly or on behalf of the authority. 46% The target score is 7.7 out of 10. • Pages passing accessibility level A: 87.11% • Pages passing accessibility level AA: 12.2% • Of the 3,550 PDF’s 56.4% PDF’s passed the accessibility tests. Score 10 - 7 Score 5 - 6 Score 1 - 4 It is important to note that this score is for automated tests; there are still manual tests that need to be performed however, a score of 10 demonstrates a thorough understanding of what needs to be done and it is highly likely that the manual tests will pass too. -

Delivering Better Health and Care for Everyone

Delivering better health and care for everyone Summary of our Five Year Plan You can take a look back at some of the improvements West Yorkshire and Harrogate Health and Care Partnership has been making with local people to improve their lives in our short film here You can also find out more about the positive difference our Partnership is making online here Our Partnership We also want to say thank you to all the ^ Photo credit: Leeds Irish Health and Homes people who’ve shared their stories so far and given their views about health and Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) Harrogate and District NHS care in West Yorkshire and Harrogate. NHS Airedale, Wharfedale Foundation Trust and Craven CCG* Leeds Community Healthcare NHS Trust Watch our thank you film here NHS Bradford City CCG* Leeds and York Partnership NHS NHS Bradford Districts CCG* Foundation Trust NHS Calderdale CCG Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust NHS Greater Huddersfield CCG Locala Community Partnerships The Mid-Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust We are committed to honesty and NHS Harrogate and Rural District CCG transparency in all our work and NHS Leeds CCG South West Yorkshire Partnership NHS also producing this information in NHS North Kirklees CCG Foundation Trust Tees Esk and Wear Valleys NHS accessible formats. Our Five Year NHS Wakefield CCG Plan summary is available in: Foundation Trust Yorkshire Ambulance Service NHS Trust • Audio Local councils • EasyRead City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council Others involved • BSL Calderdale Council Healthwatch • Animated -

Transforming Care Partnership Plan

Transforming Care Partnership Plan Calderdale, Kirklees, Wakefield and Barnsley 1 What is the Calderdale, Kirklees, Wakefield and Barnsley Transforming Care Partnership? This group has been started to work on making care and services better for people with a learning disability in the Calderdale, Kirklees, Wakefield and Barnsley areas. We are making plans on how to do this work. When the work starts, we will have a board of people that will check and make sure our plans are happening. Who is on the board? Kirklees Council Calderdale Council Wakefield Council Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council Calderdale Clinical Commissioning Group Greater Huddersfield Commissioning Group Transforming Care North Kirklees Clinical Commissioning Group Partnership Wakefield Clinical Commissioning Group Barnsley Clinical Commissioning Group Specialist Commissioning Services Learning Disability Partnership Boards. 2 What isWhat the Calderdale, is the Calderdale, Kirklees, Wakefield Kirklees, and BarnsleyWakefield Transforming and Care Barnsley Partnership (CKWB) Plan about? Transforming Care Partnership Plan about? We are working on a plan to change care for people with a learning disability and/or autism in our areas. There are 2 national plans called: Building the Right Support National Service Model October 2015. National plans are plans for the whole of England. We will make our plan fit in with the National plans. Each area in Calderdale, Kirklees, Wakefield and Barnsley will use the plan to work on their own local services. Our Partnership will check how the areas are doing. It will help to share good information across the areas to make sure we are all working in the best way. 3 Who is the plan for? The plan is for everyone in the community but we want to make sure it is good for people who: Have a mental health illness. -

Street Lighting As an Asset; Smart Cities and Infrastructure Developments ADEPTE ASSOCIATION of DIRECTORS of ENVIRONMENT, ECONOMY PLANNING and TRANSPORT

ADEPTE ASSOCIATION OF DIRECTORS OF ENVIRONMENT, ECONOMY PLANNING AND TRANSPORT DAVE JOHNSON ADEPT Street Lighting Group chair ADEPT Engineering Board member UKLB member TfL Contracts Development Manager ADEPTE ASSOCIATION OF DIRECTORS OF ENVIRONMENT, ECONOMY PLANNING AND TRANSPORT • Financial impact of converting to LED • Use of Central Management Systems to profile lighting levels • Street Lighting as an Asset; Smart Cities and Infrastructure Developments ADEPTE ASSOCIATION OF DIRECTORS OF ENVIRONMENT, ECONOMY PLANNING AND TRANSPORT ASSOCIATION OF DIRECTORS OF ENVIRONMENT, ECONOMY, PLANNING AND TRANSPORT Representing directors from county, unitary and metropolitan authorities, & Local Enterprise Partnerships. Maximising sustainable community growth across the UK. Delivering projects to unlock economic success and create resilient communities, economies and infrastructure. http://www.adeptnet.org.uk ADEPTE SOCIETY OF CHIEF OFFICERS OF CSS Wales TRANSPORTATION IN SCOTLAND ASSOCIATION OF DIRECTORS OF ENVIRONMENT, ECONOMY PLANNING AND TRANSPORT ADEPTE SOCIETY OF CHIEF OFFICERS OF CSS Wales TRANSPORTATION IN SCOTLAND ASSOCIATION OF DIRECTORS OF ENVIRONMENT, ECONOMY PLANNING AND TRANSPORT Bedford Borough Council Gloucestershire County Council Peterborough City Council Blackburn with Darwen Council Hampshire County Council Plymouth County Council Bournemouth Borough Council Hertfordshire County Council Portsmouth City Council Bristol City Council Hull City Council Solihull MBC Buckinghamshire County Council Kent County Council Somerset County -

YALPAG Verification Guidance on Requirements for Cover System

VERIFICATION REQUIREMENTS FOR COVER SYSTEMS Technical Guidance for Developers, Landowners and Consultants Yorkshire and Lincolnshire Pollution Advisory Group Version 4.1 – June 2021 The purpose of this guidance is to promote consistency and good practice for development on land affected by contamination. The Local Authorities in Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, the North East of England, East Anglia, Greater Manchester and St Helens who have adopted this guidance are shown below: Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 The Process of Verification .................................................................................................... 1 Overview Flowchart ................................................................................................................ 2 Key Points ............................................................................................................................... 3 KP1: Source of Material ...................................................................................................... 3 KP2: Characterisation of Material ...................................................................................... 3 KP3: Suitability of Material ................................................................................................. 5 KP5: Verification of Required Depth .................................................................................. 6 KP6: Reporting ................................................................................................................... -

Annex A: List of Respondents

Annex A: List of Respondents We received a total of 185 responses to the consultation. The list below provides details of the organisations that responded to the consultation. Affinity Water AGMA Albion Water Anglian Central Regional Flood and Coastal Committee Anglian Water Anglian Water Services Ashford Borough Council Association of Drainage Authorities Aylesbury Vale District Council Basingstoke and Deane Borough Council Bath & North East Somerset Council Bedford Borough Council Birmingham City Council Blackburn with Darwen Borough council Blackpool Council Bracknell Forest Council Bristol City Council Bristol Water Broadland District Council Bromsgrove District Council Buckinghamshire County Council Cambridgeshire County Council Campaign to Protect Rural England Canal and River Trust Central Bedfordshire Council Chartered Institution of Water and Environmental Management Chelmsford City Council City of London Corporation CLA Clear Environmental Colchester Borough Council Cornwall Council Coventry City Council Croudace Homes.co.uk Croydon Council Dartford Borough Council DEE VALLEY WATER Derbyshire County Council Derbyshire Dales District Council Devon County Council District Council's Network Dorset County Council Dudley Metropolitan Borough Council Dwr Cymru Welsh Water East of England Local Government Association East Riding of Yorkshire council East Sussex County Council EcoFutures Ltd. Enfield Council Environment Agency Environmental Services Association Epping Forest District Council Essex Chambers of Commerce Essex County Council -

List of Town Team Partners

List of Town Team Partners Name of local authority (who will act as Accountable Body Name of Town Team for the grant Lancing Town Team Partnership Adur District Council Wigton Town Team Allerdale Borough Council Love Maryport Town Team Allerdale District Council Heanor Town Team Amber Valley Borough Council Bognor Regis "Heart of the Town" Team Arun District Council Littlehampton Town Team Arun District Council Idlewells Shopping Centre, Sutton-in-Ashfield Ashfield District Council Kirkby Town Team Ashfield District Council Aylesbury Town Centre Partnership Aylesbury Vale District Council Sudbury (Suffolk) Town Team Babergh District Council Barnsley Town Team Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council Wombwell Community Board (Wombwell Town) Barnsley Metropolitan Council Barrow-in-Furness Barrow Borough Council Dalton with Newton Town Council Barrow Borough Council Radstock Town Team Bath and North East Somerset Innovation Boldmere Birmingham City Council Kings Heath Centre Partnership Birmingham City Council Saltley Business Association Birmingham City Council Soho Road Town Centre Partnership Birmingham City Council Sparbrook and Springfield Town Centres Birmingham City Council Erdington Town Centre Partnership Birmingham City Council Lifford Business Association Birmingham City Council Retail Birmingham Birmingham City Council Borough Council of Wellingborough Town Team Wellingborough Poole Town Centre Partnership Borough of Poole Boston BID Boston Borough Council Boscombe Regeneration Partnership Bournemouth Borough Council Halstead Town -

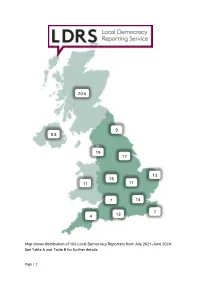

Page | 1 Map Shows Distribution of 165 Local Democracy Reporters

20.5 9 5.5 19 17 13 15 11 11 7 13 7 4 13 Map shows distribution of 165 Local Democracy Reporters from July 2021-June 2024. See Table A and Table B for further details Page | 1 Table A: Allocated contracts and reporters by operating company Company name Contracts Reporters Archant 1 2 Brighton and Hove News 1 1 Caerphilly Media 1 1 Citizen News & Media 1 1 DC Thomson 5 3.5 Iliffe Media Publishing 1 1 JPI Media 24 35.5 KM Media Group 1 3 London Evening Standard 1 1 Newbury News & Media 1 1 Newsquest 23 28.5 Notts TV 1 3 Radio Exe 1 3 Radio Manx 1 1 Reach 51 75 Shetland News 1 0.5 Social Spider CIC 2 2 Stonebow Media 1 2 TOTAL 118 165 Page | 2 Table B: Allocated contracts and reporters by BBC Nation and Region Contract BBC Region Contracts Reporters holders East 9 13 See page 4 East Midlands 4 11 See page 5 North East 5 9 See page 6 North West 14 19 See page 7 South 9 13 See page 8 South East 3 7 See page 8 South West 2 4 See page 9 West 5 7 See page 9 West Midlands 7 15 See page 10 Yorkshire & Lincs 9 17 See page 11 London 12 13 See page 12-13 Northern Ireland 11 5.5 See page 14 Scotland 17 20.5 See page 15-16 Wales 11 11 See page 17 TOTAL 118 165 Page | 3 East Contract Number Local authorities assigned to Contract holder number of LDRs contract E01 1 Cambridgeshire and JPI Media Peterborough Metro Mayor Peterborough City Council E02 1 Cambridgeshire County Council Reach E03 1 Buckinghamshire Council Newsquest Milton Keynes Council E04 2 Bedford Borough Council JPI Media Central Bedfordshire Council Luton Borough Council E05 2 Hertfordshire -

Gold Awards for Address and Street Data 2013

Gold Awards for Address and Street Data 2013 Gold Award for Address Data Adur & Worthing Councils Pembrokeshire County Council Allerdale District Council Peterborough City Council Blaenau Gwent County Borough Poole Borough Council Council Reigate & Banstead Borough Council Bournemouth Borough Council Runnymede Borough Council Bridgend County Borough Council Rushmoor Borough Council Brighton and Hove City Council Scarborough Borough Council Broxbourne Borough Council Sheffield City Council Caerphilly County Borough Council South Gloucestershire Council Calderdale Council South Holland District Council Carlisle City Council South Northamptonshire Council Conwy County Borough Council South Tyneside Council Dartford Borough Council Spelthorne Borough Council Denbighshire County Council St Albans City & District Council Derbyshire Dales District Council St Edmundsbury Borough Council Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Stafford Borough Council Council Stockton-On-Tees Borough Council East Devon District Council Stratford-On-Avon District Council East Northamptonshire Council Stroud District Council East Riding Of Yorkshire Council Surrey Heath Borough Council Eastleigh Borough Council Swale Borough Council Enfield Council Tamworth Borough Council Epsom and Ewell Borough Council Tonbridge and Malling Borough Flintshire County Council Council Forest Heath District Council Torfaen County Borough Council Hartlepool Borough Council Torridge District Council Herefordshire Council Vale of Glamorgan Council Huntingdonshire District Council Vale of White -

Public Sector Exit Payments: Response to the Consultation

Public Sector Exit Payments: response to the consultation Sept 2015 Public Sector Exit Payments: response to the consultation Sept 2015 © Crown copyright 2015 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] ISBN 978-1-910835-56-2 PU1852 Contents Chapter 1 Summary 3 Chapter 2 Outline of government proposals 5 Chapter 3 Introduction 7 Chapter 4 An exit payment cap in the public sector 9 Annex A List of respondents 15 1 Summary 1 1.1 The government announced on 23 May 2015 that it intended to end six-figure exit payments for public sector workers. 1.2 On 31 July 2015 the government published a consultation document asking for respondents’ views on the details of the policy. The consultation closed on 27 August 2015. 1.3 The core elements of the proposal were to: Apply a £95,000 cap on the total value of exit payments made to employees in the public sector Apply the cap to all forms of exit payment, including cash lump sums, early access to an unreduced pension, payments in lieu of notice and non-financial and other benefits Apply the cap to all types of arrangements for determining exit payments Establish a waiver process for exceptional circumstances Apply the policy to all public sector bodies, with a small number of bodies granted an exemption from the policy 1.4 The consultation document can be seen on Gov.uk: 1.5 Over 4,000 responses to the consultation were received. -

Joint Arrangements

Joint Arrangements SECTION 4 - JOINT ARRANGEMENTS The following are arrangements to jointly discharge functions, in accordance with Section 101(5) of the Local Government Act 1972 and Section 9EB of the Local Government Act 2000. Leeds City Region Business Rates Pool Joint Committee Aims: to operate the Leeds City Region Business Rates Pool and to further economic development activities within the region. Member Authorities: City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council, Calderdale Council, Harrogate Borough Council, Kirklees Council, Leeds City Council, Wakefield Metropolitan District Council, City of York Council. Leeds City Council Membership: the Leader Full membership details, terms of reference, functions and rules governing the conduct and proceedings of meetings can be found at: http://www.leeds.gov.uk/council/Pages/Leeds-City-Region-business-rates-pool.aspx West Yorkshire Joint Services Committee Functions: The discharge of functions with regard to archives and archaeology, grants to voluntary bodies and trading standards and related matters Member Authorities : City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council, Calderdale Council, Kirklees Metropolitan Council, Leeds City Council, City of Wakefield Metropolitan District Council. Leeds City Council Membership: 4 Members1 Full membership details, Terms of Reference, functions and rules governing the conduct and proceedings of meetings can be found at : http://www.wyjs.org.uk/about-us/publication-scheme/ 1 Of whom at least one shall be an Executive Member (Regulation 12 of the Local